Tourism, a Catalyst Promoting Development in Jiwaka Province – Papua New Guinea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papua New Guinea

PAPUA NEW GUINEA INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION NEWSLETTER: Apr—Jun 2020 Members of Kumin community constructing their Community Hall supported by IOM through the UN Highlights Peace Building Fund in Southern Highlands Province. © Peter Murorera/ IOM 2020 ◼ IOM strengthened emergency ◼ IOM reinforced peacebuilding ◼ IOM supported COVID-19 Risk preparedness in Milne Bay and efforts of women, men and youth Communication and Community Hela Provinces through training from conflict affected communities Engagement activities in East Sepik, disaster management actors on through training in Community East New Britain, West New Britain, use of the Displacement Tracking Peace for Development Planning Morobe, Oro, Jiwaka, Milne Bay, Matrix. and provision of material support in Madang, and Western Provinces. Southern Highlands Province. New Guinea (PNG) Fire Service, PNG Defense Force, DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX police, churches, local community representatives and Recognizing Milne Bay and Hela Provinces’ vulnerabilities volunteers, private sector and the United Nations (UN). to natural and human-induced hazards such as flooding Participants were trained and upskilled on data and tribal conflict that lead to population displacement, gathering, data management and analysis to track IOM through funding from USAID delivered Displacement population displacement and inform targeted responses. Tracking Matrix (DTM) trainings to 73 participants (56 men and 17 women) from the two Provinces. IOM’s DTM was initially utilized in Milne Bay following a fire in 2018 and in Hela following the M7.5 earthquake The trainings on the DTM information gathering tool, that struck the Highlands in February that same year. The held in Milne Bay (3-5 June 2020) and Hela (17-19 June DTM recorded critical data on persons displaced across 2020) attracted participants from the Government the provinces that was used for the targeting of (Provincial, District and Local Level), Community-Based humanitarian assistance. -

Papua New Guinea (And Comparators)

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized BELOW THE GLASS FLOOR Analytical Review of Expenditure by Provincial Administrations on Rural Health from Health Function Grants & Provincial Internal Revenue JULY 2013 Below the Glass Floor: An Analytical Review of Provincial Administrations’ Rural Health Expenditure Rights and Permissions The material in this publication is copyrighted. Copying and/or transmitting portions or all of this work without permission may be a violation of applicable law. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/ The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission to reproduce portions of the work promptly. For permission to photocopy or reprint any part of this work, please send a request with complete information to the Copyright Clearance Center Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; telephone: 978-750- 8400; fax: 978-750-4470; Internet: www.copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Office of the Publisher, The World Bank, 1818 H Street, NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax 202-522-2422; email: [email protected]. - i - Below the Glass Floor: An Analytical Review of Provincial Administrations’ Rural Health Expenditure Table of Contents Acknowledgment ......................................................................................................................... 5 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................. -

Bulletin of the World Health Organization

Policy & practice Transforming the health information system using mobile and geographic information technologies, Papua New Guinea Alexander Rosewell,a Phil Shearman,b Sundar Ramamurthyb & Rob Akersc Abstract In the context of declining economic growth, now exacerbated by the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, Papua New Guinea is increasing the efficiency of its health systems to overcome difficulties in reaching global health and development targets. Before 2015, the national health information system was fragmented, underfunded, of limited utility and accessed infrequently by health authorities. We built an electronic system that integrated mobile technologies and geographic information system data sets of every house, village and health facility in the country. We piloted the system in 184 health facilities across five provinces between 2015 and 2016. By the end of 2020, the system’s mobile tablets were rolled out to 473 facilities in 13 provinces, while the online platform was available in health authorities of all 22 provinces, including church health services. Fractured data siloes of legacy health programmes have been integrated and a platform for civil registration systems established. We discuss how mobile technologies and geographic information systems have transformed health information systems in Papua New Guinea over the past 6 years by increasing the timeliness, completeness, quality, accessibility, flexibility, acceptability and utility of national health data. To achieve this transformation, we highlight the importance of considering the benefits of mobile tools and using rich geographic information systems data sets for health workers in primary care in addition to the needs of public health authorities. Introduction lot of mobile device technologies and geographic information systems in the capture and reporting of health data. -

