PNG Highlands Joint Programme 2020-2022

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experiences, Challenges and Lessons Learnt in Papua New Guinea

Practice BMJ Glob Health: first published as 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003747 on 3 December 2020. Downloaded from Mortality surveillance and verbal autopsy strategies: experiences, challenges and lessons learnt in Papua New Guinea 1 1 2 3 4 John D Hart , Viola Kwa, Paison Dakulala, Paulus Ripa, Dale Frank, 5 6 7 1 Theresa Lei, Ninkama Moiya, William Lagani, Tim Adair , Deirdre McLaughlin,1 Ian D Riley,1 Alan D Lopez1 To cite: Hart JD, Kwa V, ABSTRACT Summary box Dakulala P, et al. Mortality Full notification of deaths and compilation of good quality surveillance and verbal cause of death data are core, sequential and essential ► Mortality surveillance as part of government pro- autopsy strategies: components of a functional civil registration and vital experiences, challenges and grammes has been successfully introduced in three statistics (CRVS) system. In collaboration with the lessons learnt in Papua New provinces in Papua New Guinea: (Milne Bay, West Government of Papua New Guinea (PNG), trial mortality Guinea. BMJ Global Health New Britain and Western Highlands). surveillance activities were established at sites in Alotau 2020;5:e003747. doi:10.1136/ ► Successful notification and verbal autopsy (VA) District in Milne Bay Province, Tambul- Nebilyer District in bmjgh-2020-003747 strategies require planning at the local level and Western Highlands Province and Talasea District in West selection of appropriate notification agents and VA New Britain Province. Handling editor Soumitra S interviewers, in particular that they have positions of Provincial Health Authorities trialled strategies to improve Bhuyan trust in the community. completeness of death notification and implement an Additional material is ► It is essential that notification and VA data collec- ► automated verbal autopsy methodology, including use of published online only. -

Agricultural Systems of Papua New Guinea Working Paper No. 8

AUSTRALIAN AGENCY for INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AGRICULTURAL SYSTEMS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA Working Paper No. 8 EASTERN HIGHLANDS PROVINCE TEXT SUMMARIES, MAPS, CODE LISTS AND VILLAGE IDENTIFICATION R.M. Bourke, B.J. Allen, RL. Hide, D. Fritsch, R. Grau, P. Hobsbawn, E. Lowes and D. Stannard REVISED and REPRINTED 2002 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY · PAPUA NEW GUINEA DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE AND LIVESTOCK UNIVERSITY OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA AGRICULTURAL SYSTEMS OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA Working Paper No. 8 EASTERN HIGHLANDS PROVINCE TEXT SUMMARIES, MAPS, CODE LISTS AND VILLAGE IDENTIFICATION R.M. Bourke, B.J. Allen, R.L. Hide, D. Fritsch, R. Grau, P. Hobsbawn, E. Lowes and D. Stannard Department of Human Geography, The Australian National University, ACT 0200, Australia REVISED and REPRINTED 2002 Correct Citation: Bourke, R.M., Allen, B.J., Hide, R.L., Fritsch, D., Grau, R., Hobsbawn, P., Lowes, E. and Stannard, D. (2002). Eastern Highlands Province: Text Summaries, Maps, Code Lists and Village Identification. Agricultural Systems of Papua New Guinea Working Paper No. 8. Land Management Group, Department of Human Geography, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University, Canberra. Revised edition. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry: Eastern Highlands Province: text summaries, maps, code lists and village identification. Rev. ed. ISBN 0 9579381 8 7 1. Agricultural systems – Papua New Guinea – Eastern Highlands Province. 2. Agricultural geography – Papua New Guinea – Eastern Highlands Province. 3. Agricultural mapping – Papua New Guinea – Eastern Highlands Province. I. Bourke, R.M. (Richard Michael). II. Australian National University. Land Management Group. (Series: Agricultural systems of Papua New Guinea working paper; no. -

