DISASTER SALSA Linda A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hair's the Question*

Hair Transplant Forum International www.ISHRS.org March/April 2015 Hair’s the Question* Sara Wasserbauer, MD, FISHRS Walnut Creek, California, USA [email protected] *The questions presented by the author are not taken from the ABHRS item pool and accordingly will not be found on the ABHRS Certifying Examination. I got a new toy a few Christmases ago—a magnifier for my iPhone camera. I have to tell you: I LOVE this thing! For diagnositic usefulness during a consult, you cannot beat magnification (Dr. Nicole Rogers even won the poster competition in Alaska with a little device like this)! If you are not already using it for your patients, having a camera like this (or a video microscope) enables instant analysis and feedback for your patient. They will love it and you will, too. Now let’s test your skills for diagnosing some of these commonly seen photomicrographs of the scalp. 1. This patient has been: 4. The following microscopic photo is an example of: A. Shaving his hair recently A. An ingrown hair B. Plucking out his own hair B. Diffuse folliculitis C. Using keratin hair fibers (aka Toppik®, etc.) C. Donor area 6 months post FUE hair surgery D. Getting regular “Brazilian blowouts” D. Follicular plugging 2. This patient shows evidence of: 5. What recently happened to the hairs in this photo? A. Exclamation point hairs indicating trichotillomania A. They were recently backcombed as evidenced by their B. Alopecia areata ruffled cuticle. C. Loss of follicular openings B. They were recently cut as shown by their blunt (i.e., not D. -

(In)Determinable: Race in Brazil and the United States

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 14 2009 Determining the (In)Determinable: Race in Brazil and the United States D. Wendy Greene Cumberland School fo Law at Samford University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Education Law Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation D. W. Greene, Determining the (In)Determinable: Race in Brazil and the United States, 14 MICH. J. RACE & L. 143 (2009). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol14/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DETERMINING THE (IN)DETERMINABLE: RACE IN BRAZIL AND THE UNITED STATES D. Wendy Greene* In recent years, the Brazilian states of Rio de Janeiro, So Paulo, and Mato Grasso du Sol have implemented race-conscious affirmative action programs in higher education. These states established admissions quotas in public universities '' for Afro-Brazilians or afrodescendentes. As a result, determining who is "Black has become a complex yet important undertaking in Brazil. Scholars and the general public alike have claimed that the determination of Blackness in Brazil is different than in the United States; determining Blackness in the United States is allegedly a simpler task than in Brazil. In Brazil it is widely acknowledged that most Brazilians are descendants of Aficans in light of the pervasive miscegenation that occurred during and after the Portuguese and Brazilian enslavement of * Assistant Professor of Law, Cumberland School of Law at Samford University. -

Hair Removal & Skin Rejuvenation Machine

Hair Removal & Skin Rejuvenation Machine IPL Hair Removal IPL laser hair removal is a very popular method of hair removal. An IPL laser uses “intense pulsed light” to gently and safely removes hair on the face, legs, back, and bikini/pubic areas. The pulses of light focus their heat on the hair follicles, destroying them without burning or damaging the skin. IPL laser hair removal is quick and veritably painless. Side effects are few, but may include redness or swelling of the treated area; this should disappear rapidly. Good candidates for IPL laser hair removal will have lighter skin and darker hair, since IPL targets pigment in the hair follicles. Many people have experienced permanent hair removal with this method; if hair does grow back, it is often sparse and finer in texture. Laser Hair removal. Laser hair removal is a gentle and effective way to permanently reduce unwanted hair from virtually any area of the body. Locate a laser hair removal clinic in your area and acquire information on the latest laser hair removal options for men and women by reading the sections below. Laser Hair Removal Procedure Laser hair removal is most effective when hair is in the growth stage. Because hair grows in cycles, laser hair removal patients typically require a series of four to six sessions spaced approximately one month apart for maximum results. www.globalclinic.co During Laser Hair Removal Treatment Typically, the areas to be treated are shaved a few days prior to the laser hair removal treatment. On the day of the procedure, an anesthetic cream may be applied, although this step is not necessary. -

