Cultural Parallax and Ethnobotany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plant List Bristow Prairie & High Divide Trail

*Non-native Bristow Prairie & High Divide Trail Plant List as of 7/12/2016 compiled by Tanya Harvey T24S.R3E.S33;T25S.R3E.S4 westerncascades.com FERNS & ALLIES Pseudotsuga menziesii Ribes lacustre Athyriaceae Tsuga heterophylla Ribes sanguineum Athyrium filix-femina Tsuga mertensiana Ribes viscosissimum Cystopteridaceae Taxaceae Rhamnaceae Cystopteris fragilis Taxus brevifolia Ceanothus velutinus Dennstaedtiaceae TREES & SHRUBS: DICOTS Rosaceae Pteridium aquilinum Adoxaceae Amelanchier alnifolia Dryopteridaceae Sambucus nigra ssp. caerulea Holodiscus discolor Polystichum imbricans (Sambucus mexicana, S. cerulea) Prunus emarginata (Polystichum munitum var. imbricans) Sambucus racemosa Rosa gymnocarpa Polystichum lonchitis Berberidaceae Rubus lasiococcus Polystichum munitum Berberis aquifolium (Mahonia aquifolium) Rubus leucodermis Equisetaceae Berberis nervosa Rubus nivalis Equisetum arvense (Mahonia nervosa) Rubus parviflorus Ophioglossaceae Betulaceae Botrychium simplex Rubus ursinus Alnus viridis ssp. sinuata Sceptridium multifidum (Alnus sinuata) Sorbus scopulina (Botrychium multifidum) Caprifoliaceae Spiraea douglasii Polypodiaceae Lonicera ciliosa Salicaceae Polypodium hesperium Lonicera conjugialis Populus tremuloides Pteridaceae Symphoricarpos albus Salix geyeriana Aspidotis densa Symphoricarpos mollis Salix scouleriana Cheilanthes gracillima (Symphoricarpos hesperius) Salix sitchensis Cryptogramma acrostichoides Celastraceae Salix sp. (Cryptogramma crispa) Paxistima myrsinites Sapindaceae Selaginellaceae (Pachystima myrsinites) -

Lower Wisconsin State Riverway Visitor River in R W S We I N L O S Co

Lower Wisconsin State Riverway Visitor River in r W s we i n L o s co Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources ● Lower Wisconsin State Riverway ● 1500 N. Johns St. ● Dodgeville, WI 53533 ● 608-935-3368 Welcome to the Riverway Please explore the Lower Wisconsin State bird and game refuge and a place to relax Riverway. Only here can you fi nd so much while canoeing. to do in such a beautiful setting so close Efforts began in earnest following to major population centers. You can World War Two when Game Managers fi sh or hunt, canoe or boat, hike or ride began to lease lands for public hunting horseback, or just enjoy the river scenery and fi shing. In 1960 money from the on a drive down country roads. The Riv- Federal Pittman-Robinson program—tax erway abounds in birds and wildlife and moneys from the sale of sporting fi rearms the history of Wisconsin is written in the and ammunition—assisted by providing bluffs and marshes of the area. There is 75% of the necessary funding. By 1980 something for every interest, so take your over 22,000 acres were owned and another pick. To really enjoy, try them all! 7,000 were held under protective easement. A decade of cooperative effort between Most of the work to manage the property Citizens, Environmental Groups, Politi- was also provided by hunters, trappers and cians, and the Department of Natural anglers using license revenues. Resources ended successfully with the passage of the law establishing the Lower About the River Wisconsin State Riverway and the Lower The upper Wisconsin River has been called Wisconsin State Riverway Board. -

