The Cliffs of Dover and England

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Definition of Chalk

1.1: Introduction: 1.1.1: Definition of chalk: Chalk is a soft, white, porous sedimentary carbonate rock, a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite. Calcite is calcium carbonate or CaCO3. It forms under reasonably deep marine conditions from the gradual accumulation of minute calcite shells (coccoliths) shed from micro-organisms called coccolithophores. Flint (a type of chert unique to chalk) is very common as bands parallel to the bedding or as nodules embedded in chalk. It is probably derived from sponge spicules or other siliceous organisms as water is expelled upwards during compaction. Flint is often deposited around larger fossils such as Echinoidea which may be silicified (i.e. replaced molecule by molecule by flint). Chalk as seen in Cretaceous deposits of Western Europe is unusual among sedimentary limestone in the thickness of the beds. Most cliffs of chalk have very few obvious bedding planes unlike most thick sequences of limestone such as the Carboniferous Limestone or the Jurassic oolitic limestones. This presumably indicates very stable conditions over tens of millions of years. Figure (1-1): Calcium sulphate 1 "Nitzana Chalk curves" situated at Western Negev, Israel are chalk deposits formed at the Mesozoic era's Tethys Ocean Chalk has greater resistance to weathering and slumping than the clays with which it is usually associated, thus forming tall steep cliffs where chalk ridges meet the sea. Chalk hills, known as chalk downland, usually form where bands of chalk reach the surface at an angle, so forming a scarp slope. Because chalk is well jointed it can hold a large volume of ground water, providing a natural reservoir that releases water slowly through dry seasons. -

Walking to the White Cliffs of Dover

Walking to The White Cliffs of Dover The White Cliffs of Dover, Take a walk through Dover, Langdon Cliffs, Upper Road, past the museum and along the Dover seafront to the iconic White Cliffs. On your way you'll see the historic TRAIL medieval castle while viewing the Walking hustle and bustle of the world's busiest passenger port. When GRADE you get to the cliffs, call in to our Moderate visitor centre to collect a free walking map and grab a bite to DISTANCE eat or treat yourself to something 2 miles (3.3km) from our shop. TIME Terrain 50 The walk is mostly on paved surfaces with some steps; mostly flat, with one very steep section. The route is challenging with a pushchair. OS MAP 138 Things to see Contact 01304 207326 [email protected] Facilities The White Cliffs are open to walkers free of charge everyday of the year. Dover Museum The seafront The Port of Dover The cafe, gift shop and toilets Why not visit Dover Museum? Enjoy views of the harbour and Take a moment to look at the are open daily 10-5pm, March The museum has a fascinating castle. From the promenade you’ll bustle of the port below you. to October with shorter hours in collection of items from the be able to see the ships coming Ferries arrive and depart 24hrs winter. local area, including the world's and going from the ferry terminal a day traveling to France and A short walk from the visitor oldest seagoing vessel the Dover and may even see a giant cruise Belgium. -

Chemistry of Chalk and Mgco3, Explored Through the Sport of Weightlifting

Teacher Notes: Chemistry of chalk and MgCO3, explored through the sport of weightlifting Sport: Weightlifting Age group: 11 - 14 These notes are designed as a guide on how to lead the session, and are written in a script format. If you wish to lead the session in a different way please feel free to do so. The red text indicates what each slide includes, while the blue text highlights the key points being discussed in each slide. The owl symbol demonstrates where students are required to perform a task (eg questions, experiment, etc.). These are used to help you observe the students learning and recap any information which the students have found difficult to understand. Depending on the level of student understanding this module may require two lessons to complete. Slide 1 Opening slide The first slide provides the title of the session and a picture of a weightlifter dusting chalk containing title of off his hands, introducing the topic and drawing a visual picture of the link between the session and background sport and chemistry. picture as a visual introduction. Slides 2 & 5 – Introduction – Weightlifting and the link to chemistry Weightlifting, the sport of lifting weights in a variety of ways to a variety of different positions, has routes back to ancient times, with the lifting of heavy stones to determine a person’s strength. This has continued through the ages and in many strongman contests today heavy stones are lifted, or attempted to be lifted. Slide 2 gives a small amount of Weightlifting as we know of it today started in Germany in the mid-1800s and quickly background to spread through the rest of Continental Europe. -

