The New Winawer Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faszination Schach

Faszination Schach Ob in Afrika, Australien, Asien, Europa, Süd- oder Nordamerika, in Parks, am Straßenrand, in edlen oder weni - ger edlen Turniersälen, in Schwimmbädern, im Internet oder gegen Gegner aus Fleisch und Blut, um Geld oder ohne Einsatz, mit einer Minute Bedenkzeit oder ohne Zeitlimit – rund um die Uhr spielen Millionen von Menschen in aller Welt Schach. Lebendschach Garry Kasparow (© H. Schaack) rsonnen wurde die Vorform des heutigen Schachs etwa 500 nach Christus in Indien, von dort kam es durch Krieg und Handel nach Persien, später dann in den arabischen Raum und mit den Eroberungszügen der Araber schließlich nach Europa. Ende des 15. Jahrhunderts, als sich die europäische Weltsicht durch die Entdeckung Amerikas erweiterte und Isabella von Kastilien die mächtigste Frau der Welt war, wurden Läufer und Dame stärker und das heutige Schach entstand. Schon immer war Schach mit Kultur und Geschichte der jeweiligen Epoche verknüpft. Wissen Sie, Genosse Großmeister, ich bin nicht gerne Minister, ich würde lieber Schach spielen wie Sie oder eine Revolution in Venezuela machen. Antike Schachuhr Che Guerava , 1928-1967, Revolutionär und Foto-Ikone 2 Kasparow beim Simultan Schaupartie Könige, Kalifen und Fürsten förderten das Spiel, muslimische und Schach hat eine lange Geschichte mit vielen Facetten. Einige davon christliche Eiferer verboten es, im Mittelalter gehörte Schach zu den will diese Broschüre zeigen, denn 1.500 Jahre nach seiner Entstehung Künsten, die ein Ritter beherrschen musste, die Denker der Aufklä- fasziniert Schach immer noch – und macht jede Menge Spaß. rung trafen sich im Schachcafé und in der Sowjetunion war Schach Staatsangelegenheit. Früher kamen die besten Spieler der Welt aus Europa und den USA, heute ist das Spitzenschach globaler. -

Annex 67 (Page 1/1)

Annex 67 (Page 1/1) 75th FIDE CONGRESS CALVIA, MALLORCA, SPAIN 21-31 October 2004 Sol Antillas Hotel Committee/Commission: Chess Exhibition, Art and Philately Chairman: L. Schmid Date: 23 October 2004 Venue: Sala Cabrera Present: Mr. David Jarrett (ENG), Mr. Ady Christophel (LUX), Mr. Gregorio Hernandez Santana (ESP), Mr. Robert Tanner (USA), Mr. Thanit Thamsukati (THA), Mr. Jerry Walsh (ENG), Mr. Nizar Elhaj (LBA), Cynthia Gyrney (ENG), Robert Gurney (ENG), Philip Viner (AUS). The participants of the meeting got the agenda and also the annual report of the FIDE Chess and Art Commission “Summary of the Chess Cultural Activities during the year 2003 and 2004” (both enclosed). The Chairman of the Commission closely worked together with CCI (Chess Collectors International), mainly with Dr. Thomas Thomsen and with the Emanuel Lasker Society in Berlin. We plan to establish a museum in Berlin for all items regarding the former World Champion Emanuel Lasker, perhaps together with the Michael Tal archive. A collection of very fine chessmen and a good part of the chess library from Lothar Schmid might be added. Furtheron we discussed matters connected with “Culture 2000” partners search for the annual project that is called Let´s Play Chess! The Culture of Game in Europe (Italy). The partner would be Dr. Elisabetta Lazzaro from the Brussels office. About Chess Philately and new cancellations Messrs. Jarrett and Christophel told about recent developments. The last point of the discussion was the fate of the former World Champion Bobby Fischer who went to jail in Japan. There were letters written from Boris Spassky and FIDE President Ilyumzhinov to the American President Bush, but up to now without success. -

The Najdorf in Black and White

Grandmaster Bryan Smith The Najdorf In Black and White Boston Contents Introduction: The Cadillac of Openings......................................................................... 5 The Development of the Najdorf Sicilian ...................................................................... 7 Chapter 1: Va Banque: 6.Bg5 .................................................................................. 14 Chapter 2: The Classicist’s Preference: 6.Be2 ......................................................... 36 Chapter 3: Add Some English: 6.Be3 ...................................................................... 52 Chapter 4: In Morphy’s Style: 6.Bc4 ....................................................................... 74 Chapter 5: White to Play and Win: 6.h3 .................................................................. 94 Chapter 6: Systematic: 6.g3 ................................................................................... 110 Chapter 7: Healthy Aggression: 6.f4 ..................................................................... 123 Chapter 8: Action-Reaction: 6.a4 .......................................................................... 136 Chapter 9: Odds and Ends ..................................................................................... 142 Index of Complete Games ......................................................................................... 158 Introduction: The Cadillac of Openings ith this book, I present a collection of games played in the Najdorf Sicilian. WThe purpose of this book -

