Editor's Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Renewable Energy Sector

Construction, Engineering and Projects The Renewable Energy Sector Hammonds LLP is one of the largest and most respected construction, engineering and projects legal practices with offices throughout the UK, Europe and Asia. For many years we have advised on all aspects of renewable energy projects. Our experience includes biofuels, windfarms, CHP “Hammonds plants, renewables, hydroelectricity, biomass, waste to energy and tidal and wave energy. seems to have ESTABLISHED RENEWABLE ENERGY SECTOR EXPERIENCE discovered the holy grail of top Our team has specialists who are experienced in advising upon drafting and negotiating turbine/ equipment supply agreements, EPC contracts, balance of plant, engineers’ sub-contracts, quality advice electrical and instrumentation sub-contracts, sub-contractors’ collateral warranties, sub- at a reasonable contractors’ novations, grid connection agreements, service agreements, warranty agreements and operation and maintenance agreements on a variety of renewable energy projects both in the cost.” Legal UK and overseas. Week Client We also recognise that sometimes disputes are unavoidable. Whether claimant or respondent, Satisfaction we can advise you on the many different forms of dispute resolution used in the industry. Report, 2009. PROVEN TRACK-RECORD IN THE RENEWABLE ENERGY SECTOR We have experience acting for a range of clients in the Renewable Energy sector including owner-operators, sponsors, licensees, funders, regeneration agencies, developers, contractors (including EPC and EPC–M), professionals, subcontractors and other specialist contractors. Our experience places us in a unique position with a thorough understanding of the risks, liabilities and obligations of all parties in the Renewable Energy sector. Our clients include Manchester Airport, Abengoa, Ineos Fluor, Vattenfall AB, The Cornwall Light and Power Company, Simon Carves, Shaw Group UK Limited, Stone & Webster, Laker-Vent Engineering Ltd, Bristol Myers Squibb, Bomel, Lucite International, Barclays Bank and Royal Bank of Scotland amongst others. -

Product Liability 2016 14Th Edition

ICLG The International Comparative Legal Guide to: Product Liability 2016 14th Edition A practical cross-border insight into product liability work Published by Global Legal Group, in association with CDR, with contributions from: Addleshaw Goddard LLP Herbert Smith Freehills LLP Advokatfirma Ræder DA Lee and Li, Attorneys-at-Law Ali Budiardjo, Nugroho, Reksodiputro Matheson Allen & Gledhill LLP McConnell Valdés LLC Arnold & Porter (UK) LLP MILINERS ABOGADOS Y ASESORES Bahas, Gramatidis & Partners TRIBUTARIOS SLP Bufete Ocampo, Salcedo, Alvarez del Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP Castillo y Ocampo, S. C. Pachiu & Associates Caspi & Co. Pinheiro Neto Advogados Clayton Utz Seth Associates Crown Office Chambers Sidley Austin LLP Drinker Biddle & Reath LLP Squire Patton Boggs Eversheds LLP Synch Advokat AB Gianni, Origoni, Grippo, Cappelli & Partners Taylor Wessing Gowling WLG Tonucci & Partners The International Comparative Legal Guide to: Product Liability 2016 General Chapters: 1 Recent Developments in European Product Liability – Ian Dodds-Smith & Alison Brown, Arnold & Porter (UK) LLP 1 2 Update on U.S. Product Liability Law – Jana D. Wozniak & Daniel A. Spira, Sidley Austin LLP 7 Contributing Editors 3 An Overview of Product Liability and Product Recall Insurance in the UK – Anthony Dempster & Ian Dodds-Smith, Arnold Howard Watson, Herbert Smith Freehills LLP 17 & Porter (UK) LLP and Michael Spencer QC, 4 The Practicalities of Managing a Global Recall – Richard Matthews & Fabian Volz, Eversheds LLP 23 Crown Office Chambers 5 Horizon Scanning – The Future of Product Liability Risks – Louisa Caswell & Mark Chesher, Sales Director Addleshaw Goddard LLP 32 Florjan Osmani Account Directors Country Question and Answer Chapters: Oliver Smith, Rory Smith Sales Support Manager 6 Albania Tonucci & Partners: Artur Asllani, LL.M. -

