National Fiscal Policy in Papua New Guinea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papua New Guinea

PAPUA NEW GUINEA INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION NEWSLETTER: Apr—Jun 2020 Members of Kumin community constructing their Community Hall supported by IOM through the UN Highlights Peace Building Fund in Southern Highlands Province. © Peter Murorera/ IOM 2020 ◼ IOM strengthened emergency ◼ IOM reinforced peacebuilding ◼ IOM supported COVID-19 Risk preparedness in Milne Bay and efforts of women, men and youth Communication and Community Hela Provinces through training from conflict affected communities Engagement activities in East Sepik, disaster management actors on through training in Community East New Britain, West New Britain, use of the Displacement Tracking Peace for Development Planning Morobe, Oro, Jiwaka, Milne Bay, Matrix. and provision of material support in Madang, and Western Provinces. Southern Highlands Province. New Guinea (PNG) Fire Service, PNG Defense Force, DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX police, churches, local community representatives and Recognizing Milne Bay and Hela Provinces’ vulnerabilities volunteers, private sector and the United Nations (UN). to natural and human-induced hazards such as flooding Participants were trained and upskilled on data and tribal conflict that lead to population displacement, gathering, data management and analysis to track IOM through funding from USAID delivered Displacement population displacement and inform targeted responses. Tracking Matrix (DTM) trainings to 73 participants (56 men and 17 women) from the two Provinces. IOM’s DTM was initially utilized in Milne Bay following a fire in 2018 and in Hela following the M7.5 earthquake The trainings on the DTM information gathering tool, that struck the Highlands in February that same year. The held in Milne Bay (3-5 June 2020) and Hela (17-19 June DTM recorded critical data on persons displaced across 2020) attracted participants from the Government the provinces that was used for the targeting of (Provincial, District and Local Level), Community-Based humanitarian assistance. -

Papua New Guinea (And Comparators)

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized BELOW THE GLASS FLOOR Analytical Review of Expenditure by Provincial Administrations on Rural Health from Health Function Grants & Provincial Internal Revenue JULY 2013 Below the Glass Floor: An Analytical Review of Provincial Administrations’ Rural Health Expenditure Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone: 978-750- 8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street, NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax 202-522-2422; email: [email protected]. - i - Below the Glass Floor: An Analytical Review of Provincial Administrations’ Rural Health Expenditure Table of Contents Acknowledgment ......................................................................................................................... 5 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................. -

Operational Highlights 2018

NEWSLETTER PAPUA NEW GUINEA OPERATIONAL HIGHLIGHTS 2018 JANUARY - DECEMBER 2018 The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is an impartial, neutral and independent humanitarian organization that was founded in 1863 to help people affected by armed conflict or other violence. We have been working in Papua New Guinea (PNG) since 2007 as part of the regional delegation in the Pacific based in Suva, Fiji. Our mandate is to do everything we can to protect the dignity of people and relieve their suffering. We also seek to prevent hardship by promoting and strengthening humanitarian law and championing universal humanitarian principles. The PNG Red Cross Society (PNGRCS) is a close partner in our efforts. Here’s a snap shot of our activities in 2018: PROTECTING VULNERABLE PEOPLE The ICRC visits places of detention in correctional institutions and police lock-ups to monitor the living condition and treatment of detainees. Our reports and findings from the visits are treated as confidential and shared only with the authorities concerned and recommendations are implemented with their support. The ICRC also assists authorities with distribution of hygiene material, recreational items and medical equipment. Projects on water and sanitation are also implemented in many facilities. In 2018, we: • Visited 15 places of detention in areas of operations in PNG. • Provided recreational items, hygiene kits and blankets to police lock-ups and correctional institutions. • Facilitated correctional services officers to attend two training programmes abroad and helped a medical doctor participate in a health-in-detention training in Bangkok and Cambodia. • Facilitated first-aid training of correctional services staff in coordination with PNGRCS. -

