The Lightning Whelk: an Enduring Icon of Southeastern North American Spirituality ⇑ William H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population and Reproductive Biology of the Channeled Whelk, Busycotypus Canaliculatus, in the US Mid-Atlantic

W&M ScholarWorks VIMS Articles 2017 Population and Reproductive Biology of the Channeled Whelk, Busycotypus canaliculatus, in the US Mid-Atlantic Robert A. Fisher Virginia Institute of Marine Science, [email protected] David Rudders Virginia Institute of Marine Science, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles Part of the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Robert A. and Rudders, David, "Population and Reproductive Biology of the Channeled Whelk, Busycotypus canaliculatus, in the US Mid-Atlantic" (2017). VIMS Articles. 304. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles/304 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in VIMS Articles by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Shellfish Research, Vol. 36, No. 2, 427–444, 2017. POPULATION AND REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY OF THE CHANNELED WHELK, BUSYCOTYPUS CANALICULATUS, IN THE US MID-ATLANTIC ROBERT A. FISHER* AND DAVID B. RUDDERS Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary, PO Box 1346, Gloucester Point, VA 23062 ABSTRACT Channeled whelks, Busycotypus canaliculatus, support commercial fisheries throughout their range along the US Atlantic seaboard. Given the modest amounts of published information available on channeled whelk, this study focuses on understanding the temporal and spatial variations in growth and reproductive biology in the Mid-Atlantic region. Channeled whelks were sampled from three inshore commercially harvested resource areas in the US Mid-Atlantic: Ocean City, MD (OC); Eastern Shore of Virginia (ES); and Virginia Beach, VA (VB). The largest whelk measured 230-mm shell length (SL) and was recorded from OC. -

Age, Growth, Size at Sexual Maturity and Reproductive Biology of Channeled Whelk, Busycotypus Canaliculatus, in the U.S. Mid-Atlantic

Age, Growth, Size at Sexual Maturity and Reproductive Biology of Channeled Whelk, Busycotypus canaliculatus, in the U.S. Mid-Atlantic October 2015 Robert A. Fisher Virginia Institute of Marine Science Virginia Sea Grant-Affiliated Extension (In cooperation with Bernie’s Conchs) Robert A. Fisher Marine Advisory Services Virginia Institute of Marine Science P.O. Box 1346 Gloucester Point, VA 23062 804/684-7168 [email protected] www.vims.edu/adv VIMS Marine Resource Report No. 2015-15 VSG-15-09 Additional copies of this publication are available from: Virginia Sea Grant Communications Virginia Institute of Marine Science P.O. Box 1346 Gloucester Point, VA 23062 804/684-7167 [email protected] Cover Photo: Robert Fisher, VIMS MAS This work is affiliated with the Virginia Sea Grant Program, by NOAA Office of Sea Grant, U.S. Depart- ment of Commerce, under Grant No. NA10OAR4170085. The views expressed herein do not necessar- ily reflect the views of any of those organizations. Age, Growth, Size at Sexual Maturity and Reproductive Biology of Channeled Whelk, Busycotypus canaliculatus, in the U.S. Mid-Atlantic Final Report for the Virginia Fishery Resource Grant Program Project 2009-12 Abstract The channeled whelk, Busycotypus canaliculatus, was habitats, though mixing is observed inshore along shallow sampled from three in-shore commercially harvested waters of continental shelf. Channeled whelks are the resource areas in the US Mid-Atlantic: off Ocean City, focus of commercial fisheries throughout their range (Davis Maryland (OC); Eastern Shore of Virginia (ES); and and Sisson 1988, DiCosimo 1988, Bruce 2006, Fisher and Virginia Beach, Virginia (VB). -

Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus Dofleini) Care Manual

Giant Pacific Octopus Insert Photo within this space (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual CREATED BY AZA Aquatic Invertebrate Taxonomic Advisory Group IN ASSOCIATION WITH AZA Animal Welfare Committee Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Aquatic Invertebrate Taxon Advisory Group (AITAG) (2014). Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) Care Manual. Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Silver Spring, MD. Original Completion Date: September 2014 Dedication: This work is dedicated to the memory of Roland C. Anderson, who passed away suddenly before its completion. No one person is more responsible for advancing and elevating the state of husbandry of this species, and we hope his lifelong body of work will inspire the next generation of aquarists towards the same ideals. Authors and Significant Contributors: Barrett L. Christie, The Dallas Zoo and Children’s Aquarium at Fair Park, AITAG Steering Committee Alan Peters, Smithsonian Institution, National Zoological Park, AITAG Steering Committee Gregory J. Barord, City University of New York, AITAG Advisor Mark J. Rehling, Cleveland Metroparks Zoo Roland C. Anderson, PhD Reviewers: Mike Brittsan, Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Paula Carlson, Dallas World Aquarium Marie Collins, Sea Life Aquarium Carlsbad David DeNardo, New York Aquarium Joshua Frey Sr., Downtown Aquarium Houston Jay Hemdal, Toledo -

This Is Not a Citeable Document

This Meeting was Cancelled. THIS IS NOT A CITEABLE DOCUMENT NATIONAL SHELLFISHERIES ASSOCIATION Program and Abstracts of the 112th Annual Meeting March 29 – April 2, 2020 Baltimore, Maryland NSA 112th ANNUAL MEETING 1DWLRQDO6KHOO¿VKHULHV$VVRFLDWLRQ 7KH&URZQH3OD]D%DOWLPRUH,QQHU+DUERU+RWHO%$/7,025(0$5</$1' 0DUFK±$SULO 681'$<0$5&+ 6:30 PM 678'(1725,(17$7,21 DO NOT &DUUROO CITE 7:00 PM 35(6,'(17¶65(&(37,21 ,QWHUQDWLRQDO$%& 021'$<0$5&+ 678'(17%5($.)$67 VWXGHQWVRQO\ 6:30-8:00 AM +DOORI)DPH 3/(1$5</(&785(5RJHU0DQQ(9LUJLQLD,QVWLWXWHRI0DULQH6FLHQFH 8:00-8:50 AM ,QWHUQDWLRQDO$%& ,QWHUQDWLRQDO$ ,QWHUQDWLRQDO% ,QWHUQDWLRQDO& &DUUROO 21(+($/7+(3,*(120(6 6+(//),6+ 6+(//),6+*(1(7,&6 9:00-10:30 AM $1'0,&52%,20(6)520 5(6725$7,21$1' MUSSELS $1'*(120,&6 62,/723(23/(:25.6+23 &216(59$7,21 10:30-11:00AM 0251,1*%5($. 21(+($/7+(3,*(120(6 6+(//),6+ 6+(//),6+*(1(7,&6 6+(//),6+$48$&8/785( 11:00-12:30PM $1'0,&52%,20(6)520 5(6725$7,21$1' $1'*(120,&6 %86,1(66$1'(&2120,&6 62,/723(23/(:25.6+23 &216(59$7,21 12:30-1:30 PM /81&+%5($. 21(+($/7+(3,*(120(6 6+(//),6+ 6+(//),6+*(1(7,&6 1:30-2:15 PM $1'0,&52%,20(6)520 5(6725$7,21$1' /($6,1*$1'3(50,77,1* $1'*(120,&6 62,/723(23/(:25.6+23 &216(59$7,21 21(+($/7+(3,*(120(6 6+(//),6+ 6+(//),6+*(1(7,&6 2:15-3:00 PM $1'0,&52%,20(6)520 5(6725$7,21$1' /($6,1*$1'3(50,77,1* $1'*(120,&6 62,/723(23/(:25.6+23 &216(59$7,21 3:00-3:30 PM $)7(51221%5($. -

The Mussel Resources of the North Atlantic Region

United states Depa tment of the Interior, Oscar ~ . Chapman, Secretary Fish and ice, Albert M. Day, Director J Fishery Leaflet 364 Wash in ton 25 D. C. Januar 1950 THE MUSSEL RESOURCES OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC REGION ~RT J --THE SURVEY TO DISCOVER THE LOCATIONS AND AREAS OF THE NORTH ATLANTIC MUSSEL-PRODUCING BEDS By Leslie W. Scattergood~~ and Clyde C, Taylor ~d~ '!his is the first of three papers discussing the World War II pro motion of the North Atlantic mussel fishery. The present article is primarily concerned "'i th the quantitative resul ts of a survey of the productivi~ of mussel areas. INTRODUCTION During the recent war, the fishing industry had tte problem of increasing its production despite relative shortages of manpower, equipment, and materials o One of the ways of efficiently augmenting the catch of fish and shellfish was to uti lize species ordinarily disregarded. One of the probable sources of sea food was the edible mussel (yGtilus edulis), which is so common along , the North Atlantic Coast of the United States. This species cap be harvested dur ing that time of the year when the small-boat fishery is least active. In the late winter and the spring months, the mussels a,re in good con dition for marketing, as it is then that they reach their fattest condition, and in this period other fishing activities are at a low level. The mussel, although relatively unknown to the American public p has attained great popularity in Europe. Large quantities have been consumed in European coun tries for hundreds of yearso The annual English, Welsh, and Scotch production of this shellfish, as re corded in the statistical reports of the British Ministry of Agriculture and Fish eries" ave,raged about 19 million pounds ("in the shell" weight) for the lS-year period between 1924 and 1938. -

