Franz Kafka, Before The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kafka Protagonist As Knight Errant and Scapegoat

tJBIa7I vAl, O7/ THE KAFKA PROTAGONIST AS KNIGHT ERRANT AND SCAPEGOAT THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Mary R. Scrogin, B. A. Denton, Texas August, 1975 10 Scrogin, Mary R., The Kafka Protagonist as night Errant and Scapegoat. Master of Arts (English), August, 1975, 136 pp., bibliography, 34 titles. This study presents an alternative approach to the novels of Franz Kafka through demonstrating that the Kafkan protagonist may be conceptualized in terms of mythic arche- types: the knight errant and the pharmakos. These complementary yet contending personalities animate the Kafkan victim-hero and account for his paradoxical nature. The widely varying fates of Karl Rossmann, Joseph K., and K. are foreshadowed and partially explained by their simultaneous kinship and uniqueness. The Kafka protagonist, like the hero of quest- romance, is engaged in a quest which symbolizes man's yearning to transcend sterile human existence. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION . .......... 1 II. THE SPARED SACRIFICE...-.-.................... 16 III. THE FAILED QUEST... .......... 49 IV. THE REDEMPTIVE QUEST........... .......... 91 BIBLIOGRAPHY.. --...........-.......-.-.-.-.-....... 134 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Speaking of the allegorical nature of much contemporary American fiction, Raymond Olderman states in Beyond the Waste Land that it "primarily reinforces the sense that contemporary fact is fabulous and may easily refer to meanings but never to any one simple Meaning." 1 A paraphrase of Olderman's comment may be appropriately applied to the writing of Franz Kafka: a Kafkan fable may easily refer to meanings but never to any one Meaning. -

Featuring Martin Kippenberger's the Happy

FONDAZIONE PRADA PRESENTS THE EXHIBITION “K” FEATURING MARTIN KIPPENBERGER’S THE HAPPY END OF FRANZ KAFKA’S ‘AMERIKA’ ACCOMPANIED BY ORSON WELLES’ FILM THE TRIAL AND TANGERINE DREAM’S ALBUM THE CASTLE, IN MILAN FROM 21 FEBRUARY TO 27 JULY 2020 Milan, 31 January 2020 – Fondazione Prada presents the exhibition “K” in its Milan venue from 21 February to 27 July 2020 (press preview on Wednesday 19 February). This project, featuring Martin Kippenberger’s legendary artworkThe Happy End of Franz Kafka’s “Amerika” accompanied by Orson Welles’ iconic film The Trial and Tangerine Dream’s late electronic album The Castle, is conceived by Udo Kittelmann as a coexisting trilogy. “K” is inspired by three uncompleted and seminal novels by Franz Kafka (1883-1924) ¾Amerika (America), Der Prozess (The Trial), and Das Schloss (The Castle)¾ posthumously published from 1925 to 1927. The unfinished nature of these books allows multiple and open readings and their adaptation into an exhibition project by visual artist Martin Kippenberger, film director Orson Welles, and electronic music band Tangerine Dream, who explored the novels’ subjects and atmospheres through allusions and interpretations. Visitors will be invited to experience three possible creative encounters with Kafka’s oeuvre through a simultaneous presentation of art, cinema and music works, respectively in the Podium, Cinema and Cisterna.“K” proves Fondazione Prada’s intention to cross the boundaries of contemporary art and embrace a vaste cultural sphere, that also comprises historical perspectives and interests in other languages, such as cinema, music, literature and their possible interconnections and exchanges. As underlined by Udo Kittelmann, “America, The Trial, and The Castle form a ‘trilogy of loneliness,’ according to Kafka’s executor Max Brod. -

EXISTENTIAL CRISIS in FRANZ Kl~Fkl:T

EXISTENTIAL CRISIS IN FRANZ Kl~FKl:t. Thesis submitted to the University ofNor~b ~'!e:n~al for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Ph.Ho§'Ophy. By Miss Rosy Chamling Department of English University of North Bengal Dist. Darjeeling-7340 13 West Bengal 2010 gt)l.IN'tO rroit<. I • NlVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL P.O. NORTH BENGAL UNIVERSITY, HEAD Raja Rammohunpur, Dist. Da~eeling, DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH West Bengal, India, PIN- 734013. Phone: (0353) 2776 350 Ref No .................................................... Dated .....?.J..~ ..9 . .7.: ... ............. 20. /.~. TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN This is to certify that Miss Rosy Cham!ing has completed her Research Work on •• Existential Crisis in Franz Kafka". As the thesis bears the marks of originality and analytic thinking, I recommend its submission for evaluation . \i~?~] j' {'f- f ~ . I) t' ( r . ~ . s amanta .) u, o:;.?o"" Supervis~r & Head Dept. of English, NBU .. Contents Page No. Preface ......................................................................................... 1-vn Acknowledgements ...................................................................... viii L1st. ot~A'b o -rev1at1ons . ................................................................... 1x. Chapter- I Introduction................................................... 1 1 Chapter- II The Critical Scene ......................................... 32-52 Chapter- HI Authority and the Individual. ........................ 53-110 Chapter- IV Tragic Humanism in Kafka........................... 111-17 5 Chapter- V Realism -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