Dietary Supplements Compendium 2019 Edition

Products and Services New Dietary Supplements Reference Standards Below is a list of newly released Reference Standards. Herbal Medicines/ Botanical Dietary Supplements Baicalein Baicalein 7-O-Glucuronide Chebulagic Acid Dietary Supplements Compendium 2019 Edition Coptis chinensis Rhizome Dry Extract In response to the customer feedback, coupled with evolving information needs, USP moved the Psoralen Dietary Supplements Compendium (DSC) to an online platform for the 2019 edition. DSC continues Scutellaria baicalensis Root Dry to provide in-depth, comprehensive information for all phases of development and manufacturing of Extract quality dietary supplements including quality control, quality assurance, and regulatory/compendial Terminalia chebula Fruit Dry affairs. Extract Guarana Seed Dry Extract Some of the advantages that come with the new online DSC edition include: Cullen Corylifolium Fruit Dry Extract More frequent updates to ensure access to the most current information Procyanidin B2 Customizable alerts to notify of changes to selected documents An intuitive interface to facilitate quick and easy navigation Non-Botanicals A customizable workspace with bookmarks, alerts and a viewing history beta-Glycerylphosphorylcholine Convenient, anytime, anywhere access with common browsers Conjugated Linoleic Acids – In addition to selected new and revised monographs and General Chapters from the USP-NF and Triglycerides Food Chemicals Codex issued since the previous 2015 edition, the DSC 2019 features: Creatine Docosahexaenoic Acid 24 new General Chapters Eicosapentaenoic Acid 72 new dietary ingredient and dietary supplement monographs L-alpha- 27 sets of supplementary information for botanical and nonbotanical dietary supplements Glycerophosphorylethanolamine 59 updated botanical HPTLC plates L-alpha- Revised and updated dietary intake comparison tables Glycerylphosphorylcholine Updated Dietary Supplement Verification Program manual Omega-3 Free Fatty Acids Pyrroloquinoline Quinone View this page for more information or to subscribe to the 2019 online DSC. -

Sahnish (Arikara) Ethnobotany

Kindscher, L. Yellow Bird, M. Yellow Bird & Sutton Yellow M. Bird, Yellow L. Kindscher, Sahnish (Arikara) Ethnobotany This book describes the traditional use of wild plants among the Arikara (Sahnish) for food, medicine, craft, and other uses. The Arikara grew corn, hunted and foraged, and traded with other tribes in the northern Great Plains. Their villages were located along the Sahnish (Arikara) Missouri River in northern South Dakota and North Dakota. Today, many of them live at Fort Berthold Reservation, North Dakota, as part of the MHA (Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara) Ethnobotany Nation. We document the use of 106 species from 31 plant families, based primarily on the work of Melvin Gilmore, who recorded Arikara ethnobotany from 1916 to 1935. Gilmore interviewed elders for their stories and accounts of traditional plant use, collected material goods, and wrote a draft manuscript, but was not able to complete it due to debilitating illness. Fortunately, his field notes, manuscripts, and papers were archived and form the core of the present volume. Gilmore’s detailed description is augmented here with historical accounts of the Arikara gleaned from the journals of Great Plains explorers—Lewis and Clark, John Bradbury, Pierre Tabeau, and others. Additional plant uses and nomenclature is based on the field notes of linguist Douglas R. Parks, who carried out detailed documentation of the Sahnish (Arikara) Ethnobotany tribe’s language from 1970–2001. Although based on these historical sources, the present volume features updated modern botanical nomenclature, contemporary spelling and interpretation of Arikara plant names, and color photographs and range maps of each species. -

Echinacea Purpurea Extracts (Echinacin) and Thymostimulin

SUMMARY OF DATA FOR CHEMICAL SELECTION Echinacea BASIS OF NOMINATION TO THE CSWG Echinacea is presented to the CSWG as part of a review of botanicals being used as dietary supplements in the United States. Alternative herbal medicines are projected to be a $5 billion market by the turn of the century. Echinacea is an extremely popular herbal supplement; sales are nearly $300 million a year according to the last figures available. Sweeping deregulation of botanicals now permits echinacea to be sold to the public without proof of safety or efficacy if the merchandiser notes on the label that the product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. The literature on echinacea clearly showed that it is being used for the treatment of viral and bacterial infections although virtually no information on safety was found. INPUT FROM GOVERNMENT AGENCIESIINDUSTRY According to the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, FDA does not have information about the safety or purported benefits of echinacea. SELECTION STATUS • ACTION BY CSWG: 4/28/98 Studies requested: - Toxicological evaluation, to include 90-day subchronic study - Carcinogenicity, depending on the results of the toxicologic evaluation - Micronucleus assay Priority: Moderate RationalelRemarks: - Potential for widespread human exposure. - Most popular herbal supplement in the US, used to stimulate immune system - Test material should be standardized to 2.4% P-l,2-d-fructofuranoside - NCI will conduct Ames Salmonella assay Echinacea CHEMICAL IDENTIFICATION Chemical Abstract Service Names: CAS Registry Numbers: Echinacea angustifolia, ext. 84696-11-7 Echinacea purpurea, ext. 90028-20-9 Echinacea pallida, ext. 97281-15-7 Echinacea angustifolia, tincture 129677-89-0 Description: Echinacea are herbaceous perennials of the daisy family. -

