Green All the Way and Lots More!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bluebell Railway Education Department Along the Line

BLUEBELL RAILWAY EDUCATION DEPARTMENT ALONG THE LINE FOR SCHOOLS SHEFFIELD PARK STATION 1. Approaching the station buildings along the drive, the picnic area can be seen to the right, adjacent to the River Ouse, where lunch can be taken. The river is little more than a stream today but it was once navigable from the sea at Newhaven to just short of Balcombe Viaduct – on the London to Brighton main line between Haywards Heath and Balcombe. The 11 million bricks used to construct the viaduct were transported up river from Lewes by barge. 2. The station is built in the Queen Anne country architectural style, a style used at all stations on the line and is painted in the colours of the line's initial operators, the London Brighton and South Coast Railway. The year in which the line opened – 1892 -can be found in the decorative plasterwork on the front of the station building. Passengers enter the station via the booking hall and purchase their old fashioned Edmondson cardboard tickets from the booking office. The station was originally lit by oil lamps but is now lit by a mix of evocative gas lighting and more modern electric lights. It sits astride the Greenwich Meridian, the exact (Photo: Bluebell Archives) location being marked by a plaque at the north end of platform 1. 3. The Railway houses and maintains its fleet of mainly steam locomotives at the station - currently it has some thirty engines in stock although only ten or so are in service at any given time – they need a boiler inspection and a new certificate every ten years. -

Preserved Coaching Stock of British Railways

PRESERVED COACHING STOCK OF BRITISH RAILWAYS AMENDMENT SHEET NUMBER 23 December 1997/January 1998/February 1998 LOCOMOTIVE HAULED COACHING STOCK 1) Additions a) Southern Railway Stock B 210 083618 Isle of Wight Steam Railway PMV 1156 DS156 Ebberston Station near Pickering PMV 1193 DS166 Bluebell Railway PMV 1350 DS1385 Gloucestershire-Warwickshire Railway PMV 1626 DB975568 Bristol Industrial Museum CCT 2373 DS70239 Bluebell Railway b) British Rail Mark 1 Passenger Carrying Coaching Stock RB 1672 Gloucestershire-Warwickshire Railway BCK 21273 DB977384 South Yorkshire Railway SK 24157 DB975162 Kent & East Sussex Railway BSK 34136 DB975459 Battlefield Steam Railway BSK 34368 DB975476 Spa Valley Railway BSK 34414 DB975128 Severn Valley Railway BSK 34698 DB977383 Mid-Norfolk Railway c) British Rail Mark 2 Passenger Carrying Coaching Stock BSO 9414 Spa Valley Railway d) British Rail Non Passenger Carrying Coaching Stock POS 80301 Great Central Railway CCT 94142 024672 Battlefield Steam Railway CCT 94772 DB977113 Kent & East Sussex Railway Body only remains 2) Deletions a) Southern Railway Stock TK 1020 DS70134 Broken up on site at the Kent & East Sussex Railway BUO 4438 7920 DB975279 Broken up on site at the Kent & East Sussex Railway 3) Movements a) Pullman Car Company Stock 136 MAID OF KENT MoD BAD Kineton b) Great Western Railway Stock MILK 2835 DW2835 Gloucestershire – Warwickshire Railway c) Southern Railway Stock LSWR/SR BTK 3204 DS70085 South Devon Railway under frame only remains BTK 1346 DS70201 083181 Rother Valley Railway BY 440 Rother Valley Railway PMV 1248 ADS161 Rother Valley Railway PMV 177 2012 ADS1035 Rother Valley Railway d) London, Midland & Scottish Railway Stock BG 31407 XDB977037 West Somerset Railway BGZ 32978 East Lancashire Railway e) London & North Eastern Railway Stock TK 3849 12961 DE320946 Kirkby Stephen East Station f) British Rail Mark 1 Passenger Carrying Coaching Stock SLF 2110 Llangollen Railway SLF 2127 Stored at Steamtown Railway Centre for Great Scottish & Western Railway Co. -

