Papua New Guinea Mvam Food Security & Livelihoods Monitoring System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FR-29-Kavieng.Pdf

Secretariat of the Pacific Community FIELD REPORT No. 29 on TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE ON SMALL-SCALE BAITFISHING TRIALS AND COURSE PRESENTATION TO THE NATIONAL FISHERIES COLLEGE, AND FAD EXPERIMENTS TO THE COMMUNITY FISHERIES MANAGEMENT DEVELOPMENT PROJECT ASSISTING IN KAVIENG, PAPUA NEW GUINEA 12 September to 7 December 2005 by William Sokimi Fisheries Development Officer Secretariat of the Pacific Community Noumea, New Caledonia 2006 © Copyright Secretariat of the Pacific Community 2006 All rights for commercial / for profit reproduction or translation, in any form, reserved. The SPC authorises the partial reproduction or translation of this material for scientific, educational or research purposes, provided the SPC and the source document are properly acknowledged. Permission to reproduce the document and/or translate in whole, in any form, whether for commercial / for profit or non-profit purposes, must be requested in writing. Original SPC artwork may not be altered or separately published without permission. This field report forms part of a series compiled by the Fisheries Development Section of the Secretariat of the Pacific Community’s Coastal Fisheries Programme. These reports have been produced as a record of individual project activities and country assignments, from materials held within the Section, with the aim of making this valuable information readily accessible. Each report in this series has been compiled within the Fisheries Development Section to a technical standard acceptable for release into the public arena. Secretariat -

Papua New Guinea

PAPUA NEW GUINEA EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS OPERATIONAL LOGISTICS CONTINGENCY PLAN PART 2 –EXISTING RESPONSE CAPACITY & OVERVIEW OF LOGISTICS SITUATION GLOBAL LOGISTICS CLUSTER – WFP FEBRUARY – MARCH 2011 1 | P a g e A. Summary A. SUMMARY 2 B. EXISTING RESPONSE CAPACITIES 4 C. LOGISTICS ACTORS 6 A. THE LOGISTICS COORDINATION GROUP 6 B. PAPUA NEW GUINEAN ACTORS 6 AT NATIONAL LEVEL 6 AT PROVINCIAL LEVEL 9 C. INTERNATIONAL COORDINATION BODIES 10 DMT 10 THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL 10 D. OVERVIEW OF LOGISTICS INFRASTRUCTURE, SERVICES & STOCKS 11 A. LOGISTICS INFRASTRUCTURES OF PNG 11 PORTS 11 AIRPORTS 14 ROADS 15 WATERWAYS 17 STORAGE 18 MILLING CAPACITIES 19 B. LOGISTICS SERVICES OF PNG 20 GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS 20 FUEL SUPPLY 20 TRANSPORTERS 21 HEAVY HANDLING AND POWER EQUIPMENT 21 POWER SUPPLY 21 TELECOMS 22 LOCAL SUPPLIES MARKETS 22 C. CUSTOMS CLEARANCE 23 IMPORT CLEARANCE PROCEDURES 23 TAX EXEMPTION PROCESS 24 THE IMPORTING PROCESS FOR EXEMPTIONS 25 D. REGULATORY DEPARTMENTS 26 CASA 26 DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH 26 NATIONAL INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGY AUTHORITY (NICTA) 27 2 | P a g e MARITIME AUTHORITIES 28 1. NATIONAL MARITIME SAFETY AUTHORITY 28 2. TECHNICAL DEPARTMENTS DEPENDING FROM THE NATIONAL PORT CORPORATION LTD 30 E. PNG GLOBAL LOGISTICS CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS 34 A. CHALLENGES AND SOLUTIONS PROPOSED 34 MAJOR PROBLEMS/BOTTLENECKS IDENTIFIED: 34 SOLUTIONS PROPOSED 34 B. EXISTING OPERATIONAL CORRIDORS IN PNG 35 MAIN ENTRY POINTS: 35 SECONDARY ENTRY POINTS: 35 EXISTING CORRIDORS: 36 LOGISTICS HUBS: 39 C. STORAGE: 41 CURRENT SITUATION: 41 PROPOSED LONG TERM SOLUTION 41 DURING EMERGENCIES 41 D. DELIVERIES: 41 3 | P a g e B. Existing response capacities Here under is an updated list of the main response capacities currently present in the country. -