51.Dr.Ajoy-Batta-Article.Pdf

www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 UGC-Approved Journal An International Refereed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 2.24 (IIJIF) Franz Kafka and Existentialism Dr. Ajoy Batta Associate Professor and Head Department of English, School of Arts and Languages Lovely Professional University, Phagwara (Punjab) Abstract: Franz Kafka was born on July 3, 1883 at Prague. His posthumous works brought him fame not only in Germany, but in Europe as well. By 1946 Kafka‟s works had a great effect abroad, and especially in translation. Apart from Max Brod who was the first commentator and publisher of the first Franz Kafka biography, we have Edwin and Willa Muir, principle English translators of Kafka‟s works. Majority studies of Franz Kafka‟s fictions generally present his works as an engagement with absurdity, a criticism of society, element of metaphysical, or the resultant of his legal profession, in the course failing to record the European influences that form an important factor of his fictions. In order to achieve a newer perspective in Kafka‟s art, and to understand his fictions in a better way, the present paper endeavors to trace the European influences particularly the influences existentialists like Kierkegaard, Dostoevsky and Nietzsche in the fictions of Kafka. Keywords: Existentialism, absurd, meaningless, superman, despair, identity. Research Paper: Friedrich Nietzsche is perhaps the most conspicuous figure among the catalysts of existentialism. He is often regarded as one of the first, and most influential modern existential philosopher. His thoughts extended a deep influence during the 20th century, especially in Europe. With him existentialism became a direct revolt against the state, orthodox religion and philosophical systems. -

Franz Kafka, the Trial

oxford world’s classics THE TRIAL Mike Mitchell taught at the universities of Reading and Stirling before becoming a full-time literary translator. He is the co-author of Harrap’s German Grammar and the translator of numerous works of German fiction, for which he has been eight times shortlisted for prizes; his translation of Herbert Rosendorfer’s Letters Back to Ancient China won the Schlegel – Tieck Prize in 1998. His translation of Georges Rodenbach’s The Bells of Bruges was published in 2007. Ritchie Robertson is Fellow and Tutor in German at St John’s College, Oxford. He is the author of Kafka: A Very Short Introduction (2004) and editor of The Cambridge Companion to Thomas Mann (2002). For Oxford World’s Classics he has translated Hoffmann’s The Golden Pot and Other Stories and introduced editions of Freud and Schnitzler. oxford world’s classics For over 100 years Oxford World’s Classics have brought readers closer to the world’s great literature. Now with over 700 titles—from the 4,000-year-old myths of Mesopotamia to the twentieth century’s greatest novels—the series makes available lesser-known as well as celebrated writing. The pocket-sized hardbacks of the early years contained introductions by Virginia Woolf, T. S. Eliot, Graham Greene, and other literary figures which enriched the experience of reading. Today the series is recognized for its fine scholarship and reliability in texts that span world literature, drama and poetry, religion, philosophy, and politics. Each edition includes perceptive commentary and essential background information to meet the changing needs of readers. -

