THE AMIENS OFFENSIVE Major General JP Stevens AO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major General James Harold CANNAN CB, CMG, DSO, VD

Major General James Harold CANNAN CB, CMG, DSO, VD [1882 – 1976] Major General Cannan is distinguished by his service in the Militia, as a senior officer in World War 1 and as the Australian Army’s Quartermaster General in World War 2. Major General James Harold Cannan, CB, CMG, DSO, VD (29 August 1882 – 23 May 1976) was a Queenslander by birth and a long-term member of the United Service Club. He rose to brigadier general in the Great War and served as the Australian Army’s Quartermaster General during the Second World War after which it was said that his contribution to the defence of Australia was immense; his responsibility for supply, transport and works, a giant-sized burden; his acknowledgement—nil. We thank the History Interest Group and other volunteers who have researched and prepared these Notes. The series will be progressively expanded and developed. They are intended as casual reading for the benefit of Members, who are encouraged to advise of any inaccuracies in the material. Please do not reproduce them or distribute them outside of the Club membership. File: HIG/Biographies/Cannan Page 1 Cannan was appointed Commanding Officer of the 15th Battalion in 1914 and landed with it at ANZAC Cove on the evening of 25 April 1915. The 15th Infantry Battalion later defended Quinn's Post, one of the most exposed parts of the Anzac perimeter, with Cannan as post commander. On the Western Front, Cannan was CO of 15th Battalion at the Battle of Pozières and Battle of Mouquet Farm. He later commanded 11th Brigade at the Battle of Messines and the Battle of Broodseinde in 1917, and the Battle of Hamel and during the Hundred Days Offensive in 1918. -

RUSI of NSW Paper

Jump TO Article The article on the pages below is reprinted by permission from United Service (the journal of the Royal United Services Institute of New South Wales), which seeks to inform the defence and security debate in Australia and to bring an Australian perspective to that debate internationally. The Royal United Services Institute of New South Wales (RUSI NSW) has been promoting informed debate on defence and security issues since 1888. To receive quarterly copies of United Service and to obtain other significant benefits of RUSI NSW membership, please see our online Membership page: www.rusinsw.org.au/Membership Jump TO Article INSTITUTE PROCEEDINGS The Australian Army’s 2nd Division: an update1 an address to the Institute on 24 September 2013 by Brigadier Peter Clay, CSC Deputy Commander 2nd Division, on behalf of Major General S. L. Smith, AM, CSC, RFD Commander 2nd Division Vice-Patron, Royal United Services Institute, New South Wales Brigadier Clay details how the Australian Army’s 2nd Division, which contains most of the Australian Army Reserve, has progressed in achieving its force modernisation challenges under Army’s Plan Beersheba and outlines the delivery of a multi-role Reserve battle group for Army by the year 2015. Key words: Plan Beersheba, Total Force, Multi-role Reserve Battle Group, Exercise Hamel/Talisman Sabre, Army Reserve. On behalf of Commander 2nd Division, Major General very little change to their respective organisational Steve Smith, in this paper I will provide an update on the manning, with the exception of 11th Brigade, which has Division’s progress in integrating into the Army’s ‘Total inherited the vast majority of 7th Brigade’s Reserve assets Force’1 under Plan Beersheba2. -

10Th Battalion (Australia)

Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Wikipedia Participate in an international science photo competition! Main page Contents 10th Battalion (Australia) Featured content Current events From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Random article Donate to Wikipedia For other uses, see 2/10th Battalion (Australia). Wikipedia store The 10th Battalion was an infantry battalion of the Australian Army that served as 10th Battalion part of the all-volunteer Australian Imperial Force during World War I. Among the first Interaction units raised in Australia during the war, the battalion was recruited from South Help About Wikipedia Australia in August 1914 and formed part of the 3rd Brigade, 1st Division. After basic Community portal training, the battalion embarked for Egypt where further training was undertaken until Recent changes the battalion was committed to the Gallipoli campaign. During the landing at Anzac Contact page Cove, it came ashore as part of the initial covering force. Members of the 10th Battalion penetrated the furthest inland of any Australian troops during the initial Tools fighting, before the Allied advance inland was checked. After this, the battalion What links here helped defend the beachhead against a heavy counter-attack in May, before joining Lines of the 9th and 10th Battalions at Mena Camp, Related changes Egypt, December 1914, looking towards the pyramids. the failed August Offensive. Casualties were heavy throughout the campaign and in Upload file The soldier in the foreground is playing with a Special pages November 1915, the surviving members were withdrawn from the peninsula. In early kangaroo, the regimental mascot Permanent link 1916, the battalion was reorganised in Egypt at which time it provided a cadre staff Active 1914–1919 Page information to the newly formed 50th Battalion. -

