Bermudez, Masters of Arts, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Season 2014-2015

23 Season 2014-2015 Wednesday, January 28, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, January 30, at 2:00 Saturday, January 31, Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor at 8:00 Kirill Gerstein Piano Beethoven Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 I. Allegro con brio II. Andante con moto III. Allegro— IV. Allegro Intermission Shostakovich Piano Concerto No. 2 in F major, Op. 102 I. Allegro II. Andante III. Allegro Shostakovich/from Suite from The Gadfly, Op. 97a: arr. Atovmyan I. Overture: Moderato con moto III. People’s Holiday: [Allegro vivace] VII. Prelude: Andantino XI. Scene: Moderato This program runs approximately 1 hour, 40 minutes. The January 28 concert is sponsored by MEDCOMP. designates a work that is part of the 40/40 Project, which features pieces not performed on subscription concerts in at least 40 years. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 Please join us immediately following the January 30 concert for a Chamber Postlude, featuring members of The Philadelphia Orchestra. Brahms Piano Quartet No. 3 in C minor, Op. 60 I. Allegro non troppo II. Scherzo: Allegro III. Andante IV. Finale: Allegro lomodo Mark Livshits Piano Kimberly Fisher Violin Kirsten Johnson Viola John Koen Cello 3 Story Title 25 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra is one of the preeminent orchestras in the world, renowned for its distinctive sound, desired for its keen ability to capture the hearts and imaginations of audiences, and admired for a legacy of imagination and innovation on and off the concert stage. -

20Th-Century Repertory

Mikrokosmos List 650. - 2 - October 2019 ....20TH-CENTURY REPERTORY 1 Absil: Clarinet Quartet/Pelemans, Willem: Clar Quartet/Cabus, Peter: Clar ZEPHYR Z 18 A 10 Quartet/Moscheles: Prelude et fugue - Belgian Clarinet Quartet (p.1982) S 2 Albrecht, Georg von: 2 Piano Sonatas; Prelude & Fugue; 3 Hymns; 5 Ostliche DA CAMERA SM 93141 A 8 Volkslieder - K.Lautner pno 1975 S 3 Alpaerts, Flor: James Ensor Suite/Mortelmans: In Memoriam/E.van der Eycken: DECCA 173019 A 8 Poeme, Refereynen - cond.Weemaels, Gras, Eycken S 4 Amelsvoort: 2 Elegies/Reger: Serenade/Krommer-Kramar: Partita EUROSOUND ES 46442 A 15 Op.71/Triebensee: Haydn Vars - Brabant Wind Ensemble 1979 S 5 Antoine, Georges: Pno Quartet Op.6; Vln Sonata Op.3 - French String Trio, MUSIQUE EN MW 19 A 8 Pludermacher pno (p.1975) S 6 Badings: Capriccio for Vln & 2 Sound Tracks; Genese; Evolutions/ Raaijmakers: EPIC LC. 3759 A 15 Contrasts (all electronic music) (gold label, US) 7 Baervoets: Vla Con/P.-B.Michel: Oscillonance (2 vlns, pno)/C.Schmit: Preludes for EMI A063 23989 A 8 Orch - Patigny vla, Pingen, Quatacker vln, cond.Defossez (p.1980) S 8 Baily, Jean: 3 Movements (hn, tpt, pf, string orch)/F.M.Fontaine: Concertino, DGG 100131 A 8 Fantasie symphonique (orch) - cond.Baily S 9 Balanchivadze: Pno Con 4 - Tcherkasov, USSR RTVSO, cond.Provatorov , (plain MELODIYA C10. 9671 A 25 Melodiya jacket) S 10 Banks, Don: Vln Con (Dommett, cond.P.Thomas)/ M.Williamson: The Display WORLD RECO S 5264 A 8 (cond.Hopkins) S 11 Bantock: Pierrot Ov/ Bridge: Summer, Hamlet, Suite for String Orch/ Butterworth: -