Puberty Changes in Boys

PUBERTY CHANGES IN BOYS The changes of puberty in boys include growth of testes, growth of the penis, growth of pubic hair, voice change, and height spurt. An individual boy may begin his changes at a time different from his peers. TESTES DEVELOPMENT Growth of testes is usually the first change for boys. The scrotum lengthens and becomes a darker color. These changes begin between 9 ½ and 13 ½ years of age. PENIS DEVELOPMENT Growth of the penis occurs between ages 10 and 14. PUBIC HAIR Pubic hair and underarm hair appear between the ages of 10 and 14. At first the hair is fine and thin but becomes curly and coarse over time. GROWTH SPURT Increased height and change in body shape with broadening shoulders begin between the ages of 11 and 16. The voice also deepens. During this time, a boy may notice some temporary breast enlargement. This is completely normal, very common, and is no cause for concern. It will disappear with time. FACIAL AND CHEST HAIR Facial and chest hair appear at around age 17. The thickness of the beard is quite variable and depends on genes. Some men have little or no chest hair and very light beards, while others have dense growth. The amount of hair is unrelated to masculinity. ERECTIONS / EJACULATIONS Erections occur more often during puberty; sometimes a boy will have an erection for no apparent reason – this is common and normal. Ejaculation, the release of semen from the penis, begins during puberty. Like erections, ejaculation can occur for no obvious reason, especially during sleep. -

Does Materialism Predict Body Hair Removal Among Undergraduate Males and Females? Brianna Ballew Grand Valley State University, [email protected]

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Honors Projects Undergraduate Research and Creative Practice 4-2016 Does Materialism Predict Body Hair Removal Among Undergraduate Males and Females? Brianna Ballew Grand Valley State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Ballew, Brianna, "Does Materialism Predict Body Hair Removal Among Undergraduate Males and Females?" (2016). Honors Projects. 576. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/honorsprojects/576 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research and Creative Practice at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Materialist Values and Body Hair Removal 1 Running head: Materialist Values and Body Hair Removal Does Materialism Predict Body Hair Removal Among Undergraduate Males and Females? Brianna Ballew Grand Valley State University Faculty Advisor: Donna Henderson-King Ph.D. – Psychology Department 499 Honors Senior Project April, 2016 Materialist Values and Body Hair Removal 2 Abstract Previous research indicates that materialistic women are more likely to want to alter their bodies (Henderson-King & Brooks, 2009). This study focuses specifically on the relationship between materialism and body hair removal. We collected information about the frequency of body hair removal, reasons for hair removal, and materialism (Richins & Dawson, 1992). Findings indicate that males and females do not significantly differ on materialist values. Correlational analyses reveal that for women, materialism is related to frequency of hair removal for several body sites; for men, however, materialism was related to body hair removal for only a single site. -

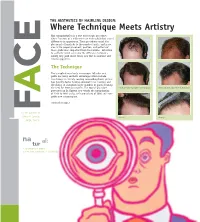

Where Technique Meets Artistry Hair Transplantation Is a True Microscopic Procedure, Where Fractions of a Millimeter Can Make Subtle but Critical

THE AESTHETICS OF HAIRLINE DESIGN: Where Technique Meets Artistry Hair transplantation is a true microscopic procedure, where fractions of a millimeter can make subtle but critical E differences in appearance. These procedures entail the placement of hundreds to thousands of grafts, and in no area is the proper placement, position, and pattern of these grafts more important than the hairline. Attention to aesthetic detail can make the difference between a merely very good result versus one that is excellent and natural appearing. C The Technique The transplanting of only microscopic follicular unit grafts has many aesthetic advantages which include: less damage to already existing surrounding hairs; greater hair density; faster healing; minimal to no scarring; and the ability to transplant larger numbers of grafts meaning the need for fewer procedures. The typical procedure Before and after a procedure of 2400 grafts Before and after a procedure of 2500 grafts performed by Dr. Epstein now entails the transplanting A of 2200 to 2400 grafts, with procedures of 3000 and more grafts now commonplace. continued on page 2 F For the patients of Jeffrey S. Epstein, Close-up Close-up M. D., F.A .C.S. na al: tur 1. As existing in nature 2. Free from pretension or artificiality WORDS FROM THE DOCTOR THE AESTHETICS OF HAIRLINE DESIGN (cont.) Since 1993, I have been fortunate to participate in the evolution The Aesthetics of the specialties of surgical hair The transplanted hairlines on this page all restoration and facial plastic demonstrate different aesthetic aspects of a natural a surgery. Few other surgical appearing hairline. -

