Encounters and Engagements Between Economic and Cultural Geography the Geojournal Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

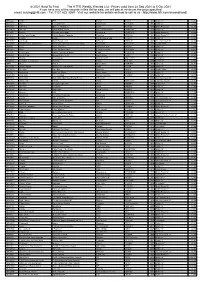

2021 Hard to Find the HTFR Weekly Wanted List

© 2021 Hard To Find The HTFR Weekly Wanted List - Prices valid from 28 Sep 2021 to 5 Oct 2021 If you have any of the records in this list for sale, we will pay at minimum the price specified email: [email protected] - Tel: 0121 622 3269 - Visit our website for details on how to sell to us - http://www.htfr.com/secondhand/ MR26666 100Hz EP3 Pacific FIC020 1999 British 12" £4.00 MR75274 16B Trail Of Dreams Stonehouse STR12008 1995 British 12" £2.00 MR18837 2 Funky 2 Brothers And Sisters Logic FUNKY2 1994 British Promo 12" £2.00 MR759025 3rd Core Mindless And Broken WEA International Inc. SAM00291 2000 British 12" £2.00 MR12656 4 Hero Cooking Up Ya Brain Reinforced RIVET1216 1992 British Promo 12" £2.00 MR14089 A Guy Called Gerald 28 Gun Badboy / Paranoia Columbia XPR1684 1992 British Promo 12" £8.00 MR169958 A Sides Punks Strictly Underground STUR74 1996 British 12" £4.00 MR353153 Aaron Carl Down (Resurrected) Wallshaker WMAC30 2009 American Import 12" £2.00 MR759966 Academy Of St. Martin-in-the-F Amadeus (Original Soundtrack Recording) Metronome 8251261ME 1984 Double Album £2.00 MR4926 Acen Close Your Eyes Production House PNT034 1992 British 12" £3.00 MR12863 Acen Trip Ii The Moon Part 3 Production House PNT042RX 1992 British 12" £3.00 MR16291 Age Of Love Age Of Love (Jam & Spoon) React 12REACT9 1992 British 12" £7.00 MR44954 Agent Orange Sounds Flakey To Me Agent Orange AO001 1992 British 12" £8.00 MR764680 Akasha Cinematique Wall Of Sound WALLLP016 1998 Vinyl Album £1.00 MR42023 Alan Braxe & Fred Falke Running Vulture VULT001 2000 French -

DEQ No.10 Interactive

Letter from the publisher: DEQ #10 I hate to be negative in such a positive publication, but ity, but instead I saw gaping mouths and sad faces. I found when the bubble goes pop! And the air comes out… we myself staring at the cover of the 12” record with Brown need to talk. in a fancy suit and Apollo Creed (actor Carl Weathers) in his red, white and blue satin boxing outfit. “How does it When was your personal bubble last broken? Was it a feel when there’s no destination too far?” Brown belted out. “friend” that stabbed you in the back? Was it a bad break “And somewhere on the way you might find who you are!” I up? Was it the death of a loved one? Whatever the situa- guess I never paid attention to the words until that moment. tion, it hurts. You scatter to regroup from the unthinkable. The gut wrenching pain deepens grooves in your brain and I thought about my life’s journey and about how much bet- brings you to your forever changed mental map. We can ter of a person I am through friendships with people from repair and reinflate the bubble, and it might look different, other cultures. Putting this magazine together and playing but ultimately it’s our address. nights with diverse people make me realize how truly lucky I am (and I’m sure you do as well.) Steven Reaume said so It’s easier than ever now to get consumed in our own lives. profoundly in his article, “When you risk everything to do We can have so much of what we want, when we want and what you love, it’s worth every bit.” the way we want it. -