Ecotourism As a Means of Encouraging Ecological Recovery in the Flinders Ranges, South Australia

ECOTOURISM AS A MEANS OF ENCOURAGING ECOLOGICAL RECOVERY IN THE FLINDERS RANGES, SOUTH AUSTRALIA By Emily Moskwa A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Discipline of Geographical and Environmental Studies School of Social Sciences Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences The University of Adelaide May 2008 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures………………………………………………………………………………….…….....v List of Tables…………………………………………………………………………………….….....vi Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………….……viii Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………….………ix Declaration……………………………………………………………………………………….……..x Section I: Preliminaries 1.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................. 2 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Conceptual Basis for Thesis ...................................................................................... 2 1.3 Research Questions ................................................................................................... 3 1.4 Specific Objectives .................................................................................................... 5 1.5 Justifications for Research ........................................................................................ 6 1.6 Structure of the Thesis .............................................................................................. 8 1.7 Conclusion ................................................................................................................ -

Khulo Municipality Tourism Development Plan

KHULO MUNICIPALITY TOURISM DEVELOPMENT PLAN The document was prepared in the framework of the project “Rural Development and Diversification in Khulo Municipality” 1 Content: 1. Outline of assignment objectives, methodology and expected results 2. Overview of the Georgian National Tourism Strategy 2015-2025, presenting current status by statistics and economic indicators; 3. Overview of the tourism development in Adjara region according to the regional tourism strategy 2015-2018. 4. New opportunities for tourism development 5. Trends to be considered for tourism development 6. Value add approach 7. Type of recommended project investment 8. Assessment of local tourism development opportunities through the consultation with LAG (SWOT) and workshop results 9. Examples of the trail planning 10. Proposed tourism action plan for LDS for Khulo municipality Annexes: Annex 1: List of the strategic planning documents Annex 2: Examples of the trails in Khulo municipality Annex 3: Examples of entrepreneurship and services in community based tourism Annex 4: Recommended investment – small grants and contributions per facilities 2 Map of Khulo municipality 3 1. Outline of tourism consultant’s assignment: Tourism development expert has been contracted by PMC Georgia on short term assignment (12 working days, including 3 days of site visit and workshop with LAG). Objective of assignment is to elaborate opportunities and propose action plan to be contributed in to the Local Development Strategy for Khulo municipality. Step 1: detail review of the relevant documentation including LDS obtained from the main national actors (see annex: 1) In addition, contributing international best practices and presenting case examples of the similar investments taking place around other touristic regions of Georgian mountain (example of Kazbegi municipality. -

Operational Highlights 2018

NEWSLETTER PAPUA NEW GUINEA OPERATIONAL HIGHLIGHTS 2018 JANUARY - DECEMBER 2018 The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is an impartial, neutral and independent humanitarian organization that was founded in 1863 to help people affected by armed conflict or other violence. We have been working in Papua New Guinea (PNG) since 2007 as part of the regional delegation in the Pacific based in Suva, Fiji. Our mandate is to do everything we can to protect the dignity of people and relieve their suffering. We also seek to prevent hardship by promoting and strengthening humanitarian law and championing universal humanitarian principles. The PNG Red Cross Society (PNGRCS) is a close partner in our efforts. Here’s a snap shot of our activities in 2018: PROTECTING VULNERABLE PEOPLE The ICRC visits places of detention in correctional institutions and police lock-ups to monitor the living condition and treatment of detainees. Our reports and findings from the visits are treated as confidential and shared only with the authorities concerned and recommendations are implemented with their support. The ICRC also assists authorities with distribution of hygiene material, recreational items and medical equipment. Projects on water and sanitation are also implemented in many facilities. In 2018, we: • Visited 15 places of detention in areas of operations in PNG. • Provided recreational items, hygiene kits and blankets to police lock-ups and correctional institutions. • Facilitated correctional services officers to attend two training programmes abroad and helped a medical doctor participate in a health-in-detention training in Bangkok and Cambodia. • Facilitated first-aid training of correctional services staff in coordination with PNGRCS. -

