Learning Through Networks the Story of a Remarkable Collaborative Process and Its Implications for the Future of Organizational and Community Capacity Building

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

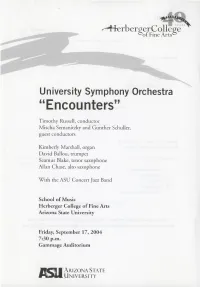

University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters"

FierbergerCollegeYEARS of Fine Arts University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters" Timothy Russell, conductor Mischa Semanitzky and Gunther Schuller, guest conductors Kimberly Marshall, organ David Ballou, trumpet Seamus Blake, tenor saxophone Allan Chase, alto saxophone With the ASU Concert Jazz Band School of Music Herberger College of Fine Arts Arizona State University Friday, September 17, 2004 7:30 p.m. Gammage Auditorium ARIZONA STATE M UNIVERSITY Program Overture to Nabucco Giuseppe Verdi (1813 — 1901) Timothy Russell, conductor Symphony No. 3 (Symphony — Poem) Aram ifyich Khachaturian (1903 — 1978) Allegro moderato, maestoso Allegro Andante sostenuto Maestoso — Tempo I (played without pause) Kimberly Marshall, organ Mischa Semanitzky, conductor Intermission Remarks by Dean J. Robert Wills Remarks by Gunther Schuller Encounters (2003) Gunther Schuller (b.1925) I. Tempo moderato II. Quasi Presto III. Adagio IV. Misterioso (played without pause) Gunther Schuller, conductor *Out of respect for the performers and those audience members around you, please turn all beepers, cell phones and watches to their silent mode. Thank you. Program Notes Symphony No. 3 – Aram Il'yich Khachaturian In November 1953, Aram Khachaturian acted on the encouraging signs of a cultural thaw following the death of Stalin six months earlier and wrote an article for the magazine Sovetskaya Muzika pleading for greater creative freedom. The way forward, he wrote, would have to be without the bureaucratic interference that had marred the creative efforts of previous years. How often in the past, he continues, 'have we listened to "monumental" works...that amounted to nothing but empty prattle by the composer, bolstered up by a contemporary theme announced in descriptive titles.' He was surely thinking of those countless odes to Stalin, Lenin and the Revolution, many of them subdivided into vividly worded sections; and in that respect Khachaturian had been no less guilty than most of his contemporaries. -

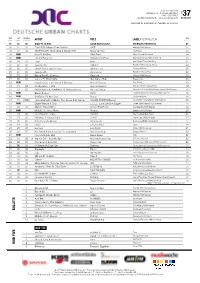

Bullets High Five

DUC REDAKTION Hofweg 61a · D-22085 Hamburg T 040 - 369 059 0 WEEK 37 [email protected] · www.trendcharts.de 03.09.2020 Approved for publication on Tuesday, 08.09.2020 THIS LAST WEEKS IN PEAK WEEK WEEK CHARTS ARTIST TITLE LABEL/DISTRIBUTOR POSITION 01 03 02 Drake Ft. Lil Durk Laugh Now Cry Later OVO/Republic/UMI/Universal 01 02 01 03 Cardi B Ft. Megan Thee Stallion WAP Atlantic/WMI/Warner 01 03 02 04 A$AP Ferg Ft. Nicki Minaj & MadeinTYO Move Ya Hips RCA/Sony 02 04 NEW Nas Ft. Hit-Boy Ultra Black Mass Appeal/Universal 04 05 NEW Capital Bra x Cro Frühstück In Paris Bra Musik/Urban/VEC/Universal 05 06 04 07 Tyga Ibiza Last Kings/Columbia/Sony 01 07 08 08 Apache 207 Bläulich TwoSides/Four Music/Sony 03 08 06 03 Jawsh 685 x Jason Derulo Savage Love Columbia/Sony 06 09 07 05 Apache 207 Unterwegs TwoSides/Four/Sony 03 10 16 02 Burna Boy Ft. Stormzy Real Life Atlantic/WMI/Warner 10 11 05 04 Juicy J Ft. Wiz Khalifa Gah Damn High Trippy/eOne 05 12 NEW Headie One Ft. AJ Tracey & Stormzy Ain't It Different Epic/Sony 12 13 18 09 Kynda Gray Ft. RIN Ayo Technology Division/Gold League/Sony 12 14 13 02 David Guetta & HUMAN(X) Ft. Various Artists Pa' La Cultura What A DJ/HUMAN(X)/Warner Latina/WMI/Warner 13 15 NEW Bausa & Juju 2012____ Downbeat/Warner Germany/WMD/Warner 15 16 NEW 24kGoldn Ft. Iann Dior Mood Columbia/Sony 16 17 10 10 Jack Harlow Ft. -