Ambient Music the Complete Guide

Ambient music The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 05 Dec 2011 00:43:32 UTC Contents Articles Ambient music 1 Stylistic origins 9 20th-century classical music 9 Electronic music 17 Minimal music 39 Psychedelic rock 48 Krautrock 59 Space rock 64 New Age music 67 Typical instruments 71 Electronic musical instrument 71 Electroacoustic music 84 Folk instrument 90 Derivative forms 93 Ambient house 93 Lounge music 96 Chill-out music 99 Downtempo 101 Subgenres 103 Dark ambient 103 Drone music 105 Lowercase 115 Detroit techno 116 Fusion genres 122 Illbient 122 Psybient 124 Space music 128 Related topics and lists 138 List of ambient artists 138 List of electronic music genres 147 Furniture music 153 References Article Sources and Contributors 156 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 160 Article Licenses License 162 Ambient music 1 Ambient music Ambient music Stylistic origins Electronic art music Minimalist music [1] Drone music Psychedelic rock Krautrock Space rock Frippertronics Cultural origins Early 1970s, United Kingdom Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments, electroacoustic music instruments, and any other instruments or sounds (including world instruments) with electronic processing Mainstream Low popularity Derivative forms Ambient house – Ambient techno – Chillout – Downtempo – Trance – Intelligent dance Subgenres [1] Dark ambient – Drone music – Lowercase – Black ambient – Detroit techno – Shoegaze Fusion genres Ambient dub – Illbient – Psybient – Ambient industrial – Ambient house – Space music – Post-rock Other topics Ambient music artists – List of electronic music genres – Furniture music Ambient music is a musical genre that focuses largely on the timbral characteristics of sounds, often organized or performed to evoke an "atmospheric",[2] "visual"[3] or "unobtrusive" quality. -

Detroit – Berlin: One Circle Music • Talk • Performance • Installation • Film • Club 30.5.–2.6

HAU Detroit – Be rl in: One Circle 30.5. –2.6.2 01 8 Detroit – Berlin: One Circle Music • Talk • Performance • Installation • Film • Club 30.5.–2.6. / HAU1, HAU2, HAU3, Outdoor, Tresor Berlin “Detroit – Berlin: One Circle” spürt der in - Mit Olad Aden ten siven Beziehung zweier immer wieder Joshua Akers abgeschriebener und doch symbolisch Yuko Asanuma A.W.A. überfrachteter Orte nach. Zentren, die mit Mike Banks den sofort assoziierten Bildern brach lie - Lisa Blanning Halima Cassells / Free Market of Detroit gender Zivilisationsruinen einen fast my - Ché & DJ Stacyé J thologischen Austeritäts-(Anti-)Glamour John E. Collins Bryce Detroit versprühen. Zwei Städte aber vor allem, Tashy Endres die im popkulturellen Bewusstsein seit Mark Ernestus den 1980er-Jahren untrennbar durch die Eddie Fowlkes Philipp Halver rasante Entwicklung und Verbreitung von Cornelius Harris Techno miteinander verbunden sind. “De - Dimitri Hegemann Mike Huckaby troit – Berlin: One Circle”, das sich mit sei - Ford Kelly nem Titel auf Robert Hoods Track “Detroit: Kotti-Shop / SuperFuture (Julia Brunner, Stefan Endewardt) One Circle” bezieht, ist das Produkt einer Ingrid LaFleur kooperativen Zusammenarbeit mit ganz Lakuti Séverine Marguin unterschiedlichen, zumeist sub- und pop - Maryisonacid kulturell informierten Akteur *innen, aber Tiff Massey Diana McCarty auch mit Aktivist*innen von (Grassroots-) Zoë Claire Miller Bewegungen, die durch das Engagement Miz Korona & The Korona Effect MODEL 500 (Juan Atkins, Mark Taylor, von African Americans ge prägt werden, Milton Baldwin & Gerald Brunson) die die Bevölkerungsmehrheit Detroits Nguy ễn Baly Kerstin Niemann aus machen. Lucas Pohl SDW e.V. (Frieder Blume, Elisabeth Inhalt Ein Festival des HAU Hebbel am Ufer. Gefördert im Rahmen des Bündnisses internatio - naler Produktionshäuser von der Beauftragten der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Me - Hampe, Anta Helena Recke, Joana “(Anti-)Glamour” von Zuri Maria Daiß, Pascal Jurt und Sarah Reimann 5 dien. -