Shostakovich (1906-1975)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Born in St. Petersburg. He entered the Petrograd Conservatory at age 13 and studied piano with Leonid Nikolayev and composition with Maximilian Steinberg. His graduation piece, the Symphony No. 1, gave him immediate fame and from there he went on to become the greatest composer during the Soviet Era of Russian history despite serious problems with the political and cultural authorities. He also concertized as a pianist and taught at the Moscow Conservatory. He was a prolific composer whose compositions covered almost all genres from operas, ballets and film scores to works for solo instruments and voice. Symphony No. 1 in F minor, Op. 10 (1923-5) Yuri Ahronovich/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Overture on Russian and Kirghiz Folk Themes) MELODIYA SM 02581-2/MELODIYA ANGEL SR-40192 (1972) (LP) Karel Ancerl/Czech Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Symphony No. 5) SUPRAPHON ANCERL EDITION SU 36992 (2005) (original LP release: SUPRAPHON SUAST 50576) (1964) Vladimir Ashkenazy/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15, Festive Overture, October, The Song of the Forest, 5 Fragments, Funeral-Triumphal Prelude, Novorossiisk Chimes: Excerpts and Chamber Symphony, Op. 110a) DECCA 4758748-2 (12 CDs) (2007) (original CD release: DECCA 425609-2) (1990) Rudolf Barshai/Cologne West German Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1994) ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 6324 (11 CDs) (2003) Rudolf Barshai/Vancouver Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphony No. -

Download Booklet

552129-30bk VBO Shostakovich 10/2/06 4:51 PM Page 8 CD1 1 Festive Overture in A, Op. 96 . 5:59 2 String Quartet No. 8 in C minor, Op. 110 III. Allegretto . 4:10 3 Piano Trio No. 2 in E minor, Op. 67 III. Largo . 5:35 4 Cello Concerto No. 1 in E flat, Op. 107 I. Allegretto . 6:15 5–6 24 Preludes and Fugues – piano, Op.87 Prelude and Fugue No. 1 in C major . 6:50 7 Symphony No. 5 in D minor, Op. 47 II. Allegretto . 5:08 8 Cello Sonata, Op. 40 IV. Allegro . 4:30 9 The Golden Age: Ballet Suite, Op. 22a Polka . 1:52 0 String Quartet No. 3 in F, Op. 73 IV. Adagio . 5:27 ! Symphony No. 9 in E flat, Op. 54 III. Presto . 2:48 @ 24 Preludes – piano, Op. 34 Prelude No. 10 in C sharp minor . 2:06 # Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 77 IV. Burlesque . 5:02 $ The Gadfly Suite, Op. 97a Romance . 5:52 % Symphony No. 10 in E minor, Op. 93 II. Allegro . 4:18 Total Timing . 66:43 CD2 1 Jazz Suite No. 2 VI. Waltz 2 . 3:15 2 Piano Concerto No. 1 in C minor, Op. 35 II. Lento . 8:31 3 Symphony No. 7 in C, Op. 60, ‘Leningrad’ II. Moderato . 11:20 4 3 Fantastic Dances, Op. 5 Polka . 1:07 5 Symphony No. 13 in B flat minor, Op. 113, ‘Babi Yar’ II. Humour . 7:36 6 Piano Quintet, Op. 57 III.Scherzo . -

The Man Who Found the Nose'