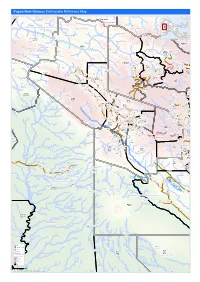

Earthquake Reference Map

Papua New Guinea: Earthquake Reference Map Telefomin London Rural Lybia Telefomin Tunap/Hustein District Ambunti/Drekikier District Kaskare Akiapjmin WEST SEPIK (SANDAUN) PROVINCE Karawari Angoram EAST SEPIK PROVINCE Rural District Monduban HELA PROVINCE Wundu Yatoam Airstrip Lembana Kulupu Malaumanda Kasakali Paflin Koroba/Kopiago Kotkot Sisamin Pai District Emo Airstrip Biak Pokale Oksapmin Liawep Wabag Malandu Rural Wayalima District Hewa Airstrip Maramuni Kuiva Pauteke Mitiganap Teranap Lake Tokom Rural Betianap Puali Kopiago Semeti Oksapmin Sub Aipaka Yoliape Waulup Oksapmin District ekap Airport Rural Kenalipa Seremty Divanap Ranimap Kusanap Tomianap Papake Lagaip/Pogera Tekin Winjaka Airport Gawa Eyaka Airstrip Wane 2 District Waili/Waki Kweptanap Gaua Maip Wobagen Wane 1 Airstrip aburap Muritaka Yalum Bak Rural imin Airstrip Duban Yumonda Yokona Tili Kuli Balia Kariapuka Yakatone Yeim Umanap Wiski Aid Post Poreak Sungtem Walya Agali Ipate Airstrip Piawe Wangialo Bealo Paiela/Hewa Tombaip Kulipanda Waimalama Pimaka Ipalopa Tokos Ipalopa Lambusilama Rural Primary Tombena Waiyonga Waimalama Taipoko School Tumundane Komanga ANDS HIG PHaLin Yambali Kolombi Porgera Yambuli Kakuane C/Mission Paiela Aspiringa Maip Pokolip Torenam ALUNI Muritaka Airport Tagoba Primary Kopetes Yagoane Aiyukuni SDA Mission Kopiago Paitenges Haku KOPIAGO STATION Rural Lesai Pali Airport School Yakimak Apostolic Mission Politika Tamakale Koemale Kambe Piri Tarane Pirika Takuup Dilini Ingilep Kiya Tipinini Koemale Ayene Sindawna Taronga Kasap Luth. Yaparep -

Papua New Guinea Situation Summary and Highlights Upcoming

Papua New Guinea Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Health Situation Report #51 14 December 2020 Period of report: 7 - 13 December 2020 This Situation Report is jointly issued by PNG National Department of Health and World Health Organization once weekly. This Report is not comprehensive and covers information received as of reporting date. Situation Summary and Highlights ❒ As of 13 December (12:00 pm), there have been 725 COVID-19 cases and eight COVID-19 deaths reported in Papua New Guinea. From the period of 7 to 14 December, there have been 44 new cases: 35 from West New Britain, 4 from Western Highlands, 3 from National Capital District, and 2 from East New Britain. The total number of provinces that have reported COVID-19 cases to date is sixteen, including AROB. ❒ A multidisciplinary team from the NCC (surveillance, clinical management, risk communication, community engagement clusters and provincial coordination) travelled to Southern Highlands Province to provide technical support for COVID-19 preparedness and response. Upcoming Events and Priorities ❒ Coordination: Two inter-cluster provincial visits by NCC teams (comprised of representatives from surveillance, laboratory, clinical management, and risk communication and community engagement) are scheduled to Milne Bay and Southern Highlands from the week of 14 December. The COVID-19 Summit has been rescheduled to take place from 25 January to 5 February 2021 at the APEC Haus in Port Moresby. ❒ Surveillance: Additional planning and support for the current outbreak in West New Britain Province are underway. Further data analysis will be conducted to gain a deeper understanding of surveillance issues in the country. -