Jclettersno Heading

.HERITAGE RAILWAY ASSOCIATION. Mark Garnier MP (2nd left) presents the HRA Annual Award (Large Groups) to members of the Isle of Wight Steam Railway and the Severn Valley Railway, joint winners of the award. (Photo. Gwynn Jones) SIDELINES 143 FEBRUARY 2016 WOLVERHAMPTON LOW LEVEL STATION COMES BACK TO LIFE FOR HRA AWARDS NIGHT. The Grand Station banqueting centre, once the GWR’s most northerly broad gauge station, came back to life as a busy passenger station when it hosted the Heritage Railway Association 2015 Awards Night. The HRA Awards recognise a wide range of achievements and distinctions across the entire heritage railway industry, and the awards acknowledge individuals and institutions as well as railways. The February 6th event saw the presentation of awards in eight categories. The National Railway Museum and York Theatre Royal won the Morton’s Media (Heritage Railways) Interpretation Award, for an innovative collaboration that joined theatre with live heritage steam, when the Museum acted as a temporary home for the theatre company. The Railway Magazine Annual Award for Services to Railway Preservation was won by David Woodhouse, MBE, in recognition of his remarkable 60-year heritage railways career, which began as a volunteer on the Talyllyn Railway, and took him to senior roles across the heritage railways and tourism industry. The North Yorkshire Moors Railway won the Morton’s Media (Rail Express) Modern Traction Award, for their diesel locomotive operation, which included 160 days working for their Crompton Class 25. There were two winners of the Steam Railway Magazine Award. The Great Little Trains of North Wales was the name used by the judges to describe the Bala Lake Railway, Corris Railway, Ffestiniog & Welsh Highland Railway, Talyllyn Railway, Vale of Rheidol Railway and the Welshpool & Llanfair Railway. -

September 2020

The Bluebell Times A Newsletter for Bluebell Railway Members, Staff and Supporters September 2020 ‘Camelot’ and the Breakfast Belle crest Freshfield Bank, 16 August 2020 Photo: David Cable IN THIS ISSUE September started with some tremendous news for the railway, National Lottery Heritage Grant ............. 2 which was awarded a grant of £250,000 from the National Lottery Heritage Emergency Fund. The award, which was the highest sum ‘Tis the Season.......................................3 available, will be used to help sustain the Railway over the coming Autumn Offers ...................................... 4 months, and is a reward for the hard work of those people who Footplate Access Completes ASH Project . 5 prepared the application. The award comes on the back of the Railway’s own funding appeal, which has to date raised around Building the Buffer Stops in SteamWorks! 6 £390,000 from the generosity of our members, shareholders and VJ Day Memorial and the Bluebell Railway supporters. ........................................................... 8 Of course, the very existence of the Heritage Emergency Fund is a BROOSS .............................................. 9 reminder, if any were needed, that the Covid emergency is far from Five Minutes With ... Colin Tyson ........... 10 over, and the pressure on organisations such as the Bluebell Railway is A Closer Look at … Stowe ..................... 12 still very real. It is thus vital that the services we are able to run are as successful as possible. To that end it is very pleasing to see the rapid A Day in the Life of ... a Friend of Sheffield Park ................................................... 13 taKe-up of ticKets for our Christmas trains, including the new ‘SteamLights’ services – but now the challenge is to ensure that our ‘The Bluebell Railway’ Nameplate ......... -

The Tornado Telegraph Be Tornado’S Last Run out on the Main Line Boden Family for an Undisclosed Sum

