Costs and Returns of the Crop-Cattle System in the Western Province Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Living in a Global Commons – the Case of Residents of a National Park in the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (Kaza TFCA), Southern Africa

Living in a Global Commons – the case of residents of a national park in the Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KaZa TFCA), southern Africa. Author: C A Murphy 1 “The empowering of local communities will not be enough to ensure the functioning of large Transboundary Natural Resource Management Areas. The sheer scale of such a venture is so large that, after achieving empowerment, it will be necessary to develop new institutions that enable a mosaic of communities to represent themselves in the higher decision taking forums and to co-ordinate their ecological management across a wide landscape. This requires both delegation of some authority upwards and a strong degree of accountability downward (Murphree, 2000 ). ABSTRACT In 2006, five southern African countries pledged their support for the establishment of the Kavango-Zambezi Tranfrontier Conservation Area, also known as the KaZa TFCA. The driver behind this global commons is that it houses the largest population of African elephant left in the world. Sioma Ngweze National Park lies in the far-flung south-west corner of Zambia and is the least developed park in Zambia. Yet from a global commons perspective, it forms the geographic heart of the KaZa TFCA and is a corridor for elephants moving from Botswana into Zambia and Angola. International transboundary NGOs (Peace Parks Foundation and Conservation International) have recently taken a keen interest in the Park’s status. As a result of the Park being inhabited, there is an overlay of three institutions operating – an ancient traditional authority, a local government authority (District Commissioner and councillors), with the wildlife authorities being a relative newcomer. -

CHIEFS and the STATE in INDEPENDENT ZAMBIA Exploring the Zambian National Press

CHIEFS AND THE STATE IN INDEPENDENT ZAMBIA Exploring the Zambian National Press •J te /V/- /. 07 r s/ . j> Wim van Binsbergen Introduction In West African countries such as Nigeria, Ghana and Sierra Leone, chiefs have successfully entered the modern age, characterized by the independent state and its bureaucratie institutions, peripheral capitalism and a world-wide electronic mass culture. There, chiefs are more or less conspicuous both in daily life, in post-Independence literary products and even in scholarly analysis. In the first analysis, the Zambian situation appears to be very different. After the späte of anthropological research on chiefs in the colonial era,1 post-Independence historical research has added précision and depth to the scholarly insight concerning colonial chiefs and the precolonial rulers whose royal or aristocratie titles the former had inherited, as well as those (few) cases where colonial chieftaincies had been downright invented for the sake of con- venience and of systemic consistence all over the territory of the then Northern Rhodesia. But precious little has been written on the rôle and performance of Zambian chiefs öfter Independence. A few recent regional studies offer useful glances at chiefly affairs in 1. The colonial anthropological contribution to the study of Zambian chieftainship centered on, the Rhodes-Livingstone Institute and the Manchester School, and included such classic studies of chieftainship as Barnes 1954; Cunnison 1959; Gluckman 1943, 1967; Richards 1935; Watson 1958. Cf. Werbner 1984 for a recent appraisal. e Copyright 1987 - Wim van Binsbergen - 139 - CHIEFS IN INDEPENDENT ZAMBIA Wim van Binsbergen selected rural districts,2 but by and large they fail to make the link with the national level they concentrât« on the limited number of chiefs of the région under study. -

Determinants of Spatio Temporal Variability of Water Quality in The

© University of Hamburg 2018 All rights reserved Klaus Hess Publishers Göttingen & Windhoek www.k-hess-verlag.de ISBN: 978-3-933117-95-3 (Germany), 978-99916-57-43-1 (Namibia) Language editing: Will Simonson (Cambridge), and Proofreading Pal Translation of abstracts to Portuguese: Ana Filipa Guerra Silva Gomes da Piedade Page desing & layout: Marit Arnold, Klaus A. Hess, Ria Henning-Lohmann Cover photographs: front: Thunderstorm approaching a village on the Angolan Central Plateau (Rasmus Revermann) back: Fire in the miombo woodlands, Zambia (David Parduhn) Cover Design: Ria Henning-Lohmann ISSN 1613-9801 Printed in Germany Suggestion for citations: Volume: Revermann, R., Krewenka, K.M., Schmiedel, U., Olwoch, J.M., Helmschrot, J. & Jürgens, N. (eds.) (2018) Climate change and adaptive land management in southern Africa – assessments, changes, challenges, and solutions. Biodiversity & Ecology, 6, Klaus Hess Publishers, Göttingen & Windhoek. Articles (example): Archer, E., Engelbrecht, F., Hänsler, A., Landman, W., Tadross, M. & Helmschrot, J. (2018) Seasonal prediction and regional climate projections for southern Africa. In: Climate change and adaptive land management in southern Africa – assessments, changes, challenges, and solutions (ed. by Revermann, R., Krewenka, K.M., Schmiedel, U., Olwoch, J.M., Helmschrot, J. & Jürgens, N.), pp. 14–21, Biodiversity & Ecology, 6, Klaus Hess Publishers, Göttingen & Windhoek. Corrections brought to our attention will be published at the following location: http://www.biodiversity-plants.de/biodivers_ecol/biodivers_ecol.php Biodiversity & Ecology Journal of the Division Biodiversity, Evolution and Ecology of Plants, Institute for Plant Science and Microbiology, University of Hamburg Volume 6: Climate change and adaptive land management in southern Africa Assessments, changes, challenges, and solutions Edited by Rasmus Revermann1, Kristin M. -