Shelled Molluscs

Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS) Archimer http://www.ifremer.fr/docelec/ ©UNESCO-EOLSS Archive Institutionnelle de l’Ifremer Shelled Molluscs Berthou P.1, Poutiers J.M.2, Goulletquer P.1, Dao J.C.1 1 : Institut Français de Recherche pour l'Exploitation de la Mer, Plouzané, France 2 : Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France Abstract: Shelled molluscs are comprised of bivalves and gastropods. They are settled mainly on the continental shelf as benthic and sedentary animals due to their heavy protective shell. They can stand a wide range of environmental conditions. They are found in the whole trophic chain and are particle feeders, herbivorous, carnivorous, and predators. Exploited mollusc species are numerous. The main groups of gastropods are the whelks, conchs, abalones, tops, and turbans; and those of bivalve species are oysters, mussels, scallops, and clams. They are mainly used for food, but also for ornamental purposes, in shellcraft industries and jewelery. Consumed species are produced by fisheries and aquaculture, the latter representing 75% of the total 11.4 millions metric tons landed worldwide in 1996. Aquaculture, which mainly concerns bivalves (oysters, scallops, and mussels) relies on the simple techniques of producing juveniles, natural spat collection, and hatchery, and the fact that many species are planktivores. Keywords: bivalves, gastropods, fisheries, aquaculture, biology, fishing gears, management To cite this chapter Berthou P., Poutiers J.M., Goulletquer P., Dao J.C., SHELLED MOLLUSCS, in FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE, from Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS), Developed under the Auspices of the UNESCO, Eolss Publishers, Oxford ,UK, [http://www.eolss.net] 1 1. -

Lab 5: Phylum Mollusca

Biology 18 Spring, 2008 Lab 5: Phylum Mollusca Objectives: Understand the taxonomic relationships and major features of mollusks Learn the external and internal anatomy of the clam and squid Understand the major advantages and limitations of the exoskeletons of mollusks in relation to the hydrostatic skeletons of worms and the endoskeletons of vertebrates, which you will examine later in the semester Textbook Reading: pp. 700-702, 1016, 1020 & 1021 (Figure 47.22), 943-944, 978-979, 1046 Introduction The phylum Mollusca consists of over 100,000 marine, freshwater, and terrestrial species. Most are familiar to you as food sources: oysters, clams, scallops, and yes, snails, squid and octopods. Some also serve as intermediate hosts for parasitic trematodes, and others (e.g., snails) can be major agricultural pests. Mollusks have many features in common with annelids and arthropods, such as bilateral symmetry, triploblasty, ventral nerve cords, and a coelom. Unlike annelids, mollusks (with one major exception) do not possess a closed circulatory system, but rather have an open circulatory system consisting of a heart and a few vessels that pump blood into coelomic cavities and sinuses (collectively termed the hemocoel). Other distinguishing features of mollusks are: z A large, muscular foot variously modified for locomotion, digging, attachment, and prey capture. z A mantle, a highly modified epidermis that covers and protects the soft body. In most species, the mantle also secretes a shell of calcium carbonate. z A visceral mass housing the internal organs. z A mantle cavity, the space between the mantle and viscera. Gills, when present, are suspended within this cavity. -