DEPARTMENT of HISTORY & TOURISM MANAGEMENT KAKATIYA UNIVERSITY Scheme of Instruction and Examination Master of Tourism Manag

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY & TOURISM MANAGEMENT KAKATIYA UNIVERSITY Scheme of Instruction and Examination Master of Tourism Management (Regular) Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) w.e.f. 2017-2018 SEMESTER-I Paper Paper Title Contact Credits Internal External Total Hours 1 Cultural History of India (From Earliest 4 4 20 80 100 Times To 700 A.D.) 2 Geography for Tourism 4 4 20 80 100 3 Tourism Management 4 4 20 80 100 4 Tourism Products 4 4 20 80 100 5 Organizational Behaviour 4 4 20 80 100 6 Entrepreneurship 4 4 20 80 100 7 Tutorials/Seminars 2 50 50 Total 24 26 170 480 650 SEMESTER-II Paper Paper Title Contact Credits Internal External Total Hours 1 Cultural History of India (From 8th C. To 4 4 20 80 100 17th C. A.D.) 2 Travel Management 4 4 20 80 100 3 Travel and Accommodation 4 4 20 80 100 4 Tourism Marketing 4 4 20 80 100 5 Computing and Information System in 4 4 20 80 100 Tourism 6 Hospitality Management 4 4 20 80 100 7 Tutorials/Seminars 2 50 50 Total 24 26 170 480 650 SEMESTER-III Paper Paper Title Contact Credits Internal External Total Hours 1 Cultural History of India (From 17 Th To 4 4 20 80 100 20th Century A.D) 2 Business Communication 4 4 20 80 100 3 Foreign Language 4 4 20 80 100 (German/French/Japanese) 4 Ecology, Environment and Tourism 4 4 20 80 100 5 (A) Basic Airfare and Ticketing 4 4 20 80 100 (B) Front Office Management 6 Mice Management 4 4 20 80 100 7 Tutorials/Seminars 2 50 50 Total 24 26 170 480 650 SEMESTER-IV Paper Paper Title Contact Credits Internal External Total Hours 1 Cultural Tourism in Telangana 4 4 20 80 100 2 Tourism Development 4 4 20 80 100 3 Contemporary Issues in Tourism 4 4 20 80 100 4 Research Methodology 4 4 20 80 100 5 (A) House Keeping Management 4 4 20 80 100 (B) Human Resource Management in Tourism 6 Project Work 4 4 20 80 100 7 Historical and Cultural Tourism in 4 4 20 80 100 Telangana 8 Tutorials/Seminars 2 50 50 Total 28 30 190 560 750 Restructuring of Syllabus according to Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) & Scheme of Instruction and Examination for Master of Tourism Management (Regular) w.e.f. -

19 Tourism and Sustainability

MakutanoJunction A Kenyan TV soap opera Activity Helping you develop the Global Dimension across the curriculum 19 Tourism and sustainability Activity description • To use ICT to create a PowerPoint presentation to persuade tourists to plan and book sustainable This activity aims to raise awareness of the impacts holidays. of tourism on a country and to encourage students to design their own sustainable holiday experience of Kenya. Curriculum links • Citizenship KS3 and KS4: Aims 1.2 Rights and responsibilities 2.1 Critical thinking and enquiry • To discuss the benefits and adverse impacts of • Geography KS3: tourism. 1.1 Place • To raise awareness of the advantages of sustainable 1.7 Cultural understanding and diversity tourism. 2.4 Geographical communication • ICT KS3 and KS4: What you need? 1.1 Capability 1.5 Critical evaluation True and False quiz 2.1 Finding information Access to the internet and PowerPoint for 2.2 Developing ideas all pupils Further details of how this activity meets requirements ‘Explore Kenya’ worksheet in activity 1 of the new Secondary Curriculum appear on the Curriculum Links table. For subjects outside the www.makutanojunction.org.uk © Copyright Makutano Junction. You may reproduce this document for educational purposes only. statutory curriculum, check your own exam board for their requirements. For general information on the GLOBAL DIMENSION Global Dimension across the curriculum, see www. globaldimension.org.uk Underlying the concept of a global dimension to the curriculum are eight key concepts. This activity covers the following seven: What you do Citizenship – gaining the knowledge, 1 In pairs decide on which of the statements about skills and understanding necessary tourism in Kenya are true and which are false. -