THE TORNADO No. 54 August 2014 TELEGRAPH Jack Beeston Tornado passes Cullompton on the return leg of ‘The Devon Belle’. l DRIVER EXPERIENCE NEWS BRIEFS COURSES AT BARROW HILL Welcome - The A1 Steam Locomotive Trust, ... to issue No. 54 l ‘THE DEVON BELLE’ – On 25th in conjunction with Barrow Hill of The Tornado August, Tornado’s destination was Exeter. Roundhouse, is pleased to announce Telegraph. Tornado Starting down the winding Great Western that Tornado will be taking part in started the ‘Berks & Hants’ line, taking water at driver experience days on Tuesday month at the Newbury, the train then turned left on to 30th September, Wednesday 1st Bluebell Railway, the single track branch to Yeovil Pen Mill and Thursday 2nd October 2014. her fi rst visit since before using the spur to Yeovil Junction Opportunities to drive and fi re Tornado her epoch making arrival there are very rare indeed and places are with the fi rst inbound steam and joined the Southern Railway’s West strictly limited. You can fi nd full details tour since the railway was re- of England Main Line. Gaining Exeter via here. connected at east Grinstead. On Central Station, the train arrived at St. 25th August Tornado revisited the Davids for passengers to alight and enjoy l No. 61306 JOINS THE West Country with ‘The Devon the city for a few hours. PARTY - Retired businessman and Belle’ from London to Exeter – a The return run was over Whiteball, long-term London & North Eastern grand day out in less than perfect through Taunton to Castle Cary where the Railway enthusiast David Buck has weather! train re-joined the outward route. -

27/09/2019 Preserved Southern Railway Design

27/09/2019 PRESERVED SOUTHERN RAILWAY DESIGN COACHING STOCK PASSENGER CARRYING COACHING STOCK Page 1 THIRD with LAVATORY [non-gangwayed] TL Order: 801 Diagram: 31 Built: 1935 Design: LSWR Builder: Lancing Seats: 88T Restriction: 0 Body originally LSWR T 1228 built 1900. New underframe and lengthened 1935. 288 320 Bluebell Railway Body originally LSWR T built 1900. New underframe and lengthened 1935. Converted to Compressor Wagon in 1959 (bodywork removed) and to CCE 'Britannia' Rail Carrier in 1981. 328 353 DS70000 Isle of Wight Steam Railway Underframe only remains 'BRITANNIA' SECOND [non-gangwayed] S Order: Diagram: Built: 1962 Design: BR (S) Builder: Ashford/Eastleigh Seats: 120S Restriction: 4 Underframe from BR TSO 4378 the body of which was destroyed in 1957 Lewisham Accident . Nine compartment Second class glass-reinforced body fitted in 1962. Initially used in Lancing Works train numbered DS70200. Taken into BR stock as 1000 in Southern Railway Passenger Carrying Stock series and used on Hayling Island branch and 'Kenny Belle' trains. DS70200 1000 East Somerset Railway CORRIDOR THIRD TK Order: 709 Diagram: 2004 Built: 1934 Design: Maunsell Builder: Lancing/Eastleigh Seats: 48T Restriction: 0 Converted to BTU Staff & Tool Coach in 1962, subsequently used as Internal User at Selhurst Depot 1019 ADS70129 083607 Isle of Wight Steam Railway Underframe only remains OPEN THIRD TO Order: 761 Diagram: 2007 Built: 1935 Design: Maunsell Builder: Lancing/Eastleigh Seats: 56T Restriction: 4 Used as Internal User at ? 1309 081642 Bluebell Railway Order: 706 Diagram: 2005 Built: 1933 Design: Maunsell Builder: Lancing/Eastleigh Seats: 56T Restriction: 4 1323 used as Internal User at ?, subsequently converted to CM&EE Instruction Coach in 1967. -

BISC MINIBUSES Your FREE Transport Service

BISC MINIBUSES Your FREE Transport Service EXPLORE! Fall Term 2018 1 Take advantage of the FREE minibus service 7 days a week during term time. Our friendly and knowledgeable drivers Darren, Lynne, Libby and Katie will take you to local towns and villages, beaches, walks, tours, places of interest, volunteering opportunities and sports facilities. The minibus also links you to public transport buses and trains. HOW IT WORKS Monday through Thursday Minibuses mostly run to local towns for trains and public buses, shopping and banking, cinemas, sports facilities and volunteering opportunities. Friday through Sunday Get out and explore the local area. Each week there are minibus trips to various places, as well as railway station drops and pick-ups. WHAT YOU DO • Check out the weekly schedules and destination leaflets displayed at: Bader Hall Reception (plus destination leaflets) Castle Reception Online at: https://www.queensu.ca/bisc/current-students/getting-around/minibus/minibus- schedule (Plus, destination leaflets, maps of local towns, train and bus timetables) • The destination leaflets give you an idea of what there is to do, frequency of trips and how long it will take you to get there. • Choose the trips you want to take and sign up at Bader Hall Reception. Please also sign up for any special trips put on at your request. • Get on the bus at Castle Reception. • If you change your mind, take your name off the list so someone else can ride the bus in your place. • If you’d like to go somewhere specific on a particular day (journey distance no more than one hour away, please – check Google Maps), e-mail [email protected] by 5pm on the Tuesday of the week before, e.g. -

