WHITE SAGE Fire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sahnish (Arikara) Ethnobotany

Kindscher, L. Yellow Bird, M. Yellow Bird & Sutton Yellow M. Bird, Yellow L. Kindscher, Sahnish (Arikara) Ethnobotany This book describes the traditional use of wild plants among the Arikara (Sahnish) for food, medicine, craft, and other uses. The Arikara grew corn, hunted and foraged, and traded with other tribes in the northern Great Plains. Their villages were located along the Sahnish (Arikara) Missouri River in northern South Dakota and North Dakota. Today, many of them live at Fort Berthold Reservation, North Dakota, as part of the MHA (Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara) Ethnobotany Nation. We document the use of 106 species from 31 plant families, based primarily on the work of Melvin Gilmore, who recorded Arikara ethnobotany from 1916 to 1935. Gilmore interviewed elders for their stories and accounts of traditional plant use, collected material goods, and wrote a draft manuscript, but was not able to complete it due to debilitating illness. Fortunately, his field notes, manuscripts, and papers were archived and form the core of the present volume. Gilmore’s detailed description is augmented here with historical accounts of the Arikara gleaned from the journals of Great Plains explorers—Lewis and Clark, John Bradbury, Pierre Tabeau, and others. Additional plant uses and nomenclature is based on the field notes of linguist Douglas R. Parks, who carried out detailed documentation of the Sahnish (Arikara) Ethnobotany tribe’s language from 1970–2001. Although based on these historical sources, the present volume features updated modern botanical nomenclature, contemporary spelling and interpretation of Arikara plant names, and color photographs and range maps of each species. -

Biological Survey of a Prairie Landscape in Montana's Glaciated

Biological Survey of a Prairie Landscape in Montanas Glaciated Plains Final Report Prepared for: Bureau of Land Management Prepared by: Stephen V. Cooper, Catherine Jean and Paul Hendricks December, 2001 Biological Survey of a Prairie Landscape in Montanas Glaciated Plains Final Report 2001 Montana Natural Heritage Program Montana State Library P.O. Box 201800 Helena, Montana 59620-1800 (406) 444-3009 BLM Agreement number 1422E930A960015 Task Order # 25 This document should be cited as: Cooper, S. V., C. Jean and P. Hendricks. 2001. Biological Survey of a Prairie Landscape in Montanas Glaciated Plains. Report to the Bureau of Land Management. Montana Natural Heritage Pro- gram, Helena. 24 pp. plus appendices. Executive Summary Throughout much of the Great Plains, grasslands limited number of Black-tailed Prairie Dog have been converted to agricultural production colonies that provide breeding sites for Burrow- and as a result, tall-grass prairie has been ing Owls. Swift Fox now reoccupies some reduced to mere fragments. While more intact, portions of the landscape following releases the loss of mid - and short- grass prairie has lead during the last decade in Canada. Great Plains to a significant reduction of prairie habitat Toad and Northern Leopard Frog, in decline important for grassland obligate species. During elsewhere, still occupy some wetlands and the last few decades, grassland nesting birds permanent streams. Additional surveys will have shown consistently steeper population likely reveal the presence of other vertebrate declines over a wider geographic area than any species, especially amphibians, reptiles, and other group of North American bird species small mammals, of conservation concern in (Knopf 1994), and this alarming trend has been Montana. -

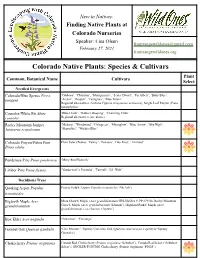

Finding Native Plants at Colorado Nurseries Speaker: Lisa Olsen [email protected] February 27, 2021 Frontrangewildones.Org

