International Association for Literary Journalism Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extensions of Remarks 10509

May 9, 1979 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 10509 MENT REPORT.-The Secretary shall set forth available to the United States Geological -Page 274, line 1, strike "(b) (1)" and in in each report to the Congress under the Survey, the Bureau of Mines, or any other lieu thereof insert "(c) (2)". Mining and Minerals Policy Act of 1970 a agency or instrumentality of the United Page 333, lines 14 and 15, strike "after the summary of the pertinent information States. date of enactment of this Act". (other than proprietary or other confidential (Additional technical amendments to -Page 275, line 8, change "28" to "27" and information) relating to minerals which is Udall-Anderson substitute (H.R. 3651) .) change "33" to "34". EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS A NONFUEL MINERAL POLICY: WE Of course, the usual antagonists are lined These Americans descend from .Japa CAN NO LONGER WAIT up on each side of this policy debate. But, nese, Chinese, Korean, and Filipino an as Nevada Congressman J. D. Santini points cestors, as well as from Hawaii and t'iher out in our p . 57 feature, their arguments Pacific Islands such as Samoa, Fiji, and HON. JIM SANTINI go by one another like ships in the night with nothing happening-until the lid blows Tahiti. In southern California, where OF NEVADA off. we have the greatest concentration of IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES But, how do you get the public excited Asian and Pacific Americans anywhere Wednesday, May 9, 1979 about metal shortages? in the Nation, their valuable involvemept Even Congressman Santini's well-meant in the growth and prosperity of our local • Mr. -

The Lady Onstage by Erin Bregman

The Lady Onstage by Erin Bregman Resource Guide for Teachers Created by: Lauren Bloom Hanover, Director of Education Jeff Denight, Dramaturgy Intern 1 Table of Contents About Profile Theatre 3 How to Use This Resource Guide 4 The Artists 5 Lesson 1: Historical Context 6 Classroom Activities: 1) Biography and Context 6 2) Knipper and Chekov in Their Own Words 6 3) The Development of The Lady Onstage 8 4) Considering Contemporary Cultural Shifts (Homework) 9 Supplemental Materials 10 Lesson 2: The Process of Play Development 21 Classroom Activities 1) Where Do New Plays Come From? 21 2) Exploring a Play We Know 23 3) How to Start - the Development Process in Action 24 4) Starting Your Own Play (Homework) 24 Supplemental Materials 26 Lesson 3: One Person Plays - A Unique Challenge 34 Classroom Activities 1) Exploring Single-Character Monologues 34 2) Exploring Multi-character Solo Performances 35 3) Writing Your Own Monologue (Homework) 36 Supplemental Materials 38 Lesson 4: Chekhov Today: Translations and Adaptations 41 Classroom Activities 1) Exploring Translations 42 2) Exploring Work Inspired by Chekhov 42 3) Creating Your Own Adaptation 43 Supplemental Materials 44 Lesson 5: Reflecting on the Performance Classroom Activities 1) Classroom Discussion and Reflection 52 2) What We’ve Learned 52 3) Creative Writing (Homework) 53 2 About Profile Theatre Profile Theatre was founded in 1997 with the mission of celebrating the playwright’s contribution to live theater. Each year Profile produces a season of plays devoted to a single playwright, engaging with our community to explore that writer’s vision and influence on theatre and the world at large. -

Here I Come with All My Black Girl Magic”: Black Women and Girls’ Experiences in Predominantly White Independent Private Schools

“HERE I COME WITH ALL MY BLACK GIRL MAGIC”: BLACK WOMEN AND GIRLS’ EXPERIENCES IN PREDOMINANTLY WHITE INDEPENDENT PRIVATE SCHOOLS BY DEVEAN R. OWENS DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education Policy, Organization and Leadership with a concentration in Diversity and Equity in Education in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2020 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Anjalé Welton, Chair Professor Ruth Nicole Brown Professor Adrienne Dixson Professor Helen Neville Abstract Within independent private schools specifically, Black women and girls endure feelings of rejection, isolation, and inadequacy all whilst trying to maintain their academic or career success and a positive self-perception. Through the lenses of Black Feminist Thought and Critical Race Theory, this dissertation presents Black women and girls’ true experiences in PWIS which defy dominant deficit beliefs. Participants detailed the racism, erasure, and trauma they endured and the detrimental effects these experiences caused in their lives. They also expressed the importance and value of their relationships with one another. These relationships provided them with the affirmation and confidence they needed to believe in and stand up for themselves. Black women and girls engage in various resistance strategies through living authentically, challenging dominant norms, and advocating for themselves and others in the school community. ii Acknowledgements Students & participants… Thank you for inspiring me! Thank you for taking the time to participate in this study. Drs. Welton, Brown, Dixson, Neville, and Zamani-Gallaher… Thank you for challenging me to think more critically and seeing me through this journey. -

