Environmental Assessment of the Gaza Strip Following the Escalation of Hostilities in December 2008 – January 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protection of Civilians – Weekly Briefing Notes 22 – 28 February 2006

U N I TOCHA E D Weekly N A Briefing T I O NotesN S 22 – 28 February 2006 N A T I O N S| 1 U N I E S OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS P.O. Box 38712, East Jerusalem, Phone: (+972) 2-582 9962 / 582 5853, Fax: (+972) 2-582 5841 [email protected], www.ochaopt.org Protection of Civilians – Weekly Briefing Notes 22 – 28 February 2006 Of note this period • IDF military operations in Balata camp (Nablus) continued. Four Palestinians including a child were killed and 15 others injured. Two IDF soldiers were also injured in the operation. • A large number of Palestinians injured – including in demonstrations against the construction of the Barrier in Ramallah and Jerusalem and confrontations between the IDF and Palestinian stone throwers in the West Bank. • High number of flying checkpoints observed throughout the West Bank, particularly in Qalqiliya, Nablus and Hebron governorates. 1. Physical Protection Casualties1 80 60 40 20 0 Children Women Injuries Deaths Deaths Deaths Palestinians 71 8 1 - Israelis 10 - - - Internationals ---- • 22 February: IDF soldiers beat and injured a 21-year-old Palestinian in H1 area of Hebron city (Hebron). • 22 February: The IDF injured a 15-year-old Palestinian minor after opening fire towards Palestinian stone throwers in Bani Na’im (Hebron). • 22 February: Palestinians injured one Israeli after opening fire at an Israeli plated vehicle passing on Road 55 near Ázzun (Qalqiliya). • 22 February: The IDF injured one Palestinian man after opening fire at Huwwara checkpoint (Nablus) during unrest at the checkpoint caused by long delays. -

Abuses Against Journalists by Palestinian Security Forces WATCH

Occupied Palestinian Territories HUMAN No News is Good News RIGHTS Abuses against Journalists by Palestinian Security Forces WATCH No News is Good News Abuses against Journalists by Palestinian Security Forces Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-759-0 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org April 2011 ISBN: 1-56432-759-0 No News is Good News Abuses against Journalists by Palestinian Security Forces Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Background ........................................................................................................................ 3 West Bank ....................................................................................................................... 5 Reports of Increased Harassment ............................................................................. 6 The Role of PA Security Forces ................................................................................... 7 Gaza ............................................................................................................................. -

The Origins of Hamas: Militant Legacy Or Israeli Tool?

THE ORIGINS OF HAMAS: MILITANT LEGACY OR ISRAELI TOOL? JEAN-PIERRE FILIU Since its creation in 1987, Hamas has been at the forefront of armed resistance in the occupied Palestinian territories. While the move- ment itself claims an unbroken militancy in Palestine dating back to 1935, others credit post-1967 maneuvers of Israeli Intelligence for its establishment. This article, in assessing these opposing nar- ratives and offering its own interpretation, delves into the historical foundations of Hamas starting with the establishment in 1946 of the Gaza branch of the Muslim Brotherhood (the mother organization) and ending with its emergence as a distinct entity at the outbreak of the !rst intifada. Particular emphasis is given to the Brotherhood’s pre-1987 record of militancy in the Strip, and on the complicated and intertwining relationship between the Brotherhood and Fatah. HAMAS,1 FOUNDED IN the Gaza Strip in December 1987, has been the sub- ject of numerous studies, articles, and analyses,2 particularly since its victory in the Palestinian legislative elections of January 2006 and its takeover of Gaza in June 2007. Yet despite this, little academic atten- tion has been paid to the historical foundations of the movement, which grew out of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Gaza branch established in 1946. Meanwhile, two contradictory interpretations of the movement’s origins are in wide circulation. The !rst portrays Hamas as heir to a militant lineage, rigorously inde- pendent of all Arab regimes, including Egypt, and harking back to ‘Izz al-Din al-Qassam,3 a Syrian cleric killed in 1935 while !ghting the British in Palestine. -

