An Inspection of the Work of Border Force, Immigration Enforcement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bloomsbury Professional

Immigration Asylum 24_2 cover.qxp:Layout 1 16/6/10 09:42 Page 1 Related Titles from Bloomsbury Professional JOURNAL of Immigration Law and Practice, 4th edition 24 Number 2 2010 Journal of Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Law Volume IMMIGRATION By David Jackson, George Warr, Julia Onslow-Cole & Joseph Middleton Reverting to hardback format, the fourth edition of this clear and practical book has been thoroughly updated by a team of specialist practitioners. It deals comprehensively with ASYLUM AND immigration law procedure and practice, covering European and human rights law, deportation, asylum and onward appeals. In this continually evolving area of law, this fourth edition takes into account all recent NATIONALITY major legislation changes and developments, relevant case law and policies since the last edition. ISBN: 978 1 84592 318 1 Price: £120 Format: Hardback LAW Pub date: Dec 2008 Asylum Law and Practice, 2nd edition Volume 24 Number 2 2010 Pages 113–224 By Mark Symes and Peter Jorro Written by two of the leading authorities on the law relating to asylum, Asylum Law and EDITORIAL Practice, 2nd edition is a detailed exposition of the law relating to asylum and NEWS international protection. ARTICLES Bringing together in one volume, all relevant aspects of asylum law and practice in the The Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009 United Kingdom, this book is comprehensive enough to serve as a reliable source of Alison Harvey information and analysis to all asylum practitioners. Its depth, thoroughness, and clarity make it a must have for all practitioners. Victims of Human Trafficking in Ireland – Caught in a Legal Quagmire The book is focused on the position in the UK, but with reference to refugee law cases in Hilkka Becker other jurisdictions; such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the USA. -

The Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 (Jersey) Order 2003

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2003 No. 1252 IMMIGRATION The Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 (Jersey) Order 2003 Made - - - - - 8th May 2003 Coming into force - - 5th June 2003 At the Court at Buckingham Palace, the 8th day of May 2003 Present, The Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty in Council Her Majesty, in exercise of the powers conferred upon Her by section 36 of the Immigration Act 1971(a) and section 170(7) of the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999(b), is pleased, by and with the advice of Her Privy Council, to order, and it is hereby ordered, as follows:— 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 (Jersey) Order 2003 and shall come into force on 5th June 2003. (2) In this Order— “the 1971 Act” means the Immigration Act 1971, and “Jersey” means the Bailiwick of Jersey. (3) For the purposes of construing provisions of the 1971 Act as part of the law of Jersey, any reference to an enactment which extends to Jersey shall be construed as a reference to that enactment as it has eVect in Jersey. 2. The provisions of the Immigration and Asylum Act 1999 which are specified in the left- hand column of the Schedule to this Order shall extend to Jersey subject to the modifications specified in relation to those provisions in the right-hand column of that Schedule, being such modifications as appear to Her Majesty to be appropriate. 3. The Immigration (Jersey) Order 1993(c) shall be varied as follows— (a) at the end of article 4(1), insert “and section 20(2) of the Interpretation Act 1978 shall apply for the interpretation of this Order as it applies for the interpretation of an Act of Parliament.”; (b) for the modification of “Committee” made by paragraph 18(a)(i) of Schedule 1 to that Order, substitute— ““Committee” means the Home AVairs Committee of the States”. -

Background Introduction Effectiveness of Home Office Communications to Its Partners, Responders and the Wider Public About Its P

(COR0040) Written evidence submitted by the Immigration Law Practitioners’ Association (COR0040) Background 1. ILPA is a professional association founded in 1984, the majority of whose members are barristers, solicitors and advocates practising in all aspects of immigration, asylum and nationality law. Academics, non-governmental organisations and individuals with a substantial interest in the law are also members. ILPA exists to promote and improve advice and representation in immigration, asylum and nationality law, to act as an information and knowledge resource for members of the immigration law profession and to help ensure a fair and human rights-based immigration and asylum system. ILPA is represented on numerous government, official and non-governmental advisory groups and regularly provides evidence to parliamentary and official enquiries. Introduction 2. This note collates evidence and perspectives from ILPA members. ILPA has previously submitted a series of policy recommendations to the Home Office, and these were sent to the Committee on 22 March 2020 (Appendix 1). We have focussed our submission on Home Office communications, as well as looking at some of the policy responses to date. Effectiveness of Home Office communications to its partners, responders and the wider public about its preparations 3. The overwhelming theme of the responses from ILPA members has been that the Home Office public communication on these issues has been lacking. In addition, what guidance there is should be publicly accessible and easy to find, this has unfortunately not been the case so far 4. We have set out below a chronology of the Home Office communications and response to the pandemic. -