Papua New Guinea

PAPUA NEW GUINEA INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION NEWSLETTER: Apr—Jun 2020 Members of Kumin community constructing their Community Hall supported by IOM through the UN Highlights Peace Building Fund in Southern Highlands Province. © Peter Murorera/ IOM 2020 ◼ IOM strengthened emergency ◼ IOM reinforced peacebuilding ◼ IOM supported COVID-19 Risk preparedness in Milne Bay and efforts of women, men and youth Communication and Community Hela Provinces through training from conflict affected communities Engagement activities in East Sepik, disaster management actors on through training in Community East New Britain, West New Britain, use of the Displacement Tracking Peace for Development Planning Morobe, Oro, Jiwaka, Milne Bay, Matrix. and provision of material support in Madang, and Western Provinces. Southern Highlands Province. New Guinea (PNG) Fire Service, PNG Defense Force, DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX police, churches, local community representatives and Recognizing Milne Bay and Hela Provinces’ vulnerabilities volunteers, private sector and the United Nations (UN). to natural and human-induced hazards such as flooding Participants were trained and upskilled on data and tribal conflict that lead to population displacement, gathering, data management and analysis to track IOM through funding from USAID delivered Displacement population displacement and inform targeted responses. Tracking Matrix (DTM) trainings to 73 participants (56 men and 17 women) from the two Provinces. IOM’s DTM was initially utilized in Milne Bay following a fire in 2018 and in Hela following the M7.5 earthquake The trainings on the DTM information gathering tool, that struck the Highlands in February that same year. The held in Milne Bay (3-5 June 2020) and Hela (17-19 June DTM recorded critical data on persons displaced across 2020) attracted participants from the Government the provinces that was used for the targeting of (Provincial, District and Local Level), Community-Based humanitarian assistance. -

Papua New Guinea (And Comparators)

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized BELOW THE GLASS FLOOR Analytical Review of Expenditure by Provincial Administrations on Rural Health from Health Function Grants & Provincial Internal Revenue JULY 2013 Below the Glass Floor: An Analytical Review of Provincial Administrations’ Rural Health Expenditure Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone: 978-750- 8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street, NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax 202-522-2422; email: [email protected]. - i - Below the Glass Floor: An Analytical Review of Provincial Administrations’ Rural Health Expenditure Table of Contents Acknowledgment ......................................................................................................................... 5 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................. -

20191227 PVR Loans 2486 2497 PNG Highlands Region Road

Validation Report December 2019 Papua New Guinea: Highlands Region Road Improvement Investment Program-Project 1 Reference Number: PVR-652 Project Number: 40173-023 MFF Number: 0029 Loan Number: 2496 and 2497 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank DMF – design and monitoring framework DOW – Department of Works EIRR – economic internal rate of return km – kilometer MFF – multitranche financing facility NRA – National Roads Authority NTDP – national transportation development plan PCR – project completion report PNG – Papua New Guinea TA – technical assistance NOTE In this report, “$” refers to United States dollars. Director General Marvin Taylor-Dormond, Independent Evaluation Department (IED) Deputy Director General Veronique Salze-Lozac’h, IED Director Nathan Subramaniam, Sector and Project Division (IESP) Team Leader Toshiyuki Yokota, Principal Evaluation Specialist, IESP The guidelines formally adopted by the Independent Evaluation Department (IED) on avoiding conflict of interest in its independent evaluations were observed in the preparation of this report. To the knowledge of IED management, there were no conflicts of interest of the persons preparing, reviewing, or approving this report. The final ratings are the ratings of IED and may or may not coincide with those originally proposed by the consultants engaged for this report. In preparing any evaluation report, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, IED does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal -

Operational Highlights 2018

NEWSLETTER PAPUA NEW GUINEA OPERATIONAL HIGHLIGHTS 2018 JANUARY - DECEMBER 2018 The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is an impartial, neutral and independent humanitarian organization that was founded in 1863 to help people affected by armed conflict or other violence. We have been working in Papua New Guinea (PNG) since 2007 as part of the regional delegation in the Pacific based in Suva, Fiji. Our mandate is to do everything we can to protect the dignity of people and relieve their suffering. We also seek to prevent hardship by promoting and strengthening humanitarian law and championing universal humanitarian principles. The PNG Red Cross Society (PNGRCS) is a close partner in our efforts. Here’s a snap shot of our activities in 2018: PROTECTING VULNERABLE PEOPLE The ICRC visits places of detention in correctional institutions and police lock-ups to monitor the living condition and treatment of detainees. Our reports and findings from the visits are treated as confidential and shared only with the authorities concerned and recommendations are implemented with their support. The ICRC also assists authorities with distribution of hygiene material, recreational items and medical equipment. Projects on water and sanitation are also implemented in many facilities. In 2018, we: • Visited 15 places of detention in areas of operations in PNG. • Provided recreational items, hygiene kits and blankets to police lock-ups and correctional institutions. • Facilitated correctional services officers to attend two training programmes abroad and helped a medical doctor participate in a health-in-detention training in Bangkok and Cambodia. • Facilitated first-aid training of correctional services staff in coordination with PNGRCS. -