CHAPTER XXII on Their Return to Egypt the Australian Formations Were Sent to the Suez Canal Zone and Helped to Form There A

CHAPTER XXII EGYPT : REORGANISATION OF THE A.I.F. ON their return to Egypt the Australian formations were sent to the Suez Canal zone and helped to form there a new defensive front for Egypt. Simultaneously with this service the force was reorganised : the infantry into five divisions, forming, with the New Zealand Division, two army corps destined for the Western Front ; the light horse into the Anzac Mounted Division and other mounted units which became part of a British force which fought for the rest of the war in Egypt, Sinai, and Palestine. The self-government of the force in all matters of internal administration was established, though not yet entirely recognised by all the authorities that dealt with it; in the medical service the new director, his powers being now confirmed by the Commonwealth Govern- ment but not fully admitted by the War Office, collected the new medical staff of the A.I.F., hastened clearance to Australia, finalised reforms in the dental and nursing services, and carried out in the A.A.M.C. units a reorganisation, which embodied several experiments of interest. * * 8 The closing of the Gallipoli campaign opened for the A.I.F. a new phase in its history, with service in a much wider and more diversified sphere of action. The next Return to three months were occupied in a complete Eemt reconstruction and reorganisation of the force, carried out while the troops were taking their part in the dispositions for the new strategic situation. The mise-en-scine of the reorganisation was the neighbourhood of the Suez Canal. -

EPCI À FP D'origine Collectivité Sièges En 2016 Pop Mun2016

Future communauté de communes "Terre de Picardie" Simulation de répartition des sièges de conseillers communautaires sièges droit EPCIàFP_acronyme EPCI à FP d'origine Collectivité sièges en 2016 pop_mun2016 commun communauté de communes de Haute CCHP Picardie ABLAINCOURT PRESSOIR 1 278 1 communauté de communes de Haute CCHP Picardie ASSEVILLERS 1 286 1 CCS communauté de communes du Santerre BAYONVILLERS 1 356 1 CCS communauté de communes du Santerre BEAUFORT EN SANTERRE 1 203 1 communauté de communes de Haute CCHP Picardie BELLOY EN SANTERRE 1 160 1 communauté de communes de Haute CCHP Picardie BERNY EN SANTERRE 1 154 1 CCS communauté de communes du Santerre BOUCHOIR 1 311 1 CCS communauté de communes du Santerre CAIX 3 749 2 communauté de communes de Haute CCHP Picardie CHAULNES 8 1 975 5 CCS communauté de communes du Santerre CHILLY 1 197 1 communauté de communes de Haute CCHP Picardie CHUIGNES 1 134 1 communauté de communes de Haute DOMPIERRE CCHP 3 692 2 Picardie BECQUINCOURT communauté de communes de Haute CCHP Picardie ESTREES DENIECOURT 1 346 1 communauté de communes de Haute CCHP Picardie FAY 1 109 1 CCS communauté de communes du Santerre FOLIES 1 132 1 communauté de communes de Haute CCHP Picardie FONTAINE LES CAPPY 1 53 1 communauté de communes de Haute FOUCAUCOURT EN CCHP 1 283 1 Picardie SANTERRE CCS communauté de communes du Santerre FOUQUESCOURT 1 174 1 communauté de communes de Haute CCHP Picardie FRAMERVILLE RAINECOURT 2 480 1 CCS communauté de communes du Santerre FRANSART 1 152 1 communauté de communes de Haute CCHP -