Global Small-Cap M&A Review

Global Small-Cap M&A Review FIRST HALF 2021 | LEGAL ADVISORS Small-Cap Mergers & Acquisitions Review First Half 2021 | Legal Advisors Global Deals Intelligence Global Scorecard: Announced Small-Cap M&A by Target Nation (Up To US$50mil) SMALL-CAP M&A DEAL MAKING UP 44%; STRONGEST FIRST HALF ON RECORD 01/01/2021 - 06/30/2021 01/01/2020 - 06/30/2020 YoY % YoY % Worldwide small-cap M&A deals valued up to US$50 million (including undisclosed value deals) Target Region / Nation Value ($mil) # of Deals Value ($mil) # of Deals Chg. ($) Chg. (#) Worldwide 116,420.4 25,629 81,121.4 20,237 44% ▲ 27% ▲ reached US$116.4 billion during the first half of 2021, an increase of 44% compared to a year ago Americas 34,430.5 8,356 26,446.7 6,679 30% ▲ 25% ▲ and the strongest opening six-month period for small-cap M&A since records began in 1980. Small- United States of America 26,765.1 6,188 21,031.2 5,083 27% ▲ 22% ▲ cap M&A during the second quarter of 2021 increased 6% compared to the first quarter of this year, Canada 4,766.4 1,479 3,553.0 1,131 34% ▲ 31% ▲ while the number of deals declined by 3% during the second quarter. By number of worldwide Brazil 1,856.1 424 986.1 266 88% ▲ 59% ▲ Mexico 387.6 71 76.0 39 410% ▲ 82% ▲ deals, small-cap deal making increased 27% compared to the first half of 2020, hitting an all-time Chile 161.8 48 145.0 29 12% ▲ 66% ▲ high. -

Lateral Partner Moves in London January

Lateral Partner Moves in London January - February 2021 Welcome to the latest round-up of lateral partner moves in the legal market from Edwards Gibson; where we look back at announced partner-level recruitment activity in London over the past two months and give you a ‘who’s moved where’ update. There were 90 partner hires in the first two months of 2021 which, although 6% down on the 5-year statistical average for the same period, is actually 13% up on last year (80). Indeed, as we have previously discussed, Big Law has, with some exceptions, so far managed to remain remarkably unscathed by the largest economic contraction the UK has ever seen. No fewer than six firms took on three or more partners, with Hogan Lovells nabbing five: a four- partner litigation team (two laterals and two promotion hires) from Debevoise & Plimpton and the co-head of corporate - Patrick Sarch - from White & Case. Top partner recruiters in London January – February 2021 Hogan Lovells 5 Addleshaw Goddard 3 Bracewell 3 Harcus Parker 3 Paul Hastings 3 Squire Patton Boggs 3 Given the inverse relationship between economic activity and commercial disputes, it is unsurprising that nearly a third of all hires were disputes lawyers and 12% were restructuring/ insolvency specialists, with three firms - Armstrong Teasdale, McDermott Will & Emery and Simpson Thacher – launching completely new practices in that space. Firms hiring laterals whose practices were primarily restructuring or insolvency related Armstrong Teasdale (formerly Kerman & Co) Dechert Edwin Coe Faegre Drinker Fried, Frank, Harris, Shriver & Jacobson Goodwin Procter Latham & Watkins McDermott Will & Emery (hired a two-partner team) Simpson Thacher & Bartlett (hired two partners from separate firms) Although demand for restructuring and insolvency specialists clearly remains very high, many lawyers report that work levels remain eerily quiet due to governments across Europe pumping vast amounts of cash into the system to counter a COVID- lockdown induced economic collapse. -

Contributing Editor Andrew Pitts

[ Exclusively for: Squire Patton Boggs | 06-Jul-16, 03:25 PM ] ©Getting The Deal Through GETTING THROUGH THE DEAL Securities Finance Securities Finance Contributing editor Andrew Pitts 2016 2016 © Law Business Research 2016 [ Exclusively for: Squire Patton Boggs | 06-Jul-16, 03:25 PM ] ©Getting The Deal Through Securities Finance 2016 Contributing editor Andrew Pitts Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP Publisher Law The information provided in this publication is Gideon Roberton general and may not apply in a specific situation. [email protected] Business Legal advice should always be sought before taking Research any legal action based on the information provided. Subscriptions This information is not intended to create, nor does Sophie Pallier Published by receipt of it constitute, a lawyer–client relationship. [email protected] Law Business Research Ltd The publishers and authors accept no responsibility 87 Lancaster Road for any acts or omissions contained herein. Business development managers London, W11 1QQ, UK Although the information provided is accurate as of Alan Lee Tel: +44 20 3708 4199 April 2016, be advised that this is a developing area. [email protected] Fax: +44 20 7229 6910 Adam Sargent © Law Business Research Ltd 2016 Printed and distributed by [email protected] No photocopying without a CLA licence. Encompass Print Solutions First published 2004 Tel: 0844 2480 112 Dan White Thirteenth edition [email protected] ISSN 2055-5423 © Law Business -

