Keeping Cajun Music Alive – “Yes, Siree, I Guarontee Ya”: a Conversation with Pe-Te Johnson and Jason Theriot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression

American Music in the 20th Century 6 Chapter 2 Music in the United States Before the Great Depression Background: The United States in 1900-1929 In 1920 in the US - Average annual income = $1,100 - Average purchase price of a house = $4,000 - A year's tuition at Harvard University = $200 - Average price of a car = $600 - A gallon of gas = 20 cents - A loaf of Bread = 20 cents Between 1900 and the October 1929 stock market crash that triggered the Great Depression, the United States population grew By 47 million citizens (from 76 million to 123 million). Guided by the vision of presidents Theodore Roosevelt1 and William Taft,2 the US 1) began exerting greater political influence in North America and the Caribbean.3 2) completed the Panama Canal4—making it much faster and cheaper to ship its goods around the world. 3) entered its "Progressive Era" by a) passing anti-trust laws to Break up corporate monopolies, b) abolishing child labor in favor of federally-funded puBlic education, and c) initiating the first federal oversight of food and drug quality. 4) grew to 48 states coast-to-coast (1912). 5) ratified the 16th Amendment—estaBlishing a federal income tax (1913). In addition, by 1901, the Lucas brothers had developed a reliaBle process to extract crude oil from underground, which soon massively increased the worldwide supply of oil while significantly lowering its price. This turned the US into the leader of the new energy technology for the next 60 years, and opened the possibility for numerous new oil-reliant inventions. -

The Promulgator the Official Magazine of the Lafayette Bar Association

THE PROMULGATOR The Official Magazine of the Lafayette Bar Association DON’T FORGET: RENEW 2018 DUES 2018 lba president donnie o’pry december 2017 | volume 40 | issue 6 page 2 Officers Donnie O’Pry President Maggie Simar OUR MISSION is to serve the profession, its members and the President-Elect community by promoting professional excellence, respect for the rule of law and fellowship among attorneys and the court. Theodore Glenn Edwards Secretary/Treasurer THE PROMULGATOR is the official magazine of the Lafayette Bar Association, and is published six times per year. The opinions expressed Missy Theriot herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the Editorial Committee. Imm. Past President ON THE COVER Board Members This issue of the Promulgator introduces 2018 Neal Angelle Kyle Bacon Lafayette Bar Association President Donovan Bart Bernard “Donnie” O’Pry II. Our cover photo features Shannon Dartez Donnie’s family. Get to know Donnie on page 10. Franchesca Hamilton-Acker Scott Higgins William Keaty II Karen King Cliff LaCour Pat Magee Matthew McConnell Dawn Morris TABLE OF CONTENTS UPCOMING EVENTS Joe Oelkers President's Message ..........................................................4 Keith Saltzman Executive Director’s Message .....................................5 DECEMBER 07 LBA Holiday Party William Stagg Family Law Section ............................................................7 LBA @ 5:30 p.m. Lindsay Meador Young Young Lawyers Section ...................................................8 Off the Beaten Path: Justin Leger -

Musical Traditions of Southern Louisiana

Musical Traditions of Southern Louisiana Rosalon Moorhead GENERAL INTRODUCTION This unit was developed for use in French classes at the secondary level. It gives students opportunities to Research the history and patterns of French settlement in Louisiana Discover three types of music (New Orleans jazz, Cajun, Zydeco) which are representative of the Francophone presence in Louisiana. Make connections between the rhythms of the music and those of the French language. Although I intend to use the unit in my fourth-year French classes at Bellaire High School, the material is probably better suited to the curriculum of second- or third-year classes, as some of the state-adopted textbooks at those levels have chapters that deal with Louisiana. I believe that the unit could be modified for use at any level of French language instruction. BACKGROUND NARRATIVE In the nearly twenty years that I have been teaching French, I have observed that while the students‟ motivations to take the class have remained largely the same (it‟s a beautiful language, I want to travel/live in France, my mother made me), the emphases in the teaching of the language have changed quite a bit. As a student and in the early years of my teaching career, I (along with other Americans) studied the sound system and patterns of the language, attempting to mimic the pronunciation and intonation of French as my primary goal. That approach was superseded variously by those focusing on the grammar, the vocabulary, or the learning of language in context as revealed by reading. The one aspect of the study of French that seemed to be static was the culture; until very recently, the references were to France, and more specifically, to Paris. -