Doctor of Philosophy

RICE UNIVERSITY By tommy symmes A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy APPROVED, THESIS COMMITTEE William B Parsons William B Parsons (Apr 21, 2021 11:48 PDT) William Parsons Jeffrey Kripal Jeffrey Kripal (Apr 21, 2021 13:45 CDT) Jeffrey Kripal James Faubion James Faubion (Apr 21, 2021 14:17 CDT) James Faubion HOUSTON, TEXAS April 2021 1 Abstract This dissertation studies dance music events in a field survey of writings, in field work with interviews, and in conversations between material of interest sourced from the writing and interviews. Conversations are arranged around six reading themes: events, ineffability, dancing, the materiality of sound, critique, and darkness. The field survey searches for these themes in histories, sociotheoretical studies, memoirs, musical nonfiction, and zines. The field work searches for these themes at six dance music event series in the Twin Cities: Warehouse 1, Freak Of The Week, House Proud, Techno Tuesday, Communion, and the Headspace Collective. The dissertation learns that conversations that take place at dance music events often reflect and engage with multiple of the same themes as conversations that take place in writings about dance music events. So this dissertation suggests that writings about dance music events would always do well to listen closely to what people at dance music events are already chatting about, because conversations about dance music events are also, often enough, conversations about things besides dance music events as well. 2 Acknowledgments Thanks to my dissertation committee for reading this dissertation and patiently indulging me in conversations about dance music events. -

Bush Visits Delaware

An Associated Collegiate Press Pacemaker Award Winner FRIDAY January 14, 2000 • Volume 126 THE • Number 24 Review Online Non-Profit Org. www. review. utlel. edu U.S. Postage Paid Newark, DE Permit No. 26 250 Student Center • University ofDela~are • Newark, DE 19716 FREE UD professor Bush visits goes 7,800 ft. Delaware BY JOHN YOCCA "realistic and makes sense." under the sea Natinna i!Stare Nelt'S Ediror He said he believes that to make WILMINGTON - Republican sure the economy continues to grow. presidential candidate Texas Gov. it is important to cut marginal rates BY PAUL MATHEWS Geo rge W. Bus h made an foreverytaxpayerinAmerica. Administrati1·e News Ediwr appearance at a D e laware McCain ha recently called for a Associate professor Craig Cary talked with area students . Republican Party fundra iser middle-class tax cut of S237 billion, from a mile and a half below the surface of the water off the Wednesday to discuss hi campaign. half the size of Bush's. McCain also coast of Mexico Thursday in the world's first deep-sea dive Bush , speaking to a crowd of said he would set aside $231 billion of the new millennium. m ore than 200 suppo rters in the of expected budget surpluses for the The dive in the Sea of Cones, touted as "Extreme 2000: Hotel DuPont, outlined his platform Social Security program over five Voyage to the Deep," included a conference call with area and asked for s uppo rt from years. schools from the sea floor. Delawareans. F or lower incom e taxpaye rs , Tracey Bryant, marine outreach coordinator at the ''I'm interested in m aking sure Bush a id, he would lower the university, said seven Delaware high schools and this party is vibrant, whole and bottom tax rate from 15 percent to intermediate schools, along with two other schools in exciting," he said. -

The Body and Technology in Popular Culture

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2004 The Body and Technology in Popular Culture Przemyslaw Psuj Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Recommended Citation Psuj, P. (2004). The Body and Technology in Popular Culture. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/955 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/955 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. .. The Body and Technology in Popular Culture Przemyslaw Psuj Bachelor of Arts in English with Honours School of International Cultural and Community Studies Edith Cowan University 11 August 2004 USE OF THESIS The Use of Thesis statement is not included in this version of the thesis. 2 ABSTRACT: The human experience of the world today is increasingly adapted and understood via technological terms and systems. -

