Playing the Najdorf David Vigorito

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Najdorf in Black and White

Grandmaster Bryan Smith The Najdorf In Black and White Boston Contents Introduction: The Cadillac of Openings......................................................................... 5 The Development of the Najdorf Sicilian ...................................................................... 7 Chapter 1: Va Banque: 6.Bg5 .................................................................................. 14 Chapter 2: The Classicist’s Preference: 6.Be2 ......................................................... 36 Chapter 3: Add Some English: 6.Be3 ...................................................................... 52 Chapter 4: In Morphy’s Style: 6.Bc4 ....................................................................... 74 Chapter 5: White to Play and Win: 6.h3 .................................................................. 94 Chapter 6: Systematic: 6.g3 ................................................................................... 110 Chapter 7: Healthy Aggression: 6.f4 ..................................................................... 123 Chapter 8: Action-Reaction: 6.a4 .......................................................................... 136 Chapter 9: Odds and Ends ..................................................................................... 142 Index of Complete Games ......................................................................................... 158 Introduction: The Cadillac of Openings ith this book, I present a collection of games played in the Najdorf Sicilian. WThe purpose of this book -

Play the Semi-Slav

Play the Semi-Slav David Vigorito Quality Chess qualitychessbooks.com First edition 2008 by Quality Chess UK LLP Copyright © 2008 David Vigorito All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. ISBN 978-9185779017 All sales or enquiries should be directed to Quality Chess UK LLP, 20 Balvie Road, Milngavie, Glasgow G62 7TA, United Kingdom e-mail: [email protected] website: www.qualitychessbooks.com Distributed in US and Canada by SCB Distributors, Gardena, California www.scbdistributors.com Edited by John Shaw & Jacob Aagaard Typeset: Colin McNab Cover Design: Vjatseslav Tsekatovski Cover Photo: Ari Ziegler Printed in Estonia by Tallinna Raamatutrükikoja LLC CONTENTS Bibliography 4 Introduction 5 Symbols 10 Part I – The Moscow Variation 1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.¤f3 ¤f6 4.¤c3 e6 5.¥g5 h6 1. Main Lines with 7.e3 13 2. Early Deviations 7.£b3; 7.£c2; 7.g3 29 3. The Anti-Moscow Gambit 6.¥h4 41 Part II – The Botvinnik Variation 1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.¤f3 ¤f6 4.¤c3 e6 5.¥g5 dxc4 4. Main Line 16.¦b1 63 5. Main Line 16.¤a4 79 6. White Plays 9.exf6 95 7. Early Deviations 6.e4 b5 7.a4; 6.a4; 6.e3 105 Part III – The Meran Variation 1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.¤f3 ¤f6 4.¤c3 e6 5.e3 ¤bd7 6.¥d3 dxc4 7.¥xc4 b5 8. -

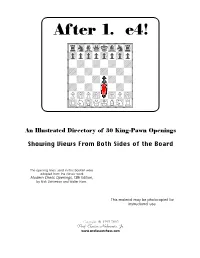

Chess Openings, 13Th Edition, by Nick Defirmian and Walter Korn

After 1. e4! cuuuuuuuuC {rhb1kgn4} {0p0p0p0p} {wdwdwdwd} {dwdwdwdw} {wdwdPdwd} {dwdwdwdw} {P)P)w)P)} {$NGQIBHR} vllllllllV An Illustrated Directory of 30 King-Pawn Openings Showing Views From Both Sides of the Board The opening lines used in this booklet were adopted from the classic work Modern Chess Openings, 13th Edition, by Nick DeFirmian and Walter Korn. This material may be photocopied for instructional use. Copyright © 1998-2002 Prof. Chester Nuhmentz, Jr. www.professorchess.com CCoonntteennttss This booklet shows the first 20 moves of 30 king-pawn openings. Diagrams are shown for every move. These diagrams are from White’s perspective after moves by White and from Black’s perspective after moves by Black. The openings are grouped into 6 sets. These sets are listed beginning at the bottom of this page. Right after these lists are some ideas for ways you might use these openings in your training. A note to chess coaches: Although the openings in this book give approximately even chances to White and Black, it won’t always look that way to inexperienced players. This can present problems for players who are continuing a game after using the opening moves listed in this booklet. Some players will need assistance to see how certain temporarily disadvantaged positions can be equalized. A good example of where some hints from the coach might come in handy is the sample King’s Gambit Declined (Set F, Game 2). At the end of the listed moves, White is down by a queen and has no immediate opportunity for a recapture. If White doesn’t analyze the board closely and misses the essential move Bb5+, he will have a lost position. -

