Peter and the Starcatcher Production Handbook Is Here to Guide You Through All Aspects of Production: from Casting to Rehearsal to Design and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KMP LIST E:\New Songs\New Videos\Eminem\ Eminem

_KMP_LIST E:\New Songs\New videos\Eminem\▶ Eminem - Survival (Explicit) - YouTube.mp4▶ Eminem - Survival (Explicit) - YouTube.mp4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\blame it on me.mpgblame it on me.mpg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\I Just had.mp4I Just had.mp4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon\Shut It Down.flvShut It Down.flv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\03. I Just Had Sex (Ft. Akon) (www.SongsLover.com). mp303. I Just Had Sex (Ft. Akon) (www.SongsLover.com).mp3 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon - mr lonely(2).mpegakon - mr lonely(2).mpeg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon - Music Video - Smack That (feat. eminem) (Ram Videos).mpgAkon - Music Video - Smack That (feat. eminem) (Ram Videos).mpg E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon - Right Now (Na Na Na) - YouTube.flvAkon - Righ t Now (Na Na Na) - YouTube.flv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon Ft Eminem- Smack That-videosmusicalesdvix.blog spot.com.mkvAkon Ft Eminem- Smack That-videosmusicalesdvix.blogspot.com.mkv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft Snoop Doggs - I wanna luv U.aviAkon ft Snoop Doggs - I wanna luv U.avi E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft. Dave Aude & Luciana - Bad Boy Official Vid eo (New Song 2013) HD.MP4Akon ft. Dave Aude & Luciana - Bad Boy Official Video (N ew Song 2013) HD.MP4 E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\Akon ft.Kardinal Offishall & Colby O'Donis - Beauti ful ---upload by Manoj say thanx at [email protected] ft.Kardinal Offish all & Colby O'Donis - Beautiful ---upload by Manoj say thanx at [email protected] om.mkv E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\akon-i wanna love you.aviakon-i wanna love you.avi E:\New Songs\New videos\Akon\David Guetta feat. -

The New Yorker

Kindle Edition, 2015 © The New Yorker COMMENT SEARCH AND RESCUE BY PHILIP GOUREVITCH On the evening of May 22, 1988, a hundred and ten Vietnamese men, women, and children huddled aboard a leaky forty-five-foot junk bound for Malaysia. For the price of an ounce of gold each—the traffickers’ fee for orchestrating the escape—they became boat people, joining the million or so others who had taken their chances on the South China Sea to flee Vietnam after the Communist takeover. No one knows how many of them died, but estimates rose as high as one in three. The group on the junk were told that their voyage would take four or five days, but on the third day the engine quit working. For the next two weeks, they drifted, while dozens of ships passed them by. They ran out of food and potable water, and some of them died. Then an American warship appeared, the U.S.S. Dubuque, under the command of Captain Alexander Balian, who stopped to inspect the boat and to give its occupants tinned meat, water, and a map. The rations didn’t last long. The nearest land was the Philippines, more than two hundred miles away, and it took eighteen days to get there. By then, only fifty-two of the boat people were left alive to tell how they had made it—by eating their dead shipmates. It was an extraordinary story, and it had an extraordinary consequence: Captain Balian, a much decorated Vietnam War veteran, was relieved of his command and court- martialled, for failing to offer adequate assistance to the passengers. -

History of the Commonwealth Games

GAMES HISTORY INTRODUCTION In past centuries, the British Empire’s power and influence stretched all over the world. It started at the time of Elizabeth 1 when Sir Francis Drake and other explorers started to challenge the Portuguese and Spanish domination of the world. The modern Commonwealth was formed in 1949, with ‘British’ dropped from the name and with Logo of the Commonwealth many countries becoming independent, but Games Federation choosing to remain part of the group of nations called the Commonwealth. The first recorded Games between British Empire athletes were part of the celebrations for the Coronation of His Majesty King George V in 1911. The Games were called the 'Festival of Empire' and included Athletics, Boxing, Wrestling and Swimming events. At the 1928 Olympic Games in Amsterdam, the friendliness between the Empire athletes revived the idea of the Festival of Empire. Canadian, Bobby Robinson, called a meeting of British Empire sports representatives, who agreed to his proposal to hold the first Games in 1930 in Hamilton, Canada. From 1930 to 1950 the Games were called the British Empire Games, and until 1962 were called the British Empire and Commonwealth Games. From 1966 to 1974 they became the British Commonwealth Games and from 1978 onwards they have been known as the Commonwealth Games. HISTORY OF THE COMMONWEALTH GAMES 1930 British Empire Games Hamilton, Canada 16-23 August The first official Commonwealth Games, held in Hamilton, Canada in 1930 were called the British Empire Games. Competing Countries (11) Australia, Bermuda, British Guiana (now Guyana), Canada, England, Newfoundland (now part of Canada), New Zealand, Northern Ireland, Scotland, South Africa and Wales. -

