The Catholic Practice of Nonviolence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brock on Curran, 'Soldiers of Peace: Civil War Pacifism and the Postwar Radical Peace Movement'

H-Peace Brock on Curran, 'Soldiers of Peace: Civil War Pacifism and the Postwar Radical Peace Movement' Review published on Monday, March 1, 2004 Thomas F. Curran. Soldiers of Peace: Civil War Pacifism and the Postwar Radical Peace Movement. New York: Fordham University Press, 2003. xv + 228 pp. $45.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8232-2210-0. Reviewed by Peter Brock (Professor Emeritus of History, University of Toronto)Published on H- Peace (March, 2004) Dilemmas of a Perfectionist Dilemmas of a Perfectionist Thomas Curran's monograph originated in a Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Notre Dame but it has been much revised since. The book's clearly written and well-constructed narrative revolves around the person of an obscure package woolen commission merchant from Philadelphia named Alfred Henry Love (1830-1913), a radical pacifist activist who was also a Quaker in all but formal membership. Love is the key figure in the book, binding Curran's chapters together into a cohesive whole. And Love's papers, and particularly his unpublished "Journal," which are located at the Swarthmore College Peace Collection, form the author's most important primary source: in fact, he uses no other manuscript collections, although, as the endnotes and bibliography show, he is well read in the published primary and secondary materials, including work on the general background of both the Civil War era and nineteenth-century pacifism. Curran has indeed rescued Love himself from near oblivion; there is little else on him apart from an unpublished Ph.D. dissertation by Robert W. Doherty (University of Pennsylvania, 1962). -

Historic Peace Churches People

The Consistent Life Ethic the vulnerable to only some groups of Mennonite: From Article 22 of the and the Historic Peace Churches people. Some care for the children in the Mennonite Confession of Faith - womb, children recently born with Mennonites, the Church of the Brethren, and disabilities, and the vulnerable among the ill. “Led by the Spirit, and beginning in the the Religious Society of Friends, which Yet they are not as clear about the problems church, we witness to all people that cooperated together in the "New Call to of war or the death penalty or policies that violence is not the will of God. We witness Peacemaking" project, have centuries of could help solve the problems of poverty against all forms of violence, including war experience in the insights of pacifism. This that threaten the very groups they assert among nations, hostility among races and is the understanding that violence is not protection for. They weaken their case by classes, abuse of children and women, ethical, nor is the apathy or cowardice that their inconsistency. Others are very sensitive violence between men and women, abortion, supports violence by others. Furthermore, to the problems of war and the death penalty and capital punishment.” the appearance of violence as a quick fix to and poverty while using euphemisms to problems is deceptive. Through hardened Brethren: From Pastor Wesley Brubaker, avoid the realities of feticide and infanticide, http://www.brfwitness.org/?p=390 hearts, lost opportunities, and over- and allowing the "right to die" become the simplified thinking, violence generally leads "duty to die" in a society still infested with “We seem to realize instinctively that to more problems and often exacerbates far too many prejudices against the abortion is gruesome. -

The Pope Is Dead Long Live the Pope by DOROTHY DAY Miserere Mei, Deus, Secundum Miserecordiam Tuam

• CATHOLl.C Sub•cription1 Vol. XXV No. 4 2.5o Per Yen Price le The _Pope Is Dead Long Live The Pope By DOROTHY DAY Miserere mei, Deus, secundum miserecordiam Tuam. [Have pitJ' Last month Bob Steed talked so on me, Lord, according to Thy mercy.] , optimistically about the loft we had These words which, aware that I was unworthy and unequal of rented that our readers began to them, I pronounced at the moment in which with trepidation I ac congratulate us on finding a place. cepted election as Supreme Pontiff, I now repeat with even more But the loft is all window, east, foundation at a time in which knowledge of the deficiencies, of the west and south and there is no failures, of the sins committed during so Ion&" a pontificate and in heat, and the one large gas stove so grave an epoch has made more clear to my mind my insufficiency is totally .inadequate. One huge and unworthiness. lleindow is out in front and the I humbly ask pardon of all whom I may h"'e offended; harmed only work we were able to do was or scandalized by word or by deed. the cleaning out and painting of I pray those whose affair it is not to bother to erect any monuments the place which had been left in to my memory: sufficient it ls that my poor mortal remains should a fearful mess by the theatrical ·be laid simplJ' in a sacred place, the more obscure the better. t!Oupe and the ballet schoof which I do not need to ask for prayers for my soul. -

Just the Police Function, Then a Response to “The Gospel Or a Glock?”

