Major-General Sir John Gellibrand DSO.CB.KCB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major General James Harold CANNAN CB, CMG, DSO, VD

Major General James Harold CANNAN CB, CMG, DSO, VD [1882 – 1976] Major General Cannan is distinguished by his service in the Militia, as a senior officer in World War 1 and as the Australian Army’s Quartermaster General in World War 2. Major General James Harold Cannan, CB, CMG, DSO, VD (29 August 1882 – 23 May 1976) was a Queenslander by birth and a long-term member of the United Service Club. He rose to brigadier general in the Great War and served as the Australian Army’s Quartermaster General during the Second World War after which it was said that his contribution to the defence of Australia was immense; his responsibility for supply, transport and works, a giant-sized burden; his acknowledgement—nil. We thank the History Interest Group and other volunteers who have researched and prepared these Notes. The series will be progressively expanded and developed. They are intended as casual reading for the benefit of Members, who are encouraged to advise of any inaccuracies in the material. Please do not reproduce them or distribute them outside of the Club membership. File: HIG/Biographies/Cannan Page 1 Cannan was appointed Commanding Officer of the 15th Battalion in 1914 and landed with it at ANZAC Cove on the evening of 25 April 1915. The 15th Infantry Battalion later defended Quinn's Post, one of the most exposed parts of the Anzac perimeter, with Cannan as post commander. On the Western Front, Cannan was CO of 15th Battalion at the Battle of Pozières and Battle of Mouquet Farm. He later commanded 11th Brigade at the Battle of Messines and the Battle of Broodseinde in 1917, and the Battle of Hamel and during the Hundred Days Offensive in 1918. -

RUSI of NSW Paper

Jump TO Article The article on the pages below is reprinted by permission from United Service (the journal of the Royal United Services Institute of New South Wales), which seeks to inform the defence and security debate in Australia and to bring an Australian perspective to that debate internationally. The Royal United Services Institute of New South Wales (RUSI NSW) has been promoting informed debate on defence and security issues since 1888. To receive quarterly copies of United Service and to obtain other significant benefits of RUSI NSW membership, please see our online Membership page: www.rusinsw.org.au/Membership Jump TO Article INSTITUTE PROCEEDINGS The Australian Army’s 2nd Division: an update1 an address to the Institute on 24 September 2013 by Brigadier Peter Clay, CSC Deputy Commander 2nd Division, on behalf of Major General S. L. Smith, AM, CSC, RFD Commander 2nd Division Vice-Patron, Royal United Services Institute, New South Wales Brigadier Clay details how the Australian Army’s 2nd Division, which contains most of the Australian Army Reserve, has progressed in achieving its force modernisation challenges under Army’s Plan Beersheba and outlines the delivery of a multi-role Reserve battle group for Army by the year 2015. Key words: Plan Beersheba, Total Force, Multi-role Reserve Battle Group, Exercise Hamel/Talisman Sabre, Army Reserve. On behalf of Commander 2nd Division, Major General very little change to their respective organisational Steve Smith, in this paper I will provide an update on the manning, with the exception of 11th Brigade, which has Division’s progress in integrating into the Army’s ‘Total inherited the vast majority of 7th Brigade’s Reserve assets Force’1 under Plan Beersheba2. -

10Th Battalion (Australia)

Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Wikipedia Participate in an international science photo competition! Main page Contents 10th Battalion (Australia) Featured content Current events From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Random article Donate to Wikipedia For other uses, see 2/10th Battalion (Australia). Wikipedia store The 10th Battalion was an infantry battalion of the Australian Army that served as 10th Battalion part of the all-volunteer Australian Imperial Force during World War I. Among the first Interaction units raised in Australia during the war, the battalion was recruited from South Help About Wikipedia Australia in August 1914 and formed part of the 3rd Brigade, 1st Division. After basic Community portal training, the battalion embarked for Egypt where further training was undertaken until Recent changes the battalion was committed to the Gallipoli campaign. During the landing at Anzac Contact page Cove, it came ashore as part of the initial covering force. Members of the 10th Battalion penetrated the furthest inland of any Australian troops during the initial Tools fighting, before the Allied advance inland was checked. After this, the battalion What links here helped defend the beachhead against a heavy counter-attack in May, before joining Lines of the 9th and 10th Battalions at Mena Camp, Related changes Egypt, December 1914, looking towards the pyramids. the failed August Offensive. Casualties were heavy throughout the campaign and in Upload file The soldier in the foreground is playing with a Special pages November 1915, the surviving members were withdrawn from the peninsula. In early kangaroo, the regimental mascot Permanent link 1916, the battalion was reorganised in Egypt at which time it provided a cadre staff Active 1914–1919 Page information to the newly formed 50th Battalion. -