Law Firms Join Forces to Ensure Firms Are Equipped to Have Conversations About Race

LAW FIRMS JOIN FORCES TO ENSURE FIRMS ARE EQUIPPED TO HAVE CONVERSATIONS ABOUT RACE 25 January 2021 | UK Firm news As organisations across the UK continue efforts to improve ethnic diversity and promote better understanding of race, a number of the UK’s leading law firms have joined forces to provide guidance that will enable effective conversations about race and racism in the workplace. NOTICED, the UK’s first inter-law firm diversity network which is comprised of thirteen City firms, is today launching a new toolkit offering a structured approach to conversations which many individuals otherwise feel is difficult to have. The guide, which can be viewed here addresses a range of issues. It will help individuals identify and deal with micro-aggressions, understand what actions can help them be an effective ally and hold effective conversations in the workplace. The guide also offers a number of practical solutions that law firms can take to improve. These focus on hiring and promotion and how firms can expand support beyond the legal profession. The launch of the guide follows member firms having individually taken a range of actions to address issues relating to race and ethnicity in the workplace*. Law Society of England and Wales president David Greene said: “We are pleased to contribute to NOTICED’s toolkit and hope this provides a useful resource for firms. The events of 2020 and our recent research into the experiences of black, Asian and minority ethnic solicitors has shown that now more than ever it is important for firms and legal businesses to lead from the front and have frank conversations about how to create a more inclusive workforce.” Siddhartha Shukla, senior associate at Herbert Smith Freehills and co-chair of NOTICED, says: "Given the increasing focus on ethnic and cultural diversity following events of 2020, NOTICED was keen to provide something tangible for member firms and the wider legal community to use when trying to improve the quality of conversations about race in the workplace. -

2018 Mergers & Acquisitions

Altman Weil MERGER line TM 2018 KEY STATS # law firms acquired: 106 Average acquired firm size: 27 lawyers % cross-border acquisitions: 13% Average acquirer size: 1,010 lawyers % AmLaw acquirers: 30% Top region targeted: Middle Atlantic 125 102 106 100 91 88 82 85 TOTALS 70 75 60 60 60 Q4 53 50 Q3 39 25 Q2 Q1 0 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2-5 lawyers SIZE 2018 6-20 lawyers 40% 41% 14% 6% acquisitions 21-100 lawyers 0% 100% over 100 lawyers New England REGION Middle Atlantic 2018 South 3% 25% 22% 20% 18% 13% acquisitions Midwest West 0% 100% Cross-border WWW .ALTMANWEIL .COM /MERGERLINE Altman Weil MERGER line TM 2018 ACQUIRED FIRMS: 100+ LAWYERS ACQUIRER ACQUIRED REPORT EFFECTIVE DATE DATE FIRM 1 MAIN OFFICE SIZE FIRM 2 MAIN OFFICE SIZE 2/26/18 4/3/18 Bryan Cave St. Louis 900 & Berwin Leighton Paisner London 666 2/21/18 4/2/18 Hunton & Williams Richmond 683 & Andrews Kurth Houston 311 3/30/18 4/1/18 Foley & Lardner Milwaukee 849 & Gardere Wynne Sewell Dallas 233 4/10/18 4/11/18 Clark Hill Detroit 450 & Strasburger & Price Dallas 195 6/11/18 8/1/18 Nelson Mullins Atlanta 584 & Broad and Cassel Orlando 160 9/20/18 11/1/18 Fox Rothschild Philadelphia 816 & Smith Moore Leatherwood Greensboro 131 ACQUIRED FIRMS: 21 to 100 LAWYERS ACQUIRER ACQUIRED REPORT EFFECTIVE DATE DATE FIRM 1 MAIN OFFICE SIZE FIRM 2 MAIN OFFICE SIZE 8/21/18 11/1/18 Venable Washington 658 & Fitzpatrick Cella Harper & Scinto New York 96 11/1/18 1/1/19 Burr & Forman Birmingham 281 & McNair Columbia SC 84 3/14/18 9/25/18 Dentons New York 8100 -