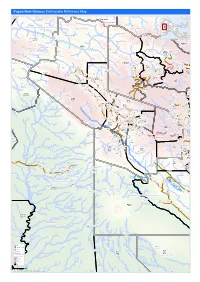

Earthquake Reference Map

Papua New Guinea: Earthquake Reference Map Telefomin London Rural Lybia Telefomin Tunap/Hustein District Ambunti/Drekikier District Kaskare Akiapjmin WEST SEPIK (SANDAUN) PROVINCE Karawari Angoram EAST SEPIK PROVINCE Rural District Monduban HELA PROVINCE Wundu Yatoam Airstrip Lembana Kulupu Malaumanda Kasakali Paflin Koroba/Kopiago Kotkot Sisamin Pai District Emo Airstrip Biak Pokale Oksapmin Liawep Wabag Malandu Rural Wayalima District Hewa Airstrip Maramuni Kuiva Pauteke Mitiganap Teranap Lake Tokom Rural Betianap Puali Kopiago Semeti Oksapmin Sub Aipaka Yoliape Waulup Oksapmin District ekap Airport Rural Kenalipa Seremty Divanap Ranimap Kusanap Tomianap Papake Lagaip/Pogera Tekin Winjaka Airport Gawa Eyaka Airstrip Wane 2 District Waili/Waki Kweptanap Gaua Maip Wobagen Wane 1 Airstrip aburap Muritaka Yalum Bak Rural imin Airstrip Duban Yumonda Yokona Tili Kuli Balia Kariapuka Yakatone Yeim Umanap Wiski Aid Post Poreak Sungtem Walya Agali Ipate Airstrip Piawe Wangialo Bealo Paiela/Hewa Tombaip Kulipanda Waimalama Pimaka Ipalopa Tokos Ipalopa Lambusilama Rural Primary Tombena Waiyonga Waimalama Taipoko School Tumundane Komanga ANDS HIG PHaLin Yambali Kolombi Porgera Yambuli Kakuane C/Mission Paiela Aspiringa Maip Pokolip Torenam ALUNI Muritaka Airport Tagoba Primary Kopetes Yagoane Aiyukuni SDA Mission Kopiago Paitenges Haku KOPIAGO STATION Rural Lesai Pali Airport School Yakimak Apostolic Mission Politika Tamakale Koemale Kambe Piri Tarane Pirika Takuup Dilini Ingilep Kiya Tipinini Koemale Ayene Sindawna Taronga Kasap Luth. Yaparep -

ENVIRONMENTAL and SOCIAL BASELINE REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized and IMPACT ASSESSMENT

ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL BASELINE REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized AND IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR THE PNG AGRICULTURE COMMERCIALIZATION AND Public Disclosure Authorized DIVERSIFICATION PROJECT (PACD) Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared for the Department of Agriculture and Livestock March 2019 Public Disclosure Authorized 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 4 A.1 Methodology .......................................................................................................... 4 A.2 Project Description ................................................................................................ 5 A.3 Geographical coverage .......................................................................................... 6 PART ONE: BASELINE REPORT ......................................................................................... 7 B. Country Profile .............................................................................................................. 7 B.1 System of Government .......................................................................................... 8 National .............................................................................................................................. 8 Provincial ........................................................................................................................... 9 District............................................................................................................................. -