ZAMBIAN COUNTRY REPORT TOWARDS Sowangr

MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND CO-OPERATIVES DEPARTMENT OF VETERINARY SERVICES AND LIVESTOCK DEVELOPMENT REPORT ON THE STATE OF ANIMAL GENETIC RESOURCES IN ZAMBIA A CONTRIBUTION TO THE FIRST REPORT ON THE WORLD’S ANIMAL GENETIC RESOURCES ZAMBIA FAnGR NATIONAL FOCAL POINT MAZABUKA EMAIL: [email protected] [email protected] NOVEMBER, 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Table of Contents i Acronyms used vi List of Tables viii Preface ix Acknowledgement x Chapter one 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Physiographic and Climatic Features 1 1.1.1 Climate 1 1.1.2 Human Population 1 1.2 Agro-Ecological Zones (Regions) 2 1.3.1 Forest Types 3 1.3.2 Agricultural Sector 4 1.3.3 Livestock Population 4 1.3.4 Livestock Enterprises 4 1.3.5 Supply of Genetic Materials 6 1.4.3.1 Local Source 6 1.4.3.2 Imported Genetic Materials 6 1.4.4 Trends in Livestock Production 7 1.5 Food Security 7 1.6 Human Population Trends 8 1.7 Role of Livestock 9 Chapter Two 2.0 The State of Animal Production Systems 10 2.1 Main Animal Production Systems in Zambia 10 i 2.1.1 The Traditional Production System 10 2.1.2 The Medium Scale Commercial Production System 10 2.1.3 The Large Scale Commercial Production System 11 2.2 The Most Important Animal Products and By-Products in Zambia 11 2.2.1 Poultry 12 2.2.2 Pigs 12 2.2.3 Sheep and Goats 12 2.2.4 Cattle 12 2.3 Major Trends and Significant Changes in the Use and Management of AnGR in Zambia 13 Chapter Three 3.0 The State of Livestock Genetic Diversity in Zambia 14 3.1 Locally Adapted Cattle Breeds 15 3.2 Recently Introduced Cattle Breeds 22 3.3 Continually -

Barotse Floodplain

Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA DETAILED ASSESSMENT, CONCEPTUAL DESIGN AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) STUDY Public Disclosure Authorized FOR THE IMPROVED USE OF PRIORITY TRADITIONAL CANALS IN THE BAROTSE SUB-BASIN OF THE ZAMBEZI ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT Public Disclosure Authorized ASSESSMENT Final Report October 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized 15 juillet 2004 BRL ingénierie 1105 Av Pierre Mendès-France BP 94001 30001 Nîmes Cedex5 France NIRAS 4128 , Mwinilunga Road, Sunningdale, Zambia Date July 23rd, 2014 Contact Eric Deneut Document title Environmental and Social Impact Assessment for the improved use of priority canals in the Barotse Sub-Basin of the Zambezi Document reference 800568 Code V.3 Date Code Observation Written by Validated by May 2014 V.1 Eric Deneut: ESIA July 2014 V.2 montage, Environmental baseline and impact assessment Charles Kapekele Chileya: Social Eric Verlinden October 2014 V.3 baseline and impact assessment Christophe Nativel: support in social baseline report ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR THE IMPROVED USE OF PRIORITY TRADITIONAL CANALS IN THE BAROTSE SUB-BASIN OF THE ZAMBEZI Table of content 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 2 1.1 Background of the project 2 1.2 Summary description of the project including project rationale 6 1.2.1 Project rationale 6 1.2.2 Summary description of works 6 1.3 Objectives the project 7 1.3.1 Objectives of the Assignment 8 1.3.2 Objective of the ESIA 8 1.4 Brief description of the location 10 1.5 Particulars of Shareholders/Directors 10 1.6 Percentage of shareholding by each shareholder 10 1.7 The developer’s physical address and the contact person and his/her details 10 1.8 Track Record/Previous Experience of Enterprise Elsewhere 11 1.9 Total Project Cost/Investment 11 1.10 Proposed Project Implementation Date 12 2. -