Starting Out: the Sicilian JOHN EMMS

starting out: the sicilian JOHN EMMS EVERYMAN CHESS Everyman Publishers pic www.everymanbooks.com First published 2002 by Everyman Publishers pIc, formerly Cadogan Books pIc, Gloucester Mansions, 140A Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8HD Copyright © 2002 John Emms Reprinted 2002 The right of John Emms to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 857442490 Distributed in North America by The Globe Pequot Press, P.O Box 480, 246 Goose Lane, Guilford, CT 06437·0480. All other sales enquiries should be directed to Everyman Chess, Gloucester Mansions, 140A Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8HD tel: 020 7539 7600 fax: 020 7379 4060 email: [email protected] website: www.everymanbooks.com EVERYMAN CHESS SERIES (formerly Cadogan Chess) Chief Advisor: Garry Kasparov Commissioning editor: Byron Jacobs Typeset and edited by First Rank Publishing, Brighton Production by Book Production Services Printed and bound in Great Britain by The Cromwell Press Ltd., Trowbridge, Wiltshire Everyman Chess Starting Out Opening Guides: 1857442342 Starting Out: The King's Indian Joe Gallagher 1857442296 -

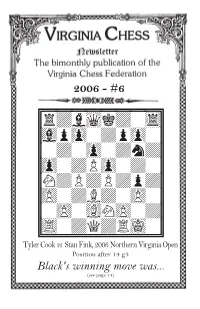

2006-6 Layout.Indd

2006 - #6 ‹óóóóóóóó‹ õÏ›ËÒÙ›‹Ìú õȇ·‹›‡·‹ú õ‹›‹·‹›‰›ú õ·‹›fi·‹›‹ú õ‚›fi›fi›‡›ú õfl‹›Ê›‹fl‹ú õ‹fl‹Á‚fl‹›ú õ΋›Ó›ÍÛ‹ú Tyler‹ìììììììì‹ Cook vs Stan Fink, 2006 Northern Virginia Open Position after 14 g3 Black's winning move was... (see page 14) VIRGINIA CHESS Newsletter 2006 - Issue #6 Editor: Circulation: Macon Shibut Ernie Schlich 8234 Citadel Place 1370 South Braden Crescent Vienna VA 22180 Norfolk VA 23502 [email protected] [email protected] k w r Virginia Chess is published six times per year by the Virginia Chess Federation. Membership benefits (dues: $10/yr adult; $5/yr junior under 18) include a subscription to Virginia Chess. Send material for publication to the editor. Send dues, address changes, etc to Circulation. The Virginia Chess Federation (VCF) is a non- profit organization for the use of its members. Dues for regular adult membership are $10/yr. Junior memberships are $5/ yr. President: Marshall Denny, 4488 Indian River Rd, Virginia Beach VA 23456, [email protected] Treasurer: Ernie Schlich, 1370 South Braden Crescent, Norfolk VA 23502, [email protected] Secretary: Helen Hinshaw, 3430 Musket Dr, Midlothian VA 23113, [email protected] Scholastics Coordinator: Mike Hoffpauir, 405 Hounds Chase, Yorktown VA 23693, [email protected] VCF Inc. Directors: Helen Hinshaw (Chairman), Marshall Denny, Mike Atkins, Mike Hoffpauir, Ernie Schlich. otjnwlkqbhrp 2006 - #6 1 otjnwlkqbhrp Northern Virginia Open by Mike Atkins VER 85 PLAYERS journeyed to Springfield on a crisp fall weekend for in Othe 11th rendition of the Northern Virginia Open, November 4-5. -