Ministério Da Cidadania, Itaú, Secretaria Municipal De Cultura E Sesc Apresentam

MINISTÉRIO DA CIDADANIA, ITAÚ, SECRETARIA MUNICIPAL DE CULTURA E SESC APRESENTAM cartografas.mitsp_07 2020 Revista de Artes Cênicas Número 7 - 2020 ISSN 2357-7487 Mostra Internacional de Teatro de São Paulo / MITsp Departamento de Artes Cênicas da ECA-USP Programa de Pós-Graduação em Artes Cênicas da ECA-USP Periodicidade anual Escola de Comunicações e Artes Av. Prof. Lúcio Martins Rodrigues, 443 Cidade Universitária - São Paulo - SP EDITORAS RESPONSÁVEIS Daniele Avila Small, Luciana Eastwood Romagnolli e Sílvia Fernandes COMISSÃO EDITORIAL Antonio Araujo e Maria Fernanda Vomero EDITORA-EXECUTIVA Maria Luísa Barsanelli EDITORA-ASSISTENTE Mariana Marinho IDENTIDADE VISUAL E PROJETO GRÁFICO Casaplanta + Lila Botter REVISÃO Grená Conteúdo Multiplataforma SUMÁRIO 8 Apresentação MITsp | Espetáculos internacionais 12 Ao Terceiro Sinal 34 Entrevista com Tiago Rodrigues 40 By Heart x 14 Insurgência em tempos de escassez 44 Sopro 16 Cena Brasileira: uma paisagem 48 Pelo prazer de pensar e fazer pensar de corpos insubordinados por Maria João Brilhante 18 A quem se interessar 54 Burgerz 58 As simples e importantes perguntas 20 Que se implodam as estruturas por Renan Ji 22 Encontra de pedagogias da teatra: 62 Contos Imorais – Parte 1: Casa Mãe aFetividades do saber riscar e arriscar 66 Quando as ruínas falam 24 Parceiros por Clóvis Domingos dos Santos 70 Farm Fatale 74 A utopia que nasce do feio por Rodrigo Nascimento 78 Multidão [Crowd] 82 Jerk [Babaca] 86 Estranhos (quase) familiares por Michele Bicca Rolim 92 O Pedido 96 O Pedido e o muro sonoro -

Dancing in the Technoculture Hillegonda C Rietveld

Dancing in the Technoculture Hillegonda C Rietveld To be published in: Simon Emmerson (Ed)(2018) The Routledge Research Companion To Electronic Music: Reaching Out With Technology. London and New York: Routledge Abstract This chapter will address a transnational network of relationships within electronic dance music in the context of the machine aesthetic of techno. It will be shown that a sense of a global music scene is nevertheless possible. Beyond historically shaped post-colonial and socio-economic links that underpin a range of global popular cultural forms, the techno aesthetic arguably responds to, and inoculates against, a sense of post-human alienation and a dominance of electronic communication and information technologies of the technoculture. Accompanied by a form of futurism, techno scenes embrace the radical potential of information technologies in a seemingly deterritorialised manner, producing locally specific responses to the global technoculture that can differ in aesthetics and identity politics. In this sense, the electronic dance music floor embodies a plurality of competing “technocracies”. Introduction This chapter addresses transnational, yet locally definable, electronic dance music culture as it engages with and intervenes globalising experiences of urbanised life, and the digitally networked information and communication technologies that characterise and dominate what is currently know as “the technoculture” (Shaw, 2008; Robins and Webster, 1999; Constance and Ross, 1991). Electronic dance music, as it developed -

Rolando - the Ransom Note Mix $ Soundcloud

LINKS # Facebook ! Twitter " Instagram PRESS $ SoundCloud ROLAND ROCHA RECORDS # Facebook Rolando - The Ransom Note Mix $ SoundCloud RIDER 2 x Technics 1210 mk 5g turntables (or 1210mk2) My Favourite Record: DJ Rolando 3 x Pioneer CDJ-2000 NEXUS (linked) 1 x Pioneer DJM-900 ALLEN & HEATH MIXERS NOT ACCEPTABLE BOOKING INQUIRIES Age Of The Jaguar: 5 Steps With DJ Rolando Nicole Palacio Los Angeles, California [email protected] DJ Rolando on Leaving Underground Resistance and Life After Detroit BIO legendary producer and DJ at the forefront of techno, A Rolando’s career spanning nearly 30 years is a testament of timeless talent. Growing up in a Hispanic district in southwest Detroit, Rolando was heavily influenced by his cultural Latin rhythms and percussion. Inspired from an early age by his musician father, he pursued his own interest in music, later discovering the innovative sounds of techno once he heard Jeff Mills in 1985 as "The Wizard". Through a mutual friend, he was introduced to Mike Banks and joined Underground Resistance in 1994. Although not his first release on UR, 1999’s 'Jaguar' turned perceptions of Techno on their head, breaking into other genres of dance music and becoming a classic in the boxes of DJs such as Tenaglia, Morillo, Oakenfold, and Gilles Peterson. The track has a long legacy of reworking and lives on fifteen years later inspiring audiences from all genres. From there, found the Los Hermanos project with Gerald Mitchell while touring the world as a respected solo DJ and community leader. As of November 2004, Rolando left both Underground Resistance and his Los Hermanos project behind to pursue solo work. -