Law Firm Data Breaches: the Cone of Silence Shatters

Law Firm Data Breaches: The Cone of Silence Shatters By Sharon D. Nelson, Esq. and John W. Simek © 2016 Sensei Enterprises, Inc. For years, the authors (and many others) have been saying that law firms generally keep mum about data breaches. While we have seen a few small firms abide by data breach notification laws, the larger firms generally have not, usually hanging their hat on the “we don’t know what data was compromised” or the “we had an incident, but no evidence of an actual breach or misuse of data” excuses. In fairness, not all data breach notification laws are equal – in some cases, they may not have to disclose Whether they have told their clients is unknown, but speculation has been rising that they often have not, for fear of a mass client exodus. Two Am Law 100 Firm’s Breaches Announced The “Cone of Silence” around law firm data breaches began to shatter on March 29, 2016, when the Wall Street Journal reported that Cravath Swaine and Weil Gotshal, two members of the Am Law 100, were breached in the summer of 2015. Other firms, not named, were reportedly breached as well. The Manhattan U.S. attorney's office and the FBI are probing the breaches. It isn't clear what information may have been compromised. The information in the article came from "people familiar with the matter." Because the story came from the Wall Street Journal, we are quite confident that they verified the information. Cravath acknowledged that there was a "limited breach" but said that the firm is "not aware that any of the information that may have been accessed has been used improperly." The firm said it was working with law enforcement and outside consultants to assess its security. -

Behind the Scenes of Recent Panel Decisions

THE DATA BEHIND THE STORY WHO REPRESENTS WHO Behind the scenes of How they will miss out... previous instructions (2015-16) recent panel decisions Pinsent Masons, DLA Piper, Ashurst and Bird & Bird have all missed out on William Commercial litigationCorporate tax Employment Health and safetyIT and telecomsGaming and bettingPlanning Intellectual propertyAviation Corporate andMergers commercial and acquisitionsBank lending Capital markets Hill’s latest UK adviser panel, with Linklaters and Addleshaw Goddard the only firms to retain their places on the FTSE 250 bookmaker’s slimmed-down roster. Pinsent Masons (August 2017, legalbusiness.co.uk) Ashurst UK supermarket and retailer Sainsbury’s Group has appointed 11 firms to its new legal DLA Piper panel, including Linklaters, Addleshaw Goddard, Dentons and CMS Cameron McKenna Nabarro Olswang. The panel, which was last reviewed in 2014, previously included Bond Bird & Bird Dickinson, DWF and Gowling WLG. (August 2017, legalbusiness.co.uk) HSBC has appointed around ten firms to its UK legal banking panel. Addleshaw Goddard, Eversheds Sutherland and Simmons & Simmons were among those which made the cut. CMS Cameron McKenna, Dentons and Pinsent Masons are also among the roster which was reduced in size. (July 2017, legalbusiness.co.uk) Product liabilityIntellectual propertyBrand managementEnvironment Commercial property:Trade marks retail Debt recovery Corporate tax Planning Spanish banking giant Santander has appointed a host of firms including Slaughter and May, Bond Dickinson Ashurst and Reed -

In the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Eastern District of Virginia Richmond Division

Case 20-32299-KLP Doc 258 Filed 06/09/20 Entered 06/09/20 14:05:46 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 37 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA RICHMOND DIVISION ) In re: ) Chapter 11 ) INTELSAT S.A., et al.1 ) Case No. 20-32299 (KLP) ) Debtors. ) (Jointly Administered) ) AFFIDAVIT OF SERVICE I, Victoria X. Tran, depose and say that I am employed by Stretto, the claims and noticing agent for the Debtors in the above-captioned case. On June 1, 2020, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following documents to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit A: • Debtors’ Motion for Entry of Interim and Final Orders (A) Authorizing the Payment of Certain Prepetition Taxes and Fees and (B) Granting Related Relief (Docket No. 12) • Interim Order (A) Authorizing the Payment of Certain Prepetition Taxes and Fees and (B) Granting Related Relief (Docket No. 135) • Order Setting an Expedited Hearing on “First Day Motions” and for Related Relief (Docket No. 142) Furthermore, on June 1, 2020, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following documents to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit B, and via electronic mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit C: • Notice of Filing Revised Final Order and Documents Related to the Debtors’ Motion for Entry Of a Final Order (A) Authorizing the Debtors To Obtain Postpetition Financing, (B) Granting Liens and Superpriority Administrative Expense Claims, (C) Granting Adequate Protection to the Prepetition Secured Parties, (D) Modifying the Automatic Stay, and (E) Granting Related Relief (Docket No. -

