UNCORRECTED TRANSCRIPT of ORAL EVIDENCE to Be Published As HC 1774-Iv

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christian Formation: Where Do We Start? Fulfilling the Promise of Newman's Second Spring a Synthetic Universe Same-Sex Marriag

January and February 2012 “ Pullout” Volume 44 Number 1 Price £4.50 faithPROMOTING A NEW SYNTHESIS OF FAITH AND REASON Christian Formation: Where Do We Start? Editorial Fulfilling the Promise of Newman’s Second Spring James Tolhurst A Synthetic Universe Edward Holloway Same-sex Marriage and an Uncertain Church Niall Gooch Also William Oddie on varied Catholic responses to homosexual “rights” Dylan James responds to correspondence on the purpose of sex Johann Christian Arnold on singleness and union Robert Colquhoun on a guide to purity Brendan MacCarthy and Peter Mitchell on pro-life practice And Reviews of two responses to the New Atheism www.faith.org.uk A special series of pamphlets REASONS FOR BELIEVING from Faith Movement Straightforward, up to date and well argued pamphlets on basic issues of Catholic belief, this new series will build into a single, coherent apologetic vision of the Christian Mystery. They bring out the inner coherence of Christian doctrine and show how God’s revelation makes sense of our own nature and of our world. Five excellent pamphlets in the series are now in print. Can we be sure God exists? What makes Man unique? The Disaster of Sin Jesus Christ Our Saviour Jesus Christ Our Redeemer NEW The Church: Christ’s Voice to the World To order please write to Sr Roseann Reddy, Faith-Keyway Trust Publications Office, 104 Albert Road, Glasgow G42 8DR or go to www.faith.org.uk Catholicism a New Synthesis faith summer by Edward Holloway conference Pope John Paul II gave the blueprint for catechetical renewal with the Catechism of the Catholic Church. -

Conservative Party Strategy, 1997-2001: Nation and National Identity

Conservative Party Strategy, 1997-2001: Nation and National Identity A dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy , Claire Elizabeth Harris Department of Politics, University of Sheffield September 2005 Acknowledgements There are so many people I'd like to thank for helping me through the roller-coaster experience of academic research and thesis submission. Firstly, without funding from the ESRC, this research would not have taken place. I'd like to say thank you to them for placing their faith in my research proposal. I owe a huge debt of gratitude to Andrew Taylor. Without his good humour, sound advice and constant support and encouragement I would not have reached the point of completion. Having a supervisor who is always ready and willing to offer advice or just chat about the progression of the thesis is such a source of support. Thank you too, to Andrew Gamble, whose comments on the final draft proved invaluable. I'd also like to thank Pat Seyd, whose supervision in the first half of the research process ensured I continued to the second half, his advice, experience and support guided me through the challenges of research. I'd like to say thank you to all three of the above who made the change of supervisors as smooth as it could have been. I cannot easily put into words the huge effect Sarah Cooke had on my experience of academic research. From the beginnings of ESRC application to the final frantic submission process, Sarah was always there for me to pester for help and advice. -

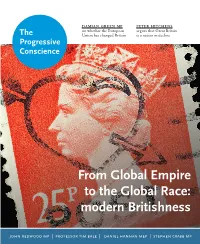

Peter Hitchens on Whether the European Argues That Great Britain the Union Has Changed Britain Is a Nation in Decline Progressive Conscience

DAMIAN GREEN MP PETER HITCHENS on whether the European argues that Great Britain The Union has changed Britain is a nation in decline Progressive Conscience From Global Empire to the Global Race: modern Britishness john redwood mp | professor tim bale | daniel hannan mep | stephen crabb mp Contents 03 Editor’s introduction 18 Daniel Hannan: To define Contributors James Brenton Britain, look to its institutions PROF TIM BALE holds the Chair James Brenton politics in Politics at Queen Mary 20 Is Britain still Great? University of London 04 Director’s note JAMES BRENTON is the editor of Peter Hitchens and Ryan Shorthouse Ryan Shorthouse The Progressive Conscience 23 Painting a picture of Britain NICK CATER is Director of 05 Why I’m a Bright Blue MP the Menzies Research Centre Alan Davey George Freeman MP in Australia 24 What’s the problem with STEPHEN CRABB MP is Secretary 06 Replastering the cracks in the North of State for Wales promoting British values? Professor Tim Bale ROSS CYPHER-BURLEY was Michael Hand Spokesman to the British 07 Time for an English parliament Embassy in Tel Aviv 25 Multiple loyalties are easy John Redwood MP ALAN DAVEY is the departing Damian Green MP Arts Council Chief Executive 08 Britain after the referendum WILL EMKES is a writer 26 Influence in the Middle East Rupert Myers GEORGE FREEMAN MP is the Ross Cypher-Burley Minister for Life Sciences 09 Patriotism and Wales DR ROBERT FORD lectures at 27 Winning friends in India Stephen Crabb MP the University of Manchester Emran Mian DAMIAN GREEN MP is the 10 Unionism -

Is There an English Nationalism?