CHAPTER XXII on Their Return to Egypt the Australian Formations Were Sent to the Suez Canal Zone and Helped to Form There A

CHAPTER XXII EGYPT : REORGANISATION OF THE A.I.F. ON their return to Egypt the Australian formations were sent to the Suez Canal zone and helped to form there a new defensive front for Egypt. Simultaneously with this service the force was reorganised : the infantry into five divisions, forming, with the New Zealand Division, two army corps destined for the Western Front ; the light horse into the Anzac Mounted Division and other mounted units which became part of a British force which fought for the rest of the war in Egypt, Sinai, and Palestine. The self-government of the force in all matters of internal administration was established, though not yet entirely recognised by all the authorities that dealt with it; in the medical service the new director, his powers being now confirmed by the Commonwealth Govern- ment but not fully admitted by the War Office, collected the new medical staff of the A.I.F., hastened clearance to Australia, finalised reforms in the dental and nursing services, and carried out in the A.A.M.C. units a reorganisation, which embodied several experiments of interest. * * 8 The closing of the Gallipoli campaign opened for the A.I.F. a new phase in its history, with service in a much wider and more diversified sphere of action. The next Return to three months were occupied in a complete Eemt reconstruction and reorganisation of the force, carried out while the troops were taking their part in the dispositions for the new strategic situation. The mise-en-scine of the reorganisation was the neighbourhood of the Suez Canal. -

Your Presentation Is the Keynote Presentation for the Block

1984 RUSI VIC BLAMEY ORATION By Major General Ken G. Cooke, ED There must be something special about a man who on the centenary of his birth and thirty-three years after his death can still trigger a gathering of so many people, including so many busy and distinguished people, in a Melbourne park on a Tuesday morning in January. So let us take a few minutes to review briefly the life of Thomas Alfred Blamey to try and determine just how this can be. He was born on 24th January, 1884 on the outskirts of Wagga Wagga, the seventh of the ten children of Richard and Margaret Blamey. His father had tried his luck at farming, both in Queensland and New South Wales, but as was often the case the ventures ended in disaster due to the old traditional enemies of drought, bush fire and fluctuating cattle prices. He then settled in Wagga where he earned his living as a contract drover. His was a pioneer family so typical of the time and it exemplified the strength of our immigrant stock both before and since. Young Tom was educated in Wagga, first at the Government school and then for the last two years at the Grammar school to which he won a place on his pure ability. His upbringing generally was as you would expect. He had to help around the family property before and after school and on vacations he worked as a tar- boy in the local shearing sheds. As he grew older he went on several droving trips to help his father. -

Chapter Xi1 Australia Doubles the A.I.F

CHAPTER XI1 AUSTRALIA DOUBLES THE A.I.F. THEAustralians and New Zealanders who returned from Gallipoli to Egypt were a different force from the adven- turous body that had left Egypt eight months before. They were a military force with strongly established, definite traditions. Not for anything, if he could avoid it, would an Australian now change his loose, faded tu& or battered hat for the smartest cloth or headgear of any other army. Men clung to their Australian uniforms till they were tattered to the limit of decency. Each of the regimental numbers which eight months before had been merely numbers, now carried a poignant meaning for every man serving with the A.I.F., and to some extent even for the nation far away in Australia. The ist, 2nd, 3rd and 4th Infantry Battalions-they had rushed Lone Pine; the 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th had made that swift advance at Helles; the gth, ioth, I ith, 12th had stormed the Anzac heights; the igth, iqth, igth, 16th had first held Quinn’s, Courtney’s and Pope’s; the battalion numbers of the 2nd Division were becoming equally famous-and so with the light horse, artillery, engineers, field ambulances, transport companies, and casualty clearing stations. Service on the Gallipoli beaches had given a fighting record even to British, Egyptian and Maltese labour units that normally would have served far behind the front. The troops from Gallipoli were urgently desired by Kitchener for the defence of Egypt against the Turkish expedition that threatened to descend on it as soon as the Allies’ evacuation had released the Turkish army ANZAC TO AMIENS [Dec. -

