Exploring the Development of a Strategic Communication on P/CVE in Albania: a Research Based Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloads/Reports/2016/Pdf/BTI 2016 Kosova.Pdf

Tourism governance in post-war transition: The case of Kosova REKA, Shqiperim Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/24197/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/24197/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. "Tourism governance in post-war transition: the case of Kosova" Shqiperim Reka A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2017 Abstract The aim of this research study was to examine tourism governance in post-war transition with specific reference to the influence of political, economic and social factors, institutional arrangements, collaboration and power relations. Within this context, a crucial objective was to assess the role of mindset. Reviewing the literature in relation to the key concepts, it was discovered that research tends to focus on political and economic transition, whereas the social dimension, despite its importance, is largely neglected. Similarly, tourism governance has been overlooked in studies of tourism in post-war transition. Furthermore, the literature on tourism governance rarely takes the issue of mindset into account. To address these gaps in knowledge, a qualitative research approach was applied to study tourism governance in post-war transitional Kosova. -

Regjistri I Koleksioneve Ex Situ Të Bankës Gjenetike

UNIVERSITETI BUJQËSOR I TIRANËS INSTITUTI I RESURSEVE GJENETIKE TË BIMËVE REGJISTRI I KOLEKSIONEVE EX SITU TË BANKËS GJENETIKE Tiranë, 2017 UNIVERSITETI BUJQËSOR I TIRANËS INSTITUTI I RESURSEVE GJENETIKE TË BIMËVE REGJISTRI I KOLEKSIONEVE EX SITU TË BANKËS GJENETIKE Përgatiti: B. Gixhari Botim i Institutit të Resurseve Gjenetike të Bimëve http://qrgj.org Tiranë, 2017 Regjistri i “KOLEKSIONEVE EX SITU” të Bankës Gjenetike është hartuar në kuadër të informimit të publikut të interesuar për Resurset Gjenetike të Bimëve në Shqipëri. Regjistri përmban informacione për gjermoplazmën bimore të grumbulluar/ koleksionuar gjatë viteve në pjesë të ndryshme të Shqipërisë dhe që ruhet jashtë vendorigjinës së tyre (ex situ) nga Banka Gjenetike Shqiptare. Në të dhënat e paraqitura në këtë regjistër janë treguesit (deskriptorët) e domosdoshëm të pasaportës së aksesioneve të bimëve të koleksionuara si: numri i aksesionit (ACCENUMB), numri i koleksionimit (COLLNUMB), kodi i koleksionimit (COLLCODE), emërtimi i pranuar taksonomik (TaxonName_Accepted), emri i aksesionit (ACCENAME), data e pranimit (ACQDATE), vendi i origjinës (ORIGCTY), vendi i koleksionimit (COLLSITE), gjerësia gjeografike (LATITUDE), gjatësia gjeografike (LONGITUTE), lartësia mbi nivelin e detit (ELEVATION) dhe data e koleksionimit (COLLDATE). Në koleksionet në ruajtje ex situ përfshihen aksesione të bimëve të kultivuara, aksesione të formave bimore lokale të njohura si varietete të vjetër të fermerit ose landrace, aksesione të pemëve frutore, të bimëve foragjere, bimëve industriale, bimëve mjekësore dhe aromatike dhe të bimëve të egra. Pjesa më e madhe e gjermoplazmës që ruhet në formën ex situ i përket formave të vjetra lokale ose varietetet e fermerit, të njohura për vlerat e tyre kryesisht cilësore, që janë përdorur në bujqësinë shqiptare dekada më parë, por që aktualisht përdoren në sipërfaqe të kufizuara ose nuk përdoren më në strukturën e bujqësisë intensive. -

The First Illyrian War: a Study in Roman Imperialism

The First Illyrian War: A Study in Roman Imperialism Catherine A. McPherson Department of History and Classical Studies McGill University, Montreal February, 2012 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts ©Catherine A. McPherson, 2012. Table of Contents Abstract ……………………………………………….……………............2 Abrégé……………………………………...………….……………………3 Acknowledgements………………………………….……………………...4 Introduction…………………………………………………………………5 Chapter One Sources and Approaches………………………………….………………...9 Chapter Two Illyria and the Illyrians ……………………………………………………25 Chapter Three North-Western Greece in the Later Third Century………………………..41 Chapter Four Rome and the Outbreak of War…………………………………..……….51 Chapter Five The Conclusion of the First Illyrian War……………….…………………77 Conclusion …………………………………………………...…….……102 Bibliography……………………………………………………………..104 2 Abstract This paper presents a detailed case study in early Roman imperialism in the Greek East: the First Illyrian War (229/8 B.C.), Rome’s first military engagement across the Adriatic. It places Roman decision-making and action within its proper context by emphasizing the role that Greek polities and Illyrian tribes played in both the outbreak and conclusion of the war. It argues that the primary motivation behind the Roman decision to declare war against the Ardiaei in 229 was to secure the very profitable trade routes linking Brundisium to the eastern shore of the Adriatic. It was in fact the failure of the major Greek powers to limit Ardiaean piracy that led directly to Roman intervention. In the earliest phase of trans-Adriatic engagement Rome was essentially uninterested in expansion or establishing a formal hegemony in the Greek East and maintained only very loose ties to the polities of the eastern Adriatic coast. -

