Street Fighter 11: the Origid Warrior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Street Fighter

STREET FIGHTER by Luis Filipe Based on Capcom's videogame "Street Fighter II" Copyright © 2019 This is a fan script [email protected] OVER BLACK. All we hear is the excited CHEER of a crowd. Hundreds of voices roaring in unison, teasing something to come. Under those voices, there is also the rhythmic sound of TRAMPLES on the floor that sound like drums. CUT TO: INT. CORRIDOR - NIGHT A dirty, dimly lit corridor. A few meters ahead, a beam of light leaks through a door that gives access to another scenario. Standing in the corridor hidden in total shadow, a barefoot MAN attired in a white karate gi uniform tightens a black martial arts BELT. We do not see his face. The cheer continues, seeming to be coming from beyond that door in the hallway. After putting on the belt, the man takes a pair of RED GLOVES from his duffel bag, which is on a bench beside him. He wears them calmly. Finally, he also grabs a RED HEADBAND from the bag and ties it around his head. All this is almost ritualistic for him. When completed, the mysterious man walks toward the corridor door where comes the intense light. INT. STREET FIGHTER ARENA - NIGHT A large warehouse-like room. Wooden boxes surround the boundaries of the fighting area. And behind these boxes are the spectators, some sit in stands and others stand on feet. Our mysterious man comes in, revealing his face for the first time: RYU. A Japanese experienced martial artist. The audience goes wild to see him there. -

Adjustment Description Alterations to V-Shift's

Adjustment Description Abilities granting invincibility or armor from the 1st frame, as well as low- risk or high-return moves invincible to throws have all been adjusted to have less effective throw invincibility. Alterations to V-Shift's Considering V-Shift's offensive and defensive capabilities, normal throws offensive/defensive should have enough impact to reliably handle V-Shifts, but characters with capabilities the invincible abilities mentioned above had an easy way to deal with throws and strikes. This gave their defense such a strong advantage that offensive opponents struggled against it. These adjustments seek to correct this issue. These general adjustments are a continuation of previous adjustments. Improvements to While V-Skills and V-Triggers have already been adjusted overall, players infrequently used V-Triggers tend to use one V-Skill and V-Trigger over the other, so we have further and V-Skills strengthened the techniques themselves and the moves that rely on their input. Some characters have been rebalanced in light of previous adjustments. We have buffed characters who were lacking in strength or who were Rebalancing of some largely left alone in previous adjustments. characters Characters with downward adjustments have not had their moves altered significantly; rather, the risks and returns of moves have been properly balanced. Balance Change Overview We've adjusted Nash's close-quarters attack, standing light kick, to yield more of an advantage on hit, and we have further improved Nash's impressive mid to long-distance combat. Standing light kick was previously adjusted to have faster start-up and to be easier to land, but we noticed that it didn't grant the same rewards as it did for other characters. -

Cgcopyright 2013 Alexander Jaffe

c Copyright 2013 Alexander Jaffe Understanding Game Balance with Quantitative Methods Alexander Jaffe A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee: James R. Lee, Chair Zoran Popovi´c,Chair Anna Karlin Program Authorized to Offer Degree: UW Computer Science & Engineering University of Washington Abstract Understanding Game Balance with Quantitative Methods Alexander Jaffe Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Professor James R. Lee CSE Professor Zoran Popovi´c CSE Game balancing is the fine-tuning phase in which a functioning game is adjusted to be deep, fair, and interesting. Balancing is difficult and time-consuming, as designers must repeatedly tweak parameters and run lengthy playtests to evaluate the effects of these changes. Only recently has computer science played a role in balancing, through quantitative balance analysis. Such methods take two forms: analytics for repositories of real gameplay, and the study of simulated players. In this work I rectify a deficiency of prior work: largely ignoring the players themselves. I argue that variety among players is the main source of depth in many games, and that analysis should be contextualized by the behavioral properties of players. Concretely, I present a formalization of diverse forms of game balance. This formulation, called `restricted play', reveals the connection between balancing concerns, by effectively reducing them to the fairness of games with restricted players. Using restricted play as a foundation, I contribute four novel methods of quantitative balance analysis. I first show how game balance be estimated without players, using sim- ulated agents under algorithmic restrictions. -