Departmental Overview Home Office 2019

A picture of the National Audit Office logo DEPARTMENTAL OVERVIEW 2019 HOME OFFICE FEBRUARY 2020 If you are reading this document with a screen reader you may wish to use the bookmarks option to navigate through the parts. If you require any of the graphics in another format, we can provide this on request. Please email us at www.nao.org.uk/contact-us HOME OFFICE This overview summarises the work of the Home Office including what it does, how much it spends, recent and planned changes, and what to look out for across its main business areas and services. Bookmarks and Contents Overview. CONTENTS About the Department. How the Department is structured. Where the Department spends its money. Key changes to Departmental expenditure. Major programmes and projects. OVERVIEW Exiting the European Union. PART [03] page – About the Department PART [01] 3 – Dealing with challenges in the border, Part [01] – The pressures on police. page – The pressures on police page – How the Department is structured 12 18 immigration and citizenship system Part [02] – The changing nature of crime. – Where the Department spends its money Part [03] – Dealing with challenges in the border, immigration and citizenship system. Dealing with challenges in the border, immigration– Key and changescitizenship system to continued Departmental expenditure Part [04] – Challenges in managing contracts–. Major programmes and projects Challenges in managing contracts continued PART [02] PART [04] – Exiting the European Union page14 – The changing nature of crime page 20 – Challenges in managing contracts The National Audit Office (NAO) helps Parliament hold government to account for the way it If you would like to know more about the NAO’s work on the Home Office, please contact: If you are interested in the NAO’s work and support for spends public money. -

Information About Becoming a Special Constable

Citizens in Policing #DCpoliceVolunteers Information about becoming a Special Constable If you would like to gain invaluable experience and support Devon & Cornwall Police in making your area safer join us as a Special Constable Contents Page Welcome 4 Benefits of becoming a Special Constable 6 Are you eligible to join? 7 Example recruitment timeline 10 Training programme 11 Frequently asked questions 13 Information about becoming a Special Constable 3 Welcome Becoming a Special Constable (volunteer police officer) is your Becoming a volunteer Special Constable is a great way for you chance to give something back to your community. Everything to make a difference in your community, whilst at the same time you do will be centred on looking after the community, from developing your personal skills. Special Constables come from all businesses and residents to tourists, football supporters and walks of life but whatever your background, you will take pride from motorists. And you’ll be a vital and valued part of making Devon, giving something back to the community of Devon and Cornwall. Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly safer. We are keen to use the skills you can bring. In terms of a volunteering opportunity, there’s simply nothing We have expanded the roles that Special Constables can fulfil, with else like it. Special Constables work on the front line with regular posts for rural officers, roads policing officers and public order police officers as a visible reassuring presence. As a Special officers all coming on line. I am constantly humbled and inspired by Constable you will tackle a range of policing issues, whether that the commitment shown by Special Constables. -

The Uk's Privatised Migration Surveillance Regime

THE UK’S PRIVATISED MIGRATION SURVEILLANCE REGIME: A rough guide for civil society February 2021 privacyinternational.org THE UK’S PRIVATISED MIGRATION SURVEILLANCE REGIME: A rough guide for civil society ABOUT PRIVACY INTERNATIONAL Governments and corporations are using technology to exploit us. Their abuses of power threaten our freedoms and the very things that make us human. That’s why Privacy International campaigns for the progress we all deserve. We’re here to protect democracy, defend people’s dignity, and demand accountability from the powerful institutions who breach public trust. After all, privacy is precious to every one of us, whether you’re seeking asylum, fighting corruption, or searching for health advice. So, join our global movement today and fight for what really matters: our freedom to be human. Open access. Some rights reserved. Privacy International wants to encourage the circulation of its work as widely as possible while retaining the copyright. Privacy International has an open access policy which enables anyone to access its content online without charge. Anyone can download, save, perform or distribute this work in any format, including translation, without written permission.This is subject to the terms of the Creative Commons Licence Deed: Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivative Works 2.0 UK: England & Wales. Its main conditions are: • You are free to copy, distribute, display and perform the work; • You must give the original author (‘Privacy International’) credit; • You may not use this work for commercial purposes; • You are welcome to ask Privacy International for permission to use this work for purposes other than those covered by the licence. -