New to Natives: Finding Native Plants at Colorado Nurseries Speaker: Lisa Olsen [email protected] February 27, 2021 frontrangewildones.org Colorado Native Plants: Species & Cultivars Plant Common, Botanical Name Cultivars Select Needled Evergreens Colorado/Blue Spruce Picea ‘Globosa’, ‘Christina’, ‘Montgomery’, ‘Sester Dwarf’, ‘Fat Albert’, ‘Baby Blue’, pungens ‘Avatar’, ‘Hoopsii’, ‘Fastigiata’, ‘Blue Totem’ Regional alternatives: Arizona Cypress (Cupressus arizonica), Single Leaf Pinyon (Pinus monophylla) Concolor/White Fir Abies ‘Blue Cloak’, ‘Gable’s Weeping’, ‘Charming Chub’ concolor Regional alternatives (see above) Rocky Mountain Juniper ‘Medora’, ‘Woodward’, ‘Cologreen’, ‘Moonglow’, ‘Blue Arrow’, ‘Sky High’, Juniperus scopulorum ‘Skyrocket’, ‘Wichita Blue’ Colorado Pinyon/Piñon Pine Plant Select Petites: ‘Farmy’, ‘Penasco’, Tiny Pout’, ‘Trinidad’ Pinus edulis Ponderosa Pine Pinus ponderosa ‘Mary Ann Heacock’ Limber Pine Pinus flexilis ‘Vanderwolf’s Pyramid’, 'Tarryall', ‘Lil’ Wolf’ Deciduous Trees Quaking Aspen Populus Prairie Gold® Aspen (Populus tremuloides ‘NE Arb’) tremuloides Bigtooth Maple Acer Mesa Glow® Maple (Acer grandidentatum 'JFS-NuMex 3' PP 27930), Rocky Mountain grandidentatum Glow® Maple (Acer grandidentatum 'Schmidt'), Highland Park® Maple (Acer grandidentatum x saccharum ‘Hipzam’) Box Elder Acer negundo ‘Sensation’, ‘Flamingo’ Gambel Oak Quercus gambelii ‘Gila Monster’, 'Speedy Gonzales' Oak (Quercus macrocarpa x gambelii 'Speedy Gonzales') Chokecherry Prunus virginiana Canada Red Chokecherry (Prunus -

Molecular Phylogeny of Subtribe Artemisiinae (Asteraceae), Including Artemisia and Its Allied and Segregate Genera Linda E

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications in the Biological Sciences Papers in the Biological Sciences 9-26-2002 Molecular phylogeny of Subtribe Artemisiinae (Asteraceae), including Artemisia and its allied and segregate genera Linda E. Watson Miami University, [email protected] Paul E. Bates University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Timonthy M. Evans Hope College, [email protected] Matthew M. Unwin Miami University, [email protected] James R. Estes University of Nebraska State Museum, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscifacpub Watson, Linda E.; Bates, Paul E.; Evans, Timonthy M.; Unwin, Matthew M.; and Estes, James R., "Molecular phylogeny of Subtribe Artemisiinae (Asteraceae), including Artemisia and its allied and segregate genera" (2002). Faculty Publications in the Biological Sciences. 378. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscifacpub/378 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications in the Biological Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. BMC Evolutionary Biology BioMed Central Research2 BMC2002, Evolutionary article Biology x Open Access Molecular phylogeny of Subtribe Artemisiinae (Asteraceae), including Artemisia and its allied and segregate genera Linda E Watson*1, Paul L Bates2, Timothy M Evans3, -

Maintaining and Establishing Culturally Important Plants After Landscape

Maintaining and establishing culturally important plants after landscape scale disturbance by Marcus Kirk Denny A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Land Resources and Environmental Sciences Montana State University © Copyright by Marcus Kirk Denny (2003) Abstract: Indigenous plant species have been culturally fundamental to Native Americans for centuries. These indigenous species are becoming recognized as potentially crucial elements to indigenous plant community structure, function, and invasion resistence. Invasions by nonindigenous plant species may displace many indigenous plants. Additionally, long-term herbicide use has potentially negative impacts on indigenous forb and shrub populations, and many are culturally important to Native Americans. Research on herbicide impacts to non-target plant species is limited. The purpose of this research was to quantify indigenous species response to hand removal of an invader, sulfur cinquefoil, and five selective herbicides applied to noninvaded rangeland at three rates each. Completely randomized sulfur cinquefoil treatments were (removed and nonremoved) replicated five times at two sites. Herbicide treatments were replicated three times at each of two sites in a randomized-complete-block design and included: commercial clopyralid + 2,4-D, 2,4-D amine, metsulfuron, picloram, and clopyralid. Species canopy cover was recorded at the four sites in 1999. hi 2000, canopy cover, biomass and density were recorded in each plot. Data were analyzed using ANOVA. Indigenous forb canopy cover and richness depended on hand removal of sulfur cinquefoil. Species canopy cover, density, and biomass depended upon herbicide and rate of application. Forb canopy cover and density decreased when treated with picloram while perennial grass cover and biomass increased following some herbicide treatments. -