State of New York City's Plants 2018

STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 Daniel Atha & Brian Boom © 2018 The New York Botanical Garden All rights reserved ISBN 978-0-89327-955-4 Center for Conservation Strategy The New York Botanical Garden 2900 Southern Boulevard Bronx, NY 10458 All photos NYBG staff Citation: Atha, D. and B. Boom. 2018. State of New York City’s Plants 2018. Center for Conservation Strategy. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY. 132 pp. STATE OF NEW YORK CITY’S PLANTS 2018 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 10 DOCUMENTING THE CITY’S PLANTS 10 The Flora of New York City 11 Rare Species 14 Focus on Specific Area 16 Botanical Spectacle: Summer Snow 18 CITIZEN SCIENCE 20 THREATS TO THE CITY’S PLANTS 24 NEW YORK STATE PROHIBITED AND REGULATED INVASIVE SPECIES FOUND IN NEW YORK CITY 26 LOOKING AHEAD 27 CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEGMENTS 30 LITERATURE CITED 31 APPENDIX Checklist of the Spontaneous Vascular Plants of New York City 32 Ferns and Fern Allies 35 Gymnosperms 36 Nymphaeales and Magnoliids 37 Monocots 67 Dicots 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report, State of New York City’s Plants 2018, is the first rankings of rare, threatened, endangered, and extinct species of what is envisioned by the Center for Conservation Strategy known from New York City, and based on this compilation of The New York Botanical Garden as annual updates thirteen percent of the City’s flora is imperiled or extinct in New summarizing the status of the spontaneous plant species of the York City. five boroughs of New York City. This year’s report deals with the City’s vascular plants (ferns and fern allies, gymnosperms, We have begun the process of assessing conservation status and flowering plants), but in the future it is planned to phase in at the local level for all species. -

An Analysis of the Pollinators of Echinacea Purpurea in Relation to Their Perceived Efficiency and Color Preferences

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga UTC Scholar Student Research, Creative Works, and Honors Theses Publications 5-2021 An analysis of the pollinators of Echinacea purpurea in relation to their perceived efficiency and color efpr erences Carmen Black University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Black, Carmen, "An analysis of the pollinators of Echinacea purpurea in relation to their perceived efficiency and color efpr erences" (2021). Honors Theses. This Theses is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research, Creative Works, and Publications at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Analysis of the Pollinators of Echinacea purpurea in Relation to their Perceived Efficiency and Color Preferences Departmental Honors Thesis The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Department of Biology, Geology, and Environmental Sciences Examination Date: April 6th Dr. Stylianos Chatzimanolis Dr. Joey Shaw Professor of Biology Professor of Biology Thesis Director Department Examiner Dr. Elise Chapman Lecturer of Biology Department Examiner 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Abstract …………..…………………….………………………… 3 II. Introduction…………..………………….……………………....... 5 III. Materials and Methods…………...………………………………. 11 IV. Results…………..…………………….………………………….. 16 A. List of Figures…………...……………………………….. 21 V. Discussion…………..………….…………………………...…… 28 VI. Acknowledgements………….……………….………...………… 38 VII. Works Cited ……………………………………...……….……… 39 VIII. Appendices……………………………………………………….. 43 3 ABSTRACT This study aimed to better understand how insects interacted with species of Echinacea in Tennessee and specifically their preference to floral color. Based on previous studies I expected the main visitors to be composed of various bees, beetles and butterflies. -