'Feed the Troops on Victory': a Study of the Australian

‘FEED THE TROOPS ON VICTORY’: A STUDY OF THE AUSTRALIAN CORPS AND ITS OPERATIONS DURING AUGUST AND SEPTEMBER 1918. RICHARD MONTAGU STOBO Thesis prepared in requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences University of New South Wales, Canberra June 2020 Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname/Family Name : Stobo Given Name/s : Richard Montagu Abbreviation for degree as given in the : PhD University calendar Faculty : History School : Humanities and Social Sciences ‘Feed the Troops on Victory’: A Study of the Australian Corps Thesis Title : and its Operations During August and September 1918. Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) This thesis examines reasons for the success of the Australian Corps in August and September 1918, its final two months in the line on the Western Front. For more than a century, the Corps’ achievements during that time have been used to reinforce a cherished belief in national military exceptionalism by highlighting the exploits and extraordinary fighting ability of the Australian infantrymen, and the modern progressive tactical approach of their native-born commander, Lieutenant-General Sir John Monash. This study re-evaluates the Corps’ performance by examining it at a more comprehensive and granular operational level than has hitherto been the case. What emerges is a complex picture of impressive battlefield success despite significant internal difficulties that stemmed from the particularly strenuous nature of the advance and a desperate shortage of manpower. These played out in chronic levels of exhaustion, absenteeism and ill-discipline within the ranks, and threatened to undermine the Corps’ combat capability. In order to reconcile this paradox, the thesis locates the Corps’ performance within the wider context of the British army and its operational organisation in 1918. -

Tom Gellibrand Was Born at Nuwara Iliya in Ceylon Now Sri Lanka On

OBITUARY THOMAS IANSON GELLIBRAND Tom Gellibrand was born at Nuwara Iliya in Ceylon now tion at the Hobart Congress in 1964 that the collecting Sri Lanka on November 29, 1908. His father was a cap- of birds or their eggs within the area specified for a Con- tain in the British Army and he retired in 1912 and gress shall not be permitted was seconded by Noel Jack brought the family to Tasmania where two of his brothers of Queensland and carried. Tom died in Tasmania on were running the family property Cleveland at Ouse. He November 15, 1981. bought an apple orchard and just one year later the First World War started and he joined the A.I.F. Tom then The name Gellibrand is well-known in Victoria. Tom's aged five had a daily tutor and later went to Hutchen's great-grandfather Joseph Tice Gellibrand was appointed School in Hobart and finally to Geelong Grammar. His the first Attorney General for Tasmania in 1824 and he great interest was farming particularly in sheep and he was behind the move to send John Batman to start a set- was a jackaroo on Western Victorian properties and he tlement in Victoria. It was on a visit to Melbourne in 1837 also took a course on wool-classing at the Geelong that he with Mr Hesse whilst visiting settlers of the Port Gordon Institute. Whilst he was farming at Murrindindi Phillip Association became lost in the Otways and search in north-east Victoria he joined and was commissioned parties failed to find them or their horses. -

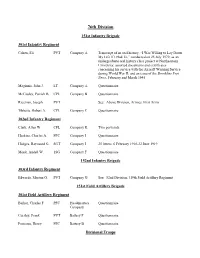

2Nd Division, 319Th Field Artillery Regiment

76th Division 151st Infantry Brigade 301st Infantry Regiment Cohen, Eli PVT Company A Transcript of an oral history, “I Was Willing to Lay Down My Life If I Had To,” conducted on 25 July 1979, as an undergraduate oral history class project at Northeastern University; assorted documents and certificates concerning his service with the Aircraft Warning Service during World War II; and an issue of the Brookline Post News, February and March 1945 Maginnis, John J. LT Company A Questionnaire McCauley, Patrick B. CPL Company B Questionnaire Riceman, Joseph PVT See: Above Division, Armies, First Army Tibbetts, Robert A. CPL Company C Questionnaire 302nd Infantry Regiment Clark, Allen W. CPL Company K Two postcards Haskins, Charles A. PFC Company I Questionnaire Hodges, Raymond G. SGT Company I 25 letters, 6 February 1918-22 June 1919 Monk, Audell W. 1SG Company F Questionnaire 152nd Infantry Brigade 303rd Infantry Regiment Edwards, Morton G. PVT Company G See: 82nd Division, 319th Field Artillery Regiment 151st Field Artillery Brigade 301st Field Artillery Regiment Barker, Charles F. PFC Headquarters Questionnaire Company Cursley, Frank PVT Battery F Questionnaire Porteous, Henry PFC Battery B Questionnaire Divisional Troops 301st Machine Gun Battalion Malloy, Harry D. CPL Questionnaire 301st Engineer Regiment Benedict, Eric G. CPT Company A Scrapbook, February 1917-1919, containing photo-graphs, newspaper clippings, official documents, and assorted materials; unit history, Short History of the 301st Engineers; typed “Historical Report, Company G, Fifty- Sixth U.S. Engineers (Searchlight),” November 1918; typed “Anti-Aircraft Defences of Colombey-les-Belles,” November 1918; roster of Company G, 56th Engineer Regiment; shipping and landing lists, Company D, 604th Engineer Regiment; newspaper article on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Boston Evening Transcript, 11 November 1931; and Questionnaire [Short History transferred to Library holdings] Borod, Esmond S. -