List of Plants for Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve

Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve Plant Checklist DRAFT as of 29 November 2005 FERNS AND FERN ALLIES Equisetaceae (Horsetail Family) Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum arvense Present in Park Rare Native Field horsetail Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum laevigatum Present in Park Unknown Native Scouring-rush Polypodiaceae (Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Cystopteris fragilis Present in Park Uncommon Native Brittle bladderfern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Woodsia oregana Present in Park Uncommon Native Oregon woodsia Pteridaceae (Maidenhair Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Argyrochosma fendleri Present in Park Unknown Native Zigzag fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cheilanthes feei Present in Park Uncommon Native Slender lip fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cryptogramma acrostichoides Present in Park Unknown Native American rockbrake Selaginellaceae (Spikemoss Family) Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella densa Present in Park Rare Native Lesser spikemoss Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella weatherbiana Present in Park Unknown Native Weatherby's clubmoss CONIFERS Cupressaceae (Cypress family) Vascular Plant Pinales Cupressaceae Juniperus scopulorum Present in Park Unknown Native Rocky Mountain juniper Pinaceae (Pine Family) Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies concolor var. concolor Present in Park Rare Native White fir Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies lasiocarpa Present -

Dakota Ethnobotany in the Carleton College Cowling Arboretum

Bibliographic Note The information in our guide was compiled from a combination of Dakota Ethnobotany in the historical and living sources. We consulted three published eth- Carleton College Cowling Arboretum nobotanical compilations: Melvin Rose Gilmore’s Uses of Plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region (1919), Patrick Mun- son’s Contributions to Osage and Lakota Ethnobotany (1981), and Prior to colonization, the Cowling Arboretum was part of Daniel Moerman’s Native American Ethnobotany (1998). We also the Oceti Šakowiŋ, or the Seven Council Fires, territory.1 All bands conducted a series of interviews with Dakota, Lakota, and Ojibwe in this political-social organization, including Dakota, Nakota, and individuals from nearby in Minnesota, as well as other scholars Lakota spoke closely related dialects of the same language. The and ethnobotanists with knowledge pertaining to these cultures. two bands that lived in our area specifically for thousands of years Our contacts included Sean Sherman, who is an Oglala Lakota prior to colonization spoke Dakota: the Bdewakaŋtoŋwaŋ (Mde- chef and the CEO/founder of The Sioux Chef in the Twin Cities; wakanton, The Spirit Lake People) and the Waĥpekute (Wahpekute, Darlene St. Clair, who is a Professor of American Indian Studies at The Shooters Among the Leaves People). St. Cloud State University; Dorene Day, an Ojibwe birthing practi- Beginning with the Pike Treaty of 1805, Colonization of tioner in the Twin Cities; Julia Uleberg-Swanson, the Dacie Moses Dakota land ‘Mni Sota Makoce’ consisted of a series of treaties in House Coordinator at Carleton and an adopted sibling of Dorene which Dakota ceded land in exchange for promised government Day; Don Hazlett, an ethnobotanist at the Denver Botanical Gar- annuity payments, which often did not come to fruition. -