48444-004: Sustainable Highlands

Initial Environmental Examination (Updated as of August 2019) Project Number: 48444-004 Date: August 2019 Document status: Updated Version PNG: Sustainable Highlands Highway Investment Program – Tranche 1 Prepared by the Department of Works (DOW) for the Asian Development Bank This Initial Environmental Examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or Staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (As of 31 July 2019) Currency Unit – Kina (K) K1.00 = $ 0.2945 $1.00 = K3.3956 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank AEP – Aggregate Extraction Plan AIDS – Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome BOD - Biochemical Oxygen Demand BOQ – Bill of Quantities CEMP - Contractor’s Environmental Management Plan CEPA – Conservation and Environmental Protection Authority CEPA-MD – CEPA-Managing Director CRVA _ Climate Risk Vulnerability Assessment CSC - Construction Supervision Consultant DLPP - Department of Lands and Physical Planning DMR – Department of Mineral Resources DNPM - Department of National Planning and Monitoring DOW – Department of Works EARF – Environmental Assessment and Review Framework EHSG _ Environmental Health and Safety Guidelines -

Integrated Land Management, Restoration of Degraded Landscapes and Natural Capital Assessment in the Mountains of Papua New Guinea

5/7/2020 WbgGefportal Project Identification Form (PIF) entry – Full Sized Project – GEF - 7 Integrated land management, restoration of degraded landscapes and natural capital assessment in the mountains of Papua New Guinea Part I: Project Information GEF ID 10580 Project Type FSP Type of Trust Fund GET CBIT/NGI CBIT NGI Project Title Integrated land management, restoration of degraded landscapes and natural capital assessment in the mountains of Papua New Guinea Countries Papua New Guinea Agency(ies) UNEP Other Executing Partner(s) Executing Partner Type Conservation and Environment Protection Authority (CEPA) Government https://gefportal.worldbank.org 1/61 5/7/2020 WbgGefportal GEF Focal Area Multi Focal Area Taxonomy Focal Areas, Land Degradation Neutrality, Land Degradation, Land Cover and Land cover change, Carbon stocks above or below ground, Land Productivity, Biodiversity, Mainstreaming, Extractive Industries, Forestry - Including HCVF and REDD+, Agriculture and agrobiodiversity, Financial and Accounting, Payment for Ecosystem Services, Natural Capital Assessment and Accounting, Species, Threatened Species, Influencing models, Transform policy and regulatory environments, Strengthen institutional capacity and decision-making, Demonstrate innovative approache, Stakeholders, Private Sector, Individuals/Entrepreneurs, SMEs, Beneficiaries, Civil Society, Non-Governmental Organization, Community Based Organization, Local Communities, Communications, Awareness Raising, Education, Public Campaigns, Type of Engagement, Partnership, Information -

Provincial Scoping Review Report Enga Province November 2020

Provincial Scoping Review Report Enga Province November 2020 Dendrobium engae 1 | Page Disclaimer Copyright © 2020 Global Green Growth Institute Jeongdong Building 19F 21-15 Jeongdong-gil Jung-gu, Seoul 04518 Republic of Korea This report was produced as part of a scoping review exercise conducted in three provinces: Enga, Milne Bay and New Ireland. Sections 1-4 of all three reports are similar as they contain information that is common to all three provinces. The Global Green Growth Institute does not make any warranty, either express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or any third party’s use or the results of such use of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed of the information contained herein or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. The text of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit uses, provided that acknowledgement of the source is made. The views and opinions of the authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the Global Green Growth Institute. 2 | Page Description of image on the front page Dendrobium engae, commonly known as the Enga Dendrobium, is a rare orchid that is endemic to the highlands of Papua New Guinea. It is a medium-sized epiphyte that grows on large tree branches at elevations of 1800 to 3500 meters in cool to cold climates. It is more commonly found in Enga Province, as compared to other highlands provinces, and therefore, is depicted on the Enga Provincial Flag. -

Food Project PNG Food Profile

THE INDEPENDENT STATE OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA: PEOPLE & CUISINE The information presented here has been drawn from a combination of primary sources (interviews with ethnic Papua New Guinean women in Brisbane, Gold Coast & Townsville) and from secondary sources. It has been reviewed for consistency by members of the Queensland PNG community to ensure that information presented is accurate. HACC is a joint Australian Government-State funded program. Copyright © Diversicare 2012 This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License . It can be shared under the conditions specified by this license at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au 2 Table of Contents 1 Background .......................................................................................................................................................5 1.1 History[1] ................................................................................................................................................5 1.2 Regions ..................................................................................................................................................6 1.3 Climate ...................................................................................................................................................6 1.4 Population .............................................................................................................................................6 1.5 Urban vs. Rural populations .................................................................................................................6