Found Poem - Found Song

Louisiana Voices Folklife in Education Project www.louisianavoices.org Unit VI Louisiana's Musical Landscape Lessons 1 and 2 Found Poem - Found Song Name Date TOPIC: Louisiana_Music TASK: A Found Poem is made with words and phrases from something you read. It uses someone else’s language, but the poet combines it in a new way. Write a Found Poem following these directions. 1. Your teacher will assign one of these articles for you to read: • The Treasured Traditions of Louisiana Music, by Ben Sandmel • Cajun Music: Alive and Well in Louisiana, by Ann Savoy • Cajun Music as Oral Poetry, by Carolyn Ware • Hayride Boogie: Blues, Rockabilly and Soul from the Louisiana Hill and Delta Country, by Mike Luster • North Louisiana String Band, by Susan Roach • Since Ol’ Gabriel’s Time: Hezekiah and the Houserockers, by David Evans 2. As you read, choose ten main key words or phrases that give the meaning of that music genre to you, and jot them down. 3. Arrange these words or phrases in a pleasing and meaningful way to make a poem. 4. Write or type the poem and illustrate it with drawings or pictures you have collected for this lesson. 5. Read or recite your poem to the class. 6. Work with your group to choose a song in the genre you have read about, then arrange words and phrases to make a song about the genre. Use the Tempo, Dynamics, and Rhythm that are unique to the genre. If possible, locate some of the instruments used in that genre to accompany the singing. -

History of Blues

MU 012 D1 SL: Music and Culture in New Orleans Spring 2020 Course Syllabus Instructor: Clyde Stats Phone: 238-1730 (cell) email – [email protected] Course Meets: Hybrid – online plus 4 required in-class meetings – 1/21; 3/4; 3/24; 4/14; 7:00 – 9:30 p.m. Location: Lafayette L202 Required Text - Rose, Chris. 1 Dead in Attic; (available from instructor) Other excerpts (available online) from: The World That Made New Orleans by Ned Sublette Keeping the Beat on the Street by Nick Burns The Civically Engaged Reader by Davis & Lynn New Directions for Teaching and Learning by R. Rhoads Essential Jazz: The First 100 Years by Martin and Waters Musical Gumbo: The Music of New Orleans by Grace Lichtenstein Cajun Music Vol. I by Ann Allen Savoy Websites: Louisiana Folk Regions Map: http://www.louisianavoices.org/Unit4/edu_unit4_3subregions.html The Treasured Traditions of Louisiana Music: http://www.louisianafolklife.org/LT/Articles_Essays/treas_trad_la_music.html A Brief History of New Orleans Jazz: http://www.nps.gov/archive/jazz/Jazz%20History_origins_pre1895.htm History of Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs: http://www.mardigrasdigest.com/Sec_2ndline/2ndline_history.htm History of Mardi Gras: http://www.eastjeffersonparish.com/culture/MARDIGRA/HISTORY/history.htm History of Mardi Gras Indians: http://www.mardigrasindians.com/ Origins of Cajun and Zydeco Music: http://www.scn.org/zydeco/nwczHISTORY.htm Hurricane Katrina Timeline: http://www.nola.com/katrina/timeline/ Required Listening – Various examples posted online Videos Vulnerable New Orleans: -

