Introduction to Computer Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

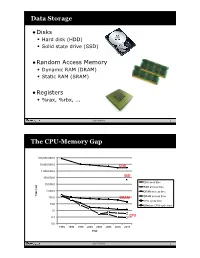

Data Storage the CPU-Memory

Data Storage •Disks • Hard disk (HDD) • Solid state drive (SSD) •Random Access Memory • Dynamic RAM (DRAM) • Static RAM (SRAM) •Registers • %rax, %rbx, ... Sean Barker 1 The CPU-Memory Gap 100,000,000.0 10,000,000.0 Disk 1,000,000.0 100,000.0 SSD Disk seek time 10,000.0 SSD access time 1,000.0 DRAM access time Time (ns) Time 100.0 DRAM SRAM access time CPU cycle time 10.0 Effective CPU cycle time 1.0 0.1 CPU 0.0 1985 1990 1995 2000 2003 2005 2010 2015 Year Sean Barker 2 Caching Smaller, faster, more expensive Cache 8 4 9 10 14 3 memory caches a subset of the blocks Data is copied in block-sized 10 4 transfer units Larger, slower, cheaper memory Memory 0 1 2 3 viewed as par@@oned into “blocks” 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Sean Barker 3 Cache Hit Request: 14 Cache 8 9 14 3 Memory 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Sean Barker 4 Cache Miss Request: 12 Cache 8 12 9 14 3 12 Request: 12 Memory 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Sean Barker 5 Locality ¢ Temporal locality: ¢ Spa0al locality: Sean Barker 6 Locality Example (1) sum = 0; for (i = 0; i < n; i++) sum += a[i]; return sum; Sean Barker 7 Locality Example (2) int sum_array_rows(int a[M][N]) { int i, j, sum = 0; for (i = 0; i < M; i++) for (j = 0; j < N; j++) sum += a[i][j]; return sum; } Sean Barker 8 Locality Example (3) int sum_array_cols(int a[M][N]) { int i, j, sum = 0; for (j = 0; j < N; j++) for (i = 0; i < M; i++) sum += a[i][j]; return sum; } Sean Barker 9 The Memory Hierarchy The Memory Hierarchy Smaller On 1 cycle to access CPU Chip Registers Faster Storage Costlier instrs can L1, L2 per byte directly Cache(s) ~10’s of cycles to access access (SRAM) Main memory ~100 cycles to access (DRAM) Larger Slower Flash SSD / Local network ~100 M cycles to access Cheaper Local secondary storage (disk) per byte slower Remote secondary storage than local (tapes, Web servers / Internet) disk to access Sean Barker 10. -

Caching Basics

Introduction Why memory subsystem design is important • CPU speeds increase 25%-30% per year • DRAM speeds increase 2%-11% per year Autumn 2006 CSE P548 - Memory Hierarchy 1 Memory Hierarchy Levels of memory with different sizes & speeds • close to the CPU: small, fast access • close to memory: large, slow access Memory hierarchies improve performance • caches: demand-driven storage • principal of locality of reference temporal: a referenced word will be referenced again soon spatial: words near a reference word will be referenced soon • speed/size trade-off in technology ⇒ fast access for most references First Cache: IBM 360/85 in the late ‘60s Autumn 2006 CSE P548 - Memory Hierarchy 2 1 Cache Organization Block: • # bytes associated with 1 tag • usually the # bytes transferred on a memory request Set: the blocks that can be accessed with the same index bits Associativity: the number of blocks in a set • direct mapped • set associative • fully associative Size: # bytes of data How do you calculate this? Autumn 2006 CSE P548 - Memory Hierarchy 3 Logical Diagram of a Cache Autumn 2006 CSE P548 - Memory Hierarchy 4 2 Logical Diagram of a Set-associative Cache Autumn 2006 CSE P548 - Memory Hierarchy 5 Accessing a Cache General formulas • number of index bits = log2(cache size / block size) (for a direct mapped cache) • number of index bits = log2(cache size /( block size * associativity)) (for a set-associative cache) Autumn 2006 CSE P548 - Memory Hierarchy 6 3 Design Tradeoffs Cache size the bigger the cache, + the higher the hit ratio -