ESSAY Is there an English Nationalism? Richard English April 2011 © ippr 2011 Institute for Public Policy Research Challenging ideas – Changing policy About ippr The Institute for Public Policy Research (ippr) is the UK’s leading progressive think tank, producing cutting-edge research and innovative policy ideas for a just, democratic and sustainable world. Since 1988, we have been at the forefront of progressive debate and policymaking in the UK. Through our independent research and analysis we define new agendas for change and provide practical solutions to challenges across the full range of public policy issues. With offices in both London and Newcastle, we ensure our outlook is as broad-based as possible, while our international work extends our partnerships and influence beyond the UK, giving us a truly world-class reputation for high-quality research. ippr, 4th Floor, 13–14 Buckingham Street, London WC2N 6DF +44 (0)20 7470 6100 • [email protected] • www.ippr.org Registered charity no. 800065 This paper was first published in April 2011. © 2011 The contents and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors only. About the author Richard English is Professor of Politics and the Director of Centre for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence at the University of St Andrews. His books include Terrorism: How to Respond (2010), Irish Freedom: The History of Nationalism in Ireland (2006), Armed Struggle: The History of the IRA (2003), and Rethinking British Decline with Michael Kenny (2000). Acknowledgments This paper forms part of ippr’s English Questions project which is kindly supported by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY A. INTERVIEWS Jacob Rees-Mogg MP (London), 9th February 2016. Jesse Norman MP (London), 12th September 2016. Nicholas Winterton (Cheshire), 23rd September 2016. Ann Winterton (Cheshire), 23rd September 2016. Peter Hitchens (London), 11th October 2016. Anne Widdecombe (London), 11th October 2016. Lord Salisbury (London), 12th October 2016. Sir William Cash MP (London), 13th October 2016. Sir Edward Leigh MP (London), 17th January 2017. David Burrowes MP (London), 17th January 2017. Charles Moore (London), 17th January 2017. Philip Davies MP (London), 19th January 2017. Sir Gerald Howarth MP (London), 19th January 2017. Dr. Myles Harris (London), 27th January 2017. Lord Sudeley (London), 6th February 2017. Jonathan Aitken (London), 6th February 2017. David Nicholson (London), 13th February 2017. Gregory Lauder-Frost (telephone), 23rd February 2017. Richard Ritchie (London), 8th March 2017. Tim Janman (London), 27th March 2017. Lord Deben (London), 4th April 2017. Lord Griffths of Fforestfach (London), 6th April 2017. Lord Tebbit (London), 6th April 2017. Sir Adrian Fitzgerald (London), 10th April 2017. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020 191 K. Hickson, Britain’s Conservative Right since 1945, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27697-3 192 BIBLIOGRAPHY Edward Norman (telephone), 28th April 2017. Cedric Gunnery (London), 2nd May 2017. Paul Bristol (London), 3rd May 2017. Harvey Thomas (London), 3rd May 2017. Ian Crowther (telephone), 12th May 2017. Iain Duncan Smith MP (London), 4th July 2017. Angela Ellis-Jones (London), 4th July 2017. John Hayes MP (London), 4th July 2017. Dennis Walker (London), 24th July 2017. Lord Howard of Lympne (London), 12th September 2017. -