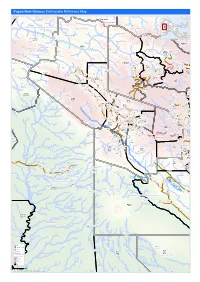

Earthquake Reference Map

Papua New Guinea: Earthquake Reference Map Telefomin London Rural Lybia Telefomin Tunap/Hustein District Ambunti/Drekikier District Kaskare Akiapjmin WEST SEPIK (SANDAUN) PROVINCE Karawari Angoram EAST SEPIK PROVINCE Rural District Monduban HELA PROVINCE Wundu Yatoam Airstrip Lembana Kulupu Malaumanda Kasakali Paflin Koroba/Kopiago Kotkot Sisamin Pai District Emo Airstrip Biak Pokale Oksapmin Liawep Wabag Malandu Rural Wayalima District Hewa Airstrip Maramuni Kuiva Pauteke Mitiganap Teranap Lake Tokom Rural Betianap Puali Kopiago Semeti Oksapmin Sub Aipaka Yoliape Waulup Oksapmin District ekap Airport Rural Kenalipa Seremty Divanap Ranimap Kusanap Tomianap Papake Lagaip/Pogera Tekin Winjaka Airport Gawa Eyaka Airstrip Wane 2 District Waili/Waki Kweptanap Gaua Maip Wobagen Wane 1 Airstrip aburap Muritaka Yalum Bak Rural imin Airstrip Duban Yumonda Yokona Tili Kuli Balia Kariapuka Yakatone Yeim Umanap Wiski Aid Post Poreak Sungtem Walya Agali Ipate Airstrip Piawe Wangialo Bealo Paiela/Hewa Tombaip Kulipanda Waimalama Pimaka Ipalopa Tokos Ipalopa Lambusilama Rural Primary Tombena Waiyonga Waimalama Taipoko School Tumundane Komanga ANDS HIG PHaLin Yambali Kolombi Porgera Yambuli Kakuane C/Mission Paiela Aspiringa Maip Pokolip Torenam ALUNI Muritaka Airport Tagoba Primary Kopetes Yagoane Aiyukuni SDA Mission Kopiago Paitenges Haku KOPIAGO STATION Rural Lesai Pali Airport School Yakimak Apostolic Mission Politika Tamakale Koemale Kambe Piri Tarane Pirika Takuup Dilini Ingilep Kiya Tipinini Koemale Ayene Sindawna Taronga Kasap Luth. Yaparep -

Integrated Land Management, Restoration of Degraded Landscapes and Natural Capital Assessment in the Mountains of Papua New Guinea

5/7/2020 WbgGefportal Project Identification Form (PIF) entry – Full Sized Project – GEF - 7 Integrated land management, restoration of degraded landscapes and natural capital assessment in the mountains of Papua New Guinea Part I: Project Information GEF ID 10580 Project Type FSP Type of Trust Fund GET CBIT/NGI CBIT NGI Project Title Integrated land management, restoration of degraded landscapes and natural capital assessment in the mountains of Papua New Guinea Countries Papua New Guinea Agency(ies) UNEP Other Executing Partner(s) Executing Partner Type Conservation and Environment Protection Authority (CEPA) Government https://gefportal.worldbank.org 1/61 5/7/2020 WbgGefportal GEF Focal Area Multi Focal Area Taxonomy Focal Areas, Land Degradation Neutrality, Land Degradation, Land Cover and Land cover change, Carbon stocks above or below ground, Land Productivity, Biodiversity, Mainstreaming, Extractive Industries, Forestry - Including HCVF and REDD+, Agriculture and agrobiodiversity, Financial and Accounting, Payment for Ecosystem Services, Natural Capital Assessment and Accounting, Species, Threatened Species, Influencing models, Transform policy and regulatory environments, Strengthen institutional capacity and decision-making, Demonstrate innovative approache, Stakeholders, Private Sector, Individuals/Entrepreneurs, SMEs, Beneficiaries, Civil Society, Non-Governmental Organization, Community Based Organization, Local Communities, Communications, Awareness Raising, Education, Public Campaigns, Type of Engagement, Partnership, Information -

An Ethnography of Change in Papua New Guinea

NAVIGATING THE FUTURE An Ethnography of Change in Papua New Guinea NAVIGATING THE FUTURE An Ethnography of Change in Papua New Guinea MONICA MINNEGAL AND PETER D. DWYER ASIA-PACIFIC ENVIRONMENT MONOGRAPH 11 Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Minnegal, Monica, author. Title: Navigating the future : an ethnography of change in Papua New Guinea / Monica Minnegal ; Peter D. Dwyer. ISBN: 9781760461232 (paperback) 9781760461249 (ebook) Series: Asia-pacific environment monographs ; 11 Subjects: Liquefied natural gas industry--Social aspects--Papua New Guinea. Ethnology--Papua New Guinea. Kubo (Papua New Guinean people)--Economic conditions. Kubo (Papua New Guinean people)--Social conditions. Papuans--Papua New Guinea--Attitudes. Other Creators/Contributors: Dwyer, Peter D., 1937- author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: ‘Entrance to Owabi Corner’ by Peter D. Dwyer, Suabi, 2014. This edition © 2017 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements ..................................................vii Caveats .............................................................ix Tables ..............................................................xiii -