Hollywoodland Text.Pdf

HOLLYWOODLAND HOLLYWOODLAND an american fairy tale JENNIFER BANASH Impetus Press PO Box 10025 Iowa City, IA 52240 www.impetuspress.com [email protected] Publisher Note: This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. ISBN 0-9776693-0-0 September 2006 Copyright © 2006 Impetus Press. All rights reserved. for my father I’m going to be in the movies if I have to fuck Bela Lugosi to get there. Actresses are a little like race horses. It’s difficult for us when the race is cancelled. This is an attempt at the ultimate motion picture. ••• 2:00 AM, 82 ° She is in her car when it happens, the black roads around Mulholland winding and twisting, unrolling like the soft dark fabric of a magic carpet. Her eyes blur and she squints them repeatedly, leaning forward to see. The needle on the speedometer flies up past eighty, then ninety, the tendons in her right arm straining, muscles burning as she grips the wheel one-handed. Sierra loves to drive more than anything, the feeling of weightlessness, careening through the air, unstoppable. She was fucking unstoppable. She could feel the kid in the seat next to her getting nervous, moving back and forth in his seat, one hand clutching the belt that cut across his skinny frame. His jeans make a harsh scraping sound. The rasp of denim on leather annoys her, and she closes her eyes. -

Race Trouble: an Exploration of Race Relations in Zebra Crossing, Coconut and the Book of Memory by Meg Vandermerwe, Kopano Matlwa and Petina Gappah

Race Trouble: An exploration of race relations in Zebra Crossing, Coconut and The Book of Memory by Meg Vandermerwe, Kopano Matlwa and Petina Gappah Travis McCabe March 2020 English Studies College of Arts Faculty of Humanities Pietermaritzburg Campus University of Kwa-Zulu Natal 1 DECLARATION Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, in the Graduate Programme in English Studies, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. I, Travis McCabe, declare that 1. The research reported in this thesis, except where otherwise indicated, is my original research. 2. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. 3. This thesis does not contain other persons’ data, pictures, graphs or other information, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other persons. 4. This thesis does not contain other persons' writing, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other researchers. Where other written sources have been quoted, then: a. Their words have been re-written but the general information attributed to them has been referenced b. Where their exact words have been used, then their writing has been placed in italics and inside quotation marks, and referenced. 5. This thesis does not contain text, graphics or tables copied and pasted from the Internet, unless specifically acknowledged, and the source being detailed in the thesis and in the References sections. 12 March 2020 Travis McCabe Supervisor: 214542406 Dr Claire Scott _______________ _______________ Signature Signature 2 Abstract Despite the formalised abolishment of both apartheid and colonialism, it would in many respects be remiss to conclude that the legacy of these systems of oppression do not continue to exert some level of influence on the attitudes and behaviour of individuals and groups. -

Stumptown Kid

Stumptown Kid Stumptown Kid written by Carol Gorman and Ron J. Findley Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Text © 2005 by Carol Gorman and Ron J. Findley First trade paperback edition published April 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Loraine M. Joyner Book design by Melanie McMahon Ives Background baseball player photo courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, George Grantham Bain Collection. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gorman, Carol. Stumptown kid / written by Carol Gorman and Ron J. Findley.-- 1st ed. p. cm. Summary: In a small Iowa town in 1952, eleven-year-old Charlie Nebraska, whose father died in the Korean War, learns the meanings of both racism and heroism when he befriends a black man who had played baseball in the Negro Leagues. ISBN 13: 978-1-56145-719-9 (ebook) [1. Baseball--Fiction. 2. Coaching (Athletics)--Fiction. 3. Prejudices--Fiction. 4. African Americans--Fiction. 5. Single-parent families--Fiction. 6. Iowa--History--20th century--Fiction.] I. Findley, Ron J. II. Title. PZ7.G6693St 2005 [Fic]--dc22 2004019835 With love to my first writing teacher, my best friend, and husband, Ed Gorman —C. G. To my children, Jeff and Kris, and to my grandchildren— Ashley, Haley, Adam, Aubrey, and Hannah —R. -