The Relationship of Psychological Trauma with Trichotillomania and Skin Picking

Journal name: Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment Article Designation: Original Research Year: 2015 Volume: 11 Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment Dovepress Running head verso: Özten et al Running head recto: Psychological trauma with trichotillomania and skin picking open access to scientific and medical research DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S79554 Open Access Full Text Article ORIGINAL RESEARCH The relationship of psychological trauma with trichotillomania and skin picking Eylem Özten1 Objective: Interactions between psychological, biological and environmental factors are Gökben Hızlı Sayar1 important in development of trichotillomania and skin picking. The aim of this study is to Gül Eryılmaz1 determine the relationship of traumatic life events, symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder Gaye Kag˘an2 and dissociation in patients with diagnoses of trichotillomania and skin picking disorder. Sibel Işık3 Methods: The study included patients who was diagnosed with trichotillomania (n=23) or skin Og˘uz Karamustafalıog˘lu4 picking disorder (n=44), and healthy controls (n=37). Beck Depression Inventory, Traumatic Stress Symptoms Scale and Dissociative Experiences Scale were administered. All groups 1 Neuropsychiatry Health, Practice, checked a list of traumatic life events to determine the exposed traumatic events. and Research Center, Üsküdar University, 2Istanbul Neuropsychiatry Results: There was no statistical significance between three groups in terms of Dissociative Hospital, Üsküdar University, 3Turkish Experiences Scale -

Body Depilation Among Women and Men: the Association of Body Hair Reduction Or Removal with Body Satisfaction, Appearance Compar

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2012 Body Depilation among Women and Men: The Association of Body Hair Reduction or Removal with Body Satisfaction, Appearance Comparison, Body Image Disturbance, and Body Dysmorphic Disorder Symptomatology Michael Scott Boroughs University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Clinical Psychology Commons, and the Sociology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Boroughs, Michael Scott, "Body Depilation among Women and Men: The Association of Body Hair Reduction or Removal with Body Satisfaction, Appearance Comparison, Body Image Disturbance, and Body Dysmorphic Disorder Symptomatology" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3985 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Body Depilation among Women and Men: The Association of Body Hair Reduction or Removal with Body Satisfaction, Appearance Comparison, Body Image Disturbance, and Body Dysmorphic Disorder Symptomatology by Michael S. Boroughs A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Psychology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: J. Kevin Thompson, Ph.D. Vicky Phares, Ph.D. Cynthia R. Cimino, Ph.D. Joseph A. Vandello, Ph.D. Brent J. Small, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 12, 2010 Keywords: body image, body hair, human appearance, attractiveness, Social Comparison Theory, muscularity, masculinity, femininity Copyright © 2012, Michael S. -

Inheritance of Hypertrichosis Pinnae Auris-A Review of Literature Anatomy Section

DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2018/30757.11295 Review Article Inheritance of Hypertrichosis Pinnae Auris-A Review of Literature Anatomy Section NEHA BARYAH1, KEWAL KRISHAN2, SANJEEV PURI3, TANUJ KANCHAN4 ABSTRACT Hypertrichosis is an excessive growth of hair on a particular area of the body which is abnormal for the age, sex or race of an individual. The presence of the excessive coarse black hair on the auricle of the human ear is referred to as hypertrichosis pinnae auris or hairy ears. The condition is primarily restricted to older men and occasionally observed in females. According to the available literature, hypertrichosis pinnae auris is a Y-linked character. A number of studies have shown that the inheritance of the trait is from father to the son, any exceptions can be attributed to the lack of penetrance of the gene or crossing over from Y to X chromosome. A few researchers have suggested the probability of it being inherited in an autosomal manner. The mode of inheritance of the trait thus, remains controversial as to whether it is Y-linked or autosomal or perhaps both. The present article reviews various available studies on hypertrichosis pinnae auris in different populations of the world. It further deliberates on different aspects of the modes of inheritance of hypertrichosis pinnae auris and discusses the contradictions in its inheritance. The understanding of this area of research is significant for studying morphological variations and their genetic basis, sex differences among individuals and populations together with intergroup differences involving anthropology, anatomy, comparative morphology, personal identification and human genetics. Keywords: Biological anthropology, Hairy ears, Human biology, Human genetics, Pedigree analysis, Penetrance, Population variation, Y-linkage INTRODUCTION hairs) hairs on different areas of the pinna [6]. -