Ethics and Biophilia

Rupert Lay ETHICS AND BIOPHILIA A Constructivist Critique of Enlightenment FD 180606 Rupert Lay ETHICS AND BIOPHILIA A Constructivist Critique of Enlightenment Short version of his book >> About the love of life << by Jonathan Keir (Editor) Karl Schlecht Stiftung (KSG) 2018 ISBN 978-3-00-060065-4 © Jonathan Keir für die Karl Schlecht Stiftung (KSG) 2018 Gutenbergstraße 4 72631 Aichtal www.karlschlechtstiftung.de First printed in 2018 Herausgegeben von Jonathan Keir für die Karl Schlecht Stiftung, die die zentralen Elemente der Ethik Rupert Lays für englisch- sprachige Menschen zugänglich machen wollte. Die Verantwortung für die angemessene Widergabe und für mögliche Missverständnisse liegt beim Übersetzer Jonathan Keir. All rights from texts and pictures published here, including abridged reproductions, for any public use by means of electronic or other methods of reproduction must remain reserved for the author. Contents Translator’s Foreword 4 Prologue 7 1. What is Constructivism? 10 2. The Roots of Ethics 19 3. Talking Terms 32 4. Biophilia: Where Reality Meets Itself 47 5. God is Love 60 6. The Limits of Ethical Responsibility 68 Epilogue 73 Bibliography 74 3 Translator’s Foreword We need to know the difference between how things are and how they ought to be, or what do we live and die for? Peter Hitchens Do not, dear reader, be dissuaded by the forbidding subtitle of this little book. Rupert Lay (1929-), an outcast German Jesuit currently residing in Frankfurt, certainly presents the 21st-century reader with some challenges; I mean it as a compliment when I say that his German prose reaches us from a bygone era. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Tribune, December 3, 1943, in Paul Anderson ed. Orwell in Tribune (London: Politico’s, 2006), 57. 2. Margaret Tapster, WW2 People’s War, an online archive of wartime memories con- tributed by members of the public and gathered by the BBC. The archive can be found at bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/ 65/a5827665.shtml Accessed May 30, 2013. 3. Paul Addison, No Turning Back: The Peacetime Revolutions of Post-War Britain (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2010); Peter Hennessy, Having It So Good: Britain in the Fifties (London: Allen Lane, 2006); David Kynaston Aus- terity Britain, 1945–51 (London, Berlin and New York: Bloomsbury, 2007); David Kynaston, Family Britain, 1951–1957 (London, Berlin, New York: Bloomsbury, 2009); Mark Donnelly, Sixties Britain: Culture, Society and Politics (Harlow: Pearson, 2005); Alwyn W. Turner, Crisis? What Crisis? Britain in the 1970s (London: Aurum Press, 2008); Andy Beckett, When the Lights Went Out: Britain in the Seventies (London: Faber and Faber, 2009); Dominic Sandbrook, Seasons in the Sun: The Battle for Britain, 1974–1979 (London: Allen Lane, 2012); Alwyn W. Turner, Rejoice! Rejoice! Britain in the 1980s (London: Aurum, 2010) and Andy McSmith, No Such Thing as Society: A History of Britain in the 1980s (London: Constable, 2011). 4. British and European resistance to American culture is expounded by Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style (London and New York: Routledge, 1979); Rob Kroes et al. Cultural Transmissions and Receptions: American Mass Culture in Europe (Amsterdam: VU University Press, 1993) and Rob Kroes, If You’ve Seen One, You’ve Seen the Mall: Europeans and American Mass Culture (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1996). -

How the New Atheists Are Reminding the Humanities of Their Place and Purpose in Society

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2018 The emperor's new clothes: how the new atheists are reminding the humanities of their place and purpose in society. David Ira Buckner University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Buckner, David Ira, "The emperor's new clothes: how the new atheists are reminding the humanities of their place and purpose in society." (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3112. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3112 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EMPEROR’S NEW CLOTHES: HOW THE NEW ATHEISTS ARE REMINDING THE HUMANITIES OF THEIR PLACE AND PURPOSE IN SOCIETY By David Ira Buckner B.S., East Tennessee State University, 2006 M.A., East Tennessee State University, 2008 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy -

One Nation, Disconnected Party: the Evocation of One Nation Aimed to Unite the Nation, Instead It Highlighted the Labour Party’S Divisions

Batrouni, D. (2017). One Nation, disconnected party: The evocation of One Nation aimed to unite the nation, instead it highlighted the Labour party’s divisions. British Politics, 12(3), 432-448. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41293-017-0054-8 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1057/s41293-017-0054-8 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Palgrave Macmillan at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/s41293-017-0054-8 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ One Nation, disconnected party The evocation of One Nation aimed to unite the nation, instead it highlighted the Labour party’s divisions. Dimitri Batrouni School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1TB Abstract: This paper explores Ed Miliband’s evocation of One Nation in his 2012 Labour party conference speech. It first surveys the views of members of the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) and key advisors to Miliband on One Nation, with a focus on the debates surrounding its purpose and substance. What becomes clear is the amount of confusion amongst backbenchers and shadow cabinet members of the PLP regarding its purpose. -

A List of the 238 Most Respected Journalists, As Nominated by Journalists in the 2018 Journalists at Work Survey