'Feed the Troops on Victory': a Study of the Australian

‘FEED THE TROOPS ON VICTORY’: A STUDY OF THE AUSTRALIAN CORPS AND ITS OPERATIONS DURING AUGUST AND SEPTEMBER 1918. RICHARD MONTAGU STOBO Thesis prepared in requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences University of New South Wales, Canberra June 2020 Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname/Family Name : Stobo Given Name/s : Richard Montagu Abbreviation for degree as given in the : PhD University calendar Faculty : History School : Humanities and Social Sciences ‘Feed the Troops on Victory’: A Study of the Australian Corps Thesis Title : and its Operations During August and September 1918. Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) This thesis examines reasons for the success of the Australian Corps in August and September 1918, its final two months in the line on the Western Front. For more than a century, the Corps’ achievements during that time have been used to reinforce a cherished belief in national military exceptionalism by highlighting the exploits and extraordinary fighting ability of the Australian infantrymen, and the modern progressive tactical approach of their native-born commander, Lieutenant-General Sir John Monash. This study re-evaluates the Corps’ performance by examining it at a more comprehensive and granular operational level than has hitherto been the case. What emerges is a complex picture of impressive battlefield success despite significant internal difficulties that stemmed from the particularly strenuous nature of the advance and a desperate shortage of manpower. These played out in chronic levels of exhaustion, absenteeism and ill-discipline within the ranks, and threatened to undermine the Corps’ combat capability. In order to reconcile this paradox, the thesis locates the Corps’ performance within the wider context of the British army and its operational organisation in 1918. -

Rapport Signé

Enquête publique Schéma de Cohérence Territoriale du Pays Santerre Haute Somme du lundi 11 septembre au jeudi 12 octobre 2017 sur une période de 32 jours Prescrite par arrêté de Monsieur le président du Syndicat mixte du pays Santerre Haute Somme en date du 3 août 2017 Rapport d’enquête et conclusions motivées De la commission d’enquête désignée par ordonnance n° E17000100 / 80 du 22 juin 2017 de Monsieur le Président du Tribunal administratif d’Amiens. Commission d’enquête Jean-Claude HELY Président Bernard GUILBERT et Patrick BENOIT membres titulaires RAPPORT DE LA COMMISSION D’ENQUETE INDEX DES ABREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................................................... 1 1 GENERALITES CONCERNANT L’ENQUETE .................................................................................................. 3 1.1 OBJET DE L ’ENQUETE ........................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 LOCALISATION DU PROJET .................................................................................................................................... 3 1.3 CONTEXTE REGLEMENTAIRE ................................................................................................................................ 4 2 LE PROJET ........................................................................................................................................................... 4 -

2Nd Division, 319Th Field Artillery Regiment

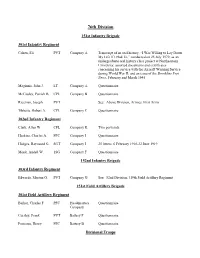

76th Division 151st Infantry Brigade 301st Infantry Regiment Cohen, Eli PVT Company A Transcript of an oral history, “I Was Willing to Lay Down My Life If I Had To,” conducted on 25 July 1979, as an undergraduate oral history class project at Northeastern University; assorted documents and certificates concerning his service with the Aircraft Warning Service during World War II; and an issue of the Brookline Post News, February and March 1945 Maginnis, John J. LT Company A Questionnaire McCauley, Patrick B. CPL Company B Questionnaire Riceman, Joseph PVT See: Above Division, Armies, First Army Tibbetts, Robert A. CPL Company C Questionnaire 302nd Infantry Regiment Clark, Allen W. CPL Company K Two postcards Haskins, Charles A. PFC Company I Questionnaire Hodges, Raymond G. SGT Company I 25 letters, 6 February 1918-22 June 1919 Monk, Audell W. 1SG Company F Questionnaire 152nd Infantry Brigade 303rd Infantry Regiment Edwards, Morton G. PVT Company G See: 82nd Division, 319th Field Artillery Regiment 151st Field Artillery Brigade 301st Field Artillery Regiment Barker, Charles F. PFC Headquarters Questionnaire Company Cursley, Frank PVT Battery F Questionnaire Porteous, Henry PFC Battery B Questionnaire Divisional Troops 301st Machine Gun Battalion Malloy, Harry D. CPL Questionnaire 301st Engineer Regiment Benedict, Eric G. CPT Company A Scrapbook, February 1917-1919, containing photo-graphs, newspaper clippings, official documents, and assorted materials; unit history, Short History of the 301st Engineers; typed “Historical Report, Company G, Fifty- Sixth U.S. Engineers (Searchlight),” November 1918; typed “Anti-Aircraft Defences of Colombey-les-Belles,” November 1918; roster of Company G, 56th Engineer Regiment; shipping and landing lists, Company D, 604th Engineer Regiment; newspaper article on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Boston Evening Transcript, 11 November 1931; and Questionnaire [Short History transferred to Library holdings] Borod, Esmond S. -