Report of the Committee on Communications, Transport, Works and Supply for the Second Session of the Eleventh National Assembly Appointed on 26Th September 2012

REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON COMMUNICATIONS, TRANSPORT, WORKS AND SUPPLY FOR THE SECOND SESSION OF THE ELEVENTH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY APPOINTED ON 26TH SEPTEMBER 2012 Consisting of: Mr K Simbao, MP (Chairperson); Mr W Banda, MP; Mr L Chabala, MP; Mr M Chishimba, MP; Mrs A M Chungu, MP; Mr K Konga, MP; Mr V M Mooya, MP; and Mr O C Mulomba, MP. The Honourable Mr Speaker National Assembly Parliament Buildings LUSAKA Sir Your Committee has the honour to present its report for the Second Session of the Eleventh National Assembly. Functions of the Committee 2. In accordance with the National Assembly Standing Orders, the functions of your Committee are to: a. study and report on the mandate, management and operations of the Ministry of Transport, Works, Supply and Communications and carry out any other duties assigned or referred to them by the house pertaining to the activities of the said Ministry; b. carry out detailed investigations or scrutiny of certain activities being undertaken by the Ministry and make appropriate recommendations to the House through reports; and c. consider in detail the annual reports of the agencies and/or departments under the Ministry of Transport, Works, Supply and Communications; and consider any Bills that may be referred to it by the House. Meetings of the Committee 3. Your Committee held sixteen meetings during the year under review. Procedure adopted by your Committee 4. In order to gain insight on the topical issue, your Committee interacted with the following stakeholders: (i) National Airports Corporation Limited; (ii) Zambia Chamber of Commerce and Industry; (iii) Board of Airlines Representatives of Zambia; (iv) Engineering Institution of Zambia; (v) National Council for Construction; (vi) Guild Air-Traffic Controllers of Zambia; (vii) Newrest First Catering Limited; (viii) Dr Chabula J. -

Republic of Zambia Second National Agricultural

REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA SECOND NATIONAL AGRICULTURAL POLICY Ministry of Agriculture and Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock Independence Avenue Mulungushi House LUSAKA ZAMBIA February, 2016 National Agricultural Policy FOREWORD It is our great pleasure to present the Second National Agricultural Policy (SNAP) on behalf of the Government of the Republic of Zambia. This Policy provides policy guidelines for the development of the agriculture sector in Zambia. This Policy is the second National Agricultural Policy which has been formulated in order to take into account the current trends and issues that have emerged in the agriculture sector as well as address the challenges that were observed during implementation of the 2004-2015 National Agricultural Policy (NAP). Furthermore, the SNAP seeks to be in line with the new political environment in the country. The Policy is a product of extensive consultations between Government and other stakeholders in the agriculture sector. It encompasses key facets of the agriculture sector namely; food and nutritional security, agricultural production and productivity, agricultural diversification, agricultural research and extension services, sustainable resource use, promotion of irrigation, agro-processing and value addition, agricultural marketing and trade, livestock and fisheries development. The Institutional and legislative framework, decentralisation, private sector participation, support to co-operatives and other farmer organisations and crosscutting issues such as Gender mainstreaming, HIV and -

FLOODS GLIDE No

Appeal no. MDRZM004 ZAMBIA: FLOODS GLIDE no. FL-2007-000011-ZMB 20 March 2007 The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organization and its millions of volunteers are active in over 185 countries. In Brief THIS EMERGENCY APPEAL SEEKS CHF 798,072 (USD 654,157 OR EUR 495,696) IN CASH, KIND, OR SERVICES TO ASSIST 1,000 FAMILIES FOR SIX MONTHS CHF 54,000 was allocated from the Federation’s disaster Relief Emergency Funds (DREF) on 16 January 2007. For more details please refer to http://www.ifrc.org/docs/appeals/07/MDRZM004.pdf. <Click here to link directly to the attached Appeal budget> This operation is aligned with the International Federation's Global Agenda, which sets out four broad goals to meet the Federation's mission to "improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity". Global Agenda Goals: · Reduce the numbers of deaths, injuries and impact from disasters. · Reduce the number of deaths, illnesses and impact from diseases and public health emergencies. · Increase local community, civil society and Red Cross Red Crescent capacity to address the most urgent situations of vulnerability. · Reduce intolerance, discrimination and social exclusion and promote respect for diversity and human dignity. The situation The most frequently recurring natural disaster in Zambia is drought, but in recent years, floods have increasingly become recurrent disasters, especially along the main Zambezi river valley. In 2006, Zambia experienced floods that affected 4,000 people in Kazungula area along the Zambezi. -