Just the Police Function, Then A Response to “The Gospel or a Glock?” Gerald W. Schlabach Introduction Consider this thought experiment: Adam and Eve have not yet sinned. In fact, they will not sin for a few decades and have begun their family. It is time for supper, but little Cain and his brother Abel are distracted. They bear no ill will, but their favorite pets, the lion and lamb, are particularly cute as they frolic together this afternoon. So Adam goes to find and hurry them home. With nary an unkind word and certainly no violence, he polices their behavior and orders their community life. For like every social arrangement, even this still-altogether-faithful community requires the police function too. A pacifist who does not recognize this point is likely to misconstrue everything I have written about “just policing.”1 Having lived a vocation for mediating between polarized Christian communities since my years in war- torn Central America, I expected a measure of misunderstanding when I proposed the agenda of just policing as a way to move ecumenical dialogue forward between pacifist and just war Christians, especially Mennonites and Catholics. Whoever seeks to engage the estranged in conversation simultaneously on multiple fronts will take such a risk.2 Deeply held identities are often at stake, and as much as the mediator may do to respect community boundaries, he or she can hardly help but threaten them simply by crossing back and forth. The risk of misunderstanding comes with the liminal territory, and nothing but a doggedly hopeful patience for continued conversation will minimize it. -

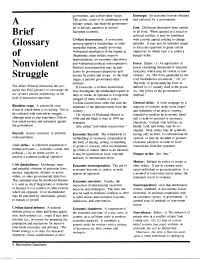

A Brief Glossary of Nonviolent Struggle

government, and subvert their troops. Embargo: An economic boycott initiated This policy, alone or in combination with and enforced by a government. A military means, has received governmen- tal or military attention in several Fast: Deliberate abstention from certain European countries. or all food. When applied in a social or Brief political conflict, it may be combined Civilian insurrection: A nonviolent with a moral appeal seeking to change Glossary uprising against a dictatorship, or other attitudes. It may also be intended simply unpopular regime, usually involving to force the opponent to grant certain widespread repudiation of the regime as objectives, in which case it is called a of illegitimate, mass strikes, massive hunger strike. demonstrations, an economic shut-down, and widespread political noncooperation. Force: Either: (1) An application of Nonviolent Political noncooperation may include power (including threatened or imposed action by government employees and sanctions, which may be violent or non- Struggle mutiny by police and troops. In the final violent). As, "the force generated by the stages, a parallel government often civil disobedience movement." Or: (2) emerges. The body or group applying force as The Albert Einstein Institution has pre- If successful, a civilian insurrection defined in (1), usually used in the plural. pared this brief glossary to encourage the may disintegrate the established regime in As, "the forces at the government's use of more precise terminology in the days or weeks, as opposed to a long-term disposal." field of nonviolent sanctions. struggle of many months or years. Civilian insurrections often end with the General strike: A work stoppage by a Bloodless coup: A successful coup departure of the deposed rulers from the majority of workers in the more impor- d'etat in which there is no killing. -

Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and McCarthy Center Student Scholarship the Common Good 2020 Changemakers: Biographies of African Americans in San Francisco Who Made a Difference David Donahue Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/mccarthy_stu Part of the History Commons CHANGEMAKERS AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE Biographies inspired by San Francisco’s Ella Hill Hutch Community Center murals researched, written, and edited by the University of San Francisco’s Martín-Baró Scholars and Esther Madríz Diversity Scholars CHANGEMAKERS: AFRICAN AMERICANS IN SAN FRANCISCO WHO MADE A DIFFERENCE © 2020 First edition, second printing University of San Francisco 2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117 Published with the generous support of the Walter and Elise Haas Fund, Engage San Francisco, The Leo T. McCarthy Center for Public Service and the Common Good, The University of San Francisco College of Arts and Sciences, University of San Francisco Student Housing and Residential Education The front cover features a 1992 portrait of Ella Hill Hutch, painted by Eugene E. White The Inspiration Murals were painted in 1999 by Josef Norris, curated by Leonard ‘Lefty’ Gordon and Wendy Nelder, and supported by the San Francisco Arts Commission and the Mayor’s Offi ce Neighborhood Beautifi cation Project Grateful acknowledgment is made to the many contributors who made this book possible. Please see the back pages for more acknowledgments. The opinions expressed herein represent the voices of students at the University of San Francisco and do not necessarily refl ect the opinions of the University or our sponsors. -

Gathered in Peace (Pax Christi USA)