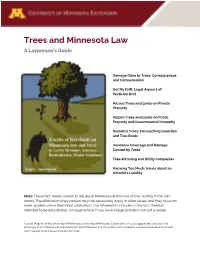

Trees and Minnesota

Trees and Minnesota Law A Layperson’s Guide Damage Done to Trees: Consequences and Compensation Get My Drift: Legal Aspects of Pesticide Drift Hazard Trees and Limbs on Private Property Hazard Trees and Limbs on Public Property and Governmental Immunity Nuisance Trees: Encroaching Branches and Tree Roots Insurance Coverage and Damage Caused by Trees Tree-trimming and Utility Companies Knowing Too Much: Issues about an Arborist’s Liability Note: These fact sheets pertain to the law in Minnesota at the time of their writing in the mid 2000s. The information they contain may not necessarily apply in other states, and they have not been updated since their initial publication. The information included in the fact sheets is intended to be educational, not legal advice. If you have a legal problem, consult a lawyer. © 2008, Regents of the University of Minnesota. University of Minnesota Extension is an equal opportunity educator and employer. In accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, this publication/material is available in alternative formats upon request. Direct requests to 612-624-1222. Damage Done to Trees: Consequences and Compensation My neighbor cut down trees on my property. What are my legal rights? Cutting down a tree on another’s property without permission is trespass and carries a stiff penalty. A Minnesota statute provides that whoever intentionally cuts down a tree without the tree owner’s permission can be assessed three times (“treble”) the amount of monetary loss suffered by the tree owner.1 If the tree damage is unintentional, then the tree owner’s loss would not be tripled. -

J-S50031-20 *Retired Senior Judge Assigned to the Superior Court

J-S50031-20 NON-PRECEDENTIAL DECISION – SEE SUPERIOR COURT I.O.P. 65.37 COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, : IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF : PENNSYLVANIA Appellee : : v. : : KENNETH HOYLE, : : Appellant : No. 1362 EDA 2020 Appeal from the Judgment of Sentence Entered October 19, 2018 in the Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia County Criminal Division at No(s): CP-51-CR-0008019-2017 COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, : IN THE SUPERIOR COURT OF : PENNSYLVANIA Appellee : : v. : : KENNETH HOYLE, : : Appellant : No. 1363 EDA 2020 Appeal from the Judgment of Sentence Entered October 19, 2018 in the Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia County Criminal Division at No(s): CP-51-CR-0008020-2017 BEFORE: BENDER, P.J.E., SHOGAN, J. and STRASSBURGER, J.* MEMORANDUM BY BENDER, P.J.E.: FILED APRIL 20, 2021 Kenneth Hoyle (Appellant) appeals nunc pro tunc from the October 19, 2018 judgments of sentence of two consecutive terms of life incarceration, without the possibility of parole, imposed after a jury convicted him of two counts of first-degree murder and one count of possessing an instrument of crime (PIC). Upon review, we affirm. *Retired Senior Judge assigned to the Superior Court. J-S50031-20 Appellant’s charges stem from an incident “in the early morning hours of July 16, 2017, [when] Appellant shot his [next-door] neighbor, Robert DePaul, and DePaul’s female companion, August Dempsey, after a verbal altercation.” Commonwealth v. Hoyle, No. 443 EDA 2019, unpublished memorandum at 1 (Pa. Super. filed March 27, 2020). The trial court thoroughly recounted the evidence presented at trial, as follows. Police officer Brian Brent testified that he was at 4670 James Street for a separate incident when he heard a man’s voice yelling followed by a few gunshots from somewhere in the area. -

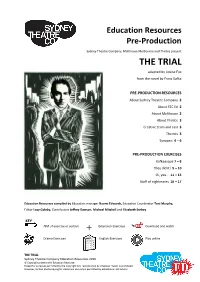

THE TRIAL Adapted by Louise Fox from the Novel by Franz Kafka

Education Resources Pre‐Production Sydney Theatre Company, Malthouse Melbourne and ThinIce present THE TRIAL adapted by Louise Fox from the novel by Franz Kafka PRE‐PRODUCTION RESOURCES About Sydney Theatre Company 2 About STC Ed 2 About Malthouse 2 About ThinIce 3 Creative team and cast 3 Themes 3 Synopsis 4 – 6 PRE‐PRODUCTION EXERCISES Kafkaesque 7 – 8 They did it! 9 – 10 Oi, you… 11 – 15 Stuff of nightmares 16 – 17 Education Resources compiled by Education manager Naomi Edwards, Education Coordinator Toni Murphy, Editor Lucy Goleby, Contributors Jeffrey Dawson, Michael Mitchell and Elizabeth Surbey KEY AIM of exercise or section Extension Exercises Download and watch + Drama Exercises English Exercises Play online THE TRIAL Sydney Theatre Company Education Resources 2010 © Copyright protects this Education Resource. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited. However, limited photocopying for classroom use only is permitted by educational institutions. PRE‐PRODUCTION RESOURCES ABOUT SYDNEY THEATRE COMPANY www.sydneytheatre.com.au/about ABOUT STCED www.sydneytheatre.com.au/stced/about ABOUT MALTHOUSE www.malthousetheatre.com.au/page/OUR_COMPANY Malthouse Theatre engages with Australia’s cultural and imaginative life. Malthouse Theatre produces and presents Australian contemporary theatre, a broadly defined program of work conceived and created in collaboration with writers, directors, designers, choreographers, audio artists and performers – a contemporary theatre where the combined possibilities of all the theatre arts are offered centre stage. Alive to the changing dynamics of a theatre in contest with contemporary life and the contemporary imagination, we undertake this challenge as an offering to the past, a witnessing of the present and as a manifestation of our hopes and fears for the future. -