Segmentet Rrugore Të Parashikuara Nga Bashkitë Për

SEGMENTET RRUGORE TË PARASHKIKUARA NGA BASHKITE PËR RIKONSTRUKSION/SISTEMIM NË PLANIN E BUXHETIT 2018 BASHKIA TIRANË Rehabilitimi Sheshi 1 “Kont Urani” Rehabilitimi Sheshi 2 Kafe “Flora” Rehabilitimi Sheshi 3 Blloku “Partizani” Rehabilitimi Sheshi 4 Sheshi “Çajupi” Rehabilitimi Sheshi 5 Stadiumi “Selman Stermasi” Rehabilitimi Sheshi 6 Perballe shkollës “Besnik Sykja” Rehabilitimi Sheshi 7 Pranë “Selvisë” Rehabilitimi Sheshi 8 “Medreseja” Rehabilitimi Sheshi 9 pranë tregut Industrial Rehabilitimi Sheshi 10 Laprakë Rehabilitimi Sheshi 11 Sheshi “Kashar” Rikonstruksioni i rruges Mihal Grameno dhe degezimit te rruges Budi - Depo e ujit (faza e dyte) Ndertim i rruges "Danish Jukniu" Rikonstruksioni i Infrastruktures sebllokut qe kufizohet nga rruga Endri Keko, Sadik Petrela dhe i trotuareve dhe rruges "Hoxha Tahsim" dhe Xhanfize Keko Rikonstruksioni i Infrastruktures rrugore te bllokut kufizuar nga rruga Njazi Meka - Grigor Perlecev-Niko Avrami -Spiro Cipi - Fitnetet Rexha - Myslym Keta -Skeneder Vila dhe lumi i Tiranes Rikonstruksion i rruges " Imer Ndregjoni " Rikonstruksioni i rruges "Dhimiter Shuteriqi" Rikonstruksioni i infrastruktures rrugore te bllokut kufizuar nga rruget Konferenca e Pezes - 3 Deshmoret dhe rruga Ali Jegeni Rikonstruksioni i rruges Zall - Bastarit (Ura Zall Dajt deri ne Zall Bastar) - Loti II. Rikonstruksioni i infrastruktures rrugore te bllokut qe kufizohet nga rruga Besa - Siri Kodra - Zenel Bastari - Haki Rexhep Kodra (perfshin dhe rrugen tek Nish Kimike) Rikonstruksioni i infrastruktures rrugore te bllokut qe kufizohet -

Albanian Catholic Bulletin Buletini Katholik Shqiptar

ISSN 0272 -7250 ALBANIAN CATHOLIC BULLETIN PUBLISHED PERIODICALLY BY THE ALBANIAN CATHOLIC INFORMATION CENTER Vol.3, No. 1&2 P.O. BOX 1217, SANTA CLARA, CA 95053, U.S.A. 1982 BULETINI d^M. jpu. &CU& #*- <gP KATHOLIK Mother Teresa's message to all Albanians SHQIPTAR San Francisco, June 4, 1982 ALBANIAN CATHOLIC PUBLISHING COUNCIL: ZEF V. NEKAJ, JAK GARDIN, S.J., PJETER PAL VANI, NDOC KELMENDI, S.J., BAR BULLETIN BARA KAY (Assoc. Editor), PALOK PLAKU, RAYMOND FROST (Assoc. Editor), GJON SINISHTA (Editor), JULIO FERNANDEZ Volume III No.l&2 1982 (Secretary), and LEO GABRIEL NEAL, O.F.M., CONV. (President). In the past our Bulletin (and other material of information, in cluding the book "The Fulfilled Promise" about religious perse This issue has been prepared with the help of: STELLA PILGRIM, TENNANT C. cution in Albania) has been sent free to a considerable number WRIGHT, S.J., DAVE PREVITALE, JAMES of people, institutions and organizations in the U.S. and abroad. TORRENS, S.J., Sr. HENRY JOSEPH and Not affiliated with any Church or other religious or political or DANIEL GERMANN, S.J. ganization, we depend entirely on your donations and gifts. Please help us to continue this apostolate on behalf of the op pressed Albanians. STRANGERS ARE FRIENDS News, articles and photos of general interest, 100-1200 words WE HAVEN'T MET of length, on religious, cultural, historical and political topics about Albania and its people, may be submitted for considera tion. No payments are made for the published material. God knows Please enclose self-addressed envelope for return. -