Wanbel: Conflict, Reconciliation and Personhood Among the Sam People, Madang Province

Wanbel: Conflict, Reconciliation and Personhood among the Sam People, Madang Province David Eric Troolin Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Discipline of Anthropology, School of Social Sciences University of Adelaide May 2018 Contents Figures ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Declaration ................................................................................................................................. 8 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... 9 Glossary.................................................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 1: Wanbel among the Sam people ............................................................................... 16 A glimpse of wanbel ......................................................................................................... 16 The Sam people and the researcher ................................................................................ 17 Wanbel in Papua New Guinea ......................................................................................... 27 Problematising wanbel ................................................................................................... -

Health&Medicalinfoupdate8/10/2017 Page 1 HEALTH and MEDICAL

HEALTH AND MEDICAL INFORMATION The American Embassy assumes no responsibility for the professional ability or integrity of the persons, centers, or hospitals appearing on this list. The names of doctors are listed in alphabetical, specialty and regional order. The order in which this information appears has no other significance. Routine care is generally available from general practitioners or family practice professionals. Care from specialists is by referral only, which means you first visit the general practitioner before seeing the specialist. Most specialists have private offices (called “surgeries” or “clinic”), as well as consulting and treatment rooms located in Medical Centers attached to the main teaching hospitals. Residential areas are served by a large number of general practitioners who can take care of most general illnesses The U.S Government assumes no responsibility for payment of medical expenses for private individuals. The Social Security Medicare Program does not provide coverage for hospital or medical outside the U.S.A. For further information please see our information sheet entitled “Medical Information for American Traveling Abroad.” IMPORTANT EMERGENCY NUMBERS AMBULANCE/EMERGENCY SERVICES (National Capital District only) Police: 112 / (675) 324-4200 Fire: 110 St John Ambulance: 111 Life-line: 326-0011 / 326-1680 Mental Health Services: 301-3694 HIV/AIDS info: 323-6161 MEDEVAC Niugini Air Rescue Tel (675) 323-2033 Fax (675) 323-5244 Airport (675) 323-4700; A/H Mobile (675) 683-0305 Toll free: 0561293722468 - 24hrs Medevac Pacific Services: Tel (675) 323-5626; 325-6633 Mobile (675) 683-8767 PNG Wide Toll free: 1801 911 / 76835227 – 24hrs Health&MedicalInfoupdate8/10/2017 Page 1 AMR Air Ambulance 8001 South InterPort Blvd Ste. -

Health Situation Report 65 (Released: 22 March 2021; Report Period: 15 - 21 February 2021)

Papua New Guinea Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Health Situation Report #65 22 March 2021 Period of report: 15 - 21 March 2021 This Situation Report is jointly issued by PNG National Department of Health and World Health Organization once weekly. This Report is not comprehensive and covers information received as of reporting date. Situation Summary and Highlights ❒ As of 21 March 2021 (12:00 pm), there have been 3574 COVID-19 cases and 36 COVID-19 deaths reported in Papua New Guinea. From the period of 15 to 21 March, there were 1305 newly reported cases including 15 new deaths. This is the seventh consecutive week of increasing cases, and more than double the previous highest number of cases reported in a single week in PNG. ❒ The total number of provinces that have reported COVID-19 cases to date is twenty. Only Manus and Oro (Northern) Provinces have not reported cases to date. ❒ Public Health Unit at Doherty Institute in Australia has conducted whole genome sequencing on positive test samples sent from PNG and no variants of concern have been identified in sequencing conducted to date. ❒ The COVID-19 Hotline has experienced a 33.83% increase in calls since the last fortnight and the rate of health-related calls being referred to the Rapid Response Teams and PHAs has also increased by 33% from the prior week. ❒ This week the Australian government will deploy an Australian Medical Assistance Team (AUSMAT) to undertake assessments and Please note: Due to data cleaning, the number of critical planning for a potential full deployment cases may not add up exactly from last week. -