Whose Heritage Railway Is It? —A Study of Volunteer Motivation Geoff Goddin

Feature Heritage Railways (part 3) Whose Heritage Railway is It? —A Study of Volunteer Motivation Geoff Goddin This article explores the evolving role of shows volunteering in a more structured participation, but with the risk of my volunteers at two heritage railways in the and managed context, tasked with being uniquely sympathetic to UK. It analyses the characteristics and keeping the railway operating with focus organizational dilemmas3 . An motivations of volunteers1 and seeks to on aspects of customer service such as opportunity to conduct a telephone draw conclusions for management of punctuality, cleanliness, safety, and an interview with respondents was also heritage railways. array of ancillary services. A Swanage requested and ten provided their contact As heritage-railway operations have interviewee put it succinctly saying, ‘This numbers. grown in operational and financial is a business we are operating, we are no My approach was to characterize complexity over the past 50 years, so has longer playing trains.’ volunteers and their perceptions rather the part played by volunteer railway than pose problems for evaluation. Some workers. Rolt2 writing of the trials of of the results are summarized in Table 1. resurrecting the Talyllyn Railway in the Methodology early 1950s described a Boy’s Own comic spirit of adventure involving A themed questionnaire distributed to Preliminary Conclusions enthusiasm, ingenuity and a fair degree guards and other grades was used to of irresponsibility. Team spirit was built categorize volunteer characteristics, Do heritage railways face an by overcoming adversity in order to make personal motivations and views on aging volunteer workforce? (Q5) the railway run at all. -

Teachers Info Pack

BLUEBELL RAILWAY A. TEACHERS’ INFORMATION PACK Copyright of ‘Bluebell Railway plc’ May only be reproduced by teachers for educational purposes. Revised January 2015 www.bluebell-railway.co.uk Page 1 of 14 BLUEBELL RAILWAY TEACHERS’ INFORMATION PACK Contents 1. General Information 2. Facilities for School Visits 3. Safety Guidelines and Risk Assessment 4. History of the Line. 5. The Birth and Development of the Railway 6. Complementary Educational Activities Page 2 of 14 1. General Information Projects based on the Bluebell Railway can contribute towards all elements of the National Curriculum. 1/1 The Bluebell Railway is a single track standard gauge preserved railway based at Sheffield Park Station in East Sussex situated between Haywards Heath (7 miles) and Uckfield (8 miles). It runs for some 11 miles between Sheffield Park and East Grinsted with intermediate stations at stations at Horsted Keynes and Kingscote. 2/1 The railway’s older stations (not East Grinstead), its locomotives and rolling stock, cover a period of railway history from the 1880s to the 1950s and, as such, provides children with a unique insight into a way of life that has largely disappeared from Great Britain today. A way of life that was heavily dependent upon the railway both for personal transport and for the transport of goods. 3/1 Visits can be tailored to meet specific educational needs relating to the syllabus or to provide experience of specific events, such as wartime evacuation exercises. For younger children “Santa Special” services are provided during December. 4/1 Facilities available include:- Provision for disabled visitors Reserved accommodation on trains Toilets at the larger stations and on the trains Picnic areas and a dry area for eating lunch at the larger stations Refreshment facilities on trains, at Sheffield Park and Horsted Keynes stations Classroom seating up to 25 students Guided visits to booking offices, signal boxes, engine sheds, the footplate of a steam engine and to the new museum. -