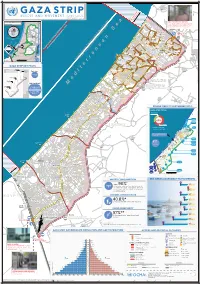

Palestinian Territories MIDDLE EAST UNITARY COUNTRY and WEST ASIA

Palestinian territories MIDDLE EAST UNITARY COUNTRY AND WEST ASIA Basic socio-economic indicators Income group - LOWER MIDDLE INCOME Local currency - Israeli new shekel (ILS) Population and geography Economic data AREA: 6 020 km2 GDP: 19.4 billion (current PPP international dollars) i.e. 4 509 dollars per inhabitant (2014) POPULATION: million inhabitants (2014), an increase 4.295 REAL GDP GROWTH: -1.5% (2014 vs 2013) of 3% per year (2010-2014) UNEMPLOYMENT RATE: 26.9% (2014) 2 DENSITY: 713 inhabitants/km FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT, NET INFLOWS (FDI): 127 (BoP, current USD millions, 2014) URBAN POPULATION: 75.3% of national population GROSS FIXED CAPITAL FORMATION (GFCF): 18.6% of GDP (2014) CAPITAL CITY: Ramallah (2% of national population) HUMAN DEVELOPMENT INDEX: 0.677 (medium), rank 113 Sources: World Bank; UNDP-HDR, ILO Territorial organisation and subnational government RESPONSIBILITIES MUNICIPAL LEVEL INTERMEDIATE LEVEL REGIONAL OR STATE LEVEL TOTAL NUMBER OF SNGs 483 - - 483 Local governments - Municipalities (baladiyeh) Average municipal size: 8 892 inhabitantS Main features of territorial organisation. The Palestinian Authority was born from the Oslo Agreements. Palestine is divided into two main geographical units: the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. It is still an ongoing State construction. The official government of Cisjordania is governed by a President, while the Gaza area is governed by the Hamas. Up to now, most governmental functions are ensured by the State of Israel. In 1994, and upon the establishment of the Palestinian Ministry of Local Government (MoLG), 483 local government units were created, encompassing 103 municipalities and village councils and small clusters. Besides, 16 governorates are also established as deconcentrated level of government. -

Measuring Public Opinion Regarding Peaceful Solution of Palestine Issue

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: F Political Science Volume 14 Issue 4 Version 1.0 Year 2014 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X Measuring Public Opinion Regarding Peaceful Solution of Palestine Issue: An Experimental Study of University Students in Pakistan, Iran and United Arab Emirates By Muhammad Asim Government Postgraduate College Asghar Mall, Pakistan Abstract- This study aimed to measure public opinion in the Pakistan, Iran and United Arab Emirates regarding peaceful solution of Palestine issue Data (N=276) was collected from two universities, one postgraduate college and one degree college in Pakistan, two universities in Iran and two universities in United Arab Emirates. Although, Pakistan and Iran have theocratic environment and we got anti-Israel replies but there were 77 Pakistani and 41 Emirati students who presented their rational views about peaceful solution of this conflict. There is a brief debate on One-State Solution, Two-States Solution, Three-States Solution and the status of Jerusalem. The plan of forming union among the territories of Israel and Palestine, single currency and Rail-Road plan for secular transportation from one region to another is also discussed in this study. During comparing such public opinion with other previous international proposals for resolving this issue, recommendations from the author are presented in the last. Keywords: uae, i-p union, religiosity, eu, state of judea. -

Beneficiary and Community Perspectives on the Palestinian National Cash Transfer Programme

TRANSFORMING COUNTRY BRIEFING CASH TRANSFERS Beneficiary and community perspectives on the Palestinian National Cash Transfer Programme transformingcashtransfers.org Introduction transformingcashtransfers.org Our research aimed to explore the perceptions of cash transfer programme beneficiaries and implementers and other community members, in order to ensure their views are better reflected in policy and programming. Introduction transformingcashtransfers.org There is growing evidence internationally of positive links Key points: between social protection and poverty and vulnerability reduction. However, there has been limited recognition of the • De-developmental policies, recurring social inequalities that perpetuate poverty, such as gender insecurity and dependency on donor inequality, unequal citizenship status and displacement funding are among the key challenges through conflict, and the role social protection can play in in advancing social protection in the tackling these interlinked socio-political vulnerabilities. Occupied Palestinian Territories. • The Palestinian National Cash Transfer This country briefing synthesises qualitative research focusing Programme is an important but on beneficiary and community perceptions of the Palestinian limited component of female-headed National Cash Transfer Programme (PNCTP) in Gaza1 and households’ coping repertoires. West Bank2, as part of a broader research project in five countries (Kenya, Mozambique, OPT, Uganda and Yemen) by • Programme governance requires urgent the Overseas Development -