Gathered In Peace (Pax Christi USA) Gathered in Peace: Forming Pax Christi Communities Gathered in Peace is a publication of Pax Christi USA and is available for download at www.paxchristiusa.org. For any other use of the publication, contact Pax Christi USA 532 W. Eighth Street Erie, PA 16502 phone: 814/453-4955 fax: 814/452-4784 e-mail: [email protected] Originally written in 1987 by Anne Shepherd, OSB, and Mary Alice Guilfuil, OSB. Revised in 1994 by Dave Robinson. With updates, 2005. © Pax Christi USA, 1987, 1994, 2005. Gathered In Peace (Pax Christi USA) Contents Introduction . p. 1 Session One: The Peace of Christ. p. 4 Session Two: Priorities and History of Pax Christi . p. 10 Session Three: Nonviolence . p. 18 Session Four: Contemporary Peacemakers . p. 26 Session Five: Where Have We Been? Where Are We Going? . p. 37 Appendix I: Pax Christi Structure . p. 43 Notes and Reflections . .p. 44 Sales Order Form . p. 46 PCUSA Membership Form . .p. 47 Gathered In Peace (Pax Christi USA) Introduction Purpose Peace I leave with you; you my own peace I give you, a peace the world cannot give. This is my gift to you. ~ John 14:27 It is this peace of Christ, a divine gift, that motivates the Catholic peace movement. The movement takes its name, Pax Christi, Peace of Christ, from this faith basis. But this peace is understood as a gift that must be shared, a blessing that requires not only a struggle against war and violence, but also the building of just structures. In pursuing this agenda Pax Christi members are encouraged by the words: “Blessed are the peacemakers, they shall be called children of God” (Matthew 5:9). -

The Cult of Liberation: the Berkeley Free Church and the Radical Church Movement 1967-1972 Volume 1

Dominican Scholar Collected Faculty and Staff Scholarship Faculty and Staff Scholarship 1977 The Cult of Liberation: The Berkeley Free Church and The Radical Church Movement 1967-1972 volume 1 Harlan Stelmach Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies, Dominican University of California, [email protected] Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Stelmach, Harlan, "The Cult of Liberation: The Berkeley Free Church and The Radical Church Movement 1967-1972 volume 1" (1977). Collected Faculty and Staff Scholarship. 52. https://scholar.dominican.edu/all-faculty/52 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Staff Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Collected Faculty and Staff Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1977 HARLAN DOUGLAS ANTHONY STELMACH ALL RIGHTS RESERVED : TlIE CULT OF LIIiER.'i.TION THE SEPKELEY FREE CHURCH and THE RADICAL CHURCH MOVEMENT 1967-1972 A dissertiatlon by Harlan Douglas Anthony _S_tein)ach presented to Tae Faculty of the Graduate Theological Union in partial fulfillment of the requirenents for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Berkeley, California May 15, 1977 Committee Signatures: Co-Coordjnator ^ y^oV^K- t\M^ Co-Coordinator f 'il -7^ ^- With special thanks to all those who have been part of the process which helped to shape me and this dissertation: MADELYN Joy Aiiy Anne Megan Linda P. ***** Tony Fred G. John M. Edie Bill Jon Joe H. Nancy Gordon Suzanne J. Bob D. Marilena Hugh Sergio Bob C. -

Message for the Age of Human Rights —What Does the Third Millennium Require? (1)

Special Series: Message for the Age of Human Rights —What Does the Third Millennium Require? (1) Daisaku Ikeda Adolfo Pérez Esquivel Here we present another in the Dialogue Among Civilizations series, this time a dialogue between Soka Gakkai International (SGI) President Daisaku Ikeda and the Argentinean human rights activist and Nobel Peace laureate Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, who met in Tokyo in December 1995. Contemplating the global outlook for the Third Millennium, in the process covering a broad range of topics including the universal nature of human rights over and above the sovereignty of national assemblies; building solidarity among ordinary people; and the great strength and potential of the world's women, they vowed to publish a collection of their dialogues. In the years following that initial meeting they have maintained a lively correspondence, and in this issue we hear about a man of indomitable spirit who has spent many years as a champion of human rights battling authoritarian evil, and the encounters that have helped shape his life. This will be the fifth article in the Dialogue Among Civilizations series by President Ikeda, following The Beauty of a Lion’s Heart (with Dr. Axinia D. Djourova of Bulgaria), Dialogues on Eastern Wisdom (with Dr. Ji Xianlin and Professor Jiang Zhongxin of China), The Spirit of India—Buddhism and Hinduism (with Dr. Ved P. Nanda, Honorary President of the World Jurist Association), and The Humanist Princi- ple—Compassion and Tolerance (with Dr. Felix Unger, President of the European Academy of Sciences and Arts). The Dawn of a New Humanism Ikeda: I greatly respect people who stand up for the dignity of humanity and strive to reform our epoch. -