YOU CAN BE FUNNY Comedy Group Welcomes Newcomers

INSIDE Siouxland singer signs record deal weekender YOU CAN BE FUNNY Comedy group welcomes newcomers MANY EVENTS THIS WEEK SIOUX CITY’S FREE READ | JULY 23-29, 2020 | VOL. 21 ISSUE 34 | AT WWW.SIOUXLAND.NET: EVENTS,www.siouxland.netwww.siouxland.net MOVIE LISTINGS, . 07.23.2020 |BANDS 06.07.12 & | . MOREWeekenderWeekender |. 1 Submit an event: Do you have QUESTION OF THE WEEK an event you’d like to submit to our calendar? Call 712-293-4313, e-mail [email protected] or enter online at www.siouxland.net. Include event date, time, event name, contact name and phone If you had a soundtrack for your life, number. Deadline: Noon the Friday prior to what would be your theme song? publication. (Early deadlines in effect the week before holidays). CALENDAR BARS / PUBS JULY 23 Board Game Night, Brightside JULY 24 Cafe, 525 Fourth St., Sioux Chad Pauling Earl Horlyk Patrick Rooney Nikki Ahlquist Trailer Park Boys Trivia, The City. For a $5 cover charge you Retail and Digital Staff Writer Account Executive Graphic Designer Marquee, 1225 Fourth St., can access our ever-growing Advertising Director [email protected] prooney@ [email protected] Sioux City. Trivia Night at the board game library. Pizza and cpauling Since I had major dental siouxcityjournal.com My theme song would Marquee. (712) 560-4288. 8-10 grilled paninis are served along @siouxcityjournal.com surgery performed last It would be my favorite either be “Too Much p.m. with snack foods like chips and Given the world now: Brett week, “I Wanna Be song, “It’s a Beautiful Blood” or “Handwritten” muffins. -

Footnoted and Annotated Script

Footnoted and Annotated Script By Annie Leonard One of the problems with trying to use less stuff is that sometimes we feel like we really need it. What if you live in a city like, say, Cleveland and you want a glass of water? Are you going to take your chances and get it from the city tap? Or should you reach for a bottle of water that comes from the pristine rainforests of… Fiji? Well, Fiji brand water thought the answer to this question was obvious. So they built a whole ad campaign around it. It turned out to be one of the dumbest moves in advertising history.1 See the city of Cleveland didn’t like being the butt of Fiji’s joke so they did some tests and guess what? These tests showed a glass of Fiji water is lower quality, it loses taste tests against Cleveland tap and costs thousands of times more. 2 This story is typical of what happens when you test bottled water against tap water. Is it cleaner? Sometimes, sometimes not: in many ways, bottled water is less regulated than tap.3 Is it tastier? In taste tests across the country, people consistently choose tap over bottled water.4 These bottled water companies say they’re just meeting consumer demand - But who would demand a less sustainable, less tasty, way more expensive product, especially one you can get almost free in your 1. Fiji’s ad ran in national magazines with the tagline, “The label says 3. Municipal water in the U.S. -