Integrated Land Management, Restoration of Degraded Landscapes and Natural Capital Assessment in the Mountains of Papua New Guinea

5/7/2020 WbgGefportal Project Identification Form (PIF) entry – Full Sized Project – GEF - 7 Integrated land management, restoration of degraded landscapes and natural capital assessment in the mountains of Papua New Guinea Part I: Project Information GEF ID 10580 Project Type FSP Type of Trust Fund GET CBIT/NGI CBIT NGI Project Title Integrated land management, restoration of degraded landscapes and natural capital assessment in the mountains of Papua New Guinea Countries Papua New Guinea Agency(ies) UNEP Other Executing Partner(s) Executing Partner Type Conservation and Environment Protection Authority (CEPA) Government https://gefportal.worldbank.org 1/61 5/7/2020 WbgGefportal GEF Focal Area Multi Focal Area Taxonomy Focal Areas, Land Degradation Neutrality, Land Degradation, Land Cover and Land cover change, Carbon stocks above or below ground, Land Productivity, Biodiversity, Mainstreaming, Extractive Industries, Forestry - Including HCVF and REDD+, Agriculture and agrobiodiversity, Financial and Accounting, Payment for Ecosystem Services, Natural Capital Assessment and Accounting, Species, Threatened Species, Influencing models, Transform policy and regulatory environments, Strengthen institutional capacity and decision-making, Demonstrate innovative approache, Stakeholders, Private Sector, Individuals/Entrepreneurs, SMEs, Beneficiaries, Civil Society, Non-Governmental Organization, Community Based Organization, Local Communities, Communications, Awareness Raising, Education, Public Campaigns, Type of Engagement, Partnership, Information -

Jiwaka Province

DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION EDUCATION VACANCY GAZETTE 2021 Published by Authority Vol. 44, No. 01 WAIGANI, Friday 16th July 2021 _ JIWAKA PROVINCE - 2 - T A B L E O F CO N T E N T S Pages SECTION A: INTRODUCTION/PREAMBLE DEFINITION……………………………………………………………… 4 OPERATIONAL TIMETABLE 1 OF 2021……………………………… 7 CHURCH CODE AND PHILOSOPHIES……………………….……...... 8 CODE FOR SUBJECT AREAS…………………………………….……. 13 POSTAL ADDRESS (Selection & Appointing Authorities) ……………. 14 SECTION B: ADVERTISED TEACHING VACANCIES PRIMARY SCHOOLS…………………………………………………… 15 HIGH SCHOOLS ………………………………………………………….. 48 SECONDARY SCHOOLS …………………………...……………….…... 52 VOCATIONAL CENTRES.....….………................................................. 56 SECTION C: MISCELLANEOUS - ELIGIBILITY AWARDS ELIGIBILITY LISTS …………………………………………………… 59 - 3 - PAPUA NEW GUINEA TEACHING SERVICE VACANCIES (TEACHING SERVICE ACT NO. 12 OF 1988) DEFINITION Non-citizens outside PNG are not eligible to apply. In this preamble – WHO MUST APPLY “advertising authority” means the National Education Board (NEB) Concurrent Occupant – is a teacher who is substantive to “appointing authority” means the Provincial the level but is not the tenure holder of the position. The Education Board (PEB) and National teacher may have tenure on the same level elsewhere. Education Board (NEB) for national Unless they intend to return to their tenure position they must Institutions. apply for a new tenure position. “auxiliary member” means a person (non-citizen) who has been admitted to auxiliary membership of the Teaching Acting Occupant – The person who is acting on the position Service. higher than his or her substantive position. “member of the Teaching Service” or “member” means a national including a naturalized citizen who is a full member, a Anyone who is acting or a concurrent occupant must: provisional member, or an associate member of the Teaching apply upwards using their current eligibility.