Gaza Emergency Daily Report – 31 August 2014

Gaza Emergency Daily Report – 31 August 2014 Transport Services Logistics Cluster transportation into the Gaza Strip since activation on 30 July 2014: Total Number of Trucks 184 Total Number of Pallets 4809 Total number Organizations Supported 37 Logistics Cluster transportation into the Gaza Strip – 31 August 2014: Final Number Number of Consignor From Consignee Sector Destination of pallets Trucks Shelter Global Communities Ramallah Gaza City CHF International 30 1 Food Ministry Of Social Ministry Of Social Shelter Ramallah Gaza City 140 5 Affairs (MoSA) Affairs (MoSA) Gaza WASH Agricultural Agricultural Food Development Development Ramallah Gaza City 52 Shelter 2 Association (PARC) Association (PARC) WASH Ramallah Gaza Union of Union of Agricultural Food Agricultural Work Work Committees Nablus Gaza City 31 Shelter 1 Committees (UAWC) WASH (UAWC) Food Hebron Food Trade Ministry Of Social Hebron Gaza City 56 Shelter 2 Association Affairs (MoSA) Gaza WASH Food Social Welfare Ministry Of Social Bethlehem Gaza City 23 Shelter 1 Committee Affairs (MoSA) Gaza WASH Private donation from Ministry Of Social Shelter Bethlehem Gaza City 14 Dar Salah Affairs (MoSA) Gaza Food Earth & Human Applied Research Center for Shelter Institute- Bethlehem Gaza City 2 1 researches and Food Jerusalem(ARIJ) studies (EHCRS) Social Welfare Ministry Of Social Shelter Bethlehem Gaza City 10 Committee Affairs (MoSA) Gaza Food TOTAL 358 13 Coordination/ Information Management/ GIS The Logistics Cluster is compiling information and assessing partners’ needs to determine whether the Rafah crossing can be used on a more permanent basis to support the humanitarian community transport relief items from Egypt into the Gaza Strip. www.logcluster.org Gaza Emergency Daily Report – 31 August 2014 Logistics Gaps and Bottlenecks The Logistics Cluster continues to monitor the impact of the ceasefire on logistics access constraints and the security of humanitarian space for the transportation and distribution of relief supplies. -

Introduction to the Geography of Southwest Asia Name ______Date ______Pd _____

Introduction to the geography of Southwest Asia Name ____________________________________ Date _______________________ Pd _____ Tigris River *begins in Turkey and travel through Syria and Iraq *empties into the Persian GulfThey are the *largest rivers in Southwest Asia *essential source of water Euphrates River *Because of the importance of their waters, they are source of conflict *nations argue over control of this important natural resource Jordan River *forms the border between the nation of Jordan and the Palestinian Territory known as the West Bank. *Control of the Jordan River’s water is a source of dispute between the Palestinians and the Israelis. Suez Canal *connects the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea *it is an important trade route Strait of Hormuz *narrow shallow body of water that connects the Persian Gulf to the Arabian Sea *important trade route connecting the rich oil fields of the gulf to the Arabian Sea and beyond. Arabian Sea *south of Saudi Arabia. *For centuries, the Arabian Sea has been a key link in the Indian Ocean trade and remains a major trade route. Red Sea *sea separating Africa from South West Asia *connects the Arabian Sea to the Mediterranean via the Suez Canal. Gaza Strip *narrow strip of land between Israel, Egypt, and the Mediterranean Sea *Gaza Strip is home to millions of Palestinian Refugees who fled there during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War *frequent conflicts between its Arab inhabitants and Israeli Jews. Introduction to the geography of Southwest Asia Name ____________________________________ Date -

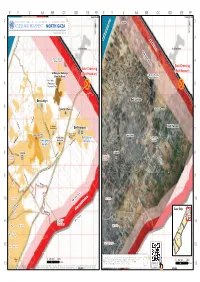

North Gaza ¥ August 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone

No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles 3 nautical miles X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF Yad Mordekhai Yad Mordekhai 2 United Nations OfficeAs-Siafa for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs As-Siafa 2 ACCESS AND MOVEMENT - NORTH GAZA ¥ auGUST 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone Al-Rasheed Netiv ha-Asara Netiv ha-Asara High Risk Zone Temporary Wastewater 4 Treatment Lagoons 4 Erez Crossing Erez Crossing Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Beit Hanoun) (Beit Hanoun) Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) (Umm An-Naser) Beit Lahia 5 Wastewater 5 Treatment Plant Beit Lahiya Beit Lahiya 6 6 'Izbat Beit Hanoun 'Izbat Beit Hanoun Al Mathaf Hotel Al-Sekka Al Karama Al Karama El-Bahar Beit Lahia Main St. Arc-Med Hotel Al-Faloja Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Housing Project Beit Hanoun Madinat al 'Awda 7 v®Madinat al 'Awda 7 Beit Hanoun Jabalia Camp v® Industrial Jabalia Camp 'Arab Maslakh Zone Beit Hanoun 'Arab Maslakh Kamal Edwan Beit Lahya Beit Lahya Abu Ali Eyad Kamal Edwan Hospital Al-Naser Al-Saftawi Hospital Khalil Al-Wazeer Ahmad Sadeq Ash Shati' Camp Said El-Asi Jabalia Jabalia An Naser 8 Al-quds An Naser 8 El-Majadla Ash Sheikh Yousef El-Adama Ash Sheikh Al-Sekka Radwan Radwan Falastin Khalil El-Wazeer Al Deira Hotel Ameen El Husaini Heteen Salah El-Deen ! Al-Yarmook Saleh Dardona Abu Baker Al-Razy Palestine Stadium Al-Shifa Al-Jalaa 9 9 Hospital ! Al-quds Northern Rimal Al-Naffaq Al-Mashahra El-Karama Northern Rimal Omar El-Mokhtar Southern Rimal Al-Wehda Al-Shohada Al Azhar University Ad Daraj G Ad Daraj o v At Tuffah e At Tuffah 10 r 10 n High Risk Zone Islamic ! or Al-Qanal a University Yafa t e Haifa Jamal Abdel Naser Al-Sekka 500 meter NO-Go Zone Salah El-Deen Gaza Strip Beit Lahiya Al-Qahera Khalil Al-Wazeer J" Boundar J" y JabalyaJ" Al-Aqsa As Sabra Gaza City Beit Hanun Gaza City Marzouq GazaJ" City Northern Gaza Al-Dahshan Wire Fence Al 'Umari11 Wastewater 11 Mosque Moshtaha Treatment Plant Tal El Hawa Ijdeedeh Ijdeedeh Deir alJ" Balah Old City Bagdad Old City Rd No. -