08 Feb 2021 Eindrucksvolle Wahrzeichen an Englands Küste

Eindrucksvolle Wahrzeichen an Englands Küste Leuchttürme faszinieren. Sie sind romantisch schön, symbolisieren Weite und Freiheit, sind Landmarken für Schiffe, geben Orientierung und weisen den Weg. Wer sich aus der aktuellen Situation schon einmal „wegträumen“ möchte, wird an Englands Küste leicht fündig und kann interessante Wanderungen häufig von Turm zu Turm planen. „Weit über 60 Leuchttürme reihen sich, einer Perlenschnur gleich, entlang der reizvollen und abwechslungsreichen Küste, viele von ihnen sind der Öffentlichkeit zugänglich“, sagt Samantha Richardson, Direktorin der National Coastal Tourism Academy, die das Projekt „England’s Coast“ leitet. „Die Türme stehen abseits üblicher Touristenpfade, eignen sich wunderbar als Fotomotive und in einigen kann man sogar übernachten – weit weg vom Alltag und inmitten traumhaft einsamer Küstenlandschaften. Und sobald die Einschränkungen es zulassen, machen sie eine Reise an die Küste zu einem magischen Besuch“, so Richardson. England’s Coast ist ein Zusammenschluss aller acht englischen Küstenregionen, die mit dem Projekt ihre Kultur, sagenreiche Geschichte und malerischen Küstenlandschaften vermarkten. Auf Flamborough Head, einer Halbinsel zwischen den Buchten Filey und Bridlington in der Grafschaft Yorkshire, stehen gleich zwei Leuchttürme. Der unter Denkmalschutz stehende Kreideturm aus dem Jahr 1669 ist einer der ältesten vollständig erhaltenen Leuchttürme Englands. Unweit hiervon wurde 1806 ein zweiter Turm erbaut. An den unter Naturschutz stehenden Klippen nisten rund um die Türme über 200.000 Seevögel, darunter Basstölpel und Papageientaucher. Der älteste Leuchtturm des Landes und einer der ältesten der Welt steht auf dem Gelände von Dover Castle. Der Turm wurde um das Jahr 43 n. Chr. von den Römern erbaut, als Navigationshilfe zur Überquerung des Ärmelkanals. Die gut erhaltene Ruine ist ein schönes Fotomotiv und steht direkt neben der kleinen Kirche St. -

Educator Materials (PDF)

Written in Chalk Phenomenal Image Educator Materials HOW TO USE THIS RESOURCE The images for this resource, showing the chalk cliffs of Dover, England, and the microscopic skeletons of coccolithophore algae, can serve as an anchoring phenomenon to explore the key concepts described below. The pedagogical practice of using phenomena to provide a context for understanding science concepts and topics is an implementation practice supported by the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). Phenomena are observable occurrences that students can use to generate science questions for further investigation or to design solutions to problems that drive learning. In this way, phenomena connect learning with what is happening in the world while providing students with the opportunity to apply knowledge while they are building it. The “Implementation Suggestions” and “Teaching Tips” sections provide options for incorporating the images into a curriculum or unit of study and can be modified to use as a standalone activity or to supplement an existing lesson. The student handout includes reproductions of the images and the “Background Information” section. KEY CONCEPTS A. Environmental factors such as topography, temperature, and ocean pH can determine the ability of microscopic algae to survive and reproduce over the geologic timescale. B. Specific biological processes, geologic internal processes (tectonic uplift), and surface processes (weathering and erosion) are causal agents in building up and wearing down the Cliffs of Dover over time. C. The geologic record found in the chalk cliffs of Dover can help predict the future effects of climate change on the chemical composition (e.g., ocean pH) and biodiversity of the oceans. -

Uk-England-South-Coast-Self-Drive

Take to the South Coast on this incredible 5-day road trip of England’s seaside towns, from the White Cliffs of Dover to the charming Brighton and the wonderful Isle of Wight. Set out from Heathrow Airport to discover where English soil meets the Channel, encountering the villages and towns that have shaped counties from Kent and Sussex to Hampshire and Dorset. You’ll also get the chance to visit the Isle of Wight and put your feet up in this endearing holiday spot before continuing on to Bournemouth and wider Dorset. dover to dorset 2 | drivenow.com.au – Helping travellers find the best deals on campervan and car rental since 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 DAY 1: Heathrow - Dover 5 DAY 2: Dover - Rye - Brighton 6 DAY 3: Brighton - Portsmouth - Isle of Wight 7 DAY 4: Isle of Wight - Bournemouth 8 DAY 5: Bournemouth - Dorchester - Weymouth 9 CONCLUSION 3 | drivenow.com.au – Helping travellers find the best deals on campervan and car rental since 2003 day Heathrow - Dover (1 hour, 45 minutes) 1 Finding the right car for your South Coast road trip is easy with DriveNow. Simply select the type of vehicle N you want, pick your dates and let DriveNow do all the NW NE hard work and find you the best deals for your trip. W E This means that when you touch down at Heathrow, SW SE all you have to do is rock on up to your hire car firm, S pick up the keys and jump behind the wheel. You’ll be skirting around the boundary of London on the M25 before following the M20 south to Dover. -

