The Judicial Reforms of 1937

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President Roosevelt and the Supreme Court Bill of 1937

President Roosevelt and the Supreme Court bill of 1937 Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Hoffman, Ralph Nicholas, 1930- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 09:02:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/319079 PRESIDENT ROOSEVELT AND THE SUPREME COURT BILL OF 1937 by Ralph Nicholas Hoffman, Jr. A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of History and Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Graduate College, University of Arizona 1954 This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the Library to be made avail able to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without spec ial permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the dean of the Graduate College when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other in stances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: TABLE.' OF.GOWTENTS Chapter / . Page Ic PHEYIOUS CHALLENGES TO THE JODlClMXo , V . -

The Instrumental Role of Congressman Hatton Sumners in the Resolution of the 1937 Court-Packing Crisis, 54 UIC J

UIC Law Review Volume 54 Issue 2 Article 1 2021 “What I Said Was ‘Here Is Where I Cash In’”: the Instrumental Role of Congressman Hatton Sumners in the Resolution of the 1937 Court-Packing Crisis, 54 UIC J. Marshall L. Rev. 379 (2021) Josiah Daniel III Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Josiah M. Daniel III, “What I Said Was ‘Here Is Where I Cash In’”: the Instrumental Role of Congressman Hatton Sumners in the Resolution of the 1937 Court-Packing Crisis, 54 UIC J. Marshall L. Rev. 379 (2021) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol54/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “WHAT I SAID WAS ‘HERE IS WHERE I CASH IN’”: THE INSTRUMENTAL ROLE OF CONGRESSMAN HATTON SUMNERS IN THE RESOLUTION OF THE 1937 COURT- PACKING CRISIS JOSIAH M. DANIEL, III* I. THE CONGRESSMAN’S “CASH IN” UTTERANCE UPON DEPARTING THE WHITE HOUSE ON FEBRUARY 5, 1937 ... 379 II. HATTON W. SUMNERS’S LIFE AND CONGRESSIONAL CAREER ......................................................................................... 384 III. THE NEW DEAL’S LITIGATION PROBLEM AND PRESIDENT FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT’S PROPOSED COURT-PACKING SOLUTION ........................................................................ 393 IV. SUMNERS’S TWO JUDICIAL BILLS AS BOOKENDS TO THE CRISIS .............................................................................. 401 a. March 1, 1937: The Retirement Act ....................... 401 b. August 24, 1937: The Intervention Act ................. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFO RM A TIO N TO U SER S This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI film s the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be fromany type of con^uter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependentquality upon o fthe the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and inqjroper alignment can adverse^ afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note wiD indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one e3q)osure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photogr^hs included inoriginal the manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for aiy photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI direct^ to order. UMJ A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313.'761-4700 800/521-0600 LAWLESSNESS AND THE NEW DEAL; CONGRESS AND ANTILYNCHING LEGISLATION, 1934-1938 DISSERTATION presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Robin Bernice Balthrope, A.B., J.D., M.A. -

Elections Have Consequences

LIBERTYVOLUME 10 | ISSUE 1 | March 2021 WATCHPOLITICS.LIVE. BUSINESS. THINK. BELIBERTY. FREE. ELECTIONS HAVE CONSEQUENCES BETTER DAYS AHEAD George Harris CENSORSHIP & THE CANCEL CULTURE Joe Morabito JUST SAY “NO” TO HARRY REID AIRPORT Chuck Muth REPORT: SISOLAK’S EMERGENCY POWERS LACK LEGAL AUTHORITY Deanna Forbush DEMOCRATS WANT A 'RETURN TO CIVILITY'; WHEN DID THEY PRACTICE IT? Larry Elder THE LEFT WANTS UNCONDITIONAL SURRENDER, NOT UNITY Stephen Moore THE WORLD’S LARGEST CANNABIS SUPERSTORE COMPLEX INCLUDES RESTAURANT + MORE! Keep out of reach of children. For use only by adults 21 years of age and older. LIBERTY WATCH Magazine The Gold Standard of Conservatism. Serving Nevada for 15 years, protecting Liberty for a lifetime. LIBERTYWATCHMagazine.com PUBLISHER George E. Harris [email protected] EDITOR content Novell Richards 8 JUST THE FACTS George Harris ASSOCIATE EDITORS BETTER DAYS AHEAD Doug French [email protected] 10 FEATURE Joe Morabito Mark Warden CENSORSHIP & THE CANCEL CULTURE [email protected] 11 MILLENNIALS Ben Shapiro CARTOONIST GET READY FOR 4 YEARS Gary Varvel OF MEDIA SYCOPHANCY OFFICE MANAGER 12 MONEY MATTERS Doug French Franchesca Sanchez SILVER SQUEEZE: DESIGNERS IS THAT ALL THERE IS? Willee Wied Alejandro Sanchez 14 MUTH'S TRUTHS Chuck Muth JUST SAY “NO” TO HARRY REID AIRPORT CONTRIBUTING WRITERS John Fund 18 COVER Doug French ELECTIONS HAVE CONSEQUENCES Thomas Mitchell Robert Fellner 24 COUNTERPUNCH Victor Davis Hanson Nicole Maroe Judge Andrew P. Napolitano 26 LEGAL BRIEF Deanna Forbush Ben -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