Black Characters in the Street Fighter Series |Thezonegamer

10/10/2016 Black characters in the Street Fighter series |TheZonegamer LOOKING FOR SOMETHING? HOME ABOUT THEZONEGAMER CONTACT US 1.4k TUESDAY BLACK CHARACTERS IN THE STREET FIGHTER SERIES 16 FEBRUARY 2016 RECENT POSTS On Nintendo and Limited Character Customization Nintendo has often been accused of been stuck in the past and this isn't so far from truth when you... Aug22 2016 | More > Why Sazh deserves a spot in Dissidia Final Fantasy It's been a rocky ride for Sazh Katzroy ever since his debut appearance in Final Fantasy XIII. A... Aug12 2016 | More > Capcom's first Street Fighter game, which was created by Takashi Nishiyama and Hiroshi Tekken 7: Fated Matsumoto made it's way into arcades from around late August of 1987. It would be the Retribution Adds New Character Master Raven first game in which Capcom's golden boy Ryu would make his debut in, but he wouldn't be Fans of the Tekken series the only Street fighter. noticed the absent of black characters in Tekken 7 since the game's... Jul18 2016 | More > "The series's first black character was an African American heavyweight 10 Things You Can Do In boxer." Final Fantasy XV Final Fantasy 15 is at long last free from Square Enix's The story was centred around a martial arts tournament featuring fighters from all over the vault and is releasing this world (five countries to be exact) and had 10 contenders in total, all of whom were non year on... Jun21 2016 | More > playable. Each character had unique and authentic fighting styles but in typical fashion, Mirror's Edge Catalyst: the game's first black character was an African American heavyweight boxer. -

Street Fighter X Tekken Pc Download Street Fighter X Tekken

street fighter x tekken pc download Street Fighter X Tekken. The long awaited dream match-up between the two leaders in the fighting genre becomes a reality. Street Fighter X Tekken delivers the ultimate tag team match up featuring iconic characters from each franchise, and one of the most robust character line ups in fighting game history. With the addition of new gameplay mechanics, the acclaimed fighting engine from Street Fighter IV has been refined to suit the needs of both Street Fighter and Tekken players alike. DREAM MATCH UP � Dozens of playable characters including Hugo, Ibuki, Poison, Dhalsim, Ryu, Ken, Guile, Abel, and Chun-Li from Street Fighter as well as Raven, Kuma, Yoshimitsu, Steve, Kazuya, Nina, King, Marduk, and Bob from Tekken. REAL-TIME TAG BATTLE � Fight as a team of two and switch between characters strategically. FAMILIAR CONTROLS � In Street Fighter X Tekken, controls will feel familiar for fans of both series. JUGGLE SYSTEM � Toss your foes into Tekken-style juggles with Street Fighter X Tekken�s universal air launching system. CROSS ASSAULT � By using the Cross Gauge, a player can activate Cross Assault and attack with both of their characters at the same time. SUPER ART � Using the Cross Gauge you can immediately unleash a Super Art. Ryu�s famed Shinku Hadoken, Kazuya�s Devil Beam as well as the Tekken characters all have original Super Art techniques. ROBUST ONLINE MODES � In addition to the online features from Super Street Fighter IV, Street Fighter X Tekken features totally upgraded online functionality and some new surprises. Game mode: single / multiplayer Multiplayer mode: Internet Player counter: 1-2. -