Cultura E Civiltà the White Cliffs of Dover Trascrizione the White Cliffs of Dover Form Part of the Coastline of England Facing

Cultura e Civiltà The White Cliffs of Dover Trascrizione The White Cliffs of Dover form part of the coastline of England facing France. The cliffs are as high as 350 feet in some places. They have a striking appearance because the cliff face is made of chalk with streaks of black flint. Thousands of years ago, the whole area was under the sea. Lots of very small sea creatures died and over the years their bones and shells were pressed together and became chalk. They gradually rose up, becoming white cliffs. Erosion from the seawater keeps the cliffs white and where the sea cannot reach them, they are covered by vegetation. The White Cliffs of Dover are often considered a symbol of England because they are the last sight that travelers see when they leave England, and the first thing they see when they arrive. In fact, at the point where they rise, England is only 21 miles from the French coast. These cliffs were an important part of the defenses of Britain during both World Wars. However, their importance goes much farther back in history. The White Cliffs of Dover stood tall through several invasion attempts, from Julius Caesar in 55 BC to Hitler’s Nazis in 1940. Under the Romans, the Cliffs were used as the base for a lighthouse. In the Middle Ages, Dover Castle, nicknamed ‘The Key to England’ because of its strategic location, was built there. It is the largest castle in England. During the Napoleonic Wars, prisoners of the castle carved secret tunnels under the Cliffs, which Winston Churchill later used as his World War II headquarters. -

Walking & Cycling Leaflet with Maps

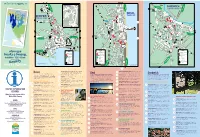

– cliffs country.org.uk white R ic Whitfield Hill h GAZEN SALTS CLIFFS & CASTLES CYCLE ROUTE 1 b S o NATURE a r o C n RESERVE T u WHITFIELD d o h g o l Canterbury e h l w London e R A2 g n M o CLIFFS & CASTLES e R a a SANDWICH R r d d t i CYCLE ROUTE 1 o n S th Menzies Road a r a o ne d Ark La N P red f t Al r e e St TOWN MAP n tr Dolphi i S are n er Squ M et c P 4 Honeywood Rd e i d d s THE SANDWICH WAY a Dover Transport d s A257 TO CYCLE ROUTE 15 o l T e St S e Exchang R w E t CANTERBURY Museum D w S n r o r e o N t & LONDON R e e r R t eet A e . t tr E s S H et e t e e e tr H r G S s o T r t Dover District e i iffin i S g t T d A W d C aR c h t W 5 a Council Offices h F a o e G o S r o b S N o e O Silver St a t R e r l r M e P t r E e e l t S t s e L A DEAL s o a t S RIVER STOUR R S h I n R W Golden St g 6 5 c 7 t s o Tesco e N e s S r w r t St O a O S e t B t d u m T r r e T Dover e a e e h e t t TOWN MAP 6 A2 t a e S R r C 5 Extra e i c t r t r 2 a e F h e r V t A S S i e E c k Parkway u t a D M r Laner t e a i g e d e e e d St t y pin r p t o l C t r Melbourne Avenue e e d e S a e 8 o G S R r g u h n t i l o t d i n c - r S n i count d t U l U e n St io H r n e p R D R d t u w Dover District e w e o Lane r e i e t B s o o g B l f e L k h B S r c Leisure Centre e i t t S r r h e S t t Potter St. -

Volunteer Role Summary Livestock Lookering

Volunteer Role Summary Livestock Lookering Lookers are reliable people who love spending time outdoors and want to help look after the livestock that maintain our amazing chalk grassland. They make sure that the sheep, horses and cows that graze the partnership area are healthy and report any problems to a member of staff. Up on the Downs work in partnership with Kent Wildlife Trust, National Trust and White Cliffs Countryside Partnership and look after over 500 hectares of chalk grassland in the Dover and Folkestone area. We need to use livestock to graze these sites to make sure that this grassland has rich and varied wildlife. With such a large area to look after and 10 or more herds of cows or flocks of sheep needing to be looked after at any one time we are dependent upon the hard work of volunteers to help us make sure that animals are in good condition. By getting involved, you could… Ensure that the highest possible animal welfare standards are being maintained Make a real difference to how the landscape is managed for future generations Spend more time outside and active Working alongside dedicated countryside management professionals, learning skills along the way Join a friendly and varied team and make some new friends What’s involved? You will work on a rota with other volunteers and will be asked to go to a specific site on a particular day and: Check the right number of animals are present Get close enough to tell whether they are healthy Check that water is provided and that ice is broken in freezing weather Report any problems with fencing, gates or paths Report back to staff to let them know you have checked the animals This is a voluntary role. -