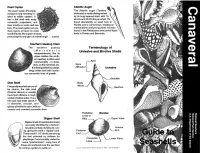

Terminology of Univalve and Bivalve Shells 2.1.3

Pearl Oyster Atlantic Auger • The pearl oyster (Pinctada The Atlantic auger (Terebra radiata) is only remotely re dislocata) is easily distinguished lated to edible oysters. It by its long tapered shell, with 15 y o has a flat shell with scaly whorls and 20-25 ribs per whorl. It's * concentric projections, and found abundantly on sand bars in V lives mostly on rocks and sea Florida and is carnivorous, feeding on fans. The pearl oyster can pro marine worms and young clams. It is also ^._ found in the Pleistocene time period fossil <• 3 duce layers of nacre to cover small irritants, like a grain of sand, beds in Florida and Bermuda. producing the only gem of animal origin ... a pearl. Southern Quahog Clam < The southern quahog Terminology of (Mercenaria Univalve and Bivalve Shells <D campechiensis), like its close relative the north ern quahog, is often used commercially - in chow ders, on the half shell, etc. 3 It is distinguished by a large, dingy white shell with numer ous concentric lines of growth. Disk Shell Frequently washed ashore af ter storms, the disk shell (Dosinia discus) is usually found just offshore in mod erately shallow water. It is a trim and neat shell, about 3" in diameter, circular, and glossy off-white in color, with nu merous and crowded concentric lines. c z z in B » Slipper Shell V/ r+ ,-* nô'ô Slipper shells (Crepidulafornicata) S? 3 3 are easily identified by a horizon -n — — tal plate partially dividing its cav S> TJ V> 3 Q> ffl ity, giving the shell a "slipper" look. -

ASFIS ISSCAAP Fish List February 2007 Sorted on Scientific Name

ASFIS ISSCAAP Fish List Sorted on Scientific Name February 2007 Scientific name English Name French name Spanish Name Code Abalistes stellaris (Bloch & Schneider 1801) Starry triggerfish AJS Abbottina rivularis (Basilewsky 1855) Chinese false gudgeon ABB Ablabys binotatus (Peters 1855) Redskinfish ABW Ablennes hians (Valenciennes 1846) Flat needlefish Orphie plate Agujón sable BAF Aborichthys elongatus Hora 1921 ABE Abralia andamanika Goodrich 1898 BLK Abralia veranyi (Rüppell 1844) Verany's enope squid Encornet de Verany Enoploluria de Verany BLJ Abraliopsis pfefferi (Verany 1837) Pfeffer's enope squid Encornet de Pfeffer Enoploluria de Pfeffer BJF Abramis brama (Linnaeus 1758) Freshwater bream Brème d'eau douce Brema común FBM Abramis spp Freshwater breams nei Brèmes d'eau douce nca Bremas nep FBR Abramites eques (Steindachner 1878) ABQ Abudefduf luridus (Cuvier 1830) Canary damsel AUU Abudefduf saxatilis (Linnaeus 1758) Sergeant-major ABU Abyssobrotula galatheae Nielsen 1977 OAG Abyssocottus elochini Taliev 1955 AEZ Abythites lepidogenys (Smith & Radcliffe 1913) AHD Acanella spp Branched bamboo coral KQL Acanthacaris caeca (A. Milne Edwards 1881) Atlantic deep-sea lobster Langoustine arganelle Cigala de fondo NTK Acanthacaris tenuimana Bate 1888 Prickly deep-sea lobster Langoustine spinuleuse Cigala raspa NHI Acanthalburnus microlepis (De Filippi 1861) Blackbrow bleak AHL Acanthaphritis barbata (Okamura & Kishida 1963) NHT Acantharchus pomotis (Baird 1855) Mud sunfish AKP Acanthaxius caespitosa (Squires 1979) Deepwater mud lobster Langouste -