Zambia's Investment

ZAMBIA’S INVESTMENT PROJECTS ZAMBIA DEVELOPMENT AGENCY Promoting Zambia’s Economic Growth and Development ZAMBIA AT A GLANCE he peaceful and democratic country of Zambia has for many years enjoyed both social and political stability as well as a healthy macroeconomic environment, with Teconomic growth averaging 6 percent per annum since 2003. Backed by rich natural resources such as copper and cobalt, the minerals sector has for many years been at the forefront of Zambia’s expanding economy. Another prominent sector of the Zambian economy is agriculture, thanks to the country’s good soil and large tracts of fertile arable land. There is also an abundant hydropower resource to be found in the numerous lakes, dams and rivers. Efforts to further diversify the economy mean that increased attention is being given to the manufacturing sector for increased value addition to mineral and agro products and the tourism sector on the backdrop of abundant wildlife, numerous waterfalls and scenic beauty having great potential for further development. Strategically Located - Land Linked Kenya South Africa 2 ZAMBIA DEVELOPMENT AGENCY AGRICULTURE SECTOR ZAMBIA DEVELOPMENT AGENCY 3 AGRICULTURE SECTOR INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES No. Project Title Project Summary Estimated Contracting Project Investment Authority Requirements/ (US$) and/ or Financing Promoter Mode 1. Farm Block The Government of the Republic of Zambia To be Ministry of Private Sector Development identified Agriculture as the Engine to determined Agriculture funding/ Programme Economic development as well as the Main by the investment stay of the Economy. In 2002 GRZ embarked type of on development and commercialization agribusiness of agriculture land as the Farm Block Development Programme (FBDP). -

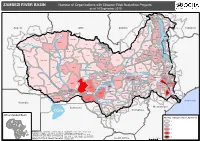

ZAMBEZI RIVER BASIN Number of Organizations with Disaster Risk Reduction Projects As at 14 September 2010

ZAMBEZI RIVER BASIN Number of Organizations with Disaster Risk Reduction Projects as at 14 September 2010 Rural Urban Mbozi Rungwe Makete Njombe Ileje Nakonde Kyela Chitipa Karonga Ludewa Isoka Songea Rural Namtumbo Angola DRC Zambia Mbinga Songea Tanzania Dala Rumphi Urban Luau Chinsali Chama Kamanongue Luakano Nkhata Bay Leua Zambezi Lake Malawi Kuemba Kameia Mwinilunga Mzimba Ilha Risunodo Likoma Sanga Mpika Lungue-Bongo Alto Zambeze Moxico Lago Solwezi Chililabombwe Chingola Lundazi Kamakupa Mufulira Kalulushi Kitwe Malawi Lufwanyama Ndola Nkhotakota Luanshya Chavuma Kasungu Lichinga Zambezi Kabompo Luangwa Serenje Ntchisi Cidade De Lichinga Masaiti Mambwe Kafue Mpongwe Chipata Dowa Kasempa Luxazes Mchinji Salima Mufumbwe Ngauma Petauke Lilongwe Kapiri Mposhi Chadiza Mkushi Katete Lumbala-Nguimbo Lukulu Dedza Nyimba Mangochi Kabwe Chifunde Angonia Lake Malombe Macanga Ntcheu Chibombo Kuito Kuanavale Shire Machinga Kalabo Kaoma Mumbwa Balaka Maravia Cuando Mongu Zumbu Tsang an o Chongwe Lusaka Zomba Luangwa Chiuta Neno Phalombe Kafue Cahora Bassa Dam Mwanza Blantyre Milange Chiradzulu Zambezi Moatize Senanga Itezhi-Tezhi Namwala Mazabuka Magoe Mulanje Angwa Cahora Bassa Thyolo Mavinga Mbire Cidade De Tete Monze Zambezi Chikwawa Siavonga Zambezi Centenary Changara Nancova Hurungwe Mt.Darwin Shang’ombo Guruve Ruya Rushinga Luenha Mutarara Sesheke Choma Gwembe Morrumbala Sanyati Nsanje Rivungo Luenha UMP Guro Ta m b a r a Kazungula Lake Kariba Kariba Musengezi Mudzi Shamva Chire Kalomo Chemba Dirico Makonde Mazowe Bindura Machile Ruenya -