The Mccarran Internal Security Act, 1950-2005: Civil Liberties Versus National Security

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2006 The cM Carran Internal Security Act, 1950-2005: civil liberties versus national security Marc Patenaude Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Patenaude, Marc, "The cM Carran Internal Security Act, 1950-2005: civil liberties versus national security" (2006). LSU Master's Theses. 426. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/426 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MCCARRAN INTERNAL SECURITY ACT, 1950-2005: CIVIL LIBERTIES VERSUS NATIONAL SECURITY A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In The Department of History by Marc Patenaude B.A., University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2003 May 2006 Table of Contents ABSTRACT . iii CHAPTER 1 HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS OF ANTI-COMMUNISM. .1 2 THE MCCARRAN INTERNAL SECURITY ACT OF 1950 . .24 3 THE COURTS LIMIT THE MCCARRAN ACT. .55 4 SEPTEMBER 11, 2001, AND THE FUTURE OF INTERNAL SECURITY . 69 BIBLIOGRAPHY . .. .81 VITA . .86 ii Abstract In response to increased tensions over the Cold War and internal security, and in response to increased anti-Communism during the Red Scare, Congress, in 1950, enacted a notorious piece of legislation. -

Academic Mccarthyism and New York University, 1952–53 10 Phillip Deery

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE FCWH 453233—25/2/2010—RANANDAN—361855 provided by Victoria University Eprints Repository Cold War History Vol. 00, No. 0, 2010, 1–24 5 ‘Running with the Hounds’: Academic McCarthyism and New York University, 1952–53 10 Phillip Deery 15 This paper is an anatomy of an inquisition. It examines the Cold War persecution of Edwin Berry Burgum, a university professor and literary theorist. Whilst his professional competence was consistently applauded, his academic career was abruptly destroyed. His ‘fitness to teach’ was determined by his political beliefs: he was a member of the American Communist Party. The paper 20 argues that New York University, an institution that embodied liberal values, collaborated with McCarthyism. Using previously overlooked or unavailable sources, it reveals cooperation between NYU’s executive officers and the FBI, HUAC and the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee. Through its focus on one individual, the paper illuminates larger themes of the vulnerability of academic 25 freedom and the bureaucratic processes of political repression. At one o’clock on the afternoon of 13 October 1952, a telegram was delivered to Edwin Berry Burgum, literary critic, Associate Professor of English at New York University 30 (NYU), and founding editor of Science & Society. It permanently wrecked his life. The instructions given to Western Union were to ‘Drop If Not Home’, but Burgum was home, at his Upper West Side Manhattan apartment, on that fateful day. The telegram was from his Chancellor, Henry T. Heald, and it read: 35 I regard membership in the Communist Party as disqualifying a teacher for employment at New York University .. -