Can't Compete with Hammonds' Franchise Expertise

July 2010 Review Commercial & Dispute Resolution Can’t compete with Hammonds’ franchise expertise Good news for franchisors. In a recent franchisor/franchisee dispute, the High Court has clarified that franchisees can be stopped from competing with the franchisor at the end of the franchise. And Hammonds acted for the successful franchisor in this case. Hammonds acted for the franchisor What did the High Court say? where the High Pirtek (UK) Limited granted Joinplace Limited and Mr Vickers (its director) a franchise to Court confirmed manufacture, sell and service industrial hoses in County Durham for 10 years. The franchise agreement included a restrictive covenant which provided that Mr Vickers would not for one year that franchisees after termination of the agreement and within County Durham: can be stopped “directly or indirectly be engaged or concerned or interested in any capacity whatsoever in any from competing business which carries on a business similar to or which competes with the Pirtek Business”. Just before the franchise agreement was terminated, Mr Vickers set up a new company (named Vetech) which also manufactured, sold and serviced industrial hoses in County Durham. Hammonds successfully obtained an injunction for Pirtek. This prevented Vetech from trading on the basis that this would be a breach of the restrictive covenant. Vetech argued that it was not bound by the restrictive covenant which was in breach of UK and European competition law and so invalid. The High Court found in favour of Pirtek. The restrictive covenant was necessary to protect Pirtek’s goodwill in its business method and to prevent the risk that know-how and assistance provided by Pirtek to Mr Vickers during the franchise agreement would be used to aid Pirtek’s competitors, namely Vetech. -

Q1 M&A League Tables

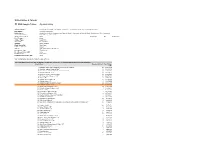

United States & Canada Q1 M&A League Tables (by deal value) Target Industry: Financials, Real Estate, Healthcare, Consumer, Technology, Media and Telecommunications Deal Status: Pending, Completed Entity Types: Acquisition of Whole Company (incl. Majority Stake), Acquisition of Minority Stake, Acquisition of Asset or Branch Target Geography: United States and Canada Announcement Date: From: 01/01/2018 To: 04/01/2018 Deal Features: None Adviser Type: Legal Firm Group By: No Grouping Advised: Buyer or Seller Rank Report By: Deal Value In-House Adviser: Include Criteria: S&P Global Market Intelligence Deal Range Type: Total Assets Deal Range Value ($M): None Ranking Range: Deal Value Ranking Range Value ($M): None S&P Global Market Intelligence M&A coverage universe. Top Legal Advisers in Financials, Real Estate, Healthcare, Consumer, Technology, Media and Telecommunications Rank Firm Number Of Deals Deal Value ($M) 1 Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP & Affiliates* 23 97,847.72 2 Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz* 11 85,738.15 3 Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP* 20 81,972.91 4 Holland & Knight, LLP* 19 55,510.71 5 Simpson Thacher & Bartlett LLP* 16 51,502.03 6 Weil, Gotshal & Manges, LLP* 15 50,878.51 7 Torys LLP* 5 37,762.96 8 Sullivan & Cromwell LLP 11 31,207.85 9 Allen & Overy LLP* 3 19,450.00 10 Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati* 12 19,365.19 11 Goodwin Procter, LLP* 15 17,967.92 12 Davis Polk & Wardwell, LLP* 14 17,911.40 13 Cravath, Swaine & Moore, LLP 3 17,692.37 14 Dechert LLP* 5 17,363.15 15 Norton Rose Fulbright LLP* 3 17,317.50 16 Debevoise & Plimpton LLP* 8 10,586.30 17 Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen and Hamilton 2 10,269.54 18 Proskauer Rose LLP* 5 10,113.70 19 Morrison & Foerster LLP* 10 9,170.33 20 O'Melveny & Myers* 8 8,442.28 21 Law Office of Salman M.