Behavior and Movement of Whelks

MOVEMENT AND BEHAVIOR OF WHELKS (FAMILY MELONGENIDAE) IN GEORGIA COASTAL WATERS by JACOB D. SHALACK (Under the Direction of Randal L. Walker) ABSTRACT Two studies were performed: 1) to examine whelk harvest potential and the pot efficiency of five types of traps and 2) to examine the movement and behavior of the knobbed whelk, Busycon carica (Gmelin 1791) on intertidal flats. A total of 734 whelks [47.7% Busycotypus canalicalatus (Linnaeus, 1758), 34.7% B. carica, 17.6% Busycotypus spiratus (Hollister 1958)] were caught during the trapping study in Wassaw Sound and Beard Creek, Georgia. Traps with smooth plastic surfaces caught more whelks than traps without at both locations. During the tracking study at Wassaw Island, Georgia, initial whelk movement was a random spreading out from the release point. By day 8, whelks had concentrated on and near live oyster reefs. The average individual minimum daily movement rate was significantly shorter for males as compared to females (ANOVA p<0.0001). Whelks also shifted from surface to more buried positions as daytime temperatures increased (Chi squared α=0.05). INDEX WORDS: Whelk, Movement, Trapping, Fishery, Wassaw Sound, GIS, Busycon, Busycotypus MOVEMENT AND BEHAVIOR OF WHELKS (FAMILY MELONGENIDAE) IN GEORGIA COASTAL WATERS by JACOB D. SHALACK A.S., Darton College, 1999 A.B., University of Georgia, 2001 B.S., University of Georgia, 2004 A Thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2007 © 2007 Jacob D. Shalack All Rights Reserved MOVEMENT AND BEHAVIOR OF WHELKS (FAMILY MELONGENIDAE) IN GEORGIA COASTAL WATERS by JACOB D. -

Click Here to Download

Interested in European research? RTD info is our quarterly magazine keeping you in touch with main developments (results, programmes, events, etc.). It is available in English, French and German. A free sample copy or free subscription can be obtained from: Directorate-General for Research Communication Unit European Commission Rue de la Loi/Wetstraat 200 B-1049 Brussels Fax (32-2) 29-58220 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http:/europa.eu.int/comm/research/rtdinfo.html EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate-General for Research Unit AP.2 - COST Contact: Mrs Marija Skerlj Address: European Commission, rue de la Loi/Wetstraat 200 (SDME 1/43), B-1049 Brussels - Tel. (32-2) 29-91599; fax (32-2) 29-65987 European Commission COST Action 99 Research action on food consumption and composition data LanguaL 2000 The LanguaL thesaurus Working Group on food description, terminology and nomenclature Edited by: Anders Møller and Jayne Ireland Directorate-General for Research 2000 EUR 19540 LEGAL NOTICE Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of the following information. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu.int). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2000 ISBN 92-828-9758-3 © European Communities, 2000 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Belgium PRINTED ON WHITE CHLORINE-FREE PAPER LanguaL 2000 THE LANGUAL THESAURUS PREPARED BY ANDERS MØLLER JAYNE IRELAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to express our gratitude to the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN) of the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for so willingly sharing all the information concerning LanguaL and other indexing systems at the FDA. -

Age-Dependent Zonation of the Periwinkle Littorina Littorea (L.) in the Wadden Sea

Helgol Mar Res (2000) 54:224–229 DOI 10.1007/s101520000054 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Bettina Saier Age-dependent zonation of the periwinkle Littorina littorea (L.) in the Wadden Sea Received: 24 May 2000 / Received in revised form: 25 September 2000 / Accepted: 26 September 2000 / Published online: 16 November 2000 © Springer-Verlag and AWI 2000 Abstract On sedimentary tidal flats near the island of variations in mean size of intertidal snails with shore lev- Sylt (German Bight, North Sea) abundance and size dis- el have also been widely reported (e.g. Williams 1964; tribution of periwinkles, Littorina littorea L., were stud- Edwards 1969; Vermeij 1972; Underwood 1973, 1979; ied in low intertidal and in shallow and deep subtidal Chapman 1994; Williams 1995). Among Littorinidae, mussel beds (Mytilus edulis L.). In low intertidal mussel the largest individuals often occur towards the species’ beds, surveys revealed that high densities (1,369±571 m–2) upper distributional limits and the smallest towards the of juvenile snails (≤13 mm) were positively correlated lower distributional limits, but there are many exceptions with strong barnacle epigrowth (Semibalanus balanoides to this (Vermeij 1972). The periwinkle Littorina littorea L. and Balanus crenatus Bruguière) on mussels. A sub- (L.), in particular, exhibits highly variable patterns with sequent field experiment showed that recruitment of L. complex size gradients (Smith and Newell 1955; littorea was restricted to the intertidal zone. Abundances Williams 1964; Vermeij 1972). Furthermore L. littorea is of periwinkles (213±114 m–2) and barnacles abruptly de- the only littorinid species which is commonly found on creased in the adjacent shallow subtidal zone, which both hard substrates and in soft bottom environments served as a habitat for older snails (>13 mm).