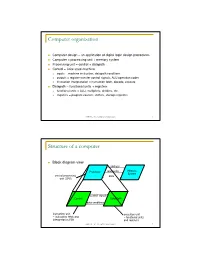

Computer Organization

Computer organization Computer design – an application of digital logic design procedures Computer = processing unit + memory system Processing unit = control + datapath Control = finite state machine inputs = machine instruction, datapath conditions outputs = register transfer control signals, ALU operation codes instruction interpretation = instruction fetch, decode, execute Datapath = functional units + registers functional units = ALU, multipliers, dividers, etc. registers = program counter, shifters, storage registers CSE370 - XI - Computer Organization 1 Structure of a computer Block diagram view address Processor read/write Memory System central processing data unit (CPU) control signals Control Data Path data conditions instruction unit execution unit œ instruction fetch and œ functional units interpretation FSM and registers CSE370 - XI - Computer Organization 2 Registers Selectively loaded – EN or LD input Output enable – OE input Multiple registers – group 4 or 8 in parallel LD OE D7 Q7 OE asserted causes FF state to be D6 Q6 connected to output pins; otherwise they D5 Q5 are left unconnected (high impedance) D4 Q4 D3 Q3 D2 Q2 LD asserted during a lo-to-hi clock D1 Q1 transition loads new data into FFs D0 CLK Q0 CSE370 - XI - Computer Organization 3 Register transfer Point-to-point connection MUX MUX MUX MUX dedicated wires muxes on inputs of each register rs rt rd R4 Common input from multiplexer load enables rs rt rd R4 for each register control signals MUX for multiplexer Common bus with output enables output enables and load rs rt rd R4 enables for each register BUS CSE370 - XI - Computer Organization 4 Register files Collections of registers in one package two-dimensional array of FFs address used as index to a particular word can have separate read and write addresses so can do both at same time 4 by 4 register file 16 D-FFs organized as four words of four bits each write-enable (load) 3E RB read-enable (output enable) RA WE (- WB (. -

Chapter 5 Multiprocessors and Thread-Level Parallelism

Computer Architecture A Quantitative Approach, Fifth Edition Chapter 5 Multiprocessors and Thread-Level Parallelism Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Centralized SMA – shared memory architecture 3. Performance of SMA 4. DMA – distributed memory architecture 5. Synchronization 6. Models of Consistency Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 2 1. Introduction. Why multiprocessors? Need for more computing power Data intensive applications Utility computing requires powerful processors Several ways to increase processor performance Increased clock rate limited ability Architectural ILP, CPI – increasingly more difficult Multi-processor, multi-core systems more feasible based on current technologies Advantages of multiprocessors and multi-core Replication rather than unique design. Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 3 Introduction Multiprocessor types Symmetric multiprocessors (SMP) Share single memory with uniform memory access/latency (UMA) Small number of cores Distributed shared memory (DSM) Memory distributed among processors. Non-uniform memory access/latency (NUMA) Processors connected via direct (switched) and non-direct (multi- hop) interconnection networks Copyright © 2012, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 4 Important ideas Technology drives the solutions. Multi-cores have altered the game!! Thread-level parallelism (TLP) vs ILP. Computing and communication deeply intertwined. Write serialization exploits broadcast communication -