![An Introduction to the Sicilian Defense W______W Árhb1kgn4] À0pdp0p0p] ßwdwdwdwd] Þdw0wdwdw] Ýwdsdpdwd] Üdwdwdwdw] ÛP)P)S)P)] Ú$NGQIBHR] Wáâãäåæçèw](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6805/an-introduction-to-the-sicilian-defense-w-w-%C3%A1rhb1kgn4-%C3%A00pdp0p0p-%C3%9Fwdwdwdwd-%C3%BEdw0wdwdw-%C3%BDwdsdpdwd-%C3%BCdwdwdwdw-%C3%BBp-p-s-p-%C3%BA-ngqibhr-w%C3%A1%C3%A2%C3%A3%C3%A4%C3%A5%C3%A6%C3%A7%C3%A8w-2056805.webp)

An Introduction to the Sicilian Defense W______W Árhb1kgn4] À0pdp0p0p] ßwdwdwdwd] Þdw0wdwdw] Ýwdsdpdwd] Üdwdwdwdw] ÛP)P)S)P)] Ú$NGQIBHR] Wáâãäåæçèw

An Introduction to the Sicilian Defense w________w árhb1kgn4] à0pdp0p0p] ßwdwdwdwd] Þdw0wdwdw] ÝwdsdPdwd] Üdwdwdwdw] ÛP)P)s)P)] Ú$NGQIBHR] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw Compiled by Steven Craig Miller Copyright © 2003 Steven Craig Miller Copying and distribution of this article is permitted for noncommercial purposes. An Introduction to the Sicilian Defense complied by Steven Craig Miller Page 2 Table of Contents a. The Scheveningen Variation Introduction 1. e4 c5 2. Nf3 d6 (or e6) Part I: Open Sicilians 3. d4 cxd4 a. The Scheveningen Variation 4. Nxd4 Nf6 b. The Najdorf Variation 5. Nc3 e6 (or d6) c. The Classical Variation w________w d. The Dragon Variation árhb1kgs4] e. The Accelerated Dragon à0pdsdp0p] f. The Sveshnikov Variation ß d 0phwd] g. Löwenthal Variation Þdwdwdwdw] h. The Four Knights Variation Ý dsHPdwd] i. The Kalashnikov Variation ÜdwHwdwdw] j. The Taimanov Variation ÛP)Pds)P)] k. The Kan Variation Ú$sGQIBdR] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw Part II: Other Sicilian Systems l. The c3 Sicilain (Scheveningen is pronounced something m. The Morra Gambit like: Shaw-ven-again). n. The Closed Sicilian o. The Bb5 Systems (1) Classical Scheveningen p. The Grand Prix Attack (2) Modern Scheveningen (3) English Attack Introduction (4) Keres Attack (5) Fischer Attack The Sicilian Defense is the most popular chess opening of all time. Almost a a1. Classical Scheveningen quarter of all games played are Sicilians. While the majority of scholastic games at 6. Be2 a6 the beginning level are symmetrical king 7. 0-0 Be7 pawn openings (1. e4 e5), at higher levels 8. f4 0-0 the most popular answer to 1. e4 is 1. -