Papua New Guinea Mvam Food Security & Livelihoods Monitoring System

Fighting Hunger Worldwide Papua New Guinea mVAM Food Security & Livelihoods Monitoring System Report 3 | July 2017 World Food ProducedProgramme by WFP | Department in support of of National Agriculture Disaster and Centre, Livestock Department | National of Agriculture Disaster and Centre Livestock and the Government of Papua 1 New Guinea Contacts and Information This Papua New Guinea Food Security & Livelihoods Monitoring System Report is jointly produced by the Department of Agriculture and Livestock, the National Disaster Centre, and the United Nations World Food Programme. For further information, contact: Department of Agriculture and Livestock National Disaster Centre United Nations World Food Programme Brown Konabe Martin Mose Venkat Dheeravath Director, Food Security Branch Acting Director Programme Policy Officer, Head of Office Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Mobile: +675 71691483 Mobile: +675 76289180 Mobile: +675 70723345 Papua New Guinea Food Security & Livelihoods Monitoring System, July 2017 KEY MESSAGES Between 25 April and 26 June 2017 the World Food Programme (WFP), in support of the Department of Agriculture and Livestock (DAL) and the National Disaster Centre (NDC), conducted a mobile survey to establish a baseline for the food security and livelihood monitoring system in Papua New Guinea. The survey was carried out in 326 LLGs (Local Level Government) and a total of 4,490 respondents were interviewed by phone from the Digicel call centre in Port Moresby. The food security status of households as measured during the April-June 2017 survey continues to improve as compared to the situation in early 2016. -

Papua New Guinea

© UNICEF/PNG/2018/Ramly Papua New Guinea Humanitarian Situation Report No. 6 Mid-Year Report 01 January through 31 July 2018 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights • During the first half of 2018, the humanitarian situation in Papua New 01 January – 31 July 2018 Guinea (PNG) deteriorated and remains grim due to three States of Emergency in PNG: Earthquake disaster for 4 provinces; Peace and 544,000 people affected Security for Southern Highlands; Public Health emergency due to polio earthquakes, including 252,480 outbreak. children • UNICEF's has reached over 37,000 children with measles and rubella vaccinations, 23,000 children with micronutrient powder; 64,000 270,000 people need immediate people have been given access to safe drinking water. life-saving assistance, including • UNICEF is supporting the Government to respond to the polio 125,000 children outbreak. UNICEF is procuring over a million oral polio vaccines. In the first of four vaccination rounds, some 306,000 children have been Funding requirement for 2018 as vaccinated. part of the regional humanitarian • Close to 400 child protection duty bearers, nurses, vaccinators, appeal: US$13.7 million. nutrition workers and other community health workers, teachers all trained on disaster recovery measures and back at work Funds received: US$3.64 million • UNICEF has procured and managed 118.79 metric tons or 481.65 cubic meters of emergency education, health, nutrition, protection, water, Funding Status 2018 and sanitation supplies for direct delivery, delivery through partners or as government-controlled supplies. The total value of procurement for emergency supplies and related services is over US$ 822,000. -

Papua New Guinea Contents

ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT | 2018 UNITED NATIONS IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA CONTENTS United Nations Resident Coordinator’s Foreword 1 Development Trends 2 Coordination Results of Delivering as One United Nations System 5 One Programme 5 Budgetary Framework and the PNG United Nations Innovating for Results (People, Prosperity Country Fund 6 and Planet) 22 Communicating as One 6 Striving for Gender Equity (People, Prosperity and Planet) 23 Operating as One/One United Nations Haus 6 Environment, Climate Change, Disaster Risk 2018 Overview 8 Reduction (Planet) 24 SDG Snapshot 11 Building and Maintaining Peace and Security Medium-Term Development Plan III and Effective Humanitarian Coordination (Peace) 26 Linkages Snapshot 12 Preventing and Sustaining Peace 26 Effective Partnerships and Collaborations 28 Highlights of the 2018 Programmatic Results 15 Adopting New Approaches 28 Promoting Sustained Economic Growth and Sustainable Development 15 Women, Peace and Security 28 Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Youth, Peace and Security 29 Sustainable Development (Prosperity) 15 Strengthening National and Sustainable Economic Growth (Prosperity) 19 Intergovernmental Processes 29 Partnerships (People, Prosperity and Planet) 21 Promoting and Protecting Human Rights 31 Financing for Sustainable Development Summary of Progress Against UNDAF Indicators 33 (People, Prosperity and Planet) 22 Delivering as One Risk Monitoring and Lessons Learned 34 The PNG UN Country Fund 37 Overview 37 Financial Performance 39 Accountability and Transparency 45 PAPUA NEW GUINEA UNITED NATIONS RESIDENT Development Trends COORDINATOR’S FOREWARD Papua New Guinea is one of the world’s efforts. The impact on rural and remote communities It is with great pleasure that I present the Government with strengthening its national systems and was particularly significant. -