45-Year CPU Evolution: One Law and Two Equations

45-year CPU evolution: one law and two equations Daniel Etiemble LRI-CNRS University Paris Sud Orsay, France [email protected] Abstract— Moore’s law and two equations allow to explain the a) IC is the instruction count. main trends of CPU evolution since MOS technologies have been b) CPI is the clock cycles per instruction and IPC = 1/CPI is the used to implement microprocessors. Instruction count per clock cycle. c) Tc is the clock cycle time and F=1/Tc is the clock frequency. Keywords—Moore’s law, execution time, CM0S power dissipation. The Power dissipation of CMOS circuits is the second I. INTRODUCTION equation (2). CMOS power dissipation is decomposed into static and dynamic powers. For dynamic power, Vdd is the power A new era started when MOS technologies were used to supply, F is the clock frequency, ΣCi is the sum of gate and build microprocessors. After pMOS (Intel 4004 in 1971) and interconnection capacitances and α is the average percentage of nMOS (Intel 8080 in 1974), CMOS became quickly the leading switching capacitances: α is the activity factor of the overall technology, used by Intel since 1985 with 80386 CPU. circuit MOS technologies obey an empirical law, stated in 1965 and 2 Pd = Pdstatic + α x ΣCi x Vdd x F (2) known as Moore’s law: the number of transistors integrated on a chip doubles every N months. Fig. 1 presents the evolution for II. CONSEQUENCES OF MOORE LAW DRAM memories, processors (MPU) and three types of read- only memories [1]. The growth rate decreases with years, from A. -

Review of Computer Architecture

Basic Computer Architecture CSCE 496/896: Embedded Systems Witawas Srisa-an Review of Computer Architecture Credit: Most of the slides are made by Prof. Wayne Wolf who is the author of the textbook. I made some modifications to the note for clarity. Assume some background information from CSCE 430 or equivalent von Neumann architecture Memory holds data and instructions. Central processing unit (CPU) fetches instructions from memory. Separate CPU and memory distinguishes programmable computer. CPU registers help out: program counter (PC), instruction register (IR), general- purpose registers, etc. von Neumann Architecture Memory Unit Input CPU Output Unit Control + ALU Unit CPU + memory address 200PC memory data CPU 200 ADD r5,r1,r3 ADD IRr5,r1,r3 Recalling Pipelining Recalling Pipelining What is a potential Problem with von Neumann Architecture? Harvard architecture address data memory data PC CPU address program memory data von Neumann vs. Harvard Harvard can’t use self-modifying code. Harvard allows two simultaneous memory fetches. Most DSPs (e.g Blackfin from ADI) use Harvard architecture for streaming data: greater memory bandwidth. different memory bit depths between instruction and data. more predictable bandwidth. Today’s Processors Harvard or von Neumann? RISC vs. CISC Complex instruction set computer (CISC): many addressing modes; many operations. Reduced instruction set computer (RISC): load/store; pipelinable instructions. Instruction set characteristics Fixed vs. variable length. Addressing modes. Number of operands. Types of operands. Tensilica Xtensa RISC based variable length But not CISC Programming model Programming model: registers visible to the programmer. Some registers are not visible (IR). Multiple implementations Successful architectures have several implementations: varying clock speeds; different bus widths; different cache sizes, associativities, configurations; local memory, etc. -

V850ES/SA2, V850ES/SA3 32-Bit Single-Chip Microcontrollers

To our customers, Old Company Name in Catalogs and Other Documents On April 1st, 2010, NEC Electronics Corporation merged with Renesas Technology Corporation, and Renesas Electronics Corporation took over all the business of both companies. Therefore, although the old company name remains in this document, it is a valid Renesas Electronics document. We appreciate your understanding. Renesas Electronics website: http://www.renesas.com April 1st, 2010 Renesas Electronics Corporation Issued by: Renesas Electronics Corporation (http://www.renesas.com) Send any inquiries to http://www.renesas.com/inquiry. Notice 1. All information included in this document is current as of the date this document is issued. Such information, however, is subject to change without any prior notice. Before purchasing or using any Renesas Electronics products listed herein, please confirm the latest product information with a Renesas Electronics sales office. Also, please pay regular and careful attention to additional and different information to be disclosed by Renesas Electronics such as that disclosed through our website. 2. Renesas Electronics does not assume any liability for infringement of patents, copyrights, or other intellectual property rights of third parties by or arising from the use of Renesas Electronics products or technical information described in this document. No license, express, implied or otherwise, is granted hereby under any patents, copyrights or other intellectual property rights of Renesas Electronics or others. 3. You should not alter, modify, copy, or otherwise misappropriate any Renesas Electronics product, whether in whole or in part. 4. Descriptions of circuits, software and other related information in this document are provided only to illustrate the operation of semiconductor products and application examples. -