Fall 2021 Kids OMNIBUS

FALL 2021 RAINCOAST OMNIBUS Kids This edition of the catalogue was printed on May 13, 2021. To view updates, please see the Fall 2021 Raincoast eCatalogue or visit www.raincoast.com Raincoast Books Fall 2021 - Kids Omnibus Page 1 of 266 A Cub Story by Alison Farrell and Kristen Tracy Timeless and nostalgic, quirky and fresh, lightly educational and wholly heartfelt, this autobiography of a bear cub will delight all cuddlers and snugglers. See the world through a bear cub's eyes in this charming book about finding your place in the world. Little cub measures himself up to the other animals in the forest. Compared to a rabbit, he is big. Compared to a chipmunk, he is HUGE. Compared to his mother, he is still a little cub. The first in a series of board books pairs Kristen Tracy's timeless and nostalgic text with Alison Farrell's sweet, endearing art for an adorable treatment of everyone's favorite topic, baby animals. Author Bio Chronicle Books Alison Farrell has a deep and abiding love for wild berries and other foraged On Sale: Sep 28/21 foods. She lives, bikes, and hikes in Portland, Oregon, and other places in the 6 x 9 • 22 pages Pacific Northwest. full-color illustrations throughout 9781452174587 • $14.99 Kristen Tracy writes books for teens and tweens and people younger than Juvenile Fiction / Animals / Baby Animals • Ages 2-4 that, and also writes poetry for adults. She's spent a lot of her life teaching years writing at places like Johnson State College, Western Michigan University, Brigham Young University, 826 Valencia, and Stanford University. -

Winter 2011 • V Ol. 45 No. 4

Winter 2011 • Vol. 45 No. 4 FROM THE MAILBOX Photo: Kelli Herwehe A Word From Hi San Diego Humane Society, BOARD OF TRUSTEES We are really happy in our new home in Pacific Beach! We have three floors to run around Fred Baranowski Dr. Judith T. Muñoz on and jump on the resident cat, Precious, who puts up with us. Our new owners renamed us Chairperson from Cinnamon and Cheyenne to Thelma and Louise, which seems to fit us better since we are Beverly Oster Ornelas Secretary Interim President inseparable. We are the hit at the PB Vet Clinic, since Dr. Farley thinks we are really cute. So far David Hickey life is great! We get fed, have tons of toys, and we like to sleep on our owner’s heads at night. Plus, Chairperson, Finance Committee s you may already know by now, I am volunteering as the San we get to play in the laundry basket! Thank you so much for finding us such good parents. Diane Gilabert Diego Humane Society and SPCA’s interim president and leading Chairperson, Board Governance & Nominating Love, Committee Athe search committee to find a successor for Dr. Mark Goldstein. In Thelma and Louise Susan Davis addition to leading the search with several past and present members of the PS: Louise is the one with the white chest and legs. Chairperson, Development Committee Board of Trustees, my role is to maintain the organization’s legacy of success Sandy Arledge; Allen Blackmore; by continuing its three-year strategic plan with the talented and experienced Robert Brown, Ed.D.; Lee Collins; Hi all my human friends and animal friends at the San Diego Humane Society, Dana Di Ferdinando; Dave Mason; management team already in place. -

Being in Afro-Brazilian Families by Elizabeth Hordge

Home is Where the Hurt Is: Racial Socialization, Stigma, and Well- Being in Afro-Brazilian Families By Elizabeth Hordge Freeman Department of Sociology Duke University Date: _____________________ Approved: ________________________________________ Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, Co-Supervisor _________________________________________ Linda George, Co-Supervisor _________________________________________ Lynn Smith-Lovin _________________________________________ Linda Burton __________________________________________ Sherman James Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Sociology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 ! ABSTRACT Home is Where the Hurt Is: Racial Socialization, Stigma, and Well- Being in Afro-Brazilian Families By Elizabeth Hordge Freeman Department of Sociology Duke University Date: _____________________ Approved: ________________________________________ Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, Co-Supervisor _________________________________________ Linda George, Co-Supervisor _________________________________________ Lynn Smith-Lovin _________________________________________ Linda Burton __________________________________________ Sherman James An abstract submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Sociology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 ! ! Copyright by Elizabeth Hordge Freeman 2012 ! Abstract This dissertation examines racial socialization in Afro-Brazilian families in -

Kramer Dishes out Some Opinions on NFL Draft,Kramer Explains Allure of Baseball and Golf,Kramac the Munificent Divines NBA Trade