Papua New Guinea

PAPUA NEW GUINEA INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION NEWSLETTER: Apr—Jun 2020 Members of Kumin community constructing their Community Hall supported by IOM through the UN Highlights Peace Building Fund in Southern Highlands Province. © Peter Murorera/ IOM 2020 ◼ IOM strengthened emergency ◼ IOM reinforced peacebuilding ◼ IOM supported COVID-19 Risk preparedness in Milne Bay and efforts of women, men and youth Communication and Community Hela Provinces through training from conflict affected communities Engagement activities in East Sepik, disaster management actors on through training in Community East New Britain, West New Britain, use of the Displacement Tracking Peace for Development Planning Morobe, Oro, Jiwaka, Milne Bay, Matrix. and provision of material support in Madang, and Western Provinces. Southern Highlands Province. New Guinea (PNG) Fire Service, PNG Defense Force, DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX police, churches, local community representatives and Recognizing Milne Bay and Hela Provinces’ vulnerabilities volunteers, private sector and the United Nations (UN). to natural and human-induced hazards such as flooding Participants were trained and upskilled on data and tribal conflict that lead to population displacement, gathering, data management and analysis to track IOM through funding from USAID delivered Displacement population displacement and inform targeted responses. Tracking Matrix (DTM) trainings to 73 participants (56 men and 17 women) from the two Provinces. IOM’s DTM was initially utilized in Milne Bay following a fire in 2018 and in Hela following the M7.5 earthquake The trainings on the DTM information gathering tool, that struck the Highlands in February that same year. The held in Milne Bay (3-5 June 2020) and Hela (17-19 June DTM recorded critical data on persons displaced across 2020) attracted participants from the Government the provinces that was used for the targeting of (Provincial, District and Local Level), Community-Based humanitarian assistance. -

Papua New Guinea (And Comparators)

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized BELOW THE GLASS FLOOR Analytical Review of Expenditure by Provincial Administrations on Rural Health from Health Function Grants & Provincial Internal Revenue JULY 2013 Below the Glass Floor: An Analytical Review of Provincial Administrations’ Rural Health Expenditure Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone: 978-750- 8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street, NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax 202-522-2422; email: [email protected]. - i - Below the Glass Floor: An Analytical Review of Provincial Administrations’ Rural Health Expenditure Table of Contents Acknowledgment ......................................................................................................................... 5 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................. -

RAPID ASSESSMENT of AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS and DIABETIC RETINOPATHY REPORT Papua New Guinea 2017

RAPID ASSESSMENT OF AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS AND DIABETIC RETINOPATHY REPORT Papua New Guinea 2017 RAPID ASSESSMENT OF AVOIDABLE BLINDNESS AND DIABETIC RETINOPATHY PAPUA NEW GUINEA, 2017 1 Acknowledgements The Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness (RAAB) + Diabetic Retinopathy (DR) was a Brien Holden Vision Institute (the Institute) project, conducted in cooperation with the Institute’s partner in Papua New Guinea (PNG) – PNG Eye Care. We would like to sincerely thank the Fred Hollows Foundation, Australia for providing project funding, PNG Eye Care for managing the field work logistics, Fred Hollows New Zealand for providing expertise to the steering committee, Dr Hans Limburg and Dr Ana Cama for providing the RAAB training. We also wish to acknowledge the National Prevention of Blindness Committee in PNG and the following individuals for their tremendous contributions: Dr Jambi Garap – President of National Prevention of Blindness Committee PNG, Board President of PNG Eye Care Dr Simon Melengas – Chief Ophthalmologist PNG Dr Geoffrey Wabulembo - Paediatric ophthalmologist, University of PNG and CBM Mr Samuel Koim – General Manager, PNG Eye Care Dr Georgia Guldan – Professor of Public Health, Acting Head of Division of Public Health, School of Medical and Health Services, University of PNG Dr Apisai Kerek – Ophthalmologist, Port Moresby General Hospital Dr Robert Ko – Ophthalmologist, Port Moresby General Hospital Dr David Pahau – Ophthalmologist, Boram General Hospital Dr Waimbe Wahamu – Ophthalmologist, Mt Hagen Hospital Ms Theresa Gende -