Home Office Appraisal Report 1953-2016

Appraisal Report HOME OFFICE 1953 - 2016 Home Office Appraisal report CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................... 4 BACKGROUND INFORMATION .................................................................................................. 6 1.2 Type of agency ............................................................................................................... 11 1.3 Annual budget ................................................................................................................. 11 1.4 Number of employees ..................................................................................................... 11 1.5 History of organisation .................................................................................................... 12 1.6 Functions, activities, and recordkeeping ......................................................................... 25 1.7 Name of the parent or sponsoring department) .............................................................. 30 1.8 Relationship with parent department .............................................................................. 30 1.9 Relationship with other organisations ............................................................................. 30 SELECTION DECISIONS ............................................................................................................ 32 2.1 Areas of Policy Work undertaken in the organisation .................................................... -

In the Supreme Court of Tennessee at Nashville

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF TENNESSEE AT NASHVILLE _______________________________________ ) DANIEL RENTERIA-VILLEGAS, ) DAVID ERNESTO GUTIERREZ- ) TURCIOS, and ROSA LANDAVERDE, ) ) Plaintiffs-Movants, ) ) v. ) M2011-02423-SC-R23-CQ ) METROPOLITAN GOVERNMENT OF ) Trial Court No. 3:11-cv-218 (M.D. Tenn.) NASHVILLE AND DAVIDSON COUNTY, ) and UNITED STATES IMMIGRATION ) AND CUSTOMS ENFORCEMENT, ) ) Defendants-Respondents. ) _______________________________________) PLAINTIFFS’ REPLY BRIEF ON CERTIFICATION FROM THE U.S. DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE Elliott Ozment Trina Realmuto R. Andrew Free NATIONAL IMMIGRATION PROJECT OF THE IMMIGRATION LAW OFFICES NATIONAL LAWYERS GUILD OF ELLIOTT OZMENT 14 Beacon Street, Suite 602 1214 Murfreesboro Pike Boston, MA 02108 Nashville, Tennessee 37217 William L. Harbison Thomas Fritzsche Phillip F. Cramer Daniel Werner SHERRARD & ROE, LLC Immigrant Justice Project 150 3rd Avenue S., Suite 1100 SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER Nashville, Tennessee 37201 233 Peachtree St. NE, Suite 2150 Atlanta, GA 30303 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................ ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......................................................................................................... iv I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 II. ARGUMENT ..................................................................................................................... -

Wales-And-Sw.Pdf

THE UK BORDER AGENCY RESPONSE TO THE CHIEF INSPECTOR’S REPORT ON OPERATIONS IN WALES AND THE SOUTH WEST OF ENGLAND THE UK BORDER AGENCY RESPONSE TO RECOMMENDATIONS FROM THE CHIEF INSPECTOR’S REPORT ON OPERATIONS IN WALES AND THE SOUTH WEST OF ENGLAND The UK Border Agency thanks the Independent Chief Inspector for this report, and for his comments again about the enthusiasm and commitment of our staff, who deal with the challenges of their roles with professionalism. The Wales and South West of England was the first geographical area to be chosen for this type of inspection, and we valued the opportunity this snapshot in time presented to us as a lever for improvement. Sine the inspection we have been implementing many of the recommendations but there is of course much more to be done and we welcome the opportunity of presenting our proposals here. We are pleased the inspection recognises that we have done a lot since regionalisation and the bringing together of immigration and customs functions at the border. The Agency welcomes the recommendations to further improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the operations in Wales and the South West of England. The recommendations are that the Agency: 1. Ensures targets and priorities are made clear to all staff, and introduces working practices to minimise possible conflicts and maximise cross-functional working. 1.1 The UK Border Agency accepts this recommendation. 1.2 The Chief Inspector has acknowledged that in Immigration Group regional targets are clearly set out in the regional Business Plan which has been issued to all staff. -

