Operation of The. TRADE AGREEMENTS PROGRAM June 1934 to April 1948 Part I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

Nazi Privatization in 1930S Germany1 by GERMÀ BEL

Economic History Review (2009) Against the mainstream: Nazi privatization in 1930s Germany1 By GERMÀ BEL Nationalization was particularly important in the early 1930s in Germany.The state took over a large industrial concern, large commercial banks, and other minor firms. In the mid-1930s, the Nazi regime transferred public ownership to the private sector. In doing so, they went against the mainstream trends in western capitalistic countries, none of which systematically reprivatized firms during the 1930s. Privatization was used as a political tool to enhance support for the government and for the Nazi Party. In addition, growing financial restrictions because of the cost of the rearmament programme provided additional motivations for privatization. rivatization of large parts of the public sector was one of the defining policies Pof the last quarter of the twentieth century. Most scholars have understood privatization as the transfer of government-owned firms and assets to the private sector,2 as well as the delegation to the private sector of the delivery of services previously delivered by the public sector.3 Other scholars have adopted a much broader meaning of privatization, including (besides transfer of public assets and delegation of public services) deregulation, as well as the private funding of services previously delivered without charging the users.4 In any case, modern privatization has been usually accompanied by the removal of state direction and a reliance on the free market. Thus, privatization and market liberalization have usually gone together. Privatizations in Chile and the UK, which began to be implemented in the 1970s and 1980s, are usually considered the first privatization policies in modern history.5 A few researchers have found earlier instances. -

Presentation Slides

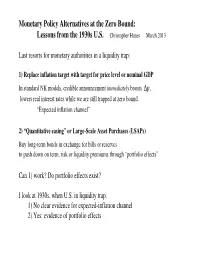

Monetary Policy Alternatives at the Zero Bound: Lessons from the 1930s U.S. Christopher Hanes March 2013 Last resorts for monetary authorities in a liquidity trap: 1) Replace inflation target with target for price level or nominal GDP In standard NK models, credible announcement immediately boosts ∆p, lowers real interest rates while we are still trapped at zero bound. “Expected inflation channel” 2) “Quantitative easing” or Large-Scale Asset Purchases (LSAPs) Buy long-term bonds in exchange for bills or reserves to push down on term, risk or liquidity premiums through “portfolio effects” Can 1) work? Do portfolio effects exist? I look at 1930s, when U.S. in liquidity trap. 1) No clear evidence for expected-inflation channel 2) Yes: evidence of portfolio effects Expected-inflation channel: theory Lessons from the 1930s U.S. β New-Keynesian Phillips curve: ∆p ' E ∆p % (y&y n) t t t%1 γ t T β a distant horizon T ∆p ' E [∆p % (y&y n) ] t t t%T λ j t%τ τ'0 n To hit price-level or $AD target, authorities must boost future (y&y )t%τ For any given path of y in near future, while we are still in liquidity trap, that raises current ∆pt , reduces rt , raises yt , lifts us out of trap Why it might fail: - expectations not so forward-looking, rational - promise not credible Svensson’s “Foolproof Way” out of liquidity trap: peg to depreciated exchange rate “a conspicuous commitment to a higher price level in the future” Expected-inflation channel: 1930s experience Lessons from the 1930s U.S. -

Hitler's American Model

Hitler’s American Model The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law James Q. Whitman Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford 1 Introduction This jurisprudence would suit us perfectly, with a single exception. Over there they have in mind, practically speaking, only coloreds and half-coloreds, which includes mestizos and mulattoes; but the Jews, who are also of interest to us, are not reckoned among the coloreds. —Roland Freisler, June 5, 1934 On June 5, 1934, about a year and a half after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of the Reich, the leading lawyers of Nazi Germany gathered at a meeting to plan what would become the Nuremberg Laws, the notorious anti-Jewish legislation of the Nazi race regime. The meeting was chaired by Franz Gürtner, the Reich Minister of Justice, and attended by officials who in the coming years would play central roles in the persecution of Germany’s Jews. Among those present was Bernhard Lösener, one of the principal draftsmen of the Nuremberg Laws; and the terrifying Roland Freisler, later President of the Nazi People’s Court and a man whose name has endured as a byword for twentieth-century judicial savagery. The meeting was an important one, and a stenographer was present to record a verbatim transcript, to be preserved by the ever-diligent Nazi bureaucracy as a record of a crucial moment in the creation of the new race regime. That transcript reveals the startling fact that is my point of departure in this study: the meeting involved detailed and lengthy discussions of the law of the United States. -