Little Women, Or, Meg, Jo, Beth And

i; UNIVERSITY OF N.C. AT CHAPEL HILL llllllllili 00022092959 This BOOK may be kept out TWO WEEKS ONLY, and is subject to a fine of FIVE CENTS a day thereafter. It was taken out on the day indicated below: T^^-p,^ / ^-. V /^ ^/ .^..^•/'^^ ; / '-' itjL f They all drew to the tire, mother in the hi^r chair, with Beth at her feet; Meg and Amy perched on either arm of the chair, and Jo leaning on the back. — Page 12. LITTLE WOMEN MEG, JO, BETH AND AMY BY LOUISA M. ALCOTT ILLUSTRATED BY MAY ALCOTT BOSTON ROBERTS BROTHERS 1S69 Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1868, by LOUISA M. ALCOTT, In the Clerk's office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts. Stebeotyped bt Innes & Regas, 55 Water Street, Boston. Presswork by John Wilson and Son. .-^t^^ cS, i^ '^^ZuCl-^^ Digitized by tine Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill http://www.archive.org/details/littlewonienormeg01alco CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. PAGE Playing Pilgrims 7 CHAPTER II. A Merry Christmas . ' ^3 CHAPTER III. The Laurence Boy 39 CHAPTER IV. Burdens 54 CHAPTER V. Being Neighborly 71 CHAPTER VI. Beth finds the Palace Beautiful 88 CHAPTER VII. Amy's Valley of Humiliation 98 CHAPTER VIII. Jo meets Apollyon 108 CHAPTER IX. Meg goes to Vanity Fair 124 CHAPTER X. P. The C. and P. O. , 147 CHAPTER XI. Experiments 158 iv Contents. CHAPTER XII. PAGE Camp Laurence ... 174 CHAPTER XIII. Castles in the Air * 202 CHAPTER XIV. Secrets ai6 CHAPTER XV. -

Franz Kafka's

Kafka and the Universal Interdisciplinary German Cultural Studies Edited by Irene Kacandes Volume 21 Kafka and the Universal Edited by Arthur Cools and Vivian Liska An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-045532-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-045811-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-045743-8 ISSN 1861-8030 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2016 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image: Franz Kafka, 1917. © akg-images / Archiv K. Wagenbach Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Table of Contents Arthur Cools and Vivian Liska Kafka and the Universal: Introduction 1 Section 1: The Ambiguity of the Singular Stanley Corngold The Singular Accident in a Universe of Risk: An Approach to Kafka and the Paradox of the Universal 13 Brendan Moran Philosophy and Ambiguity in Benjamin’s Kafka 43 Søren Rosendal The Logic of the “Swamp World”: Hegel with Kafka on the Contradiction of Freedom 66 Arnaud Villani The Necessary Revision of the Concept of the Universal: Kafka’s “Singularity” 90 Section 2: Before the Law Eli Schonfeld Am-ha’aretz: The Law of the Singular. -

K. Stays in the Picture: Filming the Novels of Franz Kafka

K. Stays in the Picture: Filming the Novels of Franz Kafka A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of German Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences by Matthew R. Bauman B.A. The Ohio State University May 2012 Committee Chair: Harold Herzog, Ph.D. Abstract From the man who wakes up one morning transformed into a bug, to the man arrested in his bedroom by a shadowy, extra-legal police force despite, seemingly, having done nothing wrong, the author Franz Kafka has put his protagonists into some of the most identifiable and bizarre predicaments of twentieth century literature. It is no surprise then that many notable directors have undertaken the challenge of translating the tales of these protagonists onto film. Themselves possessed of inspired and unique minds themselves, it should also come as no surprise that these filmmakers each take a distinctly individual approach to the source material, often with an agenda markedly different from Kafka’s own, and, by extension, produce final products that differ greatly both from each other and from the source material. The goal of this thesis is to provide case studies of three such adaptations of Franz Kafka’s work: Orson Welles’s The Trial (1962), adapted from the novel Der Prozeß; Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub’s Klassenverhältnisse (1984), adapted from the incomplete novel Der Verschollene; and Michael Haneke’s Das Schloß (1997), adapted from the novel of the same name.