Bluebell Railway

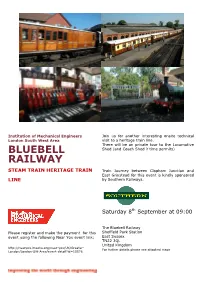

Institution of Mechanical Engineers Join us for another interesting onsite technical London South West Area visit to a heritage train line. There will be an private tour to the Locomotive Shed (and Coach Shed if time permits) BLUEBELL RAILWAY STEAM TRAIN HERITAGE TRAIN Train Journey between Clapham Junction and East Grinstead for this event is kindly sponsored LINE by Southern Railways. th Saturday 8 September at 09:00 The Bluebell Railway Please register and make the payment for this Sheffield Park Station event using the following Near You event link: East Sussex TN22 3QL United Kingdom http://nearyou.imeche.org/near-you/UK/Greater- For further details please see attached maps London/London-SW-Area/event-detail?id=15576 BLUEBELL RAILWAY STEAM TRAIN HERITAGE TRAIN LINE The Bluebell Railway is a heritage line running for 11 mi (17.7 km) along the border between East and West Sussex, England, run by the Bluebell Railway Preservation Society. It uses steam trains which operate between Sheffield Park and East Grinstead, with intermediate stations at Horsted Keynes & Kingscote. The first preserved standard gauge steam-operated passenger railway in the world to operate a public service, the society ran its first train on 7 August 1960, less than three years after the line from East Grinstead to Lewes had been closed by British Railways. On 23 March 2013, the Bluebell Railway commenced running through to its new East Grinstead terminus station. At East Grinstead there is a connection to the UK national rail network, the first connection of the Bluebell Railway to the national network in 50 years, since the Horsted Keynes – Haywards Heath line closed in 1963. -

Annual Report 2010 Page 2 Annual Report 2010

Annual Report 2010 Page 2 Annual Report 2010 Contents Contents .......................................................................................................................... 2 Foreword ......................................................................................................................... 5 Chairman‘s Report—David T Morgan MBE TD ............................................................... 6 Vice Chairman‘s Report - Mark Smith ........................................................................... 10 Vice President‘s-report Brian Simpson .......................................................................... 12 President-Lord Faulkner of Worcester .......................................................................... 13 Managing Director—David Woodhouse ........................................................................ 14 Finance Director—Andrew Goyns ................................................................................. 15 Company Secretary - Peter Ovenstone ........................................................................ 16 Sidelines / Broadlines and Press—John Crane............................................................. 17 Railway Press —Ian Smith ............................................................................................ 19 Small Groups—Ian Smith .............................................................................................. 20 General Meetings-Bill Askew ....................................................................................... -

Railways of Southern England Ramble

RAILWAYS OF SOUTHERN ENGLAND RAMBLE September 11 through 20, 2019, with an optional 3-day London extension Join us on this customized trip to ride the heritage railways, visit historic sites and experience the culture of southern England! RAMBLE HIGHLIGHTS DAY 1 Meet at and depart from the PHILADELPHIA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT for our group’s overnight, transatlantic flight to LONDON. DAY 2 (Breakfast & Dinner included today) Morning arrival in London. Board our charter motorcoach with our British guide and drive to Windsor for breakfast by the Thames and a tour of WINDSOR CASTLE. Drive to BATH. First of four overnight stays in Bath at the ABBEY HOTEL. DAY 3 (B) Visit the DIDCOT RAILWAY CENTRE, the former Great Western Railway’s historic engine shed and locomotive stabling facility. Afternoon visit at STEAM, the museum of the Great Western Railway. Second of four overnight stays in Bath. DAY 4 (B) Guided walking tour of BATH featuring the Royal Crescents and the Roman baths. Afternoon and evening at leisure. Third of four overnight stays in Bath. DAY 5 (B & D) Ride the rails of the Great Western Railway aboard the steam-hauled TORBAY EXPRESS, featuring premier dining service. Ferry to DARTMOUTH for a cruise on the River Dart on board the paddle steamer KINGSWEAR. Final night in Bath. DAY 6 (B, L & D) Ferry from Southampton to the Isle of Wight for a tour of Queen Victoria’s OSBORNE HOUSE and a ride on the ISLE OF WIGHT STEAM RAILWAY in restored rail carriages. Overnight in PORTSMOUTH at the MARRIOTT HOTEL. DAY 7 (B & L) Visit the HOLLYCOMBE STEAM IN THE COUNTRY, Britain’s largest collection of working steam.