Hierarchical Roofline Analysis for Gpus: Accelerating Performance

Hierarchical Roofline Analysis for GPUs: Accelerating Performance Optimization for the NERSC-9 Perlmutter System Charlene Yang, Thorsten Kurth Samuel Williams National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center Computational Research Division Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Berkeley, CA 94720, USA Berkeley, CA 94720, USA fcjyang, [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—The Roofline performance model provides an Performance (GFLOP/s) is bound by: intuitive and insightful approach to identifying performance bottlenecks and guiding performance optimization. In prepa- Peak GFLOP/s GFLOP/s ≤ min (1) ration for the next-generation supercomputer Perlmutter at Peak GB/s × Arithmetic Intensity NERSC, this paper presents a methodology to construct a hi- erarchical Roofline on NVIDIA GPUs and extend it to support which produces the traditional Roofline formulation when reduced precision and Tensor Cores. The hierarchical Roofline incorporates L1, L2, device memory and system memory plotted on a log-log plot. bandwidths into one single figure, and it offers more profound Previously, the Roofline model was expanded to support insights into performance analysis than the traditional DRAM- the full memory hierarchy [2], [3] by adding additional band- only Roofline. We use our Roofline methodology to analyze width “ceilings”. Similarly, additional ceilings beneath the three proxy applications: GPP from BerkeleyGW, HPGMG Roofline can be added to represent performance bottlenecks from AMReX, and conv2d from TensorFlow. In so doing, we demonstrate the ability of our methodology to readily arising from lack of vectorization or the failure to exploit understand various aspects of performance and performance fused multiply-add (FMA) instructions. bottlenecks on NVIDIA GPUs and motivate code optimizations. -

Testing and Validation of a Prototype Gpgpu Design for Fpgas Murtaza Merchant University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2013 Testing and Validation of a Prototype Gpgpu Design for FPGAs Murtaza Merchant University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the VLSI and Circuits, Embedded and Hardware Systems Commons Merchant, Murtaza, "Testing and Validation of a Prototype Gpgpu Design for FPGAs" (2013). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1012. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1012 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TESTING AND VALIDATION OF A PROTOTYPE GPGPU DESIGN FOR FPGAs A Thesis Presented by MURTAZA S. MERCHANT Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ELECTRICAL AND COMPUTER ENGINEERING February 2013 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering © Copyright by Murtaza S. Merchant 2013 All Rights Reserved TESTING AND VALIDATION OF A PROTOTYPE GPGPU DESIGN FOR FPGAs A Thesis Presented by MURTAZA S. MERCHANT Approved as to style and content by: _________________________________ Russell G. Tessier, Chair _________________________________ Wayne P. Burleson, Member _________________________________ Mario Parente, Member ______________________________ C. V. Hollot, Department Head Electrical and Computer Engineering ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To begin with, I would like to sincerely thank my advisor, Prof. Russell Tessier for all his support, faith in my abilities and encouragement throughout my tenure as a graduate student. -