Metagame Balance

Metagame Balance Alex Jaffe @blinkity Data Scientist, Designer, Programmer Spry Fox 1 Today I’ll be doing a deep dive into one aspect of game balance. It’s the 25-minute lightning talk version of the 800-minute ring cycle talk. I’ll be developing one big idea, so hold on tight! Balance In the fall of 2012, I worked as a technical designer, using data to help balance PlayStation All-Stars Battle Royale, Superbot and Sony Santa Monica’s four- player brawler featuring PS characters from throughout the years. Btw, the game is great, and surprisingly unique, despite its well-known resemblance to that other four-player mascot brawler, Shrek Super Slam. My job was to make sense of the telemetry we gathered and use it to help the designers balance every aspect of the game. What were the impacts of skill, stage, move selection, etc. and what could that tell us about what the game feels like to play? Balance In the fall of 2012, I worked as a technical designer, using data to help balance PlayStation All-Stars Battle Royale, Superbot and Sony Santa Monica’s four- player brawler featuring PS characters from throughout the years. Btw, the game is great, and surprisingly unique, despite its well-known resemblance to that other four-player mascot brawler, Shrek Super Slam. My job was to make sense of the telemetry we gathered and use it to help the designers balance every aspect of the game. What were the impacts of skill, stage, move selection, etc. and what could that tell us about what the game feels like to play? Character Balance There were a lot of big questions about what it’s like to play the game, but at least one pretty quantitative question was paramount: are these characters balanced with respect to one another? I.e. -

4. the Street Fighter Lady

4. The Street Fighter Lady Invisibility and Gender in Game Composition Andy Lemon and Hillegonda C Rietveld Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association December 2019, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 107-133. ISSN 2328-9422 © The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution — NonCommercial –NonDerivative 4.0 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- nd/ 2.5/). IMAGES: All images appearing in this work are property of the respective copyright owners, and are not released into the Creative Commons. The respective owners reserve all rights ABSTRACT The international success of Japanese game design provides an example of the invisibility of female game composers, as well as of gendered identification in game music production and sound design. Yoko Shimomura, the female composer who produced the iconic soundtrack for the 1991 arcade game, Street Fighter II (Capcom 1991), seems to have been invisible to game developers and music producers, which is partly due to the way in which the game is credited as a team effort. Regardless of their personal gender identity, game composers respond to themed briefs by 107 108 The Street Fighter Lady drawing on transnational musical ideas and gendered stereotypes that resonate with the Global Popular. Game music, as imagined as suitable for hyper-masculine game arcades, seems to draw on a masculinist aesthetic developed in Hollywood compositions. In turn, Street Fighter II’s music and the competitive game culture of arcade fighting games has been interwoven with masculinist music scenes of hip-hop and grime. The discussion of the music of Street Fighter II and the musical versions it inspired, nevertheless highlights that although seemingly simplified gendered stereotypes are reproduced within the game, gender identification itself can be complex within the context of game music composition. -

Pots Style Compilation

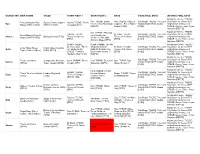

CHARACTER MAIN THEME STAGE STORY FIGHT 1 STORY FIGHT 2 BOSS (FAKE) FINAL BOSS (SECRET) FINAL BOSS Nightmare Geese; THEME: Kyo; THEME: Esaka Ken; THEME: Stage of God Rugal; THEME: The Lord Soy Sauce for Geese [FFS Reinterpretation (Ryu Suzaku Castle (Japan) Akuma THEME: Theme Ryu Forever (Kyo Kusanagi) Capcom - Street Fighter God [CvS2] STAGE: Osaka original/non-arrange ver] Stage) [SSFIIT HDR] [SSFFIIT HDR] of Akuma [SFIV] [KOF97] Remix [CvS2] [CvS2] STAGE: Geese Tower - Inner Sanctum [RBFFS] Nightmare Geese; THEME: Mai; THEME: "Floating" Cammy; THEME: M. Bison; THEME: God Rugal; THEME: The Lord Soy Sauce for Geese [FFS Street Market (Chun-Li on a Fantasy for Chun-Li Beijing (China) [SFA2] Theme of Cammy Theme of M. Bison God [CvS2] STAGE: Osaka original/non-arrange ver] Stage) [SSFIIT HDR] Yvonne Lerolle (Mai [SFIV] [SFIV] [CvS2] STAGE: Geese Tower - Inner Shiranui Stage) [FF3] Sanctum [RBFFS] Charlie; THEME: Rugal; THEME: The ЯR Nightmare Geese; THEME: Decisive Bout - Theme (Rugal Bernstein) M. Bison; THEME: God Rugal; THEME: The Lord Soy Sauce for Geese [FFS Guile Stage [Street Ghost Valley, Nevada Guile of Charlie [SFA3] [KOF98] STAGE: The Theme of M. Bison God [CvS2] STAGE: Osaka original/non-arrange ver] Fighter Tribute Album] (USA) [SFA3] STAGE: Frankfort Black Noah (round 1) [SFIV] [CvS2] STAGE: Geese Tower - Inner Hangar (USA) [SFA3] [KOF94] Sanctum [RBFFS] Nightmare Geese; THEME: God Rugal; THEME: The Lord Soy Sauce for Geese [FFS Theme of Sakura Setagaya-ku Ni-chome, Karin; THEME: Theme Yuri; THEME: Diet (Yuri Ryu; THEME: Ryu -