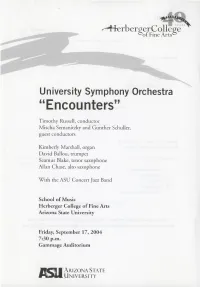

University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters"

FierbergerCollegeYEARS of Fine Arts University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters" Timothy Russell, conductor Mischa Semanitzky and Gunther Schuller, guest conductors Kimberly Marshall, organ David Ballou, trumpet Seamus Blake, tenor saxophone Allan Chase, alto saxophone With the ASU Concert Jazz Band School of Music Herberger College of Fine Arts Arizona State University Friday, September 17, 2004 7:30 p.m. Gammage Auditorium ARIZONA STATE M UNIVERSITY Program Overture to Nabucco Giuseppe Verdi (1813 — 1901) Timothy Russell, conductor Symphony No. 3 (Symphony — Poem) Aram ifyich Khachaturian (1903 — 1978) Allegro moderato, maestoso Allegro Andante sostenuto Maestoso — Tempo I (played without pause) Kimberly Marshall, organ Mischa Semanitzky, conductor Intermission Remarks by Dean J. Robert Wills Remarks by Gunther Schuller Encounters (2003) Gunther Schuller (b.1925) I. Tempo moderato II. Quasi Presto III. Adagio IV. Misterioso (played without pause) Gunther Schuller, conductor *Out of respect for the performers and those audience members around you, please turn all beepers, cell phones and watches to their silent mode. Thank you. Program Notes Symphony No. 3 – Aram Il'yich Khachaturian In November 1953, Aram Khachaturian acted on the encouraging signs of a cultural thaw following the death of Stalin six months earlier and wrote an article for the magazine Sovetskaya Muzika pleading for greater creative freedom. The way forward, he wrote, would have to be without the bureaucratic interference that had marred the creative efforts of previous years. How often in the past, he continues, 'have we listened to "monumental" works...that amounted to nothing but empty prattle by the composer, bolstered up by a contemporary theme announced in descriptive titles.' He was surely thinking of those countless odes to Stalin, Lenin and the Revolution, many of them subdivided into vividly worded sections; and in that respect Khachaturian had been no less guilty than most of his contemporaries. -

Facultad De Filosofía Y Letras Título Del

CURSO 2018-2019 Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Grado en Periodismo Título del TFG LA PERSONALIDAD DEL PETER PAN ORIGINAL EN LA LITERATURA Y LA CONCEPCIÓN SIMPLIFICADA DEL PERSONAJE EN EL IMAGINARIO COLECTIVO Alumno: Juan Eguren Paredes Tutora: Nereida López Vidales 1 2 RESUMEN Arrastrados por la cultura multimedia, generaciones enteras han disfrutado y mitificado iconos de la gran pantalla sin conocer las verdaderas intenciones de su autor original. Peter Pan es un ejemplo de ello y su personalidad fue fruto de su época, en el Londres de principios del siglo XX. Sus rasgos influenciados por personajes mitológicos y experiencias de su creador, James M. Barrie, se perdieron con la adaptación que lo hizo mundialmente famoso. Disney le dio el éxito y blanqueó aspectos de Pan que, aun así, han trascendido al imaginario colectivo llegando a considerar a “Peter Pan” como un adulto que no quiere afrontar responsabilidades. Este estudio pretende analizar la personalidad escogida por Barrie así como sus diferentes obras con él como protagonista y el poso cultural restante a día de hoy pasando por el “síndrome” tan frecuentemente mencionado. Esto supondrá no sólo el análisis de las tres obras escritas por el escocés que le mencionan explícitamente, sino también la contextualización de Neverland o El País de Nunca Jamás, la descripción de un “Peter Pan” hoy en día, tal y como lo presentan estudios en psicología, y un resumen final como comparativa de las diferentes cualidades atribuidas al personaje. Además, se incluirán algunas referencias a alguna adaptación cinematográfica y la historia que llevó a Barrie al diseño del personaje tal y como se puede disfrutar en su literatura. -

The University of Chicago Objects of Veneration

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OBJECTS OF VENERATION: MUSIC AND MATERIALITY IN THE COMPOSER-CULTS OF GERMANY AND AUSTRIA, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY ABIGAIL FINE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 © Copyright Abigail Fine 2017 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES.................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................ ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................. x ABSTRACT....................................................................................................... xiii INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: Beethoven’s Death and the Physiognomy of Late Style Introduction..................................................................................................... 41 Part I: Material Reception Beethoven’s (Death) Mask............................................................................. 50 The Cult of the Face........................................................................................ 67 Part II: Musical Reception Musical Physiognomies............................................................................... -