Computer Organization & Architecture Eie

COMPUTER ORGANIZATION & ARCHITECTURE EIE 411 Course Lecturer: Engr Banji Adedayo. Reg COREN. The characteristics of different computers vary considerably from category to category. Computers for data processing activities have different features than those with scientific features. Even computers configured within the same application area have variations in design. Computer architecture is the science of integrating those components to achieve a level of functionality and performance. It is logical organization or designs of the hardware that make up the computer system. The internal organization of a digital system is defined by the sequence of micro operations it performs on the data stored in its registers. The internal structure of a MICRO-PROCESSOR is called its architecture and includes the number lay out and functionality of registers, memory cell, decoders, controllers and clocks. HISTORY OF COMPUTER HARDWARE The first use of the word ‘Computer’ was recorded in 1613, referring to a person who carried out calculation or computation. A brief History: Computer as we all know 2day had its beginning with 19th century English Mathematics Professor named Chales Babage. He designed the analytical engine and it was this design that the basic frame work of the computer of today are based on. 1st Generation 1937-1946 The first electronic digital computer was built by Dr John V. Atanasoff & Berry Cliford (ABC). In 1943 an electronic computer named colossus was built for military. 1946 – The first general purpose digital computer- the Electronic Numerical Integrator and computer (ENIAC) was built. This computer weighed 30 tons and had 18,000 vacuum tubes which were used for processing. -

The Microarchitecture of the Pentium 4 Processor

The Microarchitecture of the Pentium 4 Processor Glenn Hinton, Desktop Platforms Group, Intel Corp. Dave Sager, Desktop Platforms Group, Intel Corp. Mike Upton, Desktop Platforms Group, Intel Corp. Darrell Boggs, Desktop Platforms Group, Intel Corp. Doug Carmean, Desktop Platforms Group, Intel Corp. Alan Kyker, Desktop Platforms Group, Intel Corp. Patrice Roussel, Desktop Platforms Group, Intel Corp. Index words: Pentium® 4 processor, NetBurst™ microarchitecture, Trace Cache, double-pumped ALU, deep pipelining provides an in-depth examination of the features and ABSTRACT functions of the Intel NetBurst microarchitecture. This paper describes the Intel® NetBurst™ ® The Pentium 4 processor is designed to deliver microarchitecture of Intel’s new flagship Pentium 4 performance across applications where end users can truly processor. This microarchitecture is the basis of a new appreciate and experience its performance. For example, family of processors from Intel starting with the Pentium it allows a much better user experience in areas such as 4 processor. The Pentium 4 processor provides a Internet audio and streaming video, image processing, substantial performance gain for many key application video content creation, speech recognition, 3D areas where the end user can truly appreciate the applications and games, multi-media, and multi-tasking difference. user environments. The Pentium 4 processor enables real- In this paper we describe the main features and functions time MPEG2 video encoding and near real-time MPEG4 of the NetBurst microarchitecture. We present the front- encoding, allowing efficient video editing and video end of the machine, including its new form of instruction conferencing. It delivers world-class performance on 3D cache called the Execution Trace Cache. -

Parallel Computer Architecture

Parallel Computer Architecture Introduction to Parallel Computing CIS 410/510 Department of Computer and Information Science Lecture 2 – Parallel Architecture Outline q Parallel architecture types q Instruction-level parallelism q Vector processing q SIMD q Shared memory ❍ Memory organization: UMA, NUMA ❍ Coherency: CC-UMA, CC-NUMA q Interconnection networks q Distributed memory q Clusters q Clusters of SMPs q Heterogeneous clusters of SMPs Introduction to Parallel Computing, University of Oregon, IPCC Lecture 2 – Parallel Architecture 2 Parallel Architecture Types • Uniprocessor • Shared Memory – Scalar processor Multiprocessor (SMP) processor – Shared memory address space – Bus-based memory system memory processor … processor – Vector processor bus processor vector memory memory – Interconnection network – Single Instruction Multiple processor … processor Data (SIMD) network processor … … memory memory Introduction to Parallel Computing, University of Oregon, IPCC Lecture 2 – Parallel Architecture 3 Parallel Architecture Types (2) • Distributed Memory • Cluster of SMPs Multiprocessor – Shared memory addressing – Message passing within SMP node between nodes – Message passing between SMP memory memory nodes … M M processor processor … … P … P P P interconnec2on network network interface interconnec2on network processor processor … P … P P … P memory memory … M M – Massively Parallel Processor (MPP) – Can also be regarded as MPP if • Many, many processors processor number is large Introduction to Parallel Computing, University of Oregon,