Revision Booklet – Germany

GERMANY IN TRANSITION, 1919-1939 There are seven key issues to learn: 1. What challenges were faced by the Weimar Republic from 1919-1923? 2. Why were the Stresemann years considered a ‘golden age’? 3. How and why did the Weimar Republic collapse between 1929 and 1933? 4. How did the Nazis consolidate their power between 1933 and 1934? 5. How did Nazi economic, social and racial policy affect life in Germany? 6. What methods did the Nazis use to control Germany? 7. What factors led to the outbreak of war in 1939? 1. What challenges were faced by the Weimar Republic from 1919 to 1923? ★ The Weimar Republic was Germany’s new democratic government after WW1. Faced many problems in the first few years of power. ★ Following Germany’s surrender, many people were unhappy and disillusioned. ★ The terms of the Versailles Treaty were very harsh. Germans felt betrayed, bitter and desperate for revenge. ★ Weimar faced challenges to its power: Spartacist Uprising, Kapp Putsch, Munich Putsch, the Ruhr Crisis ★ Hyperinflation Key words Weimar Republic Democracy Coalition Treaty Reparations KPD Spartacists Communists Putsch Kapp Ruhr Passive resistance Hyperinflation 2. Weimar recovers! Was the period 1924 to 1929 a ‘golden age’? ★ The economy recovered: Dawes Plan; a new currency called the Rentenmark; the Young Plan; too dependent on US loans? ★ A number of successes abroad: the Locarno Pact; the League of Nations; the Kellogg- Briand Pact; the role of Stesemann. ★ Political developments: support for the moderate parties; lack of support for the extremist parties. ★ Social developments: improved standard of living (housing, wages, unemployment insurance); the status of women improved; cultural changes Key words Dawes Plan Recovery Locarno League of Nations Kellogg-Briand Stresemann 3. -

Link to Nazi Control KO

Eight Steps to Becoming Dictator (Rigged German Election Leads To Psychopath Nazi Nazi Control Assessment 3 Fuhrer) 1 Reichstag Fire - 27 Feb 1933 If you are asked about how Hitler The Reichstag (the German Parliament) burned down. Hitler used it as an consolidated his power, remember that the question is not just about excuse to arrest many of his Communist opponents, and as a major platform describing what happened and what R in his election campaign of March 1933. The fire was so convenient that Hitler did. You should many people at the time claimed that the Nazis had burned it down, and then explain how Hitler's actions helped him just blamed the Communists. to consolidate his power - it is more 2 General Election - 5 March 1933 about the effects of what he did. The Hitler held a general election, appealing to the German people to give him a table below describes how certain events that happened between 1933 and G clear mandate. Only 44% of the people voted Nazi, which did not give him a 1934 gave Hitler the opportunity to majority in the Reichstag, so Hitler arrested the 81 Communist deputies consolidate power. (which did give him a majority). Goering become Speaker of the Reichstag. 3 Enabling Act - 23 March 1933 The Reichstag voted to give Hitler the power to make his own laws. Nazi stormtroopers stopped opposition deputies going in, and beat up anyone who E dared to speak against it. The Enabling Act made Hitler the dictator of The Police State Germany, with power to do anything he liked - legally. -

Droughts of 1930-34

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director Water-Supply Paper 680 DROUGHTS OF 1930-34 BY JOHN C. UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1936 i'For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 20 cents CONTENTS Page Introduction ________ _________-_--_____-_-__---___-__________ 1 Droughts of 1930 and 1931_____._______________________ 5 Causes_____________________________________________________ 6 Precipitation. ____________________________________________ 6 Temperature ____________-_----_--_-_---___-_-_-_-_---_-_- 11 Wind.._.. _ 11 Effect on ground and surface water____________________________ 11 General effect___________________________________________ 11 Ground water___________________________ _ _____________ _ 22 Surface water___________________________________________ 26 Damage___ _-___---_-_------------__---------___-----_----_ 32 Vegetation.____________________________________________ 32 Domestic and industrial water supplies_____________________ 36 Health____-_--___________--_-_---_-----_-----_-_-_--_.__- 37 Power.______________________________________________ 38 Navigation._-_-----_-_____-_-_-_-_--__--_------_____--___ 39 Recreation and wild life--___--_---__--_-------------_--_-__ 41 Relief - ---- . 41 Drought of 1934__ 46 Causes_ _ ___________________________________________________ 46 Precipitation.____________________________________________ 47 Temperature._____________---_-___----_________-_________ 50 Wind_____________________________________________ -