PNG Highlands Joint Programme 2020-2022

PNG Highlands Joint Programme 2020-2022 Converging Toward Peace & Development Country: Papua New Guinea Geographic focus: The provinces of Hela and Southern Highlands in Papua New Guinea (henceforth referred to as “Highlands”.) Title: PNG Highlands Joint Programme for Peace and Development (“Highlands Joint Programme”/HJP) Outcomes: By 2022: • Communities affected by conflict in the Highlands have increased capacity to promote and demand for peace and social cohesion • Highlands’ communities and households have improved resilience to manage risks and mitigate shocks from conflict and man-made/natural disasters • Traditional/non-traditional leaders and service providers have enhanced knowledge and skills to integrate peacebuilding and human rights strategies into service delivery in conflict affected areas in the highlands • Public institutions in the Highlands have people-centred, proactive and transparent/accountable systems to support effective leadership that promotes peace, security and human rights Duration: 3 years Total estimated US$30 million budget* Anticipated Jan 2020 to Dec 2022 Out of which: start/end dates: 1. Funded Budget US$6.2million Fund Management Pass-Through and Parallel 2. Unfunded budget US$23.8million Options: Administrative Multi-Partner Trust Fund * Total estimated budget includes both programme costs Agent: Office and indirect support costs Sources of funded Government of PNG budget: European Union USAID FAO UNICEF UNDP UN Peacebuilding Fund United Nations National Coordinating Authorities (signature/date) -

Hela Province

TN34 Highlands Earthquake Disaster Social Infrastructure Assessment Report – Hela Province Prepared for the Australian High Commission 16 April 2018 This program, administered by Cardno, is an Australian aid project, funded by the Australian Government Contact Information Technical Enabling Unit Third Floor, Kina Haus Douglas Street Port Moresby, PNG Document History Description of Version Effective Date Prepared by Reviewed by Revision v0 16 April 2018 Draft for Review Bruce P, Roger Bottrall Cathy A, Jayson A © Cardno. Copyright in the whole and every part of this document belongs to Cardno and may not be used, sold, transferred, copied or reproduced in whole or in part in any manner or form or in or on any media to any person other than by agreement with Cardno. This document is produced by Cardno solely for the benefit and use by the client in accordance with the terms of the engagement. Cardno does not and shall not assume any responsibility or liability whatsoever to any third party arising out of any use or reliance by any third party on the content of this document. Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. 5 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 5 Assessment and Scoping Process ................................................................................................ 5 Recommended Allocations .......................................................................................................... -

Oro Province Education Vacancy Gazette 2018

DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION EDUCATION VACANCY GAZETTE 2018 Published by Authority VOLUME: 41, No. 01 WAIGANI, FRIDAY, 29th JUNE 2018 _______________________________________________________________________________________ ORO PROVINCE -- 1 -- C O N T E N T S Pages SECTION A: INTRODUCTION/PREAMBLE DEFINITION……………………………………………………………… 3 OPERATIONAL TIMETABLE 1 OF 2018……………………………… 6 CHURCH CODE AND PHILOSOPHIES……………………….……...... 7 CODE FOR SUBJECT AREAS…………………………………….……. 12 POSTAL ADDRESS (Selection & Appointing Authorities) ……………. 13 SECTION B: ADVERTISED TEACHING VACANCIES COMMUNITY AND PRIMARY SCHOOLS…………………………….. 14 HIGH SCHOOLS …………………………………………………………. 26 SECONDARY SCHOOLS AND VOCATIONAL CENTRES.....….…… 27 SECTION C: MISCELLANEOUS - ELIGIBILITY AWARDS ELIGIBILITY LISTS ……………………………………………………… 29 -- 2 -- PAPUA NEW GUINEA TEACHING SERVICE VACANCIES (TEACHING SERVICE ACT NO. 12 OF 1988) 1. DEFINITION 3.3 Auxiliary members and other overseas persons are eligible for appointment to vacancies in National 1.1 In this preamble – and Provincial Institutions. (a) “advertising authority” means the National 3.4 Contract officers cannot apply nor can they be Education Board (NEB) considered for appointment to vacancies in Church (b) “appointing authority” means the Provincial Agency schools because of certain terms and Education Board (PEB) and National conditions of their employment Education Board (NEB) for national Institutions. 3.5 Non-citizens outside PNG are not eligible to apply. (c) “auxiliary member” means a person (non- citizen) who has been admitted to auxiliary 4. WHO MUST APPLY membership of the Teaching Service. (d) “member of the Teaching Service” or Concurrent Occupant – is a teacher who is substantive “member” means a national including a to the level but is not the tenure holder of the position. naturalized citizen who is a full member, a The teacher may have tenure on the same level provisional member, or an associate member elsewhere.