Congressional Record-Senate

1940 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE 5721 eration of their resolution with reference to the United States us by Thy power that we give heed only to that which is right Housing Authority program; to the Committee on Banking and, speaking the truth in love, may keep ourselves close to and Currency. the lives of the great body of men, and, sharing alike their 8105. Also, petition of the Los Angeles Industrial Union joys and sorrows, may follow in the steps of Him who made Council, Congress of Industrial Organizations, Los Angeles, this world's ills His own, even Jesus Christ, our Lord. Amen. Calif., petitioning consideration of their resolution with ref THE JOURNAL erence to the Dies committee; to the Committee on Rules. 8106. Also, petition of Branch 79, International Workers On request of Mr. BARKLEY, and by unanimous consent, Order, petitioning consideration of their resolution with the reading of the Journal of the proceedings of the calen reference to the Dies committee; to the Committee on Rules. dar day of TUesday, May 7, 1940, was dispensed with, and 8107. Also, petition of Lake County (Ind.) School Em the Journal was approved. ployees Local 123, Hammond, Ind., petitioning consideration MESSAGES FROM THE PRESIDENT of their resolution with reference to Senate bill 591, United Messages in writing from the President of the United States Housing Authority program; to the Committee on States submitting nominations were communicated to the Banking and Currency. Senate by Mr. Latta, one of his secretaries. 8108. Also, petition of Local 18, United Retail and Whole CALL OF THE ROLL sale Employees of America, Philadelphia, Pa., petitioning consideration of their resolution with reference to the so Mr. -

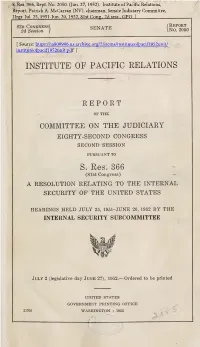

Institute of Pacific Relations. Report

f t I S. Res. 366, Rept. No. 2050. (Jun. 27, 1952). Institute of Pacific Relations, Report, Patrick A. McCarran (NV), chairman, Senate Judiciary Committee, Hrgs. Jul. 25, 1951-Jun. 20, 1952, 81st Cong., 2d sess., GPO. ] s^^^^™ ^^i.?.sri {sraSio [ Source: https://ia800906.us.archive.org/2/items/instituteofpacif1952unit/ instituteofpacif1952unit.pd"a f ] INSTITUTE OF PACIFIC RELATIONS REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY EIGHTY-SECOND CONGRESS SECOND SESSION PURSUANT TO S. Res. 366 (81st Congress) — A RESOLUTION RELATING TO THE INTERNAL SECURITY OF THE UNITED STATES HEARINGS HELD JULY 25, 1951-JUNE 20, 1952 BY THE INTERNAL SECURITY SUBCOMMITTEE July 2 (legislative day June 27), 1952.—Ordered to be printed UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 21705 WASHINGTON : 1952 t? <?-'> -!*TTT .Kb M.!335.4AIS 4 Given By TT Q QTyPT nT7 HP t S^ " *''^-53r,4 I6f / U. S. SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENT AUG 11 1952 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY PAT McCARRAN, Nevada, Chairman HARLEY M. KILGORE, West Virginia ALEXANDER WILEY, Wisconsin JAMES O. EASTLAND, Mississippi WILLIAM LANGER, Nortli Dakota WARREN G. MAGNUSON, Washington HOMER FERGUSON, Michigan HERBERT R. O'CONOR, Maryland WILLIAM E. JENNER, Indiana ESTES KEFAUVER, Tennessee ARTHUR V. WATKINS, Utah WILLIS SMITH, North Carolina ROBERT C. HENDRICKSON, New Jersey J. G. SorRwiNE, Counsel Internal Security Subcommittee PAT McCARRAN, Nevada, Chairman JAMES O. EASTLAND, Mississippi HOMER FERGUSON, Michigan HERBERT R. O'CONOR, Maryland WILLIAM E. JENNER, Indiana WILLIS SMITH, North Carolina ARTHUR V. WATKINS, Utah Robert Morris, Special Counsel Benjamin' Mandel, Director of Research Subcommittee Investigating the Institute of Pacific Relations JAMES O. EASTLAND, Mississippi, Chairman PAT McCARRAN, Nevada HOMER FERGUSON, Michigan II CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 What is IPR? 3 Effect of the Inscitute of Pacific Relations on United States public opinion. -