A list of the 238 most respected journalists, as nominated by journalists in the 2018 Journalists at Work survey Fran Abrams BBC Radio 4 & The Guardian Seth Abramson Freelance investigative journalist Kate Adie BBC Katya Adler BBC Europe Jonathan Ali BBC Christiane Amanpour CNN Lynn Ashwell Formerly Bolton News Mary-Ann Astle Stoke on Trent Live Michael Atherton The Times and Sky Sports Sue Austin Shropshire Star Caroline Barber CN Group Lionel Barber Financial Times Emma Barnett BBC Radio 5 Live Francis Beckett Author & journalist Vanessa Beeley Blogger Jessica Bennett New York Times Heidi Blake BuzzFeed David Blevins Sky News Ian Bolton Sky Sports News Susie Boniface Daily Mirror Samantha Booth Islington Tribune Jeremy Bowen BBC Tom Bradby ITV Peter Bradshaw The Guardian Suzanne Breen Belfast Telegraph Billy Briggs Freelance Tom Bristow Archant investigations unit Samuel Brittan Financial Times David Brown The Times Fiona Bruce BBC Michael Buchanan BBC Jason Burt Daily Telegraph & Sunday Telegraph Carole Cadwalladr The Observer & The Guardian Andy Cairns Sky Sports News Michael Calvin Author Duncan Campbell Investigative journalist and author Severin Carrell The Guardian Reeta Chakrabarti BBC Aditya Chakrabortty The Guardian Jeremy Clarkson Broadcaster, The Times & Sunday Times Matthew Clemenson Ilford Recorder and Romford Recorder Michelle Clifford Sky News Patrick Cockburn The Independent Nick Cohen Columnist Teilo Colley Press Association David Conn The Guardian Richard Conway BBC Rob Cotterill The Sentinel, Staffordshire Alex Crawford -

Chris Wallace the Greatest Generation the Wheelhouse Talks

FALL 2020 SCHEDULE OF EVENTS ACCESS PAST HAUENSTEIN CENTER EVENTS AT: YOUTUBE.COM/USER/HAUENSTEINCENTER Chris Wallace The Greatest Generation In remembrance of the Greatest Generation – the men and women who fought in World War II – the Hauenstein Center was proud to partner with the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Foundation, Gerald R. Ford 7PM, Wednesday, September 2, 2020 Presidential Library and Museum, and a host of community partners for a two day celebration. Tuesday, September 1, was complete with a bell ringing ceremony and lecture from Jim DeFelice, author of Every youtu.be/YKDFcULov2w Man a Hero: A Memoir of D-Day. A military flyover Grand Rapids started the second day of celebration. On Wednesday evening, host of Fox News Sunday, Chris Wallace joined Joel Westphal of the Ford Library and Museum for a discussion on his new book, Countdown 45: The Extraordinary Story of The Atomic Bomb and the 116 Days That Changed The World. CLA Alumni Panel The Wheelhouse Talks Leading Through Change In what has become a tradition at the Hauenstein Center, we kicked off our Wheelhouse Talk series with the second installment in a panel of alumni from the Peter C. Cook Leadership Academy on Friday, September 4PM, Friday September 11, 2020 11. Moderated by Alex Agbabian, a senior in the leadership academy, the panelists – Claudia Pohlen, Jonathan Cook, Nicole Horne, and Joshua Lunger – discussed leadership through the COVID-19 pandemic, feeling authentic in yourself and your role, and a host of other topics relevant to our new cohort of fellow youtu.be/EGA7xgl6eBE candidates. Paula Monopoli Centennial of the Twenty twenty marked the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, giving many Nineteenth Amendment women across the country the right to vote. -

LCMS Commission on Theology and Church Relations (CTCR) — Evaluation — New Atheists

The New Atheists History, Beliefs, Practices Identity: An atheist is a person who does not believe in the existence of a god or gods (in contrast to an agnostic, who believes that the existence of a god cannot be known with any certainty). The term “New Atheist” generally refers to popular 21st century atheist authors who are considered “new” because, instead of holding quiet, personal opinions, they boldly promote their criticism of all religious beliefs.1 Founder: There is no single founder for New Atheism. Popular New Atheist authors include Daniel Dennet (b.1942), Sam Harris (b.1967), Richard Dawkins (b.1941), and Christopher Hitchens (1949-2011). Statistics: The extent of New Atheist influence is not clear, but according to a 2014 Pew Research Center study, the number of Americans who identify as atheists doubled since a survey done in 2007. About 3.1% of Americans call themselves atheists, and 4% call themselves agnostics.2 According to a 2015 survey by Gallup International, 11% of the people surveyed worldwide considered themselves to be “convinced atheists.”3 History: Atheism is not a recent development, although in earlier centuries, atheism was for most people an unacceptable worldview. Modern atheism stems from the elevation of human reason during the Enlightenment of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when alternatives to the biblical worldview were more widely embraced. For the New Atheists, the loss of belief in God is hardly more damaging to the culture than outgrowing a belief in Santa Claus. In contrast, atheists of the 1 “The New Atheists are, in their own way, evangelistic in intent and ambitious in hope.