Most Requested Songs of 2020

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2020 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 4 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 7 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 8 V.I.C. Wobble 9 Earth, Wind & Fire September 10 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 11 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 ABBA Dancing Queen 14 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 15 Outkast Hey Ya! 16 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 17 Kenny Loggins Footloose 18 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Spice Girls Wannabe 21 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 22 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 23 Bruno Mars Marry You 24 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 25 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 26 B-52's Love Shack 27 Killers Mr. Brightside 28 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 29 Dan + Shay Speechless 30 Flo Rida Feat. T-Pain Low 31 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 32 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 33 Isley Brothers Shout 34 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 35 Luke Combs Beautiful Crazy 36 Ed Sheeran Perfect 37 Nelly Hot In Herre 38 Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Ain't No Mountain High Enough 39 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 40 'N Sync Bye Bye Bye 41 Lil Nas X Feat. -

San Francisco, CA II June 5-6, 2021

San Francisco, CA II June 5-6, 2021 Top Select Junior Solo 1 - Sofia Martin - Next - Capitol Dance Company Top Select Teen Solo 1 - Rebecca Rebello - Forever Your Girl - Capitol Dance Company 2 - Quillan Casem - Crazy - Dance Academy USA 3 - Gracie Lee - Marathon - Dance Academy USA 4 - Siena Dunn - Volcanic - Dance Academy USA 5 - Sydney Zerbini - Feeling Good - Infinity Dance Studio Top Select Senior Solo 1 - Cheryl Yeh - Swan - Capitol Dance Company 2 - Sydney Shigemoto - Raindance - Capitol Dance Company 3 - Cecilia Sun - Running - Dance Academy USA 4 - Emily Rosa - Try A Little Tenderness - Capitol Dance Company 5 - Skye Casem - Lilac Wine - Dance Academy USA 6 - Sydney Hirai - Ulysses' Gaze - Dance Academy USA 7 - Kacey Ura - Kissing You - Capitol Dance Company 8 - Emma Zilger - 9 Crimes - West Valley Dance Company 9 - Alessandra Smith - Copycat - West Valley Dance Company 10 - Lindsay Loventhal - My Type - Capitol Dance Company 11 - Dylan Washington - Crumbling - Dance Academy USA 12 - Sarah Woodrow - Big Girls Cry - West Valley Dance Company 13 - Ava Salvador - Gotta Get Through This - Dance Academy USA 14 - Shana Zheng - The Closing - Dance Academy USA 15 - Marcello Salvatierra - Wicked Games - West Valley Dance Company Top Select Teen Duet/Trio 1 - Yikes - West Valley Dance Company - Shannon Claude 2 - Storm - Infinity Dance Studio - Top Select Senior Duet/Trio 1 - You Go I Go - Capitol Dance Company - Allison Fields 2 - Flames - West Valley Dance Company - Shannon Claude 3 - Baby Did A Bad, Bad Thing - West Valley Dance Company -

People & Places NEWS/FEATURES

ARAB TIMES, TUESDAY, MAY 25, 2021 NEWS/FEATURES 13 People & Places Music ‘Celebrated & appreciated’ Saweetie grateful to be just ‘nominated’ LOS ANGELES, May 24, (AP): Platinum-selling rap- per Saweetie has incorporated choreography in her live performances, but ask her about working with controversial music producer Dr. Luke and she dances around the question like a principal ballerina. Dr. Luke, who has been embattled in a lawsuit with artist Kesha since 2014, has produced Saweetie’s lat- est hits — the bops “Tap In” and “Best Friend.” The songs have reached the Top 10 and Top 20 on rap and pop charts, respectively, and the success helped Saweetie score a top female rap artist nomination at the Billboard Music Awards, pitting her against Grammy-winners Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion. Dr. Luke marked a major comeback last year, scoring his fi rst No. 1 hit since 2014 with “Say So” by Doja Cat, who is signed to his label and is featured on Saweetie’s “Best Friend.” Once ousted from the industry, Dr. Luke has resurged on the charts in a big way, also producing and writing for acts In this video image provided by NBC, BTS performs during the Billboard Music Awards on May 23. (AP) like Juice WRLD, DaBaby, Lil Wayne, Kygo, The Kid Laroi Saweetie and Tay Money. This year he even earned his fi rst Grammy nomination in seven years and he’s up for producer of the year at next week’s iHeartRadio Music Awards. In an interview with The Associated Press on last Thursday, Saweetie talks about her success, her debut album and, reluctantly, Dr. -