Cultural Parallax and Ethnobotany

Katlyn Arnett, Davita Moyer, Jennifer Reinke, Allison Taylor 5/8/09 Geography 565 Cultural Parallax and Ethnobotany We will describe our project on Ho-Chunk ethnobotany in a narrative form implicating our roles in the research process. Out initial intention was to understand the cultural and scientific link between traditional, medicinal plant uses and contemporary Ho-Chunk women's health issues. This work included quantitative and qualitative research approaches. OUf four initial research methods were making a map ofAmerican Indian sites and original vegetation cover along the Wisconsin River, a table of local plants within the lower Wisconsin Riverway and their medical values, a study of Ho-Chunk cultural aspects ofhealing, interviews with women to gain insight on health issues. We carried on the quantitative methods but we shifted our intention due to ethical conflicts that arose during the interview process. This shift led to new research goals and arguments. To explain this shift we use the model ofstellar parallax and finally we analyze the research using environmental ethics and surveys ofidentity politics. Methods Southern Wisconsin American Indian communities historically lived closely with their natural environments. Food, clothing, and medicines are examples ofnative people's cultural interactions with local plants. The Ho-Chunk American Indian tribe is one ofeleven federally recognized Wisconsin tribes, that exemplifies a lifestyle infused with available natural resources, using plants for community traditions and tribal well-being. Physical ailments were treated using medicinal plants and herbs, in addition to shamanistic and spiritual healing methods. Female health, in particular was supported using natural remedies through plant-based medicine, specifically for reproductive purposes. -

Rare, Threatened and Endangered Species of Oregon

Portland State University PDXScholar Institute for Natural Resources Publications Institute for Natural Resources - Portland 8-2016 Rare, Threatened and Endangered Species of Oregon James S. Kagan Portland State University Sue Vrilakas Portland State University, [email protected] John A. Christy Portland State University Eleanor P. Gaines Portland State University Lindsey Wise Portland State University See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/naturalresources_pub Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Biology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Oregon Biodiversity Information Center. 2016. Rare, Threatened and Endangered Species of Oregon. Institute for Natural Resources, Portland State University, Portland, Oregon. 130 pp. This Book is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Institute for Natural Resources Publications by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Authors James S. Kagan, Sue Vrilakas, John A. Christy, Eleanor P. Gaines, Lindsey Wise, Cameron Pahl, and Kathy Howell This book is available at PDXScholar: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/naturalresources_pub/25 RARE, THREATENED AND ENDANGERED SPECIES OF OREGON OREGON BIODIVERSITY INFORMATION CENTER August 2016 Oregon Biodiversity Information Center Institute for Natural Resources Portland State University P.O. Box 751, -

The Use of Plants for Foods, Beverages and Narcotics." University of New Mexico Biological Series, V

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository UNM Bulletins Scholarly Communication - Departments 1936 The seu of plants for foods, beverages and narcotics Edward Franklin Castetter Morris Edward Opler Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/unm_bulletin Recommended Citation Castetter, Edward Franklin and Morris Edward Opler. "The use of plants for foods, beverages and narcotics." University of New Mexico biological series, v. 4, no. 5, University of New Mexico bulletin, whole no. 297, Ethnobiological studies in the American Southwest, 3 4, 5 (1936). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/unm_bulletin/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarly Communication - Departments at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNM Bulletins by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of New l\1exico Bulletin Ethnobiological Studies in the American Southwest III. The Ethnobiology 0./ the Chiricahua and Mescalero Apache :I A. THE USE OF PLANTS FOR FOODS, BEVERAGES AND. NARCOTICS I; I 1 \ By EDWARD F. CASTETTER, Professor of Biology Uni1Jcrsity of New Mexico and M. E. OPLER, Assistant Anthropologist, «--I ". ?.ffice of Jr"dian AfffLirs , • '&:Z/L'Y~'L""-k 2{,,, /ft., .,/J'/PJt,. ~?Uhrt-tY:-? 1L ;Cj~~;2. FC~~Z~ .t~ _.-~ .-- "~d:£~-I:lJl ( ; . /Jc}-. I l.-~--_--:~....£I~.p-:;:~~U~"'''lJJ''''i'~,~~~!vt:;:'_~{;2.4~~'';G."-if."!-':...:...:.._::."':.!.7:.:'L:.l!:.;'~ ,r-, I Tl : 5 \ L ._L -I 21M ~4~/rU4~ C-5t.A./.2.. Q f-( I A,A·?/1 6 - B 9./9 3 7 /115'7 The University of NeW Mexico VI tJ Bulletin WV'? Ethnobiological Studies in the American' Southwest 111. -