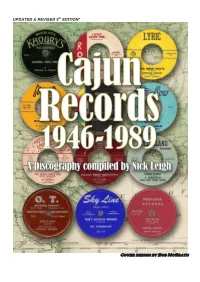

UPDATED & REVISED 5 EDITION* Cover Design by Bob Mcgrath

UPDATED & REVISED 5th EDITION* Cover design by Bob McGrath CAJUN RECORDS 1946-1989 – A DISCOGRAPHY © Nick Leigh 2019 INTRODUCTION TO THE REVISED EDITIONS I began collecting blues records in 1959 but it was another 7 years before I heard Cleveland Crochet & the Sugar Bees on the Storyville anthology “Louisiana Blues”. My appetite whetted, I wanted more. Buying the Iry Le Jeune LPs on Goldband a few months later (not one but two volumes – and purchased as imports on a student’s allowance!) fuelled an appreciation of Cajun music that has remained undiminished. In the mid 1960s, however, there was little information available about the great music I was listening to, other than the catalogues I obtained from Goldband and Swallow, and the early articles by Mike Leadbitter and John Broven in “Blues Unlimited” and “Jazz Journal”. Thanks to people like Mike, John, Neil Slaven, Rob Ford and Les Fancourt there is now a lot of information available to provide the background to blues and rhythm & blues recordings. However much of the information about the post World War 2 music of South Louisiana in general and the French (Cajun) recordings in particular, remains elusive. So far as I know no single ‘discography’ of post-war Cajun record releases has been published and I thought I would try to correct this oversight. This is notwithstanding the increasing amount of well researched material about the music in general and individual artists. Therefore I take only limited credit for the information included herein about the recordings. My aim has been to bring that material together in a single document. -

Accordion (Music Playing) Narrator: Along with the Argentinean Tango

Accordion (Music playing) Narrator: Along with the Argentinean tango, French musettes, and German polkas, the accordion is one of the defining sounds of Central Texas conjunto bands, as well as Southeast Texas Cajun and zydeco music, country, and western swing. (Music playing) N: With its roots dating back to China thousands of years ago, the popularity of this instrument took off in the early nineteenth century in Europe. N: By the mid 1800s, immigrants had brought the accordion to Texas, where it became emblematic in the way different ethnic groups have shared their musical heritage and influences. (Music playing) N: Patented in 1829 by an Austrian named Cyrill Demian, the accordion spread quickly throughout Europe. N: From Ireland to Russia, versatility and sheer volume of this instrument attracted folk musicians who adapted it to their own style of music. N: However, it was the Germans, Czechs, and French who forever changed Texas music with their use of the accordion. (Music playing) N: German immigrants began moving to Central Texas in large numbers in the 1840s, settling in what became known as the “German Belt,”areas including New Braunfels, Fredericksburg, and Luckenbach. N: German folk songs, with the polka, waltz, and schottische dance steps, were a fundamental part of these immigrant communities, and the accordion was essential to their music. (Music playing) N: By the turn-of-the-century, German Texans and Tejanos were increasingly exchanging musical influences. N: Santiago Jiménez began playing the accordion in 1921 at the age of eight. N: His father, Patricio, had been a successful accordion player in Eagle Pass, Texas, and he encouraged his son to play. -

The Music of Louisiana: Cajuns, Creoles and Zydeco

The Music of Louisiana: Cajuns, Creoles and Zydeco Carole Poindexter-Sylvers INTRODUCTION The music and cuisine of southern Louisiana experienced a renaissance during the 1980s. Zydeco musicians and recording artists made appearances on morning talk shows, Cajun and Creole restaurants began to spring up across the nation, and celebrity chefs such Paul Prudhomme served as a catalyst for the surge in interest. What was once unknown by the majority of Americans and marginalized within the non-French speaking community in Louisiana had now become a national trend. The Acadians, originally from Acadia, Nova Scotia, were expelled from Canada and gradually became known as Cajuns. These Acadians or Cajuns proudly began teaching the lingua franca in their francophone communities as Cajun French, published children‘s books in Cajun French and school curricula in Cajun French. Courses were offered at local universities in Cajun studies and Cajun professors published scholarly works about Cajuns. Essentially, the once marginalized peasants had become legitimized. Cajuns as a people, as a culture, and as a discipline were deemed worthy of academic study stimulating even more interest. The Creoles of color (referring to light-skinned, French-speaking Negroid people born in Louisiana or the French West Indies), on the other hand, were not acknowledged to the same degree as the Cajuns for their autonomy. It would probably be safe to assume that many people outside of the state of Louisiana do not know that there is a difference between Cajuns and Creoles – that they are a homogeneous ethnic or cultural group. Creoles of color and Louisiana Afro-Francophones have been lumped together with African American culture and folkways or southern folk culture. -