Glossary of Chess

Glossary of chess See also: Glossary of chess problems, Index of chess • X articles and Outline of chess • This page explains commonly used terms in chess in al- • Z phabetical order. Some of these have their own pages, • References like fork and pin. For a list of unorthodox chess pieces, see Fairy chess piece; for a list of terms specific to chess problems, see Glossary of chess problems; for a list of chess-related games, see Chess variants. 1 A Contents : absolute pin A pin against the king is called absolute since the pinned piece cannot legally move (as mov- ing it would expose the king to check). Cf. relative • A pin. • B active 1. Describes a piece that controls a number of • C squares, or a piece that has a number of squares available for its next move. • D 2. An “active defense” is a defense employing threat(s) • E or counterattack(s). Antonym: passive. • F • G • H • I • J • K • L • M • N • O • P Envelope used for the adjournment of a match game Efim Geller • Q vs. Bent Larsen, Copenhagen 1966 • R adjournment Suspension of a chess game with the in- • S tention to finish it later. It was once very common in high-level competition, often occurring soon af- • T ter the first time control, but the practice has been • U abandoned due to the advent of computer analysis. See sealed move. • V adjudication Decision by a strong chess player (the ad- • W judicator) on the outcome of an unfinished game. 1 2 2 B This practice is now uncommon in over-the-board are often pawn moves; since pawns cannot move events, but does happen in online chess when one backwards to return to squares they have left, their player refuses to continue after an adjournment. -

Yermolinsky Alex the Road To

Contents Symbols 4 Introduction 5 A Sneak Preview into what this book is really about 7 Indecisiveness is Evil 7 Ruled by Emotions 12 Part 1: Trends, Turning Points and Emotional Shifts 18 A Really Long Game with a Little Bonus 20 Tr end-Breaking To ols 30 Burn Bridges Now or Preserve the Status Quo? 46 The Burden of Small Advantages 51 Surviving the Monster 58 Part 2: Openings and Early Middlegame Structures 65 The Exchange QGD: Staying Flexible in a Rigid Pawn Structure 67 What Good are Central Pawns against the Griinfeld Defence? 74 Side-stepping the 'Real' Benko 90 Relax; It's Just a Benoni 105 The Once-Feared Grand Prix Attack Now Rings Hollow 113 On the War Path: The Sicilian Counterattack 126 The Pros and Cons of the Double Fianchetto 142 A Final Word on Openings 154 Part 3: Tactical Mastery and Strategic Skills 161 What Exchanges are For 163 Classics Revisited or the Miseducation of Alex Yermolinsky 171 Back to the Exchanging Business- The New Liberated Approach 176 From Calculable Tactics to Combinational Understanding 183 Number of Pawns is just another Positional Factor 199 Let's Talk Computer Chess 216 Index of Openings 223 Index of Players 223 + check ++ double check # checkmate ! ! brilliant move good move !? interesting move ?! dubious move ? bad move ?? blunder +- White is winning ± White is much better ;!; White is slightly better equal position + Black is slightly better + Black is much better -+ Black is winning Ch championship G/60 time limit of 60 minutes for the whole game 1-0 the game ends in a win for White If2-lh the game ends in a draw 0-1 the game ends in a win for Black (D) see next diagram The book you are about to read is essentially a yourself as a chess-player. -

Chess Chatter

Chess Chatter Newsletter of the Port Huron Chess Club Editor: Lon Rutkofske November 2010 Vol.29. Number 11 The Port Huron Chess Club meets Thursdays, except holidays, from 6:30-10:00 PM, at Palmer Park Recreation Center, 2829 Armour Street, (NE corner of Garfield Street and Gratiot Ave…1 mile North of the Blue Water Bridge) Port Huron, Michigan. Everyone is welcome. All equipment provided. Website: http://porthuronchessclub.yolasite.com/ Efim and Me – by Bill Wingrove I began studying chess in 1975. My wife Jane and I had moved from Western New York to Royal Oak where she had a job. I would be unemployed for a year and studying chess helped pass the time. Those were pre-internet and pre-computer times, and getting chess material was difficult. The famous Spassky-Fischer match had been three years earlier, and a lot of the available stuff was from Fischer’s games. I pretty much copied Fischer’s opening repertoire. This is not because I was a fan; Fischer was a pretty reprehensible character away from the chessboard. Fischer’s games were the most available. To this day I play the Sicilian Najdorf, the Grunfeld and the Ruy Lopez. Fischer played the King’s Indian a lot, but I did not think I needed two queen pawn defenses. My opening repertoire has always been quite narrow. Recently, I have started looking at other openings, and it is helpful to see similar patterns arising out of different openings. A name that came up in Fischer’s games was Efim Geller. Most associate Boris Spassky with Fischer. -