1934 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30 1934 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1934 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington. D.C. - - - - Price 15 cents FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION GARLAND S. FERGUSON, Jr., Chairman 1 EWIN L. DAVIS, Vice Chairman CHARLES H. MARCH WILLIAM A. AYRES OTIS B. JOHNSON, Secretary 1 Chairmanship rotates annually. Commissioner Davis will become chairman in January 1935. FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSIONERS--1915-34 Name State from which appointed Period of service Joseph E. Davies Wisconsin Mar.16, 1915-Mar. 18, 1918. William J. Harris Georgia Mar.16, 1915-May 31, 1918. Edward N. Hurley Illinois Mar.16, 1915-Jan. 31, 1917. Will H. Parry Washington Mar.16, 1915-A p r. 21, 1917. George Rublee New Hampshire Mar.16, 1915-May 14, 1916. William B. Colver Minnesota Mar.16, 1917-Sept. 25, 1920. John Franklin Fort New Jersey Mar. 16, 1917-Nov. 30,1919. Victor Murdock Kansas Sept. 4, 1917-Jan. 31, 1924. Huston Thompson Colorado Jan. 17, 1919-Sept. 25, 1926. Nelson B. Gaskill New Jersey Feb. l. 1921-Feb. 24, 1925. John Garland Pollard Virginia Mar. 6, 1920-Sept. 25, 1921. John F. Nugent Idaho Jan.15, 1921-Sept. 25, 1927. Vernon W. Van Fleet Indiana June 26, 1922-July 31, 1926. Charles W. Hunt Iowa June 16, 1924-Sept. 25,1932. William E. Humphrey Washington Feb.25, 1925-Oct. 7, 1933. Abram F. Myers Iowa Aug. 2, 1925-Jan. 15, 1929. Edgar A. McCulloch Arkansas Feb.11, 1927-Jan. 23, 1933. Garland S. Ferguson, Jr. -

Semester 1 Life in Nazi Germany 1933

Box A: Key words and definitions Box C: Hitler’s steps to power 1933 - 1935 Box B: Nazi Beliefs 1. Germany was still suffering from World War One with 6 million 1. Aryan – Blonde, Blue eyes, ‘superior’ race 1. Bread and work for all unemployed people and an economic depression. 2. Untermenschen – lower races e.g. Jews 2. Destroy Communism 2. 1932 – The Nazis won 230 seats in the Reichstag elections 3. Ubermenschen - superior races e.g. Germans 3. Get rid of the Jews 3. 1933 – Hitler persuaded von Papen and Hindenburg to make 4. Censorship – limiting the information people have access to 4. Ensure Racial supremacy him Chancellor of Germany. Hindenburg was still president. 5. Indoctrination – to brainwash 5. Fight for Lebensraum 4. 1933- Hitler called more elections. This time he used the SA to 6. Reichstag – German Parliament 6. Strengthen the Government intimidate opponents. 7. Communism – A political party, main enemy of the Nazi’s politically 7. Nationalise important industries 5. The Reichstag Fire - Feb 1933 – Blamed on a communist called 8. SA – brown shirts 8. Improve Education Van Der Lubbe. This made people dislike communists. Van Der 9. SS – Hitler’s bodyguard Lubbe was executed. 10. Gestapo – Secret police 6. Reichstag Fire Decree – it had 6 parts. One of them limited 11. Lebensraum – Living Space for German people Year 11: Semester 1 people’s rights, meaning they could be arrested with out trial 12. Gleichshaltung – Brining Germany into line and limited freedom of speech. The government was given 13. Trade union – an organisation which fights for worker’s rights Life in Nazi Germany 1933 - 1939 more power and there were harsh punishments for arson, 14. -