MIO ANN SAVOY PLAYLIST Dans La Louisiane Savoy

MIO ANN SAVOY PLAYLIST Getting Some Fun Out of Life Ann Savoy & Her Sleepless Knights CD: If Dreams Come True Si J’aurais Des Ailes Ann Savoy & Joel Savoy CD: Allons Boire un Coup: A collection of Cajun and Creole Drinking Songs Dans La Louisiane Savoy-Doucet Cajun Band CD: Live! At the Dance It's Like Reaching for the Moon Ann Savoy & Her Sleepless Knights CD: If Dreams Come True I Can’t Get Over You Ann Savoy (Live) At the Jazz Band Ball Pete Fountain and Al Hirt CD: New Orleans Jazz A Foggy Day Frank Sinatra CD: Songs for Young Lovers If You Were Mine Billie Holiday CD: The Essential Billie Holiday If I Had My Way Peter Paul and Mary CD: Peter Paul and Mary in Japan Fantasie D'Amour Loudovic Bource CD: The Artist (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) Cathy’s Theme Wuthering Heights Original Trailer, 1959 YouTube I Made a Big Mistake Ann & Marc Savoy CD: J’ai ete au bal Happy One Step Savoy-Doucet Cajun Band CD: The Best of the Savoy-Doucet Cajun Band Happy One Step Dennis McGee CD: The Complete Early Recordings of Dennis McGee Devillier Two Step Dennis McGee and Sady Courville La Vieille Musique Acadienne Lafayette Cleoma Breaux & Joe Falcon CD: Cajun Music Mon Coeur T’appelle Cleoma Breaux CD: Cajun Dance Party: Fais Do-Do Valse de Opelousas Amede Ardoin CD: Mama I’ll Be Long Gone: The Complete Recordings of Amede Ardoin 1929-1934 Muskrat Ramble Lawrence Welk Show, 1955 YouTube Aux Illinois Ann Savoy CD: I Wanna Sing Right: Rediscovering Lomax in the Evangeline Country Nuages Ann Savoy and Her Sleepless Knights CD: Black Coffee Embraceable You Ann Savoy and Her Sleepless Knights, feat. -

Music Genre/Form Terms in LCGFT Derivative Works

Music Genre/Form Terms in LCGFT Derivative works … Adaptations Arrangements (Music) Intabulations Piano scores Simplified editions (Music) Vocal scores Excerpts Facsimiles … Illustrated works … Fingering charts … Posters Playbills (Posters) Toy and movable books … Sound books … Informational works … Fingering charts … Posters Playbills (Posters) Press releases Programs (Publications) Concert programs Dance programs Film festival programs Memorial service programs Opera programs Theater programs … Reference works Catalogs … Discographies ... Thematic catalogs (Music) … Reviews Book reviews Dance reviews Motion picture reviews Music reviews Television program reviews Theater reviews Instructional and educational works Teaching pieces (Music) Methods (Music) Studies (Music) Music Accompaniments (Music) Recorded accompaniments Karaoke Arrangements (Music) Intabulations Piano scores Simplified editions (Music) Vocal scores Art music Aʼak Aleatory music Open form music Anthems Ballades (Instrumental music) Barcaroles Cadenzas Canons (Music) Rounds (Music) Cantatas Carnatic music Ālāpa Chamber music Part songs Balletti (Part songs) Cacce (Part songs) Canti carnascialeschi Canzonets (Part songs) Ensaladas Madrigals (Music) Motets Rounds (Music) Villotte Chorale preludes Concert etudes Concertos Concerti grossi Dastgāhs Dialogues (Music) Fanfares Finales (Music) Fugues Gagaku Bugaku (Music) Saibara Hát ả đào Hát bội Heike biwa Hindustani music Dādrās Dhrupad Dhuns Gats (Music) Khayāl Honkyoku Interludes (Music) Entremés (Music) Tonadillas Kacapi-suling -