Magnus Carlsen

Magnus Carlsen From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search This article is about the Norwegian chess player. For people with a similar name, see Magnus Carlsson (disambiguation). Magnus Carlsen Magnus Carlsen, 2008 Full name Sven Magnus Øen Carlsen Country Norway 30 November 1990 (age 19) Born Tønsberg, Norway Title Grandmaster 2826 FIDE rating (No. 1 in the September 2010 FIDE World Rankings) Peak rating 2826 (July 2010) Sven Magnus Øen Carlsen (born 30 November 1990) is a Norwegian chess Grandmaster and chess prodigy currently ranked number one in the world on the official FIDE rating list. He has achieved the second highest ever rating exceeded only by Garry Kasparov.[1][2] On 26 April 2004 Carlsen became a Grandmaster at the age of 13 years, 148 days, making him the third-youngest Grandmaster in history. On 1 January 2010 the new FIDE rating list was published, and at the age of 19 years, 32 days he became the youngest chess player in history to be ranked world number one, breaking the record previously held by Vladimir Kramnik.[3] Carlsen is also the 2009 World blitz chess champion. His performance at the September–October 2009 Nanjing Pearl Spring tournament has been described as one of the greatest in history[4] and lifted him to an Elo rating of 2801, making him the fifth player to achieve a rating over 2800 – and aged 18 years 10 months at the time, by far the youngest to do so. Based on his rating, Carlsen has qualified for the Candidates Tournament which will determine the challenger to face World Champion Viswanathan Anand in the World Chess Championship 2012. -

101 Tactical Tips

0 | P a g e 101 Tactical Tips By Tim Brennan http://tacticstime.com Version 1.00 March, 2012 This material contains elements protected under International and Federal Copyright laws and treaties. Any unauthorized reprint or use of this material is prohibited 101 Tactical Tips Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 101 Tactical Tips Openings and Tactics ............................................................................................................. 2 Books and Tactics .................................................................................................................. 4 Computers and Tactics .......................................................................................................... 6 Quotes about Tactics ............................................................................................................. 9 Tactics Improvement ............................................................................................................ 12 Tactics and Psychology ........................................................................................................ 14 Tactics Problems .................................................................................................................. 16 Tactical Motifs ..................................................................................................................... 17 Tactics -

The Sicilian Najdorf 6 Bg5 KEVIN GOH WEI MING

CHESS DEVELOPMENTS The Sicilian Najdorf 6 Bg5 KEVIN GOH WEI MING www.everymanchess.com About the Author Kevin Goh Wei Ming is an International Master and a six-time National Champion of Sin- gapore in classical chess. He has represented Singapore in five Olympiads and other major team tournaments such as the Asian Nations Cup, Asian Indoor Games and South-East Asian Games. Kevin has gained two grandmaster norms. Outside of playing, he was a col- umnist on the chess theory website chesspublishing.com. Chess Developments: Sicilian Na- jdorf 6 Íg5 is his first book project. Contents About the Author 3 Bibliography 5 Foreword by GM Thomas Luther 7 Introduction 9 1 The Trendy 6...Ìbd7 14 2 The Good Old Polugaevsky, the MVLV and 7...Ëc7 107 3 The Classical Variation 184 4 Poisoned Pawn Variation with 10 f5 267 5 Poisoned Pawn Variation with 10 e5 310 6 The Delayed Poisoned Pawn Variation 337 Index of Variations 387 Index of Complete Games 393 Foreword by GM Thomas Luther, 3-time German Champion The Najdorf is known as the opening of the world champions. White has numerous replies, but the most challenging move is 6 Íg5. Some of the most remarkable games in all of chess history have featured this variation. Indeed, the 6 Íg5 line could just be studied out of pure joy for the historical games and all the entertaining tactical ideas which can easily occur. One might argue that 6 Íg5 is nowadays more popular than ever. I recommend to all my students to play this line.