Company Profile Nov-2003

COMPANYCOMPANY PROFILEPROFILE NOVNOV--20032003 Character Samanosuke by (c)Fu Long Production, (c)CAPCOM CO., LTD. 2004 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Onimusha 3 Market Overview ◆◆ ProspectProspect ofof GameGame MarketMarket ■ Globalization of Game Market ■ Market Projection for Console software (Unit: Millions of Copies) (1) Continuous growth in U.S. and European markets 400 346 350 3313 ① 301 272 Harvest time for software publishers in U.S. market 300 253 242 ② 250 Promising harvest time till CY2005 for software 200 publishers in European market due to late introductions 150 100 50 (2) Moving toward on-line game software market 0 2000 2001 2002 2003E 2004E 2005E ① Establishment of infrastructure for network North America Europe Japan Next-generation environments facilitates on-line gaming ※E: Estimate ※Source: “IDG Report” ② On-line gaming proliferation helps more users to access ■ Market Projection for On-line gaming (Worldwide basis (3) Market expansion through more mobile phone users in the including PC ) (Unit: Millions of U.S. dollars) 600 market 528 478 500 Mobile phone to be another platform for entertainment 408 400 334 games 300 255 (4) Exploitation of the potential markets 200 125 ① Asian market as unexplored market 100 ② 0 Release of console hardware as well as software in 2000 2001E 2002E 2003E 2004E 2005E China ※E: Estimate ※Source: “Trends of Information and Communications Industry” 1 Capcom's position in the video game industry FY2002 Financial Results comparison among the Japanese game software companies. (Unit: 100 Millions of Yen) Nintendo Square Koei Namco Sega Capcom Enix Konami Net Sales 5,041 402 268 1,547 1,972 620 218 2,536 Operating Profit 1,001 125 107 94 92 66 46 -218 of Operating Profit 19.9% 31.3% 40.0% 6.1% 4.7% 10.8% 21.0% -8.6% Net Income 672 140 62 41 30 -195 24 -285 *1. -

Read Book // Street Fighter Classic Volume 3: Psycho Crusher

NPCI2ZH029RT \ eBook / Street Fighter Classic Volume 3: Psycho Crusher (Hardback) Street Figh ter Classic V olume 3: Psych o Crush er (Hardback) Filesize: 7.97 MB Reviews Totally among the best publication I actually have actually go through. It can be filled with wisdom and knowledge Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. (Glen Ernser) DISCLAIMER | DMCA XGJX64Q9TP1R // Book > Street Fighter Classic Volume 3: Psycho Crusher (Hardback) STREET FIGHTER CLASSIC VOLUME 3: PSYCHO CRUSHER (HARDBACK) To save Street Fighter Classic Volume 3: Psycho Crusher (Hardback) eBook, please follow the link listed below and save the file or get access to additional information that are related to STREET FIGHTER CLASSIC VOLUME 3: PSYCHO CRUSHER (HARDBACK) ebook. Udon Entertainment Corp, United States, 2014. Hardback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book. Presenting UDON s classic Street Fighter comics in a gorgeous, oversized hardcover! It s all the pulse-pounding martial arts action of the ultimate fighting game experience, presented through spectacular anime-influenced artwork!In Volume 3, Ryu, Ken, Chun-Li, Guile, Cammy, and more have finally reached the Street Fighter tournament! Some seek revenge, others aim to uncover M.Bison s secrets, while others still are simply looking for a good fight! It s all-out no-holds-barred martial arts action with the fate of the world at stake! Collects Street Fighter II Turbo #1-12. Read Street Fighter Classic Volume 3: Psycho Crusher (Hardback) Online Download PDF Street Fighter Classic Volume 3: Psycho Crusher (Hardback) Download ePUB Street Fighter Classic Volume 3: Psycho Crusher (Hardback) A0QJKNBOE13C \\ Kindle ~ Street Fighter Classic Volume 3: Psycho Crusher (Hardback) You May Also Like [PDF] Johnny Goes to First Grade: Bedtime Stories Book for Children s Age 3-10. -