WHITE SAGE Fire

Plant Guide or sweat lodge) with the flowering end toward the WHITE SAGE fire. The leaves were burned as an incense to cleanse and drive away bad spirits, evil influences, bad Artemisia ludoviciana Nutt. Plant Symbol = ARLU dreams, bad thoughts, and sickness. A small pinch of baneberry (Actea rubra) was often mixed with it for Contributed By: USDA NRCS National Plant Data this purpose. The smoke was used to purify people, Center & University of California-Davis Arboretum spaces, implements, utensils, horses, and rifles in various ceremonies. The Lakota also make bracelets for the Sun Dance from white sage (Rogers 1980). The Cheyenne use the white sage in their Sun Dance and Standing Against Thunder ceremonies (Hart 1976). Other tribes who used white sage include the Arapaho, Comanche, Gros Ventre, Creek, Navaho, Tewa, and Ute (Nickerson 1966, Carlson and Jones 1939, Hart 1976, Thwaites 1905, Denig 1855, Elmore 1944, Robbins et al. 1916, Chamberlin 1909). The Dakota and other tribes used white sage tea for stomach troubles and many other ailments (Gilmore 1977). The Cheyenne used the crushed leaves as snuff for sinus attacks, nosebleeds, and headaches (Hart 1976). The Crow made a salve for use on sores by mixing white sage with neck-muscle fat (probably from buffalo) (Hart 1976). They used a strong tea as an astringent for eczema and as a deodorant and an antiperspirant for underarms and feet. The Kiowa made a bitter drink from white sage, which they used to reduce phlegm and to relieve a variety of lung and stomach complaints (Vestal and Shultes 1939). -

Lower Wisconsin River Main Stem

LOWER WISCONSIN RIVER MAIN STEM The Wisconsin River begins at Lac Vieux Desert, a lake in Vilas County that lies on the border of Wisconsin and the Lower Wisconsin River Upper Pennisula in Michigan. The river is approximately At A Glance 430 miles long and collects water from 12,280 square miles. As a result of glaciation across the state, the river Drainage Area: 4,940 sq. miles traverses a variety of different geologic and topographic Total Stream Miles: 165 miles settings. The section of the river known as the Lower Wisconsin River crosses over several of these different Major Public Land: geologic settings. From the Castle Rock Flowage, the river ♦ Units of the Lower Wisconsin flows through the flat Central Sand Plain that is thought to State Riverway be a legacy of Glacial Lake Wisconsin. Downstream from ♦ Tower Hill, Rocky Arbor, and Wisconsin Dells, the river flows through glacial drift until Wyalusing State Parks it enters the Driftless Area and eventually flows into the ♦ Wildlife areas and other Mississippi River (Map 1, Chapter Three ). recreation areas adjacent to river Overall, the Lower Wisconsin River portion of the Concerns and Issues: Wisconsin River extends approximately 165 miles from the ♦ Nonpoint source pollution Castle Rock Flowage dam downstream to its confluence ♦ Impoundments with the Mississippi River near Prairie du Chien. There are ♦ Atrazine two major hydropower dams operate on the Lower ♦ Fish consumption advisories Wisconsin, one at Wisconsin Dells and one at Prairie Du for PCB’s and mercury Sac. The Wisconsin Dells dam creates Kilbourn Flowage. ♦ Badger Army Ammunition The dam at Prairie Du Sac creates Lake Wisconsin. -

Biological Survey of a Prairie Landscape in Montana's Glaciated

Biological Survey of a Prairie Landscape in Montanas Glaciated Plains Final Report Prepared for: Bureau of Land Management Prepared by: Stephen V. Cooper, Catherine Jean and Paul Hendricks December, 2001 Biological Survey of a Prairie Landscape in Montanas Glaciated Plains Final Report 2001 Montana Natural Heritage Program Montana State Library P.O. Box 201800 Helena, Montana 59620-1800 (406) 444-3009 BLM Agreement number 1422E930A960015 Task Order # 25 This document should be cited as: Cooper, S. V., C. Jean and P. Hendricks. 2001. Biological Survey of a Prairie Landscape in Montanas Glaciated Plains. Report to the Bureau of Land Management. Montana Natural Heritage Pro- gram, Helena. 24 pp. plus appendices. Executive Summary Throughout much of the Great Plains, grasslands limited number of Black-tailed Prairie Dog have been converted to agricultural production colonies that provide breeding sites for Burrow- and as a result, tall-grass prairie has been ing Owls. Swift Fox now reoccupies some reduced to mere fragments. While more intact, portions of the landscape following releases the loss of mid - and short- grass prairie has lead during the last decade in Canada. Great Plains to a significant reduction of prairie habitat Toad and Northern Leopard Frog, in decline important for grassland obligate species. During elsewhere, still occupy some wetlands and the last few decades, grassland nesting birds permanent streams. Additional surveys will have shown consistently steeper population likely reveal the presence of other vertebrate declines over a wider geographic area than any species, especially amphibians, reptiles, and other group of North American bird species small mammals, of conservation concern in (Knopf 1994), and this alarming trend has been Montana. -