33559613.Pdf

Raising the Bar: The Reciprocal Roles and Deviant Distinctions of Music and Alcohol in Acadiana by © Marion MacLeod A dissertation submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Ethnomusicology Memorial University of Newfoundland June, 2013 St. John 's, Newfoundland ABSTRACT The role of alcohol in musical settings is regularly relegated to that of incidental by stander, but its pervasive presence as object, symbol or subject matter in Acadian and Cajun performance contexts highlights its constructive capacity in the formation of Acadian and Cajun musical worlds. Individual and collective attitudes towards alcohol consumption implicate a wide number of cultural domains which, in this work, include religious display, linguistic development, respect for social conventions, and the historically-situated construction of identities. This research uses alcohol as an interpretive lens for ethnomusicological understanding and, in so doing, questions the binaries of marginal and mainstream, normal and deviant, sacred and profane, traditional and contemporary, sober and inebriated. Attitudes towards alcohol are informed by, and reflected in, all ofthese cultural conflicts, highlighting how agitated such categorizations can be in lived culture. Throughout the dissertation, I combine the historical examples of HatTy Choates and Cy aMateur with ethnographic examinations of culturally-distinct perfonnative habits, attitudes toward Catholicism, and compositional qualities. Compiling often incongruous combinations of discursive descriptions and enacted displays, my research suggests that opposition actually confirms interdependence. Central to this study is an assertion that levels of cultural competence in Cajun Louisiana and Acadian Nova Scotia are uneven and that the repercussions of this unevenness are musically and behaviourally demonstrated. -

20. Internationales Forum 51

20. internationales forum 51 des jungen films berlin 1990 «SSS y AI ETE AU BAL /1 WENT TO THE DANCE der Cajuns gespielte Musik, der Zydeco, ist eine Verbindung von Cajun-Musik und Blues. The Cajun and Zydeco Music of Louisiana Cajuns, die Nachkommen der 1755 von den Briten aus Akadien Ich ging zum Tanz vertriebenen französischen Siedler, die sich in den fruchtbaren Sumpf gebieten (Bayous) Süd-Louisianas niederließen. Die heute rund 250.000 Cajuns, die eine weitgehend in sich geschlossene Land USA 1989 Volksgruppe bilden, sprechen einen Dialekt aus altertümlichem Produktion Brazos Films, Flower Films Französisch, vermischt mit englischen, spanischen und india (El Cerrito, Kalifornien) nischen Elementen. (Brockhaus' Enzyklopädie des Wissens) Regie Les Blank, Chris Strachwitz nach dem Buch 'Cajun Music: A Reflection of a People* von Ann Allen Savoy Zu diesem Film J'AI ETE AU BAL ist ein abendfüllender Dokumentarfilm über Kamera Les Blank, Susan Kell die Cajun- und Zydeco-Musik aus dem Südwesten Louisianas in Ton Maureen Gosling Vergangenheit und Gegenwart. Chris Strachwitz, Chris Simon Konzertaufhahmen, Photos und historische Filmausschnitte Erzähler/Berater Barry Jean Ancelet werden mit Berichten und Erzählungen zu einem stimmungsvol Michael Doucet len Porträt verwoben. Ann Allen Savoy Schnitt Maureen Gosling Produzenten Les Blank, Chris Strachwitz Les Blank über die Vorgeschichte des Films Assoziierter Produzent Chris Simon Als ich 1970 entdeckte, daß mein erster ganz und gar unabhängig Musik/Mitwirkende produzierter Film The Blues Accordiri