The Mercurian

The Mercurian : : A Theatrical Translation Review Volume 4, Number 4 Editor: Adam Versényi Editorial Assistant: Michaela Morton The Mercurian is named for Mercury who, if he had known it, was/is the patron god of theatrical translators, those intrepid souls possessed of eloquence, feats of skill, messengers not between the gods but between cultures, traders in images, nimble and dexterous linguistic thieves. Like the metal mercury, theatrical translators are capable of absorbing other metals, forming amalgams. As in ancient chemistry, the mercurian is one of the five elementary “principles” of which all material substances are compounded, otherwise known as “spirit”. The theatrical translator is sprightly, lively, potentially volatile, sometimes inconstant, witty, an ideal guide or conductor on the road. The Mercurian publishes translations of plays and performance pieces from any language into English. The Mercurian also welcomes theoretical pieces about theatrical translation, rants, manifestos, and position papers pertaining to translation for the theatre, as well as production histories of theatrical translations. Submissions should be sent to: Adam Versényi at [email protected] or by snail mail: Adam Versényi, Department of Dramatic Art, CB# 3230, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3230. For translations of plays or performance pieces, unless the material is in the public domain, please send proof of permission to translate from the playwright or original creator of the piece. Since one of the primary objects of The Mercurian is to move translated pieces into production, no translations of plays or performance pieces will be published unless the translator can certify that he/she has had an opportunity to hear the translation performed in either a reading or another production-oriented venue. -

“Canned History”: American Newsreels and The

“Canned History”: American Newsreels and the Commodification of Reality, 1927-1945 By Joseph E.J. Clark B.A., University of British Columbia, 1999 M.A., University of British Columbia, 2001 M.A., Brown University, 2004 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of American Civilization at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May, 2011 © Copyright 2010, by Joseph E.J. Clark This dissertation by Joseph E.J. Clark is accepted in its present form by the Department of American Civilization as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Susan Smulyan, Co-director Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Philip Rosen, Co-director Recommended to the Graduate Council Date:____________ _________________________________ Professor Lynne Joyrich, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date:____________ _________________________________ Dean Peter Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae Joseph E.J. Clark Date of Birth: July 30, 1975 Place of Birth: Beverley, United Kingdom Education: Ph.D. American Civilization, Brown University, 2011 Master of Arts, American Civilization, Brown University, 2004 Master of Arts, History, University of British Columbia, 2001 Bachelor of Arts, University of British Columbia, 1999 Teaching Experience: Sessional Instructor, Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies, Simon Fraser University, Spring 2010 Sessional Instructor, Department of History, Simon Fraser University, Fall 2008 Sessional Instructor, Department of Theatre, Film, and Creative Writing, University of British Columbia, Spring 2008 Teaching Fellow, Department of American Civilization, Brown University, 2006 Teaching Assistant, Brown University, 2003-2004 Publications: “Double Vision: World War II, Racial Uplift, and the All-American Newsreel’s Pedagogical Address,” in Charles Acland and Haidee Wasson, eds. -

T H E P Ro G

Friday, February 1, 2019 at 8:30 pm m a r Jose Llana g Kimberly Grigsby , Music Director and Piano o Aaron Heick , Reeds r Pete Donovan , Bass P Jon Epcar , Drums e Sean Driscoll , Guitar h Randy Andos , Trombone T Matt Owens , Trumpet Entcho Todorov and Hiroko Taguchi , Violin Chris Cardona , Viola Clarice Jensen , Cello Jaygee Macapugay , Jeigh Madjus , Billy Bustamante , Renée Albulario , Vocals John Clancy , Orchestrator Michael Starobin , Orchestrator Matt Stine, Music Track Editor This evening’s program is approximately 75 minutes long and will be performed without intermission. Please make certain all your electronic devices are switched off. Lead support provided by PGIM, the global investment management businesses of Prudential Financial, Inc. Endowment support provided by Bank of America This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Steinway Piano The Appel Room Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Frederick P. Rose Hall American Songbook Additional support for Lincoln Center’s American Songbook is provided by Rita J. and Stanley H. Kaplan Family Foundation, The DuBose and Dorothy Heyward Memorial Fund, The Shubert Foundation, Great Performers Circle, Lincoln Center Spotlight, Chairman’s Council, and Friends of Lincoln Center Public support is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature Nespresso is the Official Coffee of Lincoln Center NewYork-Presbyterian is the Official Hospital of Lincoln Center Artist catering provided by Zabar’s and Zabars.com UPCOMING AMERICAN SONGBOOK EVENTS IN THE APPEL ROOM: Saturday, February 2 at 8:30 pm Rachael & Vilray Wednesday, February 13 at 8:30 pm Nancy And Beth Thursday, February 14 at 8:30 pm St. -