Daa/,Ii.,Tionalized City and the Outlet Later Prussia Gained Possession of It

mmszm r 3?jyzpir7?oa^r (; Endorsed bu the Mississippi Valley Association as a Part of One of Danzig’s Finest Streets. “One of the Biooest Economic union oy tup peace inranon or inuepenacnee, Danzig was treaty becomes an interna- separated from Poland and ‘21 years Moves Ever Launched on the Daa/,ii.,tionalized city and the outlet later Prussia gained possession of it. for Poland to the Baltic, is Again made a free city by Napoleon, American Continent” * * thus described In a bulletin issued by it passed once more to Poland; then the National Geographic society: back to Prussia in 1814. Picture n far north Venice, cut Danzig became the capital of West HE Mississippi Valley associa- through with streams and canals, Prussia. Government and private tion indorses the plan to estab- equipped also with a sort of irrigation docks were located there. Shipbuild- lish the Mlssi- sippi Valley Na- system to tlood the country for miles ing and the making of munitions were tional park along the Mississip- about, not for cultivation but for de- introduced and amber, beer and liquors a of were other Its pi river near McGregor, la., and fense; city typical Philadelphia products. granarict, and Prairie du Chien, Wls." streets, only with those long rows of built on an island, were erected when made of and it was the This action was taken at the stoops stone highly deco- principal grain shipping rated and into the for Poland and Silesia. first annual meeting of the Mis- jutting roadway in- port stead of on the and is a little farther rail sissippi Valley association in sidewalks, you Danzig by catch but a of the northeast of Berlin than Boston Is Chicago. -

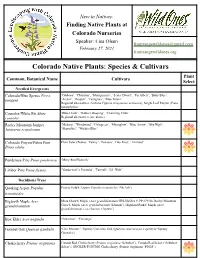

Finding Native Plants at Colorado Nurseries Speaker: Lisa Olsen [email protected] February 27, 2021 Frontrangewildones.Org

New to Natives: Finding Native Plants at Colorado Nurseries Speaker: Lisa Olsen [email protected] February 27, 2021 frontrangewildones.org Colorado Native Plants: Species & Cultivars Plant Common, Botanical Name Cultivars Select Needled Evergreens Colorado/Blue Spruce Picea ‘Globosa’, ‘Christina’, ‘Montgomery’, ‘Sester Dwarf’, ‘Fat Albert’, ‘Baby Blue’, pungens ‘Avatar’, ‘Hoopsii’, ‘Fastigiata’, ‘Blue Totem’ Regional alternatives: Arizona Cypress (Cupressus arizonica), Single Leaf Pinyon (Pinus monophylla) Concolor/White Fir Abies ‘Blue Cloak’, ‘Gable’s Weeping’, ‘Charming Chub’ concolor Regional alternatives (see above) Rocky Mountain Juniper ‘Medora’, ‘Woodward’, ‘Cologreen’, ‘Moonglow’, ‘Blue Arrow’, ‘Sky High’, Juniperus scopulorum ‘Skyrocket’, ‘Wichita Blue’ Colorado Pinyon/Piñon Pine Plant Select Petites: ‘Farmy’, ‘Penasco’, Tiny Pout’, ‘Trinidad’ Pinus edulis Ponderosa Pine Pinus ponderosa ‘Mary Ann Heacock’ Limber Pine Pinus flexilis ‘Vanderwolf’s Pyramid’, 'Tarryall', ‘Lil’ Wolf’ Deciduous Trees Quaking Aspen Populus Prairie Gold® Aspen (Populus tremuloides ‘NE Arb’) tremuloides Bigtooth Maple Acer Mesa Glow® Maple (Acer grandidentatum 'JFS-NuMex 3' PP 27930), Rocky Mountain grandidentatum Glow® Maple (Acer grandidentatum 'Schmidt'), Highland Park® Maple (Acer grandidentatum x saccharum ‘Hipzam’) Box Elder Acer negundo ‘Sensation’, ‘Flamingo’ Gambel Oak Quercus gambelii ‘Gila Monster’, 'Speedy Gonzales' Oak (Quercus macrocarpa x gambelii 'Speedy Gonzales') Chokecherry Prunus virginiana Canada Red Chokecherry (Prunus