SPECIAL INTERVIEW The Man who found The Nose’ An Interview with Gennady Nikolayevich Rozhdestvensky By Alan Mercer Born in Moscow on 4 May 1931, (1974-1977 and 1992-1995), and Rozhdestvensky grew up with his the Vienna Symphony (1980-1982). spritely 85 years of age at conductor father Nikolai Anosov Also in the 1970s, Rozhdestvensky the time of our encounter at (1900-1962) and his singer mother worked as music director and con the Paris-based Shostakovich Natalia Rozhdestvenskaya (1900- ductor of the Moscow Chamber ACentre, Gennady Rozhdestvensky’s1997). After graduating from the Music Theatre, where together with demeanour has barely changed from Central Music School at the Mos director Boris Pokrovsky he revived that of the 1960s, when Western con- cow Conservatory as a pianist in Shostakovich’s 1920s opera The Nose. cert-goers were first treated to his the class of L.N. Oborin, he began Rozhdestvensky has focused individualistic podium style, not to studying what was to become his much of his career on music of mention his highly affable manner career vocation under the guidance the twentieth century, including with audiences and orchestras alike. of his father. In 1951, he trained at premieres of works by Shchedrin, As one of the few remaining artists the Bolshoi Theatre, and went on to Slonimsky, Eshpai, Tishchenko, to have worked closely with the 20th work at the famous venue at vari Kancheli, Schnittke, Gubaidulina, century’s music elite—Shostakovich ous periods between 1951 and 2001, and Denisov. included—the conductor’s career is when he became the establishment’s Prior to our conversation, the imbibed with both the traditions General Artistic Director. -

ALC 3143 WEB BOOKLET.Indd

The audience listened with enthusiasm and the scherzo had to be repeated. At the end, Mitya was hurt when Shostakovich commented that he had been hindered in composing when he was [Dmitri] was called up to the stage over and over again. When our handsome young composer a student. The dramatic final bars of Maximilian Steinberg’s own powerful Second Symphony of appeared, looking still like a boy, the enthusiasm turned into one long thunderous ovation. He came 1909 (in memory of Rimsky-Korsakov), in its use of the orchestral piano, during the redemptive, to take his bows, sometimes with Malko [Nikolai Malko, the conductor], sometimes alone’ though paradoxically doom-laden coda, to some extent anticipate the music of his young pupil. (Shostakovich’s mother - letter to a friend after the first performance of Symphony No.1, performed by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra on 12th May, 1926) No composer works in a vacuum and despite its remarkable originality Shostakovich’s First Symphony The slow movement ... shows us an imagination and a degree of compassion that go far beyond does show the influences of other composers, not least Stravinsky, whose ballet score Petrushka youthful insight…What is important is that it [the Symphony] communicates a vital spiritual (1909-11) shares some of the ironic, grotesque humour of the first two movements of the Shostakovich experience. (Robert Layton ‘The Symphony – Elgar to the Present Day’, Penguin, 1967) symphony - a habitual feature of the composer’s music, not least in the opening movement of his final symphony – No.15 of 1971. Prokofiev, Tchaikovsky, Mahler, Scriabin and Bruckner have also Symphony No.1 in F minor, Op.10 (1924-5) which was completed as a graduation exercise, when been identified as possible influences. -

Dmitry Shostakovich's <I>Twenty-Four Preludes and Fugues</I> Op. 87

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music Music, School of Spring 4-23-2010 Dmitry Shostakovich's Twenty-Four Preludes and Fugues op. 87: An Analysis and Critical Evaluation of the Printed Edition Based on the Composer's Recorded Performance Denis V. Plutalov University of Nebraska at Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Composition Commons Plutalov, Denis V., "Dmitry Shostakovich's Twenty-Four Preludes and Fugues op. 87: An Analysis and Critical Evaluation of the Printed Edition Based on the Composer's Recorded Performance" (2010). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 27. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. DMITRY SHOSTAKOVICH'S TWENTY-FOUR PRELUDES AND FUGUES, OP. 87: AN ANALYSIS AND CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE PRINTED EDITION BASED ON THE COMPOSER'S RECORDED PERFORMANCE by Denis V. Plutalov A Doctoral Document Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music Under the Supervision of Professor Mark Clinton Lincoln, Nebraska May 2010 Dmitry Shostakovich's Twenty-Four Preludes and Fugues op. 87: An Analysis and Critical Evaluation of the Printed Edition Based on the Composer's Recorded Performance Denis Plutalov, D. -

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Born September 25, 1906 in St