Findings from a Two-Year Examination of Teacher Engagement in TAP Schools Across Louisiana

Findings from a Two-Year Examination of Teacher Engagement in TAP Schools across Louisiana Prepared for National Institute for Excellence in Teaching By Dale Mann, Ph.D., Trevor Leutscher, Ph.D. R. Martin Reardon, Ph.D. September 2013 Findings from a Two-Year Examination of Teacher Engagement in TAP Schools across Louisiana Table of Contents 1.0 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 5 2.0 Introduction and Background................................................................................................................ 11 3.0 Summary of Evaluation Design ............................................................................................................ 12 3.1 Study Design .................................................................................................................................... 12 3.2 Study Sites and Sampling ................................................................................................................. 13 4.0 Methods................................................................................................................................................. 15 4.1. Data Collection Instruments ............................................................................................................. 15 4.1.1 Web-surveys .............................................................................................................................. 15 4.1.2 Random-interval -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

Bullets High Five

DUC REDAKTION Hofweg 61a · D-22085 Hamburg T 040 - 369 059 0 WEEK 40 [email protected] · www.trendcharts.de 24.09.2020 Approved for publication on Tuesday, 29.09.2020 THIS LAST WEEKS IN PEAK WEEK WEEK CHARTS ARTIST TITLE LABEL/DISTRIBUTOR POSITION 01 01 03 Pharrell Williams Ft. JAY-Z Entrepreneur Columbia/Sony 01 02 NEW Usher Bad Habits RCA/Sony 02 03 04 06 Jawsh 685 x Jason Derulo Savage Love Columbia/Sony 03 04 07 05 Drake Ft. Lil Durk Laugh Now Cry Later OVO/Republic/UMI/Universal 01 05 NEW G-Eazy Ft. Mulatto Down RCA/Sony 05 06 03 07 A$AP Ferg Ft. Nicki Minaj & MadeinTYO Move Ya Hips RCA/Sony 02 07 09 04 24kGoldn Ft. Iann Dior Mood Columbia/Sony 07 08 02 06 Cardi B Ft. Megan Thee Stallion WAP Atlantic/WMI/Warner 01 09 08 03 Calvin Harris Ft. The Weeknd Over Now Columbia/Sony 08 10 14 03 Saweetie Ft. Post Malone, DaBaby & Jack Harlow Tap In (Remix) ICY/Artistry/WMI/Warner 09 11 05 04 Capital Bra x Cro Frühstück In Paris Bra Musik/Urban/VEC/Universal 05 12 06 10 Tyga Ibiza Last Kings/Columbia/Sony 01 13 24 02 > Octavian Ft. Gunna & SAINt JHN Famous Black Butter/Sony 13 14 20 07 Juicy J Ft. Wiz Khalifa Gah Damn High Trippy/eOne 05 15 NEW Daddy Yankee, Anuel AA & Kendo Kaponi Don Don El Cartel/UMI/Universal 15 16 10 04 Bausa & Juju 2.012 Downbeat/Warner Germany/WMD/Warner 10 17 15 06 KitschKrieg & Jamule Unterwegs SoulForce/BMG Rights/ADA 13 18 17 09 DJ Khaled Ft. -

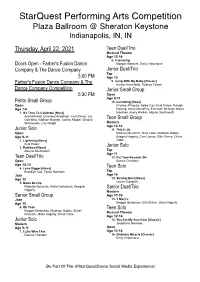

Competition Program!