Dreamcast Fighting

MKII TOURNAMENT ANIMAL CROSSING We continue our Mortal Kombat II CHRONICLES throwdown with the second round of analysis, video and more. Join us as we walk through the days with Samus as she lives her life in the town of Tokyo. PAGE 20 PAGE 37 YEAR 04, NO. 14 Second Quarter 2011 WWW.GAMINGINSURRECTION.COM DREAMCAST FIGHTING GAMES GI SPOTLIGHTS SEGA’S FALLEN VERSUS COMBAT MACHINE contents Columns Features Usual Suspects The Cry of War…....….......….3 Dreamcast fighting games …….4-15 Ready, set, begin ……... 16-19 From the Dungeon…...........3 Mortal Kombat II tournament ..20-24 Retrograde ….………….. 25-28 Beat.Trip.Game. .. .. .. .3 The Strip …....…….…..….29-31 Strip Talk ……………...........29 Online this quarter ….……..32 Otaku ………..…….............30 Retro Game Corner …...34-36 Torture of the Quarter …...36 Animal Crossing Chronicles …………………….….....…37-39 staff this issue Lyndsey Mosley Lyndsey Mosley, an avid video gamer and editor–in-chief journalist, is editor-in-chief of Gaming Insurrection. Mosley wears quite a few hats in the production process of GI: Copy editor, writer, designer, Web designer and photographer. In her spare time, she can be found blogging and watch- ing a few TV shows such as Mad Men, The Guild and Sim- ply Ming. Lyndsey is a copy editor and page designer in the newspaper industry and resides in North Carolina. Editor’s note: As we went to press this quarter, tragedy struck in Japan. Please con- sider donating to the Red Cross to help earthquake and tsunami relief efforts. Thank you from all of the Gaming Insurrection staff. CONTACTCONTACTCONTACT:CONTACT: [email protected] Jamie Mosley is GI’s associate Jamie Mosley GAMING editor. -

Company Profile President's Message

Doc.02 99.9.30 6:31 PM Page H2 1 COMPANY PROFILE PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE A leading company in the amusement have succeeded in producing one hit after advertising and incentive-based consumer industry, Capcom develops, publishes and another, and the release of Resident Evil in promotions such as our innovative Fighters Edge program. distributes a variety of software games for March 1996 established a new genre, both arcade machines and home video "Survival Horror", which is unrivaled by our With the new millennium on the horizon, the business consoles. We also operate amusement competitors. Popular all over the world, the world is on the brink of change. We are entering an age where consumers will have the power of choice. facilities at 47 locations in Japan. Since the outstanding Resident Evil series has Bidding farewell to mass consumption, we will see foundation of the company in May 1979, we contributed enormously to Capcom's growth. the development of an information-centered society have taken a leading role in the entertainment In addition to our existing overseas which contributes to a higher level of customer software industry and have continued to subsidiaries in the United States and Asia, we satisfaction as well as increased environmental awareness. And in the years to come, the world will respond to the demand and expectations of established Capcom Eurosoft in London, continue to change at a faster rate than ever. customers. In March 1991, we achieved the England in July 1998, as a main sales base for top position in the arcade game industry with the European home video game market.