SHOWCASE BC 831 Funding Offers for BC Artists

SHOWCASE BC 831 Funding Offers for BC Artists Funding offers were sent to the following artists on April 17 + April 21, 2020. Artists have until May 15, 2020, to accept the grant. A Million Dollars in Pennies ArkenFire Booty EP Abraham Arkora BOSLEN ACTORS Art d’Ecco Bratboy Adam Bailie Art Napoleon Bre McDaniel Adam Charles Wilson Asha Diaz Brent Joseph Adam Rosenthal Asheida Brevner Adam Winn Ashleigh Adele Ball Bridal Party Adera A-SLAM Bring The Noise Adewolf Astrocolor Britt A.M. Adrian Chalifour Autogramm Brooke Maxwell A-DUB AutoHeart Bruce Coughlan Aggression Aza Nabuko Buckman Coe Aidan Knight Babe Corner Bukola Balogan Air Stranger Balkan Shmalkan Bunnie Alex Cuba bbno$ Bushido World Music Alex Little and The Suspicious Beamer Wigley C.R. Avery Minds Bear Mountain Cabins In The Clouds Alex Maher Bedouin Soundclash Caitlin Goulet Alexander Boynton Jr. Ben Cottrill Cam Blake Alexandria Maillot Ben Dunnill Cam Penner Alien Boys Ben Klick Camaro 67 Alisa Balogh Ben Rogers Capri Everitt Alpas Collective Beth Marie Anderson Caracas the Band Alpha Yaya Diallo Betty and The Kid Cari Burdett Amber Mae Biawanna Carlos Joe Costa Andrea Superstein Big John Bates Noirchestra Carmanah Andrew Judah Big Little Lions Carsen Gray Andrew Phelan Black Mountain Whiskey Carson Hoy Angela Harris Rebellion Caryn Fader Angie Faith Black Wizard Cassandra Maze Anklegod Blackberry Wood Cassidy Waring Annette Ducharme Blessed Cayla Brooke Antoinette Blonde Diamond Chamelion Antonio Larosa Blue J Ché Aimee Dorval Anu Davaasuren Blue Moon Marquee Checkmate -

Play the Semi-Slav

Play the Semi-Slav David Vigorito Quality Chess qualitychessbooks.com First edition 2008 by Quality Chess UK LLP Copyright © 2008 David Vigorito All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. ISBN 978-9185779017 All sales or enquiries should be directed to Quality Chess UK LLP, 20 Balvie Road, Milngavie, Glasgow G62 7TA, United Kingdom e-mail: [email protected] website: www.qualitychessbooks.com Distributed in US and Canada by SCB Distributors, Gardena, California www.scbdistributors.com Edited by John Shaw & Jacob Aagaard Typeset: Colin McNab Cover Design: Vjatseslav Tsekatovski Cover Photo: Ari Ziegler Printed in Estonia by Tallinna Raamatutrükikoja LLC CONTENTS Bibliography 4 Introduction 5 Symbols 10 Part I – The Moscow Variation 1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.¤f3 ¤f6 4.¤c3 e6 5.¥g5 h6 1. Main Lines with 7.e3 13 2. Early Deviations 7.£b3; 7.£c2; 7.g3 29 3. The Anti-Moscow Gambit 6.¥h4 41 Part II – The Botvinnik Variation 1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.¤f3 ¤f6 4.¤c3 e6 5.¥g5 dxc4 4. Main Line 16.¦b1 63 5. Main Line 16.¤a4 79 6. White Plays 9.exf6 95 7. Early Deviations 6.e4 b5 7.a4; 6.a4; 6.e3 105 Part III – The Meran Variation 1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.¤f3 ¤f6 4.¤c3 e6 5.e3 ¤bd7 6.¥d3 dxc4 7.¥xc4 b5 8. -

Reshevsky Wins Playoff, Qualifies for Interzonal Title Match Benko First in Atlantic Open