National Trust Cottages Access Statement

White Cliffs of Dover Access Statement Upper Road, Dover, Kent, CT16 1HJ T: 01304 207326 E: [email protected] Introduction 1. The Visitor Centre is fully wheelchair friendly with an accessible toilet and adjacent parking 2. Mobile phone reception varies across the property but is generally acceptable near the Visitor Centre. 3. Assistance dogs are welcome throughout the site including the Visitor Centre, where a water bowl is provided. 4. There is a 400 metre accessible path from the blue badge parking which is suitable for some wheelchair users (please see below) that leads to a viewing point of the cliffs with seats available 5. If you require specific information please call us before your visit or on arrival at the car park Arrival & Parking Facilities 1. The site is on the eastern side of Dover, 1 mile from Dover Castle on Upper Road. There are brown signs to the site from the A2/A258 2. A welcome map is available on arrival. Please ask the car park attendant if you need specific help while you are onsite. 3. There are 6 designated blue badge parking spaces opposite the Visitor Centre which have a view of the port. These spaces do not have level access to the Visitor Centre. The main Visitor Centre car park has 14 blue badge spaces which have level access to the Visitor Centre. 4. Blue badge spaces are all on a level tarmac surface. 5. Our other car parks are either gravel or grass and can only be accessed by a steep hill. 6. -

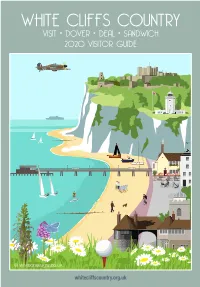

Tourism Guide 2020

WHITE CLIFFS COUNTRY VISIT • DOVER • DEAL • SANDWICH 2020 VISITOR GUIDE © whiteonesugar.co.uk www.whiteonesugar.co.uk whitecliffscountry.org.uk © nigel wallace WHITE WELCOME CLIFFS COUNTRY DOVER • DEAL • SANDWICH Welcome to White Cliffs Country, a unique CONTENTS place where coast meets country, beauty Welcome................................................... 1 Ten Reasons to Visit.................................. 2 meets history, tranquil meets active and The 149th Open....................................... 4 HISTORIC DOVER England meets Europe. Historic Dover........................................ 6 Maritime Deal............................................ 8 The world-famous White Cliffs and our Medieval Sandwich................................... 10 beautiful coast and countryside offer Splendid Coastline.................................... 12 Unique Countryside.................................. 14 spectacular walking, sailing, cycling, golf Magnificent Castles & Forts...................... 16 and sightseeing as well as white knuckle RIB Gateway to Britain.................................... 18 rides, seal spotting and even the opportunity Proud Industrial History............................. 20 to feed a tiger. Maritime History........................................ 22 Hidden Gems........................................... 24 The rich heritage of the area is awe- Blooming Gardens & Parks...................... 26 Adventures on Water, Land & Air.............. 28 inspiring with an amazing selection of diverse museums and a busy -

There'll Be Bluebirds Over, the White Cliffs of Dover, Tomorrow, Just You Wait and See

ABC0000011216 Air Cadet March Book White Cliff of Dover During the Battle of Britain, the Luftwaffe gaged several air strikes against numerous targets in Great Britain. Their normal flight path took them over the white cliffs of Dover. This song was meant as encouragement for the British in their darkest moments in the Battle of Britain, giving them hope of seeing Bluebirds over the White Cliffs of Dover instead of the Luftwaffe. Of particular interest is the line "Jimmy will go to sleep in his own room again..". It meant little Jimmy, who slept outside in an air raid shelter most of the time, might get to sleep in his own room again when the war was over. Interestingly enough, the air raid shelter Jimmy slept in was destroyed by a direct hit one morning, but for some reason Jimmy and his!f_amily had decided to sleep in the house that night and nobody was hurt. There'll be bluebirds over, The white cliffs of Dover, Tomorrow, just you wait and see. There'll be love and laughter, And peace ever after, Tomorrow, when the world is free. The shepherd will tend his sheep, The valley will bloom again, And Jimmy will go to sleep in his own little room again. There'll be bluebirds over, The white cliffs of Dover, Tomorrow, just you wait and see. Page 61-1 . ..- ABC0000011217 Air Cadet March Book White Cliffs of Dover WHITE CLIFFS OF DOVER Bb CONDUCTOR SLOW MARCH or INSPECTION TUNE A-_._ , I p p ! .._.-, , J .tJ -J,t j B B_._ , , , , I I j i J _.J J J I j : D _4 I ,j _' .,I !: t I J ] g PERC " "_4 i', _, _ , _ s :! 7,, :g.,.j, ] _J;_ .,_ Ij -J-J _J ;J F i" " i# _, j j o J jj., _ _ j j jJ h -# d d _Jdd 2 J_ d dJ _ _d: J.,,i'=, t t t t.