Kramer dishes out some opinions on NFL draft The NFL draft is the least exciting “event” in sports. Nothing really happens. A few big guys around our age sit in a big ballroom and wait to have their names called. It’s like high school graduation, but with 10 minutes of prognostication between the announcement of valedictorian and salutatorian. The draft is televised because many Americans will watch virtually anything about football, as evidenced by the success of Craig T. Nelson’s Coach. But the draft is not without its merits. It’s an utterly optimistic event; every fan thinks his/her team will improve through the draft, and it’s hard to fault their logic. Adding a talented young player should have only positive repercussions. But in the highly-monetized world of professional football, top draft picks demand exorbitant salaries based purely on perceived potential. JaMarcus Russell, Ryan Leaf, Charles Rogers, Courtney Brown, Joey Harrington, Robert Gallery, David Carr, etc. have all proven that if teams aren’t careful, they can waste millions of dollars and countless hours of time developing a player who just isn’t talented or hard-working enough to make it in the League. But a track record of exalting failures like the schlubs listed above doesn’t stop the so-called experts from offering their opinion at every possible stage of the draft, including literally 364 days before. Draft experts release their asinine, make-believe mock drafts into the internet to poison the sports fan’s reading enjoyment of both the NFL and college seasons, like so many syringes being dumped into a pit of syringes, a la Saw II. -

Beyond the Pencil Test

BEYOND THE PENCIL TEST Transformations in hair and headstyles, or communicating social change Andre Powe ISSUE 12 April 2009 Why does Black hair have such potency? To whom is Black hair speaking? What messages does Black hair communicate? Each hairstyle choice tells an intimate story of the wearer, disclosing a personal narrative to spectators. In this article, Andre Powe analyzes hair as sign, symbol, text, and a highly specialized language of representation. RIO DE JANEIRO, Brazil (AP) - What struck the Brazilian woman most forcibly as she watched U.S. election returns on television was seeing President–elect Barack Obama's two young daughters. “I can't believe those two little girls with hair like mine will be in the White House,'' said 31-year-old Carolina Iootty Dias, putting her hand to her head, tears in her eyes as she watched the screen... “Obama win forces Brazil to take a reality check”, by David Bradley (November 5, 2008) HAIR AND COMMUNICATION Why does Black hair have such potency? To whom is Black hair speaking? What messages does Black hair communicate? Hairstyles are what every human being possesses, but few give the subject serious consideration, particularly as an aspect of communication. Fiske (1990) identifies two schools of thought in studying communication: one track recognizes communication as the transmission of messages; the other sees communication as the production and the exchange of meanings. According to Fiske, this second school of thought “does not consider misunderstandings to be evidence of communication failure – they may result from cultural differences between sender and receiver”. In either case, most importantly, his view is that “Communication is talking to one another, it is television, it is spreading information, it is our hairstyle”. -

Read an Excerpt

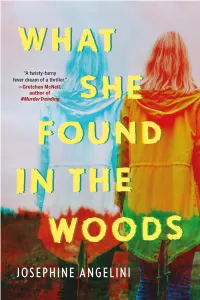

WhatSheFoundInTheWoods_INT.indd 1 8/14/20 1:23 PM WhatSheFoundInTheWoods_INT.indd 2 8/14/20 1:23 PM WhatSheFoundInTheWoods_INT.indd 3 8/14/20 1:23 PM Copyright © 2019, 2021 by Josephine Angelini Cover and internal design © 2021 by Sourcebooks Cover design by Mark Swan Cover images © Maria Heyens/Arcangel; Clement M/Unsplash Internal design by Danielle McNaughton/Sourcebooks Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems— except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks. The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author. All brand names and product names used in this book are trademarks, registered trademarks, or trade names of their respective holders. Sourcebooks is not associated with any product or vendor in this book. Published by Sourcebooks Fire, an imprint of Sourcebooks P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410 (630) 961-3900 sourcebooks.com Originally published in 2019 in the United Kingdom by Macmillan Children’s Books, an imprint of Pan Macmillan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Angelini, Josephine, author. Title: What she found in the woods / Josephine Angelini. Description: Naperville, Illinois : Sourcebooks Fire, [2020] | Audience: Ages 14. | Audience: Grades 10-12. | Summary: While summering in her grandparents' small Oregon town, where a serial murderer lurks, eighteen-year-old Magdalena faces recovery from a scandal at her Manhattan private school, schizophrenia, and falling in love with "Wildboy." Told partly through journal entries.