RESHEVSKY WINS PLAYOFF, TITLE MATCH As this issue of CHESS LIFE goes to QUALIFIES FOR INTERZONAL press, world champion Mikhail Botvinnik and challenger Tigran Petrosian are pre Grandmaster Samuel Reshevsky won the three-way playoff against Larry paring for the start of their match for Evans and William Addison to finish in third place in the United States the chess championship of the world. The contest is scheduled to begin in Moscow Championship and to become the third American to qualify for the next on March 21. Interzonal tournament. Reshevsky beat each of his opponents once, all other Botvinnik, now 51, is seventeen years games in the series being drawn. IIis score was thus 3-1, Evans and Addison older than his latest challenger. He won the title for the first time in 1948 and finishing with 1 %-2lh. has played championship matches against David Bronstein, Vassily Smyslov (three) The games wcre played at the I·lerman Steiner Chess Club in Los Angeles and Mikhail Tal (two). He lost the tiUe to Smyslov and Tal but in each case re and prizes were donated by the Piatigorsky Chess Foundation. gained it in a return match. Petrosian became the official chal By winning the playoff, Heshevsky joins Bobby Fischer and Arthur Bisguier lenger by winning the Candidates' Tour as the third U.S. player to qualify for the next step in the World Championship nament in 1962, ahead of Paul Keres, Ewfim Geller, Bobby Fischer and other cycle ; the InterzonaL The exact date and place for this event havc not yet leading contenders. -

Chess Openings, 13Th Edition, by Nick Defirmian and Walter Korn

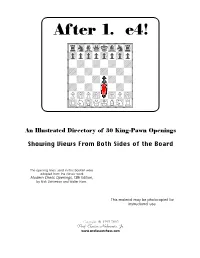

After 1. e4! cuuuuuuuuC {rhb1kgn4} {0p0p0p0p} {wdwdwdwd} {dwdwdwdw} {wdwdPdwd} {dwdwdwdw} {P)P)w)P)} {$NGQIBHR} vllllllllV An Illustrated Directory of 30 King-Pawn Openings Showing Views From Both Sides of the Board The opening lines used in this booklet were adopted from the classic work Modern Chess Openings, 13th Edition, by Nick DeFirmian and Walter Korn. This material may be photocopied for instructional use. Copyright © 1998-2002 Prof. Chester Nuhmentz, Jr. www.professorchess.com CCoonntteennttss This booklet shows the first 20 moves of 30 king-pawn openings. Diagrams are shown for every move. These diagrams are from White’s perspective after moves by White and from Black’s perspective after moves by Black. The openings are grouped into 6 sets. These sets are listed beginning at the bottom of this page. Right after these lists are some ideas for ways you might use these openings in your training. A note to chess coaches: Although the openings in this book give approximately even chances to White and Black, it won’t always look that way to inexperienced players. This can present problems for players who are continuing a game after using the opening moves listed in this booklet. Some players will need assistance to see how certain temporarily disadvantaged positions can be equalized. A good example of where some hints from the coach might come in handy is the sample King’s Gambit Declined (Set F, Game 2). At the end of the listed moves, White is down by a queen and has no immediate opportunity for a recapture. If White doesn’t analyze the board closely and misses the essential move Bb5+, he will have a lost position. -

Starting Out: the Sicilian JOHN EMMS

starting out: the sicilian JOHN EMMS EVERYMAN CHESS Everyman Publishers pic www.everymanbooks.com First published 2002 by Everyman Publishers pIc, formerly Cadogan Books pIc, Gloucester Mansions, 140A Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8HD Copyright © 2002 John Emms Reprinted 2002 The right of John Emms to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 857442490 Distributed in North America by The Globe Pequot Press, P.O Box 480, 246 Goose Lane, Guilford, CT 06437·0480. All other sales enquiries should be directed to Everyman Chess, Gloucester Mansions, 140A Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8HD tel: 020 7539 7600 fax: 020 7379 4060 email: [email protected] website: www.everymanbooks.com EVERYMAN CHESS SERIES (formerly Cadogan Chess) Chief Advisor: Garry Kasparov Commissioning editor: Byron Jacobs Typeset and edited by First Rank Publishing, Brighton Production by Book Production Services Printed and bound in Great Britain by The Cromwell Press Ltd., Trowbridge, Wiltshire Everyman Chess Starting Out Opening Guides: 1857442342 Starting Out: The King's Indian Joe Gallagher 1857442296 -