StarQuest Performing Arts Competition Plaza Ballroom @ Sheraton Keystone Indianapolis, IN, IN Thursday, April 22, 2021 Teen Duet/Trio Musical Theatre Age 12-14 8. Friendship Doors Open - Farber's Fusion Dance Morgan Albrecht, Emily Imbornone Company & The Dance Company Junior Duet/Trio Tap 5:00 PM Age 10 9. Jump With My Baby [Classic] Farber's Fusion Dance Company & The Hunter Annandale, Sydney Fessel Dance Company Competition Junior Small Group 5:30 PM Open Age 9-11 Petite Small Group 10. Levitating [Nova] Open Charlee Althouse, Addie Cox, Kyla Enlow, Ryleigh Age 7-8 Maharg, Alexa Mccaffrey, Emerson Mchugh, Mazie 1. It's Time To Celebrate [Nova] Morrison, Avery Rankin, Alayna Southworth Ariel Allwardt, Emerson Anderson, Cora Dixon, Lily Gambino, Addison Hackett, Collins Klippel, Victoria Teen Small Group Wachowski, Livy Wright Modern Age 12-14 Junior Solo 11. This Is Us Open Madelyn Beuchler, Desi Cook, Madison Dobbs, Age 9-11 Keegan Hagerty, Cami Jones, Ellie Ohime, Olivia 2. Lightning [Nova] Tuttle Kyla Enlow 3. Rainbow [Nova] Junior Solo Alayna Southworth Tap Age 11 Teen Duet/Trio 12. Put Your Records On Open Danica Chandler Age 12-14 4. Lone Digger [Nova] Teen Solo Brooklyn Cox, Taylor Morrison Tap Jazz Age 14 Age 13 13. Sunday Best [Nova] 5. Gotta Get Up Lauren Golightly Madelyn Beuchler, Hazel Derloshon, Keegan Senior Duet/Trio Hagerty Modern Senior Small Group Age 17-19 Jazz 14. 3 Mary's Age 15 Maggie Derloshon, Ella Divish, Jillian Hagerty 6. Oh Yeah Teen Solo Maggie Derloshon, Madison Dobbs, Skyler Musical Theatre Greulich, Jillian Hagerty, Olivia Tuttle Age 12-14 Junior Solo 15. -

Celebrating Indiana's 125+ Craft Breweries

THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE BREWERS OF INDIANA GUILD BREWS CRUISE! Seven weekend brewery road trips you’ll love PG. 25 Cheers! CELEBRATING INDIANA’S 125+ CRAFT BREWERIES BOTTOMS UP! Visit every hop shop in Indiana PG. 39 INSIDER BEHIND THE BEER AT INDY’S ST. JOSEPH TOP GEAR BUZZ-WORTHY BUYS HOW TO MAKE IT YOUR BEST BREW FEST YET! drinkIN.beer $4.95 DrinkIN CHEERS! THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE BREWERS OF INDIANA GUILD PUBLISHER The Brewers of Indiana Guild in conjunction with Emmis Communications THE BREWERS OF INDIANA GUILD BOARD OF DIRECTORS PRESIDENT Greg Emig, Lafayette Brewing Company VICE PRESIDENT Ted Miller*, Outliers Brewing, Brugge Brasserie TREASURER DJ McCallister, Black Swan Brewpub SECRETARY Justin Miller, Black Acre Brewing Co. BOARD Nick Davidson, Tin Man Brewing Company Jeff Eaton, Barley Island Brewing Company Kaitlyn Hendricks, Three Floyds Brewing Company John Hill*, Broad Ripple Brewpub Jon Lang, Triton Brewing Company Steve Llewellyn, Function Brewing HANK YOU FOR PICKING UP THE INAUGURAL Will Moorman, Tow Yard Brewers of Indiana Guild magazine. We are proud Brewing Company Brian Nentrup, Hoosier to have brought this official Indiana beer guide to Brewing Company fruition. Shane Pearson, Daredevil Brewing Co. For 16 years, the Brewers of Indiana Guild has Clay Robinson*, Sun King worked as an advocate for brewers around the state. Brewery T Our mission has always been to promote public Blaine Stuckey*, Mad Anthony Brewing Company awareness and appreciation for the award-winning variety of beer produced David Yancey, Taxman in Indiana, and we believe that this publication is another step in furthering Brewing Company that mission.