Operational Highlights 2018

NEWSLETTER PAPUA NEW GUINEA OPERATIONAL HIGHLIGHTS 2018 JANUARY - DECEMBER 2018 The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is an impartial, neutral and independent humanitarian organization that was founded in 1863 to help people affected by armed conflict or other violence. We have been working in Papua New Guinea (PNG) since 2007 as part of the regional delegation in the Pacific based in Suva, Fiji. Our mandate is to do everything we can to protect the dignity of people and relieve their suffering. We also seek to prevent hardship by promoting and strengthening humanitarian law and championing universal humanitarian principles. The PNG Red Cross Society (PNGRCS) is a close partner in our efforts. Here’s a snap shot of our activities in 2018: PROTECTING VULNERABLE PEOPLE The ICRC visits places of detention in correctional institutions and police lock-ups to monitor the living condition and treatment of detainees. Our reports and findings from the visits are treated as confidential and shared only with the authorities concerned and recommendations are implemented with their support. The ICRC also assists authorities with distribution of hygiene material, recreational items and medical equipment. Projects on water and sanitation are also implemented in many facilities. In 2018, we: • Visited 15 places of detention in areas of operations in PNG. • Provided recreational items, hygiene kits and blankets to police lock-ups and correctional institutions. • Facilitated correctional services officers to attend two training programmes abroad and helped a medical doctor participate in a health-in-detention training in Bangkok and Cambodia. • Facilitated first-aid training of correctional services staff in coordination with PNGRCS. -

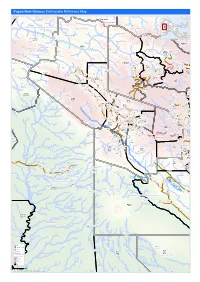

Earthquake Reference Map

Papua New Guinea: Earthquake Reference Map Telefomin London Rural Lybia Telefomin Tunap/Hustein District Ambunti/Drekikier District Kaskare Akiapjmin WEST SEPIK (SANDAUN) PROVINCE Karawari Angoram EAST SEPIK PROVINCE Rural District Monduban HELA PROVINCE Wundu Yatoam Airstrip Lembana Kulupu Malaumanda Kasakali Paflin Koroba/Kopiago Kotkot Sisamin Pai District Emo Airstrip Biak Pokale Oksapmin Liawep Wabag Malandu Rural Wayalima District Hewa Airstrip Maramuni Kuiva Pauteke Mitiganap Teranap Lake Tokom Rural Betianap Puali Kopiago Semeti Oksapmin Sub Aipaka Yoliape Waulup Oksapmin District ekap Airport Rural Kenalipa Seremty Divanap Ranimap Kusanap Tomianap Papake Lagaip/Pogera Tekin Winjaka Airport Gawa Eyaka Airstrip Wane 2 District Waili/Waki Kweptanap Gaua Maip Wobagen Wane 1 Airstrip aburap Muritaka Yalum Bak Rural imin Airstrip Duban Yumonda Yokona Tili Kuli Balia Kariapuka Yakatone Yeim Umanap Wiski Aid Post Poreak Sungtem Walya Agali Ipate Airstrip Piawe Wangialo Bealo Paiela/Hewa Tombaip Kulipanda Waimalama Pimaka Ipalopa Tokos Ipalopa Lambusilama Rural Primary Tombena Waiyonga Waimalama Taipoko School Tumundane Komanga ANDS HIG PHaLin Yambali Kolombi Porgera Yambuli Kakuane C/Mission Paiela Aspiringa Maip Pokolip Torenam ALUNI Muritaka Airport Tagoba Primary Kopetes Yagoane Aiyukuni SDA Mission Kopiago Paitenges Haku KOPIAGO STATION Rural Lesai Pali Airport School Yakimak Apostolic Mission Politika Tamakale Koemale Kambe Piri Tarane Pirika Takuup Dilini Ingilep Kiya Tipinini Koemale Ayene Sindawna Taronga Kasap Luth. Yaparep -