Congressional Record-Senate Senate

1938 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE 6607 SENATE Mr. AUSTIN. I announce that the Senator from New Hampshire [Mr. BRIDGES] is necessarily absent from the WEDNESDAY, MAY 11, 1938 Senate. <Legislative day of Wednesday, April 20, 1938) The VICE PRESIDENT. Eighty-six Senators have an swered to their names. A quorum is present. The Senate met at 12 o'clock meridian, on the expiration PERSONAL EXPLANATION of the rece5s. THE JOURNAL Mr. McGILL. Mr. President, in this morning's issue of the Washington Herald is an article entitled "Washington . On request of Mr. BARKLEY, and by unanimous consent, the Daily Merry-Go-Round," by Messrs. Drew Pearson and Rob reading of the Journal of the proceedings of the calendar day ert S. Allen, containing a number of statements pertaining Tuesday, May 10, 1938, was dispensed with, and the Journal to what is known as the Spanish embargo. Among them is was approved. a statement relative to myself, and purporting to indicate MESSAGE FROM THE HOUSE a desire upon my part to make certain suggestions to the A message from the House of Representatives, by Mr. Callo President of the United States. way, one of its reading clerks, announced that the House had In order that there may be no niisunderstanding, I take agreed to the report of the committee of. conference on the occasion to read that portion of the article: disagreeing votes of the two Houses on. the amendments of Many Senators caught between two religious fires are worried, the Senate to the bill <H. R. 9218) to establish the composition among them Senator McGILL, of Kansas, a strong Roosevelt sup of the United States Navy, to authorize the construction of porter, who says he will urge the President to lift the em bargo himself without precipitating a Catholic-Protestant feud in certain naval vessels, and for other purposes. -

8634. House of Representatives

' 8634. CONGRESSIO~AL RECORD-HOUSE JUNE 19 Robert T. Sweeney George F. Waters, Jr. · John T. Schneider, Lebanon. Robert Y. Stratton John A. White Fred J. Hepperle, Leola. Robert D. Taplett Elliott Wilson Sylvester C. Eisenman, Marty. Harry W. Taylor John Winterholler Michael P. Garvey, Milbank. Eugene N. Thompson Herbert F. Woodbury Charles P. Corcoran, Miller. Robert J. Trulaske Alexander M. Worth, Jr. Michael F. McGrath, Morristown. Walton L. Turner Richard W. Wyczawsk:i Arthur A. Kluckman, Mound City. Clarence E. Van Ray Howard A. York John Loesch, Oldham. Charles E. Warren Olga R. Otis, Pierpont. POSTMASTERS Harry F. Evers, Pukwana. Harvey J. Seim, Revillo. KENTUCKY Albert H. Fogel, Rosholt. Henry Roe Thompson Kinnaird, Edmonton. Leroy F. Lemert, Spencer. Raymond E. Doyle, Park City. Agnes Parker, Timber Lake. LOUISIANA William A. Bauman, Vermillion. Henry H. Sample, Lecompte. Rose Cole Hoyer, Wagner. NEBRASKA Clarence J. LaBarge, Wakonda. Leo F. Craney, Watertown. James A. Gunn, Ponca. Marion Peterson, Waubay. Robert Harold O'Kane, Wood River. Frank D. Fitch, Wessington. NEVADA Frank B. Kargleder, White Rock. Isaac L. Stone, McGill. Edd A. Sinkler, Wood. Effie M. Perry, Yerington. NORTH CAROLINA John G. Kennedy, Beulaville. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Robert A. Watson, Sr., Jonesboro. WEDNESDAY, JUNE 19, 1940 Parley Potter, Magnolia. The House met at 12 o'clock noon, and was called to order Robert L. Mattocks, Maysville. by the Speaker. Karl M. Cook, Mount Pleasant. The Chaplain, Rev. James Shera Montgomery, D. D., offered Lacy F. Clark, Raeford. the following prayer: James B. Hayes, Rocky Point. Murphy Lee Carr, Rosehill. Almighty God, who dwellest in the beauty and glory of in Lucile L. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. {Th.fi films the text directIy trom the original or copy submitted. Thus, sorne thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type ofcomputer printer. The quality ofthis reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs~ print bleedthrou~ substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMl a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be notOO. AIso, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g.~ maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with smalI overIaps. Each original is aIso photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced fonn at the back ofthe book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reprodueed xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographie prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMl directly to arder. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Raad, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313n61-4700 800/521-0600 The expanding role of the United States Senate in Supreme Court confirmation proceedings Anthony Shane Dolgin Department of History McGill University, ~fontreal April, 1997 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts © Anthony Shane Dolgin, 1997.