Ohio Chess Bulletin

Ohio Chess Bulletin Volume 68 September 2015 Number 4 OCA Officers The Ohio Chess Bulletin published by the President: Evan Shelton 8241 Turret Dr., Ohio Chess Association Blacklick OH 43004 (614)-425-6514 Visit the OCA Web Site at http://www.ohiochess.org [email protected] Ohio Chess Association Trustees Vice President: Michael D. Joelson 12200 Fairhill Rd - E293 District Trustee Contact Information Cleveland, OH 44120 1 Cuneyd 5653 Olde Post Rd [email protected] Tolek Syvania OH 43560 (419) 376-7891 Secretary: Grant Neilley [email protected] 2720 Airport Drive Columbus, OH 43219-2219 2 Michael D. 12200 Fairhill Rd - E293 (614)-418-1775 Joelson Cleveland, OH 44120 [email protected] [email protected] Treasurer/Membership Chair: 3 John 2664 Pine Shore Drive Cheryl Stagg Dowling Lima OH 45806 7578 Chancery Dr. [email protected] Dublin, OH 43016 (614) 282-2151 4 Eric 1799 Franklin Ave [email protected] Gittrich Columbus OH. 43205 (614)-843-4300 OCB Editor: Michael L. Steve [email protected] 3380 Brandonbury Way Columbus, OH 43232-6170 5 Joseph E. 7125 Laurelview Circle NE (614) 833-0611 Yun Canton, OH 44721-2851 [email protected] (330) 492-8332 [email protected] Inside this issue... 6 Riley D. 18 W. Fifth Street – Mezzanine Driver Dayton OH 45402 Points of Contact 2 (937) 461-6283 Message from the President 3 [email protected] Editor Note/Correction 4 2014/2015 Ohio Grand Prix 7 Steve 1383 Fairway Dr. Final Standings 4 Charles Grove City OH 43123 MOTCF Addendum 5 (614) 309-9028 -

Chess Pieces – Left to Right: King, Rook, Queen, Pawn, Knight and Bishop

CCHHEESSSS by Wikibooks contributors From Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled "GNU Free Documentation License". Image licenses are listed in the section entitled "Image Credits." Principal authors: WarrenWilkinson (C) · Dysprosia (C) · Darvian (C) · Tm chk (C) · Bill Alexander (C) Cover: Chess pieces – left to right: king, rook, queen, pawn, knight and bishop. Photo taken by Alan Light. The current version of this Wikibook may be found at: http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Chess Contents Chapter 01: Playing the Game..............................................................................................................4 Chapter 02: Notating the Game..........................................................................................................14 Chapter 03: Tactics.............................................................................................................................19 Chapter 04: Strategy........................................................................................................................... 26 Chapter 05: Basic Openings............................................................................................................... 36 Chapter 06: -

Winawer First Edition 2019 by Thinkers Publishing Copyright © 2019 David Miedema

The Modernized French Defense Volume 1: Winawer First edition 2019 by Thinkers Publishing Copyright © 2019 David Miedema All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. All sales or enquiries should be directed to Thinkers Publishing, 9850 Landegem, Belgium. Email: [email protected] Website: www.thinkerspublishing.com Managing Editor: Romain Edouard Assistant Editor: Daniël Vanheirzeele Proofreading: Bernard Carpinter Software: Hub van de Laar Cover Design: Iwan Kerkhof Graphic Artist: Philippe Tonnard Back cover photo: Evert van de Worp and Aventus Production: BESTinGraphics ISBN: 9789492510495 D/2019/13730/2 The Modernized French Defense Volume 1: Winawer David Miedema Thinkers Publishing 2019 Key to Symbols ! a good move ⩲ White stands slightly better ? a weak move ⩱ Black stands slightly better !! an excellent move ± White has a serious advantage ?? a blunder ∓ Black has a serious advantage !? an interesting move +- White has a decisive advantage ?! a dubious move -+ Black has a decisive advantage □ only move → with an attack N novelty ↑ with an initiative ⟳ lead in development ⇆ with counterplay ⨀ zugzwang ∆ with the idea of = equality ⌓ better is ∞ unclear position ≤ worse is © with compensation for the + check sacrificed material # mate Bibliography John Watson, Play the French Viktor Moskalenko, The Wonderful -

Move Similarity Analysis in Chess Programs

Move similarity analysis in chess programs D. Dailey, A. Hair, M. Watkins Abstract In June 2011, the International Computer Games Association (ICGA) disqual- ified Vasik Rajlich and his Rybka chess program for plagiarism and breaking their rules on originality in their events from 2006-10. One primary basis for this came from a painstaking code comparison, using the source code of Fruit and the object code of Rybka, which found the selection of evaluation features in the programs to be almost the same, much more than expected by chance. In his brief defense, Rajlich indicated his opinion that move similarity testing was a superior method of detecting misappropriated entries. Later commentary by both Rajlich and his defenders reiterated the same, and indeed the ICGA Rules themselves specify move similarity as an example reason for why the tournament director would have warrant to request a source code examination. We report on data obtained from move-similarity testing. The principal dataset here consists of over 8000 positions and nearly 100 independent engines. We comment on such issues as: the robustness of the methods (upon modifying the experimental conditions), whether strong engines tend to play more similarly than weak ones, and the observed Fruit/Rybka move-similarity data. 1. History and background on derivative programs in computer chess Computer chess has seen a number of derivative programs over the years. One of the first was the incident in the 1989 World Microcomputer Chess Cham- pionship (WMCCC), in which Quickstep was disqualified due to the program being \a copy of the program Mephisto Almeria" in all important areas.