Lista E Plotë Të Emrave Të Përfituesve Të Lejeve Të Legalizimit

Petrit Shemsi Potja Farke Falenderim Ferhat Vrapi Vaqarr Shpetim Fejz Hasa Dajt Asrtit Avdyl Hima Vaqarr Hajredin Rasim Kasami Farke Dritan Ahmet Kukli Berzhite Halim Hysen Vraja Zall-Herr Arjanit Ramazan Bunoca Dajt Muhamed Ibrahim Allmuca Baldushk Xhemile Bajram Rruga Ndroq Lulzim Rifat Kuka Dajt Gezim Log Kazhaja Baldushk Flamur Hamdi Alimadhi Krrabe Arben Cen Gresa Kashar Ilmije Hekuran Shehu Kashar Agron Kadri Sulaj Kashar Shukri Ali Brija Kashar Lulzim Haki Rama Baldushk Petrit Ali Kacollja Baldushk Diturie Sabri Leci Baldushk Ermir Ali Aliu Berzhite Sulejman Fadil Kacollja Baldushk Bashkim Bedri Plaku Kashar Fredi Hajdar Pashollari Kashar Selami Haki Gaxholli Kashar Tomorr Zef Vataj Vaqarr Majlinda Jonuz Duda Kashar Xhavit Xhemal Aga Vaqarr Erind Ruzhdi Sefa Vaqarr Bashkim Mahmud Grifsha Zall-Herr Jonuz Jusuf Peqini Farke Hasan Beqir Hida Zall-Herr Hazbi Mal Sula Zall-Herr Shefqet Bajram Peca Kashar Sinan Muharrem Dedja Farke Masar Mehdi Selmani Farke Nasip Rexhep Shehu Kashar Vangjel,Aleko Jorgo Vasiliu Peze Bilal Refik Cela Farke Naim Hashim Osmanaj Farke Ruzhdi Adem Dapi Krrabe Musa Banush Dedja Krrabe Halil Ibrahim Potka Kashar Hajdar Zyber Sula Petrele Shkelqim Daut Ibra Baldushk Arben Veli Vraja Zall-Herr Qamil Xhemal Meta Zall-Herr Reshit Musa Gurra Petrele Ruzhdi Hasan Tota Kashar Sabrije Ramazan Alldervishi Farke Haki Sinan Dedja Farke Maliq Besim Turshilla Kashar Arjan Mustaf Mustafaj Farke Skender Sulejman Shehi Farke Ali Shahin Mamaj Kashar Merkur Qamil Vodha Farke Dervish Islam Hakcani Farke Bashkim Imer Muho Kashar -

EUROPE a Albania • National Historical Museum – Tirana, Albania

EUROPE A Albania • National Historical Museum – Tirana, Albania o The country's largest museum. It was opened on 28 October 1981 and is 27,000 square meters in size, while 18,000 square meters are available for expositions. The National Historical Museum includes the following pavilions: Pavilion of Antiquity, Pavilion of the Middle Ages, Pavilion of Renaissance, Pavilion of Independence, Pavilion of Iconography, Pavilion of the National Liberation Antifascist War, Pavilion of Communist Terror, and Pavilion of Mother Teresa. • Et'hem Bey Mosque – Tirana, Albania o The Et’hem Bey Mosque is located in the center of the Albanian capital Tirana. Construction was started in 1789 by Molla Bey and it was finished in 1823 by his son Ethem Pasha (Haxhi Ethem Bey), great- grandson of Sulejman Pasha. • Mount Dajt – Tirana, Albania o Its highest peak is at 1,613 m. In winter, the mountain is often covered with snow, and it is a popular retreat to the local population of Tirana that rarely sees snow falls. Its slopes have forests of pines, oak and beech. Dajti Mountain was declared a National Park in 1966, and has since 2006 an expanded area of about 29,384 ha. It is under the jurisdiction and administration of Tirana Forest Service Department. • Skanderbeg Square – Tirana, Albania o Skanderbeg Square is the main plaza of Tirana, Albania named in 1968 after the Albanian national hero Skanderbeg. A Skanderbeg Monument can be found in the plaza. • Skanderbeg Monument – Skanderberg Square, Tirana, Albania o The monument in memory of Skanderbeg was erected in Skanderbeg Square, Tirana. -