PHS News August 2015

PHS News August 2015 University of Saint Joseph, Connecticut. PHS News Perhaps surprisingly given the prominence August 2015 of religion and faith to inspire peacemakers, this is the first PHS conference with its main theme on the nexus of religion and peace. The conference theme has generated a lot of interest from historians and scholars in other disciplines, including political science and religious studies. We are expecting scholars and peacemakers from around the globe in attendance: from Australia, Russia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Germany and Costa Rica. Panel topics include the American Catholic peace movement with commentary by Jon Cornell, religion and the struggle against Boko Newsletter of the Haram, and religion and the pursuit of peace Peace History Society in global contexts and many others. www.peacehistorysociety.org Our keynote speaker, Dr. Leilah Danielson, President’s Letter Associate Professor of History at Northern Arizona University, will speak directly to the larger conference themes and will reflect By Kevin J. Callahan PHS’s interdisciplinary approach. Dr. Danielson’s book, American Gandhi: A.J. Muste and the History of Radicalism in the 20th Century (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014), examines the evolving political and religious thought of A.J. Muste, a leader of the U.S. left. For the full conference program, see pages 9-14! Make plans now to attend the conference in Connecticut in October! Greetings Peace History Society Members! We will continue our tradition of announcing the winners of the Scott Bills On behalf of the entire PHS board and Memorial Prize (for a recent book on peace executive officers, it is our honor to serve history), the Charles DeBenedetti Prize (for PHS in 2015 and 2016. -

Resisting Exclusion : Global Theological Responses to Populism

Resisting exclusion : global theological responses to populism This page was generated automatically upon download from the Globethics.net Library. More information on Globethics.net see https://www.globethics.net. Data and content policy of Globethics.net Library repository see https:// repository.globethics.net/pages/policy Item Type Book Publisher Evangelische Verlangsanstalt GmbH Rights The Lutheran World Federation Download date 06/10/2021 16:43:33 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12424/3863473 Populist political movements pose serious challenges to churches and theology in many global contexts. Such movements promote marginalization and exclusion of those who are regarded as not belonging to “the people”, LWF and thereby undermine core values – dignity, equality, freedom, justice, and participation of all citizens in decision-making processes. How can theology and the churches respond to these developments? Church leaders and teaching theologians from eighteen different countries offer analyses and examples for how churches take up the challenge to resist exclusion and to strengthen participation and people’s agency. Resisting Exclusion CONTRIBUTORS: ÁDÁM, Zoltán; ANTHONY, Jeevaraj; BATARINGAYA, Pascal; BEDFORD-STROHM, Heinrich; BEROS, Daniel Carlos; BLASI, Marcia; BOZÓKI, András; FABINY, Tamás; FORSTER, Dion; GAIKWAD, Global Theological Resisting Exclusion Roger; HALLONSTEN, Gunilla; HARASTA, Eva; HÖHNE, Florian; ISAAC, Munther; JACKELÉN, Antje; KAUNDA, Chammah J.; KAUNDA, Mutale Responses to Populism Mulenga; KIM, Sung; KOOPMANN, Nico; MCINTOSH, Esther; NAUSNER, Michael; NAVRÁTILOVÁ, Olga; PALLY, Marcia; RIBET, Elisabetta; RIMMER, Chad; SEKULIC, Branko; SINN, Simone; VON SINNER, Rudolf; STJERNA, Kirsi I.; THOMAS, Linda; WERNER, Dietrich. LWF Studies 2019/1 Studies LWF ISBN 978-3-374-06174-7 EUR 22,00 [D] Resisting Exclusion. -

„Sælir Eru Friðflytjendur“

Hugvísindasvið Guðfræði- og trúarbragðafræðideild Vor 2020 „Sælir eru friðflytjendur“ Áhrif frelsissviptingar á lífsviðhorf einstaklinga sem aðhyllast friðarstefnu Ritgerð til Mag. Theol prófs í Guðfræði Stefanía Bergsdóttir Kt: 110291-3109 Leiðbeinandi: Sólveig Anna Bóasdóttir Efnisyfirlit 1. Inngangur ...................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Friðarstefna ................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Algildar og skilyrtar friðarstefnur .............................................................................................. 5 2.2 Friðarstefna og guðfræði.......................................................................................................... 7 3. Æviágrip ...................................................................................................................................... 10 3.1 Ben Salmon ............................................................................................................................ 11 3.2 Dorothy Day........................................................................................................................... 16 3.3 Alice Paul ............................................................................................................................... 20 3.4 Martin Luther King Jr.............................................................................................................