TCA Annusal Report 2018

Annual Report2018 CONSERVATION COMMUNITY CULTURE 1 Table Of Contents About Us About Us 3 Our People 4 Project Partners 6 About TCA Our Mission in PNG: Governance, Structure & Management 8 The Tenkile Conservation Alliance (TCA) was established in Papua New • Provide urgent and necessary services to rainforest communities Guinea (PNG) in 2001 and in Australia in 2016. The Tenkile is the local in Papua New Guinea that result in the relief of poverty and Message from the CEO 10 language name for the critically endangered Scott’s Tree Kangaroo which improve health. lives only in the Torricelli Mountain Range of Papua New Guinea (PNG). Message from the Chair 12 • Facilitate processes that provide opportunity for rainforest Our initial aim was to protect it from being hunted to extinction but now the communities in Papua New Guinea to govern, manage and protect Our Work 14 organisation has evolved into a holistic approach of integrated conservation their biological and cultural richness from exploitation. Objectives and Activities 15 and sustainable development program saving not just the Tenkile but the people as well. • Implement a bottom up approach to achieving all of TCA’s goals Conservation 19 and objectives. To ensure rainforest communities are enabled with Community 22 Our Vision: their own freedom of choice, as they advance into the 21st century, working towards self-determination of their communities. The vision of the TCA in both Australia and Papua New Guinea is: Culture 26 for the people of Papua New Guinea to value and protect their natural Financial Report 32 resources, communities and cultures in the context of advancing the overall Our Mission in Australia: well being of their communities and their places. -

Papua New Guinea: Featuring the Kenu & Kundu Festival

Papua New Guinea: Featuring the Kenu & Kundu Festival 11 Days Papua New Guinea: Featuring the Kenu & Kundu Festival Experience the energy of Papua New Guinea on this spectacular 11-day trip that includes the vibrant Kenu and Kundu Festival — one of the country's top cultural highlights! Once a year in November over 40 tribes paddle from their remote island homes to Alotau, where they gather to celebrate the region's drums and canoes. Hear the traditional beats of PNG as you witness canoe races, sing-sings, ritual exchanges, and vivid performances that combine ritual and revelry. This special departure also explores tropical Tufi and the scenic Western Highlands — home to the famous Asaro Mudmen. Details Testimonials Arrive: Brisbane, Australia "We experienced great adventures in this seldom visited and wonderful land." Depart: Brisbane, Australia John P. Duration: 11 Days "This was my 10th trip with MT Sobek and I hope to Group Size: 6–16 Guests do more!" Maria B. Minimum Age: 13 Years Old Activity Level: . REASON #01 REASON #02 REASON #03 MT Sobek has been offering unique Our itinerary has been crafted in This itinerary is one of the few to and immersive adventures in Papua consultation with expert local guides include access to the amazing New Guinea for 3 years — with who understand the complexities Kenu and Kundu festival, an every departure a sell-out success. of traveling in Papua New Guinea. annual event with over 600 tribes. ACTIVITIES LODGING CLIMATE Immersive cultural encounters, Enjoy stays in comfortable hotels, In the lowland and coastal areas fjord cruising with opportunities rated among Papua New Guinea's it will be hot with high humidity.