Datë 06.03.2021

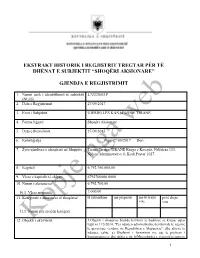

EKSTRAKT HISTORIK I REGJISTRIT TREGTAR PËR TË DHËNAT E SUBJEKTIT “SHOQËRI AKSIONARE” GJENDJA E REGJISTRIMIT 1. Numri unik i identifikimit të subjektit L72320033P (NUIS) 2. Data e Regjistrimit 27/09/2017 3. Emri i Subjektit UJËSJELLËS KANALIZIME TIRANË 4. Forma ligjore Shoqëri Aksionare 5. Data e themelimit 27/09/2017 6. Kohëzgjatja Nga: 27/09/2017 Deri: 7. Zyra qëndrore e shoqërisë në Shqipëri Tirane Tirane TIRANE Rruga e Kavajës, Ndërtesa 133, Njësia Administrative 6, Kodi Postar 1027 8. Kapitali 6.792.760.000,00 9. Vlera e kapitalit të shlyer: 6792760000.0000 10. Numri i aksioneve: 6.792.760,00 10.1 Vlera nominale: 1.000,00 11. Kategoritë e aksioneve të shoqërisë të zakonshme me përparësi me të drejte pa të drejte vote vote 11.1 Numri për secilën kategori 12. Objekti i aktivitetit: 1.Objekti i shoqerise brenda territorit te bashkise se krijuar sipas ligjit nr.l 15/2014, "Per ndarjen administrative-territoriale te njesive te qeverisjes vendore ne Republiken e Shqiperise", dhe akteve te ndarjes, eshte: a) Sherbimi i furnizimit me uje te pijshem i konsumatoreve dhe shitja e tij; b)Mirembajtja e sistemit/sistemeve 1 te furnizimit me ujë te pijshem si dhe të impianteve te pastrimit te tyre; c)Prodhimi dhe/ose blerja e ujit per plotesimin e kerkeses se konsumatoreve; c)Shërbimi i grumbullimit, largimit dhe trajtimit te ujerave te ndotura; d)Mirembajtja e sistemeve te ujerave te ndotura, si dhe të impianteve të pastrimit të tyre. 2.Shoqeria duhet të realizojë çdo lloj operacioni financiar apo tregtar që lidhet direkt apo indirect me objektin e saj, brenda kufijve tè parashikuar nga legjislacioni në fuqi. -

Economic Bulletin Economic Bulletin September 2007

volume 10 volume 10 number 3 number 3 September 2007 Economic Bulletin Economic Bulletin September 2007 E C O N O M I C September B U L L E T I N 2 0 0 7 B a n k o f A l b a n i a PB Bank of Albania Bank of Albania 1 volume 10 volume 10 number 3 number 3 September 2007 Economic Bulletin Economic Bulletin September 2007 Opinions expressed in these articles are of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Bank of Albania. If you use data from this publication, you are requested to cite the source. Published by: Bank of Albania, Sheshi “Skënderbej”, Nr.1, Tirana, Albania Tel.: 355-4-222230; 235568; 235569 Fax.: 355-4-223558 E-mail: [email protected] www.bankofalbania.org Printed by: Bank of Albania Printing House Printed in: 360 copies 2 Bank of Albania Bank of Albania 3 volume 10 volume 10 number 3 number 3 September 2007 Economic Bulletin Economic Bulletin September 2007 C O N T E N T S Quarterly review of the Albanian economy over the third quarter of 2007 7 Speech by Mr. Ardian Fullani, Governor of the Bank of Albania At the signing of the Memorandum of Understanding with the Competition Authority. Tirana, 17 July 2007 41 Speech by Mr. Ardian Fullani, Governor of the Bank of Albania At the seminar “Does Central Bank Transparency Reduce Interest Rates?” Hotel “Tirana International”. August 22, 2007 43 Speech by Mr. Ardian Fullani, Governor of the Bank of Albania At the conference organized by the Central Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina September 13, 2007 46 Speech by Mr. -