ICC-01/18 Date: 16 March 2020 PRE

ICC-01/18-111 17-03-2020 1/10 NM PT Original: English No.: ICC-01/18 Date: 16 March 2020 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER I Before: Judge Péter Kovács, Presiding Judge Judge Marc Perrin de Brichambaut Judge Reine Adélaïde Sophie Alapini-Gansou SITUATION IN THE STATE OF PALESTINE Public Amicus Curiae Submission of Observations Pursuant to Rule 103 Source: Intellectum Scientific Society (hereinafter Intellectum) No. ICC-01/18 1/10 ICC-01/18-111 17-03-2020 2/10 NM PT Document to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to: The Office of the Prosecutor Counsel for the Defence Fatou Bensouda, Prosecutor James Stewart, Deputy Prosecutor Legal Representatives of the Victims Legal Representatives of the Applicants Unrepresented Victims Unrepresented Applicants (Participation/Reparation) The Office of Public Counsel for The Office of Public Counsel for the Victims Defence Paolina Massidda States’ Representatives Amici Curiae The competent authorities of the ▪ Professor John Quigley State of Palestine ▪ Guernica 37 International Justice The competent authorities of the Chambers State of Israel ▪ The European Centre for Law and Justice ▪ Professor Hatem Bazian ▪ The Touro Institute on Human Rights and the Holocaust ▪ The Czech Republic ▪ The Israel Bar Association ▪ Professor Richard Falk ▪ The Organization of Islamic Cooperation ▪ The Lawfare Project, the Institute for NGO Research, Palestinian Media Watch, & the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs ▪ MyAQSA ▪ Professor Eyal Benvenisti ▪ The Federal Republic of Germany ▪ Australia No. ICC-01/18 2/10 ICC-01/18-111 17-03-2020 3/10 NM PT ▪ UK Lawyers for Israel, B’nai B’rith UK, the International Legal Forum, the Jerusalem Initiative and the Simon Wiesenthal Centre ▪ The Palestinian Bar Association ▪ Prof. -

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

Egypt and Israel: Tunnel Neutralization Efforts in Gaza

WL KNO EDGE NCE ISM SA ER IS E A TE N K N O K C E N N T N I S E S J E N A 3 V H A A N H Z И O E P W O I T E D N E Z I A M I C O N O C C I O T N S H O E L C A I N M Z E N O T Egypt and Israel: Tunnel Neutralization Efforts in Gaza LUCAS WINTER Open Source, Foreign Perspective, Underconsidered/Understudied Topics The Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, is an open source research organization of the U.S. Army. It was founded in 1986 as an innovative program that brought together military specialists and civilian academics to focus on military and security topics derived from unclassified, foreign media. Today FMSO maintains this research tradition of special insight and highly collaborative work by conducting unclassified research on foreign perspectives of defense and security issues that are understudied or unconsidered. Author Background Mr. Winter is a Middle East analyst for the Foreign Military Studies Office. He holds a master’s degree in international relations from Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies and was an Arabic Language Flagship Fellow in Damascus, Syria, in 2006–2007. Previous Publication This paper was originally published in the September-December 2017 issue of Engineer: the Professional Bulletin for Army Engineers. It is being posted on the Foreign Military Studies Office website with permission from the publisher. FMSO has provided some editing, format, and graphics to this paper to conform to organizational standards.