2097-3 EPCI Département De La Somme A2 Au 1Er Septembre 2020

CA DE BETHUNE-BRUAY, CA DE LENS - LIEVIN Les Etablissements Publics de Coopération Intercommunale ARTOIS LYS ROMANE Établissement public de coopération intercommunale dans le département de la Somme (80) (EPCI au 1er septembreCA D'HENIN-CARVIN 2020) CA DES DEUX BAIES CA DU DOUAISIS (CAD) EN MONTREUILLOIS (CA2BM) Communauté Urbaine Fort-Mahon- Plage CC DES 7 VALLEES Nampont Argoules Dominois Quend Villers- Communauté d’Agglomération sur-Authie Vron Ponches- Estruval Vercourt Vironchaux Regnière- Ligescourt Communauté de Communes Écluse Dompierre- Saint-Quentin- Rue Arry en-Tourmont Machy sur-Authie Machiel Bernay-en-Ponthieu Le Boisle Estrées- Bouers lès-Crécy CC DU TERNOIS Vitz-sur-Authie Le Crotoy Forest-Montiers Crécy-en-Ponthieu CC DES CAMPAGNES DE L'ARTOIS Favières Fontaine-sur-Maye Gueschart CC PONTHIEU-MARQUENTERRE Brailly- Neuilly-le-Dien Froyelles Cornehotte CU D'ARRAS Ponthoile Nouvion Noyelles- Maison- Brévillers Forest- Domvast en-Chaussée Ponthieu Frohen- Neuvillette CC OSARTIS MARQUION l'Abbaye Remaisnil Hiermont Maizicourt sur-Authie Bouquemaison Humbercourt Béalcourt Barly Lucheux Noyelles-sur-Mer Bernâtre Le Titre Lamotte- Yvrench St-Acheul Buleux Canchy Mézerolles Cayeux- Saint-Valery- Sailly- Agenvillers Yvrencheux Montigny- Grouches- sur-Mer sur-Somme Flibeaucourt Conteville les-Jongleurs Gapennes Occoches Luchuel Hautvillers- Agenville Ouville Neuilly-l'Hôpital Le Meillard Pendé Outrebois Boismont Heuzecourt Doullens Lanchères Estrébœuf Port-le-Grand Buigny- Millencourt- Cramont Prouville Hem- St-Maclou en-Ponthieu -

ANNEXE 1 DÉCOUPAGE DES SECTEURS AVEC RÉPARTITION DES COMMUNES PAR SECTEUR Secteur 1 : AUTHIE (Bassin-Versant De L’Authie Dans Le Département De La Somme)

ANNEXE 1 DÉCOUPAGE DES SECTEURS AVEC RÉPARTITION DES COMMUNES PAR SECTEUR Secteur 1 : AUTHIE (bassin-versant de l’Authie dans le département de la Somme) ACHEUX-EN-AMIENOIS 80003 LOUVENCOURT 80493 AGENVILLE 80005 LUCHEUX 80495 ARGOULES 80025 MAISON-PONTHIEU 80501 ARQUEVES 80028 MAIZICOURT 80503 AUTHEUX 80042 MARIEUX 80514 AUTHIE 80043 MEZEROLLES 80544 AUTHIEULE 80044 MONTIGNY-LES-JONGLEURS 80563 BARLY 80055 NAMPONT-SAINT-MARTIN 80580 BAYENCOURT 80057 NEUILLY-LE-DIEN 80589 BEALCOURT 80060 NEUVILLETTE 80596 BEAUQUESNE 80070 OCCOCHES 80602 BEAUVAL 80071 OUTREBOIS 80614 BERNATRE 80085 PONCHES-ESTRUVAL 80631 BERNAVILLE 80086 PROUVILLE 80642 BERTRANCOURT 80095 PUCHEVILLERS 80645 BOISBERGUES 80108 QUEND 80649 BOUFFLERS 80118 RAINCHEVAL 80659 BOUQUEMAISON 80122 REMAISNIL 80666 BREVILLERS 80140 SAINT-ACHEUL 80697 BUS-LES-ARTOIS 80153 SAINT-LEGER-LES-AUTHIE 80705 CANDAS 80168 TERRAMESNIL 80749 COIGNEUX 80201 THIEVRES 80756 COLINCAMPS 80203 VAUCHELLES-LES-AUTHIE 80777 CONTEVILLE 80208 VERCOURT 80787 COURCELLES-AU-BOIS 80217 VILLERS-SUR-AUTHIE 80806 DOMINOIS 80244 VIRONCHAUX 80808 DOMLEGER-LONGVILLERS 80245 VITZ-SUR-AUTHIE 80810 DOMPIERRE-SUR-AUTHIE 80248 VRON 80815 DOULLENS 80253 ESTREES-LES-CRECY 80290 FIENVILLERS 80310 FORT-MAHON-PLAGE 80333 FROHEN-SUR-AUTHIE 80369 GEZAINCOURT 80377 GROUCHES-LUCHUEL 80392 GUESCHART 80396 HEM-HARDINVAL 80427 HEUZECOURT 80439 HIERMONT 80440 HUMBERCOURT 80445 LE BOISLE 80109 LE MEILLARD 80526 LEALVILLERS 80470 LIGESCOURT 80477 LONGUEVILLETTE 80491 Secteur 2 : MAYE (bassin-versant de la Maye) ARRY 80030 BERNAY-EN-PONTHIEU -