Dokumenti I Strategjisë Së Zhvillimit Të Territorit Të Bashkisë Elbasan

BASHKIA ELBASAN DREJTORIA E PLANIFIKIMIT TË TERRITORIT Adresa: Bashkia Elbasan, Rr. “Q. Stafa”, Tel.+355 54 400152, e-mail: [email protected], web: www.elbasani.gov.al DOKUMENTI I STRATEGJISË SË ZHVILLIMIT TË TERRITORIT TË BASHKISË ELBASAN MIRATOHET KRYETARI I K.K.T Z. EDI RAMA MINISTRIA E ZHVILLIMIT URBAN Znj. EGLANTINA GJERMENI KRYETARI I KËSHILLIT TË BASHKISË Z. ALTIN IDRIZI KRYETARI I BASHKISË Z. QAZIM SEJDINI Miratuar me Vendim të Këshillit të Bashkisë Elbasan Nr. ___Datë____________ Miratuar me Vendim të Këshillit Kombëtar të Territorit Nr. 1 Datë 29/12/2016 Përgatiti Bashkia Elbasan Mbështeti Projekti i USAID për Planifikimin dhe Qeverisjen Vendore dhe Co-PLAN, Instituti për Zhvillimin e Habitatit 1 TABELA E PËRMBAJTJES AUTORËSIA DHE KONTRIBUTET ........................................................................................ 6 SHËNIM I RËNDËSISHËM ....................................................................................................... 7 I. SFIDAT E BASHKISË ELBASAN ....................................................................................... 11 1.1 Tendencat kryesore të zhvillimit të pas viteve `90të ......................................................................................... 13 1.1.1 Policentrizmi ............................................................................................................................................. 15 1.2 Territori dhe mjedisi ........................................................................................................................................ -

GTZ-Regional Sustainable Development Tirana 2002

GTZ GmbH German Technical Cooperation, Eschborn Institute of Ecological and Regional Development (IOER), Dresden Towards a Sustainable Development of the Tirana – Durres Region Regional Development Study for the Tirana – Durres Region: Development Concept (Final Draft) Tirana, February 2002 Regional Development Study Tirana – Durres: Development Concept 1 Members of the Arqile Berxholli, Academy of Sci- Stavri Lami, Hydrology Research Working Group ence Center and authors of Vladimir Bezhani, Ministry of Public Perparim Laze, Soil Research In- studies Works stitute Salvator Bushati, Academy of Sci- Fioreta Luli, Real Estate Registra- ence tion Project Kol Cara, Soil Research Institute Irena Lumi, Institute of Statistics Gani Deliu, Tirana Regional Envi- Kujtim Onuzi, Institute of Geology ronmental Agency Arben Pambuku, Civil Geology Ali Dedej, Transport Studies Insti- Center tute Veli Puka, Hydrology Research Llazar Dimo, Institute of Geology Center Ilmi Gjeci, Chairman of Maminas Ilir Rrembeci, Regional Develop- Commune ment Agency Fran Gjini, Mayor of Kamza Mu- Thoma Rusha, Ministry of Eco- nicipality, nomic Cooperation and Trade Farudin Gjondeda, Land and Wa- Skender Sala, Center of Geo- ter Institute graphical Studies Elena Glozheni, Ministry of Public Virgjil Sallabanda, Transport Works Foundation Naim Karaj, Chairman of National Agim Selenica, Hydro- Commune Association Meteorological Institute Koco Katundi, Hydraulic Research Agron Sula , Adviser of the Com- Center mune Association Siasi Kociu, Seismological Institute Mirela Sula, -

Strategjia E Zhvillimit Të Qendrueshëm Bashkia Tiranë 2018

STRATEGJIA E ZHVILLIMIT TË QENDRUESHËM TË BASHKISË TIRANË 2018 - 2022 DREJTORIA E PËRGJITSHME E PLANIFIKIMIT STRATEGJIK DHE BURIMEVE NJERËZORE BASHKIA TIRANË Tabela e Përmbajtjes Përmbledhje Ekzekutive............................................................................................................................11 1. QËLLIMI DHE METODOLOGJIA...............................................................................................................12 1.1 QËLLIMI...........................................................................................................................................12 1.2 METODOLOGJIA..............................................................................................................................12 1.3 PARIMET UDHËHEQËSE..................................................................................................................14 2. TIRANA NË KONTEKSTIN KOMBËTAR DHE NDËRKOMBËTAR.................................................................15 2.1 BASHKËRENDIMI ME POLITIKAT DHE PLANET KOMBËTARE...........................................................15 2.2 KONKURUESHMËRIA DHE INDIKATORËT E SAJ...............................................................................13 2.2.1 Burimet njerëzore dhe cilësia e jetës......................................................................................13 2.2.2 Mundësitë tregtare dhe potenciali prodhues.........................................................................14 2.2.3 Transport...............................................................................................................................15