Supplementary Estimates Memorandum (2020/21) for the Home Office

Supplementary Estimates Memorandum (2020/21) for the Home Office 1 Overview 1.1 Objectives The Home Office’s objectives, as set out in its published Single Departmental Plan, are as follows: 1. Improve public safety and security 2. Strengthen the border, immigration and citizenship system 3. Maximise the benefits of the UK leaving the EU 4. Improve our corporate services Home Office spending is designed to support its objectives. Detail of which spending programmes relate to which objectives is given at Section 3.1. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/home-office-single-departmental-plan/home-office-single- departmental-plan--3. Cabinet Office is proposing to replace the Single Departmental Plan with Outcome Delivery Plans, to be published in April 2021. 1.2 Spending controls Home Office spending is broken down into several different spending totals, for which Parliament’s approval is sought. The spending totals which Parliament votes are: • Resource Departmental Expenditure Limit (“Resource DEL”) This incorporates the day-to-day running costs for front line services including the Enablers support function. This includes, but is not restricted to, the control of immigration, securing the UK border, counter-terrorism and intelligence, and the responsibility for the fire and rescue services. Income is generated from services such as issuing work permits, visas and passports. • Capital Departmental Expenditure Limit (“Capital DEL”) This encompasses the investment in the Home Office’s infrastructure enabling it to deliver its core activities and includes equipment and IT. • Resource Annually Managed Expenditure (“Resource AME”) Less predictable day to day spending such as contributions for the Police and Fire Pensions and Pension scheme management charges. -

Application for the Review of a Premises Licence Or Club Premises Certificate Under the Licensing Act 2003

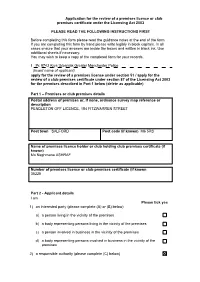

Application for the review of a premises licence or club premises certificate under the Licensing Act 2003 PLEASE READ THE FOLLOWING INSTRUCTIONS FIRST Before completing this form please read the guidance notes at the end of the form. If you are completing this form by hand please write legibly in block capitals. In all cases ensure that your answers are inside the boxes and written in black ink. Use additional sheets if necessary. You may wish to keep a copy of the completed form for your records. I Pc 8743 Krys Urbaniak Greater Manchester Police (Insert name of applicant) apply for the review of a premises licence under section 51 / apply for the review of a club premises certificate under section 87 of the Licensing Act 2003 for the premises described in Part 1 below (delete as applicable) Part 1 – Premises or club premises details Postal address of premises or, if none, ordnance survey map reference or description PENDLETON OFF LICENCE, 154 FITZWARREN STREET Post town SALFORD Post code (if known) M6 5RS Name of premises licence holder or club holding club premises certificate (if known) Ms Naghmana ASHRAF Number of premises licence or club premises certificate (if known 35225 Part 2 - Applicant details I am Please tick yes 1) an interested party (please complete (A) or (B) below) a) a person living in the vicinity of the premises b) a body representing persons living in the vicinity of the premises c) a person involved in business in the vicinity of the premises d) a body representing persons involved in business in the vicinity of -

UK Visas and Citizenship Service and Support Centres - Domestic Violence (DV) Customers

UK Visas and Citizenship Service and Support Centres - Domestic Violence (DV) Customers Factsheet: May 2021 • In November 2018, UK Visas and Immigration (UKVI) introduced new, front end services, allowing customers in the UK to submit all necessary evidence and personal information to support their application quickly and securely through a simpler journey. • From March 2019, these new services also included enhanced support for vulnerable customers, with access to 7 dedicated UKVI Service and Support Centres (SSCs). • The SSCs are in Belfast, Cardiff, Croydon, Glasgow, Liverpool, Sheffield and Solihull. • The SSCs provide a service for those customers who may be in positions of vulnerability or whose circumstances may be complex. All SSC appointments are free of charge. • From 26 May 2021, customers applying for indefinite leave to remain on the grounds that they are the victim of domestic violence or abuse (DV) will be required to attend a SSC in order to enrol their biometrics. • Customers will be automatically guided to the booking system to book an appointment at a SSC to complete their application. At the end of their online application they will get confirmation of their appointment details, including the location of the SSC, and the date and time of their appointment. • During appointments at SSCs, a trained UKVI staff member will enrol the customer’s biometric information. All SSCs have implemented COVID-secure measures and are complying with the government’s guidance on managing the risk of COVID-19. At present, and as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, DV customers will continue to submit their supporting documents separately, either by email or post.