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Born September 25, 1906 in St. Petersburg; died August 9, 1975 in Moscow. Symphony No. 5, Opus 47 (1937) PREMIERE OF WORK: Leningrad, November 21, 1937 Great Hall of the Leningrad Philharmonic Leningrad Philharmonic Yevgeny Mravinsky, conductor APPROXIMATE DURATION: 52 minutes INSTRUMENTATION: piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, E-flat and two B-flat clarinets, two bassoons, contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion, two harps, celesta, piano and strings “COMPOSER REGAINS HIS PLACE IN SOVIET,” read a headline of The New York Times on November 22, 1937. “Dmitri Shostakovich, who fell from grace two years ago, on the way to rehabilitation. His new symphony hailed. Audience cheers as Leningrad Philharmonic presents work.” The background of Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony is well known. His career began before he was twenty with the cheeky First Symphony; he was immediately acclaimed the brightest star in the Soviet musical firmament. In the years that followed, he produced music with amazing celerity, and even managed to catch Stalin’s attention, especially with his film scores. (Stalin was convinced that film was one of the most powerful weapons in his propaganda arsenal.) The mid-1930s, however, the years during which Stalin tightened his iron grip on Russia, saw a repression of the artistic freedom of Shostakovich’s early years, and some of his newer works were assailed with the damning criticism of “formalism.” The opera The Nose, the ballets The Golden Age and The Bolt and even the blatantly jingoistic Second and Third Symphonies were the main targets. The storm broke in an article in Pravda on January 28, 1936 entitled “Muddle Instead of Music.” The “muddle” was the opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, a lurid tale of adultery and murder in the provinces that is one of Shostakovich’s most powerful creations. -

4932 Appendices Only for Online.Indd

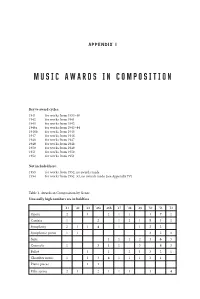

APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Key to award cycles: 1941 for works from 1934–40 1942 for works from 1941 1943 for works from 1942 1946a for works from 1943–44 1946b for works from 1945 1947 for works from 1946 1948 for works from 1947 1949 for works from 1948 1950 for works from 1949 1951 for works from 1950 1952 for works from 1951 Not included here: 1953 for works from 1952, no awards made 1954 for works from 1952–53, no awards made (see Appendix IV) Table 1. Awards in Composition by Genre Unusually high numbers are in boldface ’41 ’42 ’43 ’46a ’46b ’47 ’48 ’49 ’50 ’51 ’52 Opera2121117 2 Cantata 1 2 1 2 1 5 32 Symphony 2 1 1 4 1122 Symphonic poem 1 1 3 2 3 Suite 111216 3 Concerto 1 3 1 1 3 4 3 Ballet 1 1 21321 Chamber music 1 1 3 4 11131 Piano pieces 1 1 Film scores 21 2111 1 4 APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Songs 2121121 6 3 Art songs 1 2 Marches 1 Incidental music 1 Folk instruments 111 Table 2. Composers in Alphabetical Order Surnames are given in the most common transliteration (e.g. as in Wikipedia); first names are mostly given in the familiar anglicized form. Name Alternative Spellings/ Dates Class and Year Notes Transliterations of Awards 1. Afanasyev, Leonid 1921–1995 III, 1952 2. Aleksandrov, 1883–1946 I, 1942 see performers list Alexander for a further award (Appendix II) 3. Aleksandrov, 1888–1982 II, 1951 Anatoly 4. -

Parola Scenica: Towards Realism in Italian Opera Etdhendrik Johannes Paulus Du Plessis