Artemesia - Powis Castle

Common Name: Artemesia - Powis Castle Botanical name: Artemesiax Powis Castle Plant Type: Perennial Light Requirement: High Water Requirement: Low Hardiness/Zone: 4 - 8 Heat/Drought Tolerance: High Height: 3 ft Width/Spacing: 3ft Flower Color: Yellow Blooming Period: Rarely flowers Plant Form or Habit: Evergreen woody perennial, or shrub Foliage Color and Texture: Leaves are finely dissected like filigreed silver lacework. Silvery gray foliage Butterfly or bird attracter: No Deer Resistant: Usually Plant Use: Rock garden, herb garden or stand alone specimen Aromatic, lace-like; blue-gray foliage; berries are beautiful; low water use and low maintenance Additional comments: Powis Castle benefits from pruning to keep it in a compact mound. But don't prune in fall; prune when new growth starts in spring. Has a tendency to up and die rather unexpectedly. Non- Native – adapted. 36” x 30” wide, (cutting propagated). This is a very underused ornamental sage. With dissected silver- gray foliage, it is the perfect companion plant to use with other flowering perennials and ornamental grasses to bring out interesting contrasts of leaf color and texture. It almost never flowers, thus maintaining its neat appearance with no extra effort. Not at all fussy as to soil type, “Powis Castle” is also quite drought tolerant. Zones 4-9. Source: http://www.ci.austin.tx.us/growgreen/plantguide/viewdetails.cfm?plant_id=207 http://aggie-horticulture.tamu.edu/herbaceous/artemisiapowis.html Extension programs service people of all ages regardless of socioeconomic level, race, color, sex, religion, disability, or national origin. The Texas A&M University System, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the County Commissioners Courts of Texas Cooperating A member of The Texas A&M University System and its statewide Agriculture Program. -

Artemisia Ludoviciana Nutt. Var. Latiloba, Var. Ludoviciana, and Var

Plant Propagation Protocol for Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. D. Giselle Koehn ESRM 412 – Native Plant Production TAXONOMY Family Names Family ASTERACEAE Scientific Name: Family Common Sunflower Family Name: Scientific Names Genus: Artemisia Species: ludoviciana Nutt. Species Not Found Authority: Variety: var. latiloba , var. ludoviciana , and var. incompta Sub-species: Cultivar: Authority for Not Found Variety/Sub- species: Common Synonym(s) (include full scientific ARDI15 Artemisia diversifolia Rydb. names (e.g., ARGN Artemisia gnaphalodes Nutt. Elymus ARHE6 Artemisia herriotii Rydb. glaucus ARLUT Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. ssp. typica D.D. Keck Buckley), ARLUA3 Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. var. americana (Besser) Fernald including ARLUB Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. var. brittonii (Rydb.) Fernald variety or ARLUG Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. var. gnaphalodes (Nutt.) Torr. & A. Gray subspecies ARLUL3 Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. var. latifolia (Besser) Torr. & A. Gray information) ARLUP Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. var. pabularis (A. Nelson) Fernald ARPA23 Artemisia pabularis (A. Nelson) Rydb. ARPU12 Artemisia purshiana Besser ARVUL2 Artemisia vulgaris L. ssp. ludoviciana (Nutt.) H.M. Hall & Clem. ARVUL3 Artemisia vulgaris L. var. ludoviciana (Nutt.) Kuntze (2) Common Western sage, White Sage, western mugwort, prairie sagebrush, Artemisia, silver Name(s): queen, wormwood Species Code (as ARTLUD per USDA Plants database): GENERAL INFORMATION Geographical ludoviciana occurs from low to high elevations, from B.C. to California and range Mexico, east to Ontario, Illinois, and Arkansas. It is not found west of the (distribution Cascades, except as an occasional introduction. maps for It occupies dry open sites and disturbed areas from the plains and foothills to the North alpine zone in the mountains. White sage is a diverse species, with several America and subspecies that intergrade in areas of overlapping occurrence.(1) Washington Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt.