Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RELIGIOSITY and REFORM in OBERLIN, OHIO, 1833-1859 Matthew Inh Tz Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2012 PARADISE FOUND: RELIGIOSITY AND REFORM IN OBERLIN, OHIO, 1833-1859 Matthew inH tz Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hintz, Matthew, "PARADISE FOUND: RELIGIOSITY AND REFORM IN OBERLIN, OHIO, 1833-1859" (2012). All Theses. 1338. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1338 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PARADISE FOUND: RELIGIOSITY AND REFORM IN OBERLIN, OHIO, 1833-1859 A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of the Arts History by Matthew David Hintz May 2012 Accepted by: H. Roger Grant, Committee Chair C. Alan Grubb Orville V. Burton ABSTRACT Founded as a quasi-utopian society by New England evangelists, Oberlin became the central hub of extreme social reform in Ohio’s Western Reserve. Scholars have looked at Oberlin from political and cultural perspectives, but have placed little emphasis on religion. That is to say, although religion is a major highlight of secondary scholarship, few have placed the community appropriately in the dynamic of the East and West social reform movement. Historians have often ignored, or glossed over this important element and how it represented the divergence between traditional orthodoxy in New England and Middle-Atlantic states, and the new religious hybrids found in the West. -

Charles Finney's Sanctification Model in Theological Context

CHARLES FINNEY’S SANCTIFICATION MODEL IN THEOLOGICAL CONTEXT Gerald L. Priest, Ph.D. Charles G. Finney—colorful and controversial nineteenth century “father of modern evangelism.” Most responses to Finney fall into one of two categories—the highly critical and the highly complimentary.1 Unfavorable works usually attack Finney’s unorthodox doctrine and methods; the favorable defend him as a godly soul winner who is misunderstood or unjustly vilified by those who disagree with his “successful” methods.2 My contention is that a critical evaluation of Finney’s own writings will reveal that he is in substantial disagreement with the cardinal doctrines of Christianity, and that his revivalist methodology, when examined in that context, is a defective paradigm for evangelism and revival. I would also suggest that Finney’s teachings and methods have generally been harmful to evangelical Christianity. Fundamentalism was born out of intense opposition to theological liberalism, and so it would appear a mega-contradiction to even suggest that fundamentalists could ever be “taken in” by rationalism in any form. Yet, interestingly, George Marsden has suggested that one of the formative features of early fundamentalism was Scottish Common Sense philosophy, a moralistic rationalism which contributed to the evidentialist epistemology of early fundamentalist apologetics.3 One version of Common Sense, rooted in Princeton, did play a significant role in fundamentalism, as Ernest Sandeen and later Mark Noll sought to prove.4 But Finney’s “new 1Some works sympathetic to Finney include L. G. Parkhurst, Jr., Finney’s Theology: True to Scripture, True to Reason, True to Life (Edmon, OK: Revival Resources, 1990) and his article, “Charles Grandison Finney Preached For A Verdict,” Fundamentalist Journal 3 (June 1984), pp. -

1. Will Learn How to Analyze Historical Narratives

History 308/708, RN314/614, TX849 Religious Thought in America Fall Term, 2018 MWF: 1:25-2:15 Jon H. Roberts Office Hours: Mon. 3-5, Tues. 9-10, Office: 226 Bay State Road, Room 406 and by appointment 617-353-2557 (O); 781-209-0982 (H) [email protected] Course Description: Few concepts have proved more difficult to define than religion, but most students of the subject would agree that religious traditions commonly include rituals and other practices, aesthetic and emotional experiences, and a body of ideas typically expressed as beliefs. This course focuses on those beliefs during the course of American history from the first English colonial settlement to the present and on their interaction with the broader currents of American culture. Theology is the term often used to describe the systematic expression of religious doctrine. It is clearly possible, however, to discuss religious beliefs outside the context of formal theology, and it is at least arguable that some of the most influential beliefs in American history have received their most vivid and forceful expressions beyond the purview of theological discourse. Accordingly, while much of our attention in this course will focus on the works of theologians and clergy--the religious “professionals”--we shall also deal with religious strategies that a widely disparate group of other thinkers (e.g., scientists, artists, and other influential lay people) have deployed in attempting to account for the nature of the cosmos, the structure of the social order, and the dynamics of human experience. Most of the people whom we’ll be studying were committed proponents of Christianity or Judaism, but the course lectures and readings will also occasionally move outside of those traditions to include others. -

Oberlin and the Fight to End Slavery, 1833-1863

"Be not conformed to this world": Oberlin and the Fight to End Slavery, 1833-1863 by Joseph Brent Morris This thesis/dissertation document has been electronically approved by the following individuals: Baptist,Edward Eugene (Chairperson) Bensel,Richard F (Minor Member) Parmenter,Jon W (Minor Member) “BE NOT CONFORMED TO THIS WORLD”: OBERLIN AND THE FIGHT TO END SLAVERY, 1833-1863 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Joseph Brent Morris August 2010 © 2010 Joseph Brent Morris “BE NOT CONFORMED TO THIS WORLD”: OBERLIN AND THE FIGHT TO END SLAVERY, 1833-1863 Joseph Brent Morris, Ph. D. Cornell University 2010 This dissertation examines the role of Oberlin (the northern Ohio town and its organically connected college of the same name) in the antislavery struggle. It traces the antislavery origins and development of this Western “hot-bed of abolitionism,” and establishes Oberlin—the community, faculty, students, and alumni—as comprising the core of the antislavery movement in the West and one of the most influential and successful groups of abolitionists in antebellum America. Within two years of its founding, Oberlin’s founders had created a teachers’ college and adopted nearly the entire student body of Lane Seminary, who had been dismissed for their advocacy of immediate abolition. Oberlin became the first institute of higher learning to admit men and women of all races. America's most famous revivalist (Charles Grandison Finney) was among its new faculty as were a host of outspoken proponents of immediate emancipation and social reform. -

Charles G. Finney and the Second Great Awakening Charles G

Reformation &;evival A Quarterly Journal for Church Leadership Volume 6, Number 1 • Winter 1997 Charles G. Finney and the. Second Great Awakening Whatever our experience or preference or our doctrinal BobPyke emphasis, if we dig over the ground long enough we shall find a revival somewhere to support our cause. Each week during the winter of 1834-35 a tall gaunt figure of Brian Edwards stern countenance mounted the pulpit of Chatham Street Chapel, New York, to deliver a lecture on "Revivals of Hence it is the solemn duty of each objector that he exam Religion." This young Presbyterian minister, whose steely ine his own heart, and the grounds of his indifference or blue eyes "swept his audience like searchlights," was Charles opposition to revivals. If they are the genuine work of God; Grandison Finney. The New York Evangelist printed his lec if they accord with the statements of the Bible; if they are tures as they were delivered. Shortly after the series con such results as he has a right to expect under the preach cluded they were published in April 1835 in book form .... ing of the gospel, he is bound, by all the love which he bears to his Saviour, and to the souls of men, to desire and The publication of his Lectures on Revival of Religion swept pray for their increase and extension. Finney into international prominence and extended his Henry C. Fish influence and teaching far beyond the bounds of the • English-speaking world .... His Lectures in whole and in part There is in the minds of most men a tendency to extremes; have been translated into many languages and published in and that tendency is never so likely to discover itself as in countless editions, and have become the raison d'etre of all a season of general excitement. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of trie original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Family Histories 1 I. Genealogical Records

THE OBERLIN FILE: GENEALOGICAL RECORDS/ FAMILY HISTORIES I. GENEALOGICAL RECORDS/ FAMILY HISTORIES (Materials are arranged alphabetically by family name.) Box 1 Acton Family, 2003 "Descendents of Edward Harker Acton and Yeoli Stimson Acton" (enr. 1903-05, con; 1905-06, Academy). Consists of a twelve-page typescript copy of a genealogy list, with index, of the Acton Family. Prepared by Emily Acton Phillips, 2003. [Acc. 2003/062] Adams Family, n.d. Genealogy of the Adams family, who settled in Wellington, Ohio in 1823. Includes three individuals who attended the Oberlin Collegiate Institute and Oberlin College: Helen Jennette Adams (Mrs. Simeon W. Windecker), 1859 lit.; Celestia Blinn Adams (Mrs. Arthur C. Ires), enrolled 1855-62; and Mary Ann Adams (Mrs. Charles Conkling), 1839 lit. Compiled by Arthur Stanley Ives. [Acc. 2002/146] Ainsworth Family, 1997 “Ainsworth Family: Stories of Ainsworth Families of Rock Island County, Illinois, 1848-1996.” Compiled by Robert Edwin Ainsworth. (Typescript 150 pages, indexed) Allen, Otis, 2001 Draft of "The Descendants of Otis Allen" an excerpt from "Descendants of Josiah Allen and Mary Reade," by Dan H. Allen. Also filed here is correspondence with the Archives. Baker, Mary Ellen Hull, [ca. 1918?] "For MHB: A Remembrance" by Lois Baker Muehl [typescript; 64 pp; n.d., c. 1981?], received from Phil Tear, February 1, 1983. Story of Mary Ellen Hull Baker (AB 1910), wife of Arthur F. Baker (AB 1911) and mother of Robert A. Baker (AB 1939) and of Mrs. Muehl (AB 1941). Oberlin matters are dealt with on pp. 25-28 and 30-31. For Robert's death, see pp. -

The Legacy of This Place: Oberlin Ohio

THE LEGACY OF THIS PLACE: OBERLIN, OHIO Barbara Brown Zikmund, Ph.D. [This paper was prepared for a conference celebrating the 50th anniversary of Faith and Order in the United States “On Being Christian Together,” July 19-23, 2007 in Oberlin, Ohio. It is based on my doctoral dissertation: "Asa Mahan and Oberlin Perfectionism: 1835-1850" completed in 1969 at Duke University.] Beginnings Oberlin owed its beginning to a man named John Jay Shipherd; a Congregational minister with a keen desire to evangelize the West. Shepherd was working in Elyria, Ohio when he began dreaming of a religious colony where, as he put it, “consecrated souls could withdraw to Christian living in the virgin forest.” One of his students, named Philo Penfield Stewart, encouraged him and together Stewart and Shipherd conceived of a plan for a utopian colony and school. They proposed to name the colony after “John Frederic Oberlin,” a pious European pastor who was very popular with missionary minded American Christians, because in 1830 the American Sunday School Union published The Life of John Frederic Oberlin, Pastor of Waldback. Shipherd and Stewart were dreamers. In a providential sequence of events they obtained a tract of land southwest of Elyria and began convincing families to move to Oberlin. By March 1833 a small group began to clear the woods. Oberlin’s first resident, Peter Pindar Pesse, moved his family into a new log cabin a month later. By the end of 1833 approximately a dozen families called Oberlin home. [Robert Samuel Fletcher, History of Oberlin College (Oberlin: Oberlin College, 1943) 101-06.] About the same time Shipherd contracted with some teachers and made plans for a school. -

Literature of Theology and Church History in the United States and Canada Author Index

Literature of Theology and Church History in the United States and Canada Author Index Abbot, Abiel. Abercrombie, James. A discourse delivered at Plymouth December 22, A sermon, preached in Christ church and St. 1809, at the celebration of the 188th anniversary of Peter's, Philadelphia: on Wednesday, May 9, 1798. the landing of our forefathers in that place. Philadelphia: John Ormrod, no. 41, Chestnut-street. Boston: Greenough and Stebbins. 1810 [1798] pastor of the First church in Beverly; LC# 25-3660. Being the day appointed by the President, as a day of Fiche: 40,028 fasting, humiliation, and prayer, throughout the United States of North America; LC# 20-12779. Abbot, Abiel. Fiche: 40,027 Reply to Mr. Abbot's statement of proceedings in the First Society in Coventry, Conn. An Account of the reasons why a considerable Hartford: B. Gleason. 1812 number... belonging to the New North congregation Church History in Boston, could not consent to Mr. Peter Thacher's by the Association in Tolland County. ordination there. Fiche: 4,871 [Boston: s.n.]. 1720 Dogmatic Theology Abbot, Abiel. Fiche: 4,962 A statement of proceedings in the First Society in Coventry, Conn.: which terminated in the removal of Ackerman, A. W. the pastor. The price of peace. A story of the times of Ahab, Boston: J. Eliot. 1811 king of Israel. Practical Theology Chicago, A. C. McClurg and company. 1894 Fiche: 4,848 LC# 5-42990. Fiche: A-37,222 Abbott, John Stevens Cabot. History of King Philip, sovereign chief of the Adams, Amos. Wampanoags. Religious liberty an invaluable blessing. -

Oberlin Perfectionism and Its Edwardsean Origins Allen C

Civil War Era Studies Faculty Publications Civil War Era Studies 1996 Oberlin Perfectionism and Its Edwardsean Origins Allen C. Guelzo Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cwfac Part of the Christianity Commons, History of Christianity Commons, History of Religion Commons, Intellectual History Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Guelzo, Allen C. "Oberlin Perfectionism and Its Edwardsean Origins." Jonathan Edwards’s Writings: Text, Context, Interpretation ed. Stephen J. Stein (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1996), 159-174. This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cwfac/43 This open access book chapter is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Oberlin Perfectionism and Its Edwardsean Origins Abstract An impression has very generally prevailed," wrote James Harris Fairchild toward the end of his twenty-three- year presidency of Oberlin College, "that the theological views unleashed at Oberlin College by the late Rev. Charles Grandison Finney & his Associates involves a considerable departure from the accepted orthodox faith." It was an impression that Fairchild believed to be inaccurate, and he would probably be horrified to discover a century later that the prevailing impression the "Oberlin Theology" has made on historians of the nineteenth-century United States continues to be one in which Oberlin stands for almost all the progressive and enthusiastic unorthodoxies of the Age of Jackson, from Sylvester Graham's crackers to moral perfectionism. -

The Ohio Archivist Fall 1987 SOA Fall Meeting Is Scheduled for Sept

The Society d O,io tivists The Ohio Archivist Fall 1987 SOA fall meeting is scheduled for Sept. 24-25 in Bowling Green, Ohio Jerome Library, Bowling Green State University PHOTO courtesy of Bowling Green State University Dr. Raymond K. Tucker, nationally known for his semi- The meeting's opening session, from 1-2:45 p.m. Thurs- nars in interpersonal communication, will be the featured day, will address current technological trends in records speaker when the Society of Ohio Archivists holds its fall management and will be led by Richard Sayre, Assistant meeting in Bowling Green September 24 and 25. The meet- Administrator for Information Management at the State ing will be held at the Bowling Green Holiday Inn with Records Center in Columbus. Last spring's issue of The Ohio registration set for noon to 1 p.m ..on Thursday, September Archivist featured an article on the innovative techniques 24. A program brochure has also been prepared. being used at the State Records Center; Mr. Sayre will amplify the information given in that piece and bring us up Following Dr. Tucker's address, the meeting will break for to date with the progress being made at the Center. Mr. dinner. Later, from 8-10 p.m., the Center for Archival Sayre will be joined at this session by Ann Gilliand of the Collections at Bowling Green State University will host a University of Cincinnati's Archives and Rare Book Depart- reception at Jerome Library, as well as provide tours of the ment. Given her focus from the point of view of an academic CAC and Popular Culture and Music libraries. -

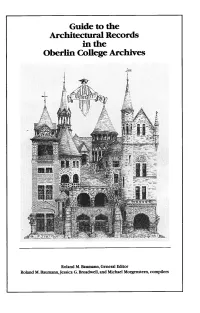

Guide to the Architectural Records in the Oberlin College Archives

Guide to the Architectural Records in the Oberlin College Archives Roland M. Baumann, General Editor Roland M. Baumann, Jessica G. Broadwell, and Michael Morgenstem, compilers ON THE COVER: The cover drawing depicts the Oberlin Stone Age, which lasted for a q>iarter-century after 1885. Included in the montage is the tower of the College Chapel, tower of Coimcil Hall, tower of Talcott Hall, entry of Spear Library Oater, Spear Laboratory), tower and entry of Baldwin Cottage, tower of Warner Hall, and tower and entry of Peters Hall. Artist is Herbert Fairchild Steven, an 1890s student who studied art. Drawing appears in the 1897 Hi-O-Hi, page 13. Unless otherwise noted,.aU photographs are from the holdings of the Oberlin College Archives. Guide to the Architectural Records in the Oberlin College Archives Guide to the Architectural Records in the Oherlin College Arcliives Roland M. Baumann, General Editor Roland M. Baumann, Jessica G. Broadwell, and Michael Morgenstem, compilers Gertrude F.Jacob Archival Publications Fimd Oberlin College Oberlin, Ohio 1996 Copyright ©1996 Oberlin College Printed on recycled and acid-free paper s Dedicated to William E. Bigglestone Oberlin College Archivist, 1966-1986 Oberlin College Campus ^ S^ 1989 Alphabetical Usting s/Camegie Building 52 KettoiiKHaU 49 AUm Memorial Alt Museum 56 King Bimding 22 AUencraft (Russian House) S LM3 (Afrikan Heritage House) 9 Afboretum 1 Malkny House _ 59 Asia House (Quadrant^e) 53 Memorial Arch 23 Athletic Relds 36 SedeyG.MuddCaitCT 30 Bailey House (Frendi House) 44 Noah HaU