The Relationship of Psychological Trauma with Trichotillomania and Skin Picking

Journal name: Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment Article Designation: Original Research Year: 2015 Volume: 11 Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment Dovepress Running head verso: Özten et al Running head recto: Psychological trauma with trichotillomania and skin picking open access to scientific and medical research DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S79554 Open Access Full Text Article ORIGINAL RESEARCH The relationship of psychological trauma with trichotillomania and skin picking Eylem Özten1 Objective: Interactions between psychological, biological and environmental factors are Gökben Hızlı Sayar1 important in development of trichotillomania and skin picking. The aim of this study is to Gül Eryılmaz1 determine the relationship of traumatic life events, symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder Gaye Kag˘an2 and dissociation in patients with diagnoses of trichotillomania and skin picking disorder. Sibel Işık3 Methods: The study included patients who was diagnosed with trichotillomania (n=23) or skin Og˘uz Karamustafalıog˘lu4 picking disorder (n=44), and healthy controls (n=37). Beck Depression Inventory, Traumatic Stress Symptoms Scale and Dissociative Experiences Scale were administered. All groups 1 Neuropsychiatry Health, Practice, checked a list of traumatic life events to determine the exposed traumatic events. and Research Center, Üsküdar University, 2Istanbul Neuropsychiatry Results: There was no statistical significance between three groups in terms of Dissociative Hospital, Üsküdar University, 3Turkish Experiences Scale -

Being in Afro-Brazilian Families by Elizabeth Hordge

Home is Where the Hurt Is: Racial Socialization, Stigma, and Well- Being in Afro-Brazilian Families By Elizabeth Hordge Freeman Department of Sociology Duke University Date: _____________________ Approved: ________________________________________ Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, Co-Supervisor _________________________________________ Linda George, Co-Supervisor _________________________________________ Lynn Smith-Lovin _________________________________________ Linda Burton __________________________________________ Sherman James Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Sociology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 ! ABSTRACT Home is Where the Hurt Is: Racial Socialization, Stigma, and Well- Being in Afro-Brazilian Families By Elizabeth Hordge Freeman Department of Sociology Duke University Date: _____________________ Approved: ________________________________________ Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, Co-Supervisor _________________________________________ Linda George, Co-Supervisor _________________________________________ Lynn Smith-Lovin _________________________________________ Linda Burton __________________________________________ Sherman James An abstract submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Sociology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 ! ! Copyright by Elizabeth Hordge Freeman 2012 ! Abstract This dissertation examines racial socialization in Afro-Brazilian families in -

Circulating and Intraprostatic Sex Steroid Hormonal Profiles in Relation

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Staff U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Publications 2017 Circulating and intraprostatic sex steroid hormonal profiles in relation to male pattern baldness and chest hair density among men diagnosed with localized prostate cancers Cindy Ke Zhou National Cancer Institute, [email protected] Frank Z. Stanczyk University of Southern California, Los Angeles Muhannad Hafi George Washington University Carmela C. Veneroso George Washington University Barlow Lynch Doctors Community Hospital See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/veterans Zhou, Cindy Ke; Stanczyk, Frank Z.; Hafi, Muhannad; Veneroso, Carmela C.; Lynch, Barlow; Falk, Roni T.; Niwa, Shelley; Emanuel, Eric; Gao, Yu-Tang; Hemstreet, George P.; Zolfghari, Ladan; Carroll, Peter R.; Manyak, Michael J.; Sesterhenn, Isabell A.; Levine, Paul H.; Hsing, Ann W.; and Cook, Michael B., "Circulating and intraprostatic sex steroid hormonal profiles in relation to male pattern baldness and chest hair density among men diagnosed with localized prostate cancers" (2017). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Staff Publications. 120. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/veterans/120 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Staff ubP lications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Cindy Ke Zhou, Frank Z. Stanczyk, Muhannad Hafi, Carmela C. Veneroso, Barlow Lynch, Roni T. Falk, Shelley Niwa, Eric Emanuel, Yu-Tang Gao, George P.