Friendly Endeavor, June 1934

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Northwest Yearly Meeting of Friends Church Friendly Endeavor (Quakers) 6-1934 Friendly Endeavor, June 1934 George Fox University Archives Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/nwym_endeavor Recommended Citation George Fox University Archives, "Friendly Endeavor, June 1934" (1934). Friendly Endeavor. 141. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/nwym_endeavor/141 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Northwest Yearly Meeting of Friends Church (Quakers) at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Friendly Endeavor by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Friendly Endeavor Volume 13, Number PORTLAND, OREGON June, 1934. "BUILDERS" 1934 ANNUAL BANQUET REPORT W a l t e r P . L e e I am sure none of the 345 Christian (Given at the 11th annual Twin Rocks Endeavorei's who attended the Confer Conference Banquet April 28, 1934) Hello, everybody! Well, Boise is ence Rally Banquet, April 28th, at the The honor of addressing; a group of back in print again. We finally have Sunnyside Friends Church left with a great architects and builders would not decided to break our silence and remind lack of enthusiasm, for interest in our be beneath the dignity of the President you that Boise is still on the map. coming Conference ran high throughout of the United States. How profoundly However, just because you have not the whole evening. The program o u r l i v e s h a v e b e e n a f f e c t e d b y t h e h e a r d f r o m u s d o e s n o t m e a n w e h a v e seemed planned to remind us of all the builders, men who build colossal man not been doing anything. -

SURVEY of CURRENT BUSINESS June 1934

JUNE 1934 SURVEY OF UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE BUREAU OF FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC COMMERCE WASHINGTON VOLUME 14 NUMBER 6 The usual SEMIANNUAL i?EVISION of material has been made in this issue. A list of the new data added and the series dropped is given below. The pages indicated for the new series refer to this issue, while the pages given for the discontinued series refer to the May 1934 issue. DATA ADDED DATA DROPPED Page Page Agricultural products, cash income received from Marketings of forest products 23 marketings of 23 Highway construction under the Federal Highway Act 25 Index of new passenger car sales 26 Delinquent accounts of the electrical trade 26 Indexes of variety store sales (new index) 26 Indexes of five-and-ten (variety) store sales (old index) 26 Factory employment (B.L.S.) 27 Restaurant sales and stores operated 27 Factory pay rolls (B.L.S.) 29 Childs Company. J. R. Thompson Company. Waldorf System, Inc. Agricultural loans outstanding (6 series) 30 Factory employment (adjusted and unadjusted) Imports for consumption-^ „ _ ^ _ 34 (F.R.B.) 27 Factory operations, proportion of full time worked. 28 Beverages . 39 Nonmanufacturing employment, canning and pre- Fermented malt liquors: serving. 28 Production, consumption, and stocks. Factory pay-roll indexes (F.R.B.) 29 Distilled spirits: Production, consumption, and stocks in Nonmanufacturing pay rolls, canning and preserv- bonded warehouses. ing „ 29 Bank suspensions 31 Receipts of milk, Greater New York 40 Receipts of milk, Greater New York 39 Refined sugar, imports -

SURVEY of CURRENT BUSINESS June 1935

JUNE 1935 SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE BUREAU OF FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC COMMERCE WASHINGTON VOLUME 15 NUMBER 6 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE DANIEL C. ROPER, Secretary BUREAU OF FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC COMMERCE CLAUDIUS T. MURCHISON, Director SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS Prepared in the DIVISION OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH H. GORDON HAYES, Chief M. JOSEPH MEEHAN, Editor Volume 15 JUNE 1935 Number 6 CONTENTS SUMMARIES AND CHARTS STATISTICAL DATA—Continued Page Business indicators 2 Monthly business statistics: Page Business situation summarized 3 Business indexes 22 Comparison of principal data, 1931-35 4 Commodity prices 23 Commodity prices 5 Construction and real estate 24 Domestic trade 6 Domestic trade 25 Employment 7 Employment conditions and wages 27 Finance 8 Finance 30 Foreign trade 9 Foreign trade 34 Real estate and construction 10 Transportation and communications 35 Transportation 11 Statistics on individual industries: Survey of individual industries: Chemicals and allied products 36 Automobiles and rubber 12 Electric power and gas 39 Forest products , 13 Foodstuffs and tobacco 39 Iron and steel 14 Fuels and byproducts 43 Textiles 15 Leather and products 44 Lumber and manufactures 45 SPECIAL ARTICLE Metal and manufactures: Current trends in the cotton industry 16 Iron and steel 46 Machinery and apparatus 48 STATISTICAL^ DATA Nonferrous metals and products 49 Paper and printing 50 New and revised series: Rubber and products 51 New series: Wholesale price of wheat, No. 1 dark northern Spring Minneapolis; shipments and stocks of structural clay prod- Stone, clay, and glass products 52 ucts; and rayon deliveries 19, 20 Textile products 53 Revised series: Indexes of department store sales and produc- Transportation equipment 55 tion of goat and kid and sheep and lamb leathers.