Military Images Index the Index Is Organized Alphabetically by Subject Followed by the Month and Year of the Issue, and the Page Number of the Article

Military Images Magazine Magazine Index Military Images Index The index is organized alphabetically by subject followed by the month and year of the issue, and the page number of the article. Please refer back to this index periodically as issues are still being added. This is an index of Civil War era photographic images only, not magazine articles. Many of the photos are owned by private collectors or descendants of those pictured. Please contact Military Images magazine directly for more information at http://militaryimagesmagazine.com. Soldiers are Privates in the Infantry unless otherwise noted. Regiments are Infantry unless otherwise noted. Abbott, Lt. Edward. 17th U.S. Jul./Aug. 1996, page 22. Abbott, Francis H. Co A, 17th Virginia. Mar./Apr. 2008, page 14. Abbott, Henry H. 7th Indiana Cav. Jul./Aug. 1985, page 25. Abbott, Lt. Lemuel. 10th Vermont. Sep./Oct. 1991, page 11. Abercrombie, Brig.Gen. John. and staff. May/Jun. 2000, page 13. Abernathy, Macon. Co G, 10th Alabama. Nov./Dec. 2005, page 24. Ackerman, Andrew W. 11th New Jersey. Nov./Dec. 2003, page 21. Ackles, Lt. George. unknown. Jul./Aug. 1992, page 18. Acton, Capt. Frank. Co F, 12th New Jersey. Sep./Oct. 1989, page 21. Adair, William Penn. 2nd Cherokee Mounted Rifles. C.S.A. Sep./Oct. 1994, page 11. Adams, 1stLt. Allen. 21st New York. Nov./Dec. 1987, page 25; Nov./Dec. 1999, page 47. Adams, Charles Francis. 1st & 5th Massachusetts Cav. Sep./Oct. 2007, page 28. Adams, George. 6th New York Hy. Art. Winter 2015, page 44. Adams, Henry M. Co F, 83rd Pennsylvania. -

Understanding the First AIF: a Brief Guide

Last updated August 2021 Understanding the First AIF: A Brief Guide This document has been prepared as part of the Royal Australian Historical Society’s Researching Soldiers in Your Local Community project. It is intended as a brief guide to understanding the history and structure of the First Australian Imperial Force (AIF) during World War I, so you may place your local soldier’s service in a more detailed context. A glossary of military terminology and abbreviations is provided on page 25 of the downloadable research guide for this project. The First AIF The Australian Imperial Force was first raised in 1914 in response to the outbreak of global war. By the end of the conflict, it was one of only three belligerent armies that remained an all-volunteer force, alongside India and South Africa. Though known at the time as the AIF, today it is referred to as the First AIF—just like the Great War is now known as World War I. The first enlistees with the AIF made up one and a half divisions. They were sent to Egypt for training and combined with the New Zealand brigades to form the 1st and 2nd Divisions of the Australia and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC). It was these men who served on Gallipoli, between April and December 1915. The 3rd Division of the AIF was raised in February 1916 and quickly moved to Britain for training. After the evacuation of the Gallipoli peninsula, 4th and 5th Divisions were created from the existing 1st and 2nd, before being sent to France in 1916.