The Opportunity Costs of REDD+ in Zambia

The Opportunity Costs of REDD+ in Zambia This assignment was undertaken on request by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations in Zambia under contract Number: UNJP/ZAM/068/UNJ – 09 – 12 - PHS Team Director: Saviour Chishimba Consultant: Monica Chundama Data Analyst: Akakandelwa Akakandelwa Technical Team Chithuli Makota (REDD+) Edmond Kangamugazi (Economist) Saul Banda, Jnr. (Livelihoods) Authors: Saviour Chishimba (Lead Author) Monica Chundama Akakandelwa Akakandelwa Citation: Chishimba, S., Chundama, M. & Akakandelwa, A. (2013). The Opportunity Costs of REDD+ in Zambia. The views expressed in this document are not of the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, but of the consulting firm. The Opportunity Costs of REDD+ in Zambia FINAL REPORT Saviour Chishimba (Lead Author) Monica Chundama Akakandelwa Akakandelwa 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The directors and staff of Even Ha’Ezer Consult Limited are indebted to Mr. Deuteronomy Kasaro and Mrs Maurine Mwale of the Forestry Department and Dr. Julian Fox and Ms. Celestina Lwatula of the UN-REDD Programme at FAO for providing the necessary logistical support, without which, the assignment would not have been completed. Saviour Chishimba Chief Executive Officer Even Ha’Ezer Consult Limited EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION Preserving forests entails foregoing the benefits that would have been generated by alternative deforesting and forest degrading land uses (for example agriculture, charcoal burning, etc). The difference between the benefits provided by the forest and those that would have been provided by the alternative land use is the opportunity cost of avoiding deforestation and forest degradation. Foregoing the economic benefits that come with deforestation and forest degradation will only make sense to policy makers and the general population if alternatives that are advanced under REDD+ offer sufficient sustainable benefits. -

REPORT for LOCAL GOVERNANCE.Pdf

REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON LOCAL GOVERNANCE, HOUSING AND CHIEFS’ AFFAIRS FOR THE FIFTH SESSION OF THE NINTH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY APPOINTED ON 19TH JANUARY 2006 PRINTED BY THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF ZAMBIA i REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON LOCAL GOVERNANCE, HOUSING AND CHIEFS’ AFFAIRS FOR THE FIFTH SESSION OF THE NINTH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY APPOINTED ON 19TH JANUARY 2006 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ITEMS PAGE 1. Membership 1 2. Functions 1 3. Meetings 1 PART I 4. CONSIDERATION OF THE 2006 REPORT OF THE HON MINISTER OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND HOUSING ON AUDITED ACCOUNTS OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT i) Chibombo District Council 1 ii) Luangwa District Council 2 iii) Chililabombwe Municipal Council 3 iv) Livingstone City Council 4 v) Mungwi District Council 6 vi) Solwezi Municipal Council 7 vii) Chienge District Council 8 viii) Kaoma District Council 9 ix) Mkushi District Council 9 5 SUBMISSION BY THE PERMANENT SECRETARY (BEA), MINISTRY OF FINANCE AND NATIONAL PLANNING ON FISCAL DECENTRALISATION 10 6. SUBMISSION BY THE PERMANENT SECRETARY, MINISTRY OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND HOUSING ON GENERAL ISSUES 12 PART II 7. ACTION-TAKEN REPORT ON THE COMMITTEE’S REPORT FOR 2005 i) Mpika District Council 14 ii) Chipata Municipal Council 14 iii) Katete District Council 15 iv) Sesheke District Council 15 v) Petauke District Council 16 vi) Kabwe Municipal Council 16 vii) Monze District Council 16 viii) Nyimba District Council 17 ix) Mambwe District Council 17 x) Chama District Council 18 xi) Inspection Audit Report for 1st January to 31st August 2004 18 xii) Siavonga District Council 18 iii xiii) Mazabuka Municipal Council 19 xiv) Kabompo District Council 19 xv) Decentralisation Policy 19 xvi) Policy issues affecting operations of Local Authorities 21 xvii) Minister’s Report on Audited Accounts for 2005 22 PART III 8.