Regular/Slanted/Ultra/Ultra Slanted

Blak Blak Blak Blak Blak Regular/Slanted/Ultra/Ultra Slanted © extratype, all rights reserved. Available from ≥ extratype.com Blak | Regular Transmat Metroplex Electro Cybotron Frankie Knuckles Electrifying Ron Hardy Mojo © extratype, all rights reserved. Available from ≥ extratype.com Blak | Regular Italic DJ Rolando Scan 7 Drexciya Jay Denham Aril Brikha Teknotika Black Nation Richard Davis © extratype, all rights reserved. Available from ≥ extratype.com Blak | Ultra P-funk Jeff Mills Aux 88 Kelli Hand Detroit Eddie Fowlkes Washte- naw © extratype, all rights reserved. Available from ≥ extratype.com Blak | Ultra Italic Juan Atkins Belleville Three! Derrick May Frankie Knuckles 1981 © extratype, all rights reserved. Available from ≥ extratype.com Blak Regular The Quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog & Handgloves 02!? Italic The Quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog & Handgloves 02!? Ultra The Quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog & Handgloves 02!? Ultra Italic The Quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog & Handgloves 02!? © extratype, all rights reserved. Available from ≥ extratype.com Blak Regular 24/30 Detroit techno es un estilo de música electrónica que nació al comienzo de los años 1980. Detroit está considerado el lugar de nacimiento del techno. Los artistas de Detroit techno más importantes son Juan Atkins, Derrick May y Kevin Saunderson. Son rasgos distintivos del Detroit techno el uso de sintetizadores analógicos y cajas de ritmos. Regular Italic 24/30 Detroit techno es un estilo de música electrónica que nació al comienzo de los años 1980. Detroit está considerado el lugar de nacimiento del techno. Los artistas de Detroit techno más importantes son Juan Atkins, Derrick May y Kevin Saunderson. -

Juhlaviikot #Helsinkifestival Gisèle Vienne

#juhlaviikot #helsinkifestival The visit is produced in collaboration with Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation © Estelle Hanania and Dance House Helsinki. Gisèle Vienne CROWD Pääyhteistyökumppanit / Partners / Partners Sponsorit / Sponsors / Sponsorer Thu–Sat 29.–31.8. Finnish National Opera, Almi Hall CROWD New Production 2017 Conception, choreography and scenography Gisèle Vienne Assisted by Anja Röttgerkamp and Nuria Guiu Sagarra Lights Patrick Riou Dramaturgy Gisèle Vienne and Denis Cooper Music selections from Underground Resistance, KTL, Vapour Space, DJ Rolando, Drexciya, The Martian, Choice, Jeff Mills, Peter Rehberg, Manuel Göttsching, Sun Electric and Global Communication Edits, playlist selection Peter Rehberg Sound diffusion supervisor Stephen O’Malley Performers Philip Berlin, Marine Chesnais, Georges Labbat, Sylvain Decloitre, Sophie Demeyer, Vincent Dupuy, Massimo Fusco, Gisèle Vienne CROWD Rémi Hollant, Oskar Landström, Theo Livesey, Louise Perming, Katia Petrowick, Jonathan Schatz, Henrietta Wallberg and Tyra Wigg New production 2017 Costumes Gisèle Vienne in collaboration with Camille Queval and the performers Sound engineer Adrien Michel Premiere November 8,9 & 10th at Maillon, Théâtre de Strasbourg – Scène européenne in Technical manager Richard Pierre partnership with POLESUD, CDCN Strasbourg Stage manager Antoine Hordé The Company Gisèle Vienne is supported by Ministère de la culture et de la Light manager Arnaud Lavisse communication – DRAC Grand Est, la Région Grand Est and Ville de Strasbourg. Special thanks Margret