Parola Scenica: Towards Realism in Italian Opera ETDHendrik Johannes Paulus du Plessis A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD by Thesis Abstract This thesis attempts to describe the emergence of a realistic writing style in nine- teenth-century Italian opera of which Giuseppe Verdi was the primary architect. Frequently reinforced by a realistic musico-linguistic device that Verdi would call parola scenica, the object of this realism is a musical syntax in which nei- ther the dramatic intent of the text nor the purely musical intent overwhelms the other. For Verdi the dramatically effective depiction of a ‘slice of a particular life’—a realist theatrical notion—is more important than the mere mimetic description of the words in musical terms—a romantic theatrical notion in line with opera seria. Besides studying the device of parola scenica in Verdi’s work, I also attempt to cast light on its impact on the output of his peers and successors. Likewise, this study investigates how the device, by definition texted, impacts on the orchestra as a means of realist narrative. My work is directed at explaining how these changes in mood of thought were instrumental in effecting the gradual replacement of the bel canto singing style typical of the opera seria of Rossini, Donizetti, and Bellini, by the school of thought of verismo, as exemplified by Verdi’s experiments. Besides the work of Verdi and the early nineteenth-cen- tury Italian operatic Romanticists, I touch also briefly on the œuvres of Puccini, ETDGiordano and the other veristi. -

Prokofiev, Sergey (Sergeyevich)

Prokofiev, Sergey (Sergeyevich) (b Sontsovka, Bakhmutsk region, Yekaterinoslav district, Ukraine, 11/23 April 1891; d Moscow, 5 March 1953). Russian composer and pianist. He began his career as a composer while still a student, and so had a deep investment in Russian Romantic traditions – even if he was pushing those traditions to a point of exacerbation and caricature – before he began to encounter, and contribute to, various kinds of modernism in the second decade of the new century. Like many artists, he left his country directly after the October Revolution; he was the only composer to return, nearly 20 years later. His inner traditionalism, coupled with the neo-classicism he had helped invent, now made it possible for him to play a leading role in Soviet culture, to whose demands for political engagement, utility and simplicity he responded with prodigious creative energy. In his last years, however, official encouragement turned into persecution, and his musical voice understandably faltered. 1. Russia, 1891–1918. 2. USA, 1918–22. 3. Europe, 1922–36. 4. The USSR, 1936–53. WORKS BIBLIOGRAPHY DOROTHEA REDEPENNING © Oxford University Press 2005 How to cite Grove Music Online 1. Russia, 1891–1918. (i) Childhood and early works. (ii) Conservatory studies and first public appearances. (iii) The path to emigration. © Oxford University Press 2005 How to cite Grove Music Online Prokofiev, Sergey, §1: Russia: 1891–1918 (i) Childhood and early works. Prokofiev grew up in comfortable circumstances. His father Sergey Alekseyevich Prokofiev was an agronomist and managed the estate of Sontsovka, where he had gone to live in 1878 with his wife Mariya Zitkova, a well-educated woman with a feeling for the arts. -

Kabalevsky Was Born in St Petersburg on 30 December 1904 and Died in Moscow on 14 February 1987 at the Age of 83

DMITRI KABALEVSKY SIKORSKI MUSIKVERLAGE HAMBURG SIK 4/5654 2 CONTENTS FOREWORD by Maria Kabalevskaya ...................... 4 VORWORT ....................................... 6 INTRODUCTION by Tatjana Frumkis .................... 8 EINFÜHRUNG .................................. 10 AWARDS AND PRIZES ............................ 13 CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF WORKS .............. 15 SYSTEMATIC INDEX OF WORKS Stage Works ..................................... 114 Orchestral Works ................................. 114 Instrumental Soloist and Orchestra .................... 114 Wind Orchestra ................................... 114 Solo Voice(s) and Orchestra ......................... 115 Solo Voice(s), Choir and Orchestra .................... 115 Choir and Orchestra ............................... 115 Solo Voice(s), Choir and Piano ....................... 115 Choir and Piano .................................. 115 Voice(s) a cappella ................................ 117 Voice(s) and Instruments ............................ 117 Voice and Piano .................................. 117 Piano Solo ....................................... 118 Piano Four Hands ................................. 119 Instrumental Chamber Works ........................ 119 Incidental Music .................................. 120 Film Music ...................................... 120 Arrangements .................................... 121 INDEX Index of Opus Numbers ............................ 122 Works Without Opus Numbers ....................... 125 Alphabetic Index of Works .........................