The New Zealand Army Officer Corps, 1909-1945

1 A New Zealand Style of Military Leadership? Battalion and Regimental Combat Officers of the New Zealand Expeditionary Forces of the First and Second World Wars A thesis provided in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History at the University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand Wayne Stack 2014 2 Abstract This thesis examines the origins, selection process, training, promotion and general performance, at battalion and regimental level, of combat officers of the New Zealand Expeditionary Forces of the First and Second World Wars. These were easily the greatest armed conflicts in the country’s history. Through a prosopographical analysis of data obtained from personnel records and established databases, along with evidence from diaries, letters, biographies and interviews, comparisons are made not only between the experiences of those New Zealand officers who served in the Great War and those who served in the Second World War, but also with the officers of other British Empire forces. During both wars New Zealand soldiers were generally led by competent and capable combat officers at all levels of command, from leading a platoon or troop through to command of a whole battalion or regiment. What makes this so remarkable was that the majority of these officers were citizen-soldiers who had mostly volunteered or had been conscripted to serve overseas. With only limited training before embarking for war, most of them became efficient and effective combat leaders through experiencing battle. Not all reached the required standard and those who did not were replaced to ensure a high level of performance was maintained within the combat units. -

THE AMIENS OFFENSIVE Major General JP Stevens AO

THE AMIENS OFFENSIVE Major General J. P. Stevens AO (Retd) The Entente launched the Amiens offensive on the 8th of August, 1918. This paper examines the actions of the Australian Corps’ artillery over the following six weeks as the Corps broke the German lines at Villers Bretonneux and then advanced for about 60 kilometres to the Hindenburg Line at Bellenglise. By way of background, in 1918 the early strategic initiative lay with Germany, which between March and June launched four offensives without achieving decisive success, although the first, discomfortingly, ended within heavy-artillery range of the important Entente rail junction of Amiens. The Battle of Hamel in this area in early July was a sign the tide was turning, but it was only when the final German offensive on the Marne failed a few weeks later that Entente leaders felt confident enough to take the initiative. They chose first to free up Amiens. Here opposite the British 4th and 1st French Armies, the German defences were temporary, improvised, lacking in depth, and manned by depleted divisions. The front passed through Morlancourt, Villers Bretonneux and Montdidier, and behind it the countryside was little touched by war until a line of 1915 trenches running from Mericourt to Harbonnieres and Le Quesnel, and, further east, substantial, overgrown trench lines from 1916 stretching from Peronne to Roye. The Somme River was a significant obstacle, especially where it ran north-south, across the line of advance around Mont St Quentin and Peronne. German forces were supplied through the rail junctions at Peronne, Chaulnes and Roye, and the Entente Armies were directed to strike in the direction of the latter. -

Military Images Index the Index Is Organized Alphabetically by Subject Followed by the Month and Year of the Issue, and the Page Number of the Article

Military Images Magazine Magazine Index Military Images Index The index is organized alphabetically by subject followed by the month and year of the issue, and the page number of the article. Please refer back to this index periodically as issues are still being added. This is an index of Civil War era photographic images only, not magazine articles. Many of the photos are owned by private collectors or descendants of those pictured. Please contact Military Images magazine directly for more information at http://militaryimagesmagazine.com. Soldiers are Privates in the Infantry unless otherwise noted. Regiments are Infantry unless otherwise noted. Abbott, Lt. Edward. 17th U.S. Jul./Aug. 1996, page 22. Abbott, Francis H. Co A, 17th Virginia. Mar./Apr. 2008, page 14. Abbott, Henry H. 7th Indiana Cav. Jul./Aug. 1985, page 25. Abbott, Lt. Lemuel. 10th Vermont. Sep./Oct. 1991, page 11. Abercrombie, Brig.Gen. John. and staff. May/Jun. 2000, page 13. Abernathy, Macon. Co G, 10th Alabama. Nov./Dec. 2005, page 24. Ackerman, Andrew W. 11th New Jersey. Nov./Dec. 2003, page 21. Ackles, Lt. George. unknown. Jul./Aug. 1992, page 18. Acton, Capt. Frank. Co F, 12th New Jersey. Sep./Oct. 1989, page 21. Adair, William Penn. 2nd Cherokee Mounted Rifles. C.S.A. Sep./Oct. 1994, page 11. Adams, 1stLt. Allen. 21st New York. Nov./Dec. 1987, page 25; Nov./Dec. 1999, page 47. Adams, Charles Francis. 1st & 5th Massachusetts Cav. Sep./Oct. 2007, page 28. Adams, George. 6th New York Hy. Art. Winter 2015, page 44. Adams, Henry M. Co F, 83rd Pennsylvania.