Karaoke Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #9 Dream Lennon, John 1985 Bowling For Soup (Day Oh) The Banana Belefonte, Harry 1994 Aldean, Jason Boat Song 1999 Prince (I Would Do) Anything Meat Loaf 19th Nervous Rolling Stones, The For Love Breakdown (Kissed You) Gloriana 2 Become 1 Jewel Goodnight 2 Become 1 Spice Girls (Meet) The Flintstones B52's, The 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The (Reach Up For The) Duran Duran 2 Faced Louise Sunrise 2 For The Show Trooper (Sitting On The) Dock Redding, Otis 2 Hearts Minogue, Kylie Of The Bay 2 In The Morning New Kids On The (There's Gotta Be) Orrico, Stacie Block More To Life 2 Step Dj Unk (Your Love Has Lifted Shelton, Ricky Van Me) Higher And 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc Higher 2001 Space Odyssey Presley, Elvis 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 24 Jem (M-F Mix) 24 7 Edmonds, Kevon 1 Thing Amerie 24 Hours At A Time Tucker, Marshall, 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) Plain White T's Band 1,000 Faces Montana, Randy 24's Richgirl & Bun B 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys 25 Miles Starr, Edwin 100 Years Five For Fighting 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The 10th Ave Freeze Out Springsteen, Bruce 26 Miles Four Preps, The 123 Estefan, Gloria 3 Spears, Britney 1-2-3 Berry, Len 3 Dressed Up As A 9 Trooper 1-2-3 Estefan, Gloria 3 Libras Perfect Circle, A 1234 Feist 300 Am Matchbox 20 1251 Strokes, The 37 Stitches Drowning Pool 13 Is Uninvited Morissette, Alanis 4 Minutes Avant 15 Minutes Atkins, Rodney 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin 15 Minutes Of Shame Cook, Kristy Lee Timberlake 16 @ War Karina 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake & 16th Avenue Dalton, Lacy J. -

Melbourne 2006 Commonwealth Games: Implications for the Local Property Market

The Melbourne 2006 Commonwealth Games: implications for the local property market Richard Reed* and Hao Wu (*contact author) Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning University of Melbourne Melbourne 3010 Victoria Australia Tel: +61 3 8344 8966 Fax: +61 3 8344 5532 Email: [email protected] Abstract for the 11th Annual Pacific Rim Real Estate Conference 23 - 27 January 2005 - Melbourne, Australia Keywords: Commonwealth games, major sporting event, infrastructure, property market, host city. Abstract: In 2006 Melbourne will host the 18th Commonwealth Games with Brisbane being the last Australian city to host this event over two decades ago in 1982. Melbourne has not held a major global sporting event since the 1956 Olympic Games, although the 2006 Commonwealth Games follows on from the successful 2000 Sydney Olympics. These sporting events have continued to grow from strength to strength, and have been assisted by Australia's close affiliation with sport and the widespread global media coverage. In a similar manner to other sporting events that Melbourne hosts, including the Australian Tennis Open, Formula One Grand Prix, Motorcycle Grand Prix, Melbourne Cup and Australian Football League, the city and its inhabitants are consumed by these events. The 2006 Commonwealth Games is certain to follow this trend. The task of hosting the Commonwealth Games is enormous, although actively pursued in a fierce bidding process by competing cities. The benefits are undisputed and include an influx of visitors to the host city, an opportunity to enhance or rebuild infrastructure such as transport, plus the worldwide focus on the host city before and during the event. -

Madonna MP3 Collection - Madonna Part 2 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Madonna MP3 Collection - Madonna Part 2 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Hip hop / Pop Album: MP3 Collection - Madonna Part 2 Country: Russia Released: 2012 Style: House, Synth-pop, Ballad, Electro, RnB/Swing, Electro House MP3 version RAR size: 1708 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1392 mb WMA version RAR size: 1865 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 427 Other Formats: APE MP2 RA MP1 TTA VOX XM Tracklist Hide Credits Beautiful Stranger (Single) - 1999 1-1 Beautiful Stranger 4:24 1-2 Beautiful Stranger (Remix) 10:15 1-3 Beautiful Stranger (Mix) 4:04 Ray Of Light (Remix Album) - 1999 1-4 Ray Of Light (Ultra Violet Mix) 10:46 Drowned World (Substitut For Love (Bt And Sashas Remix) 1-5 9:28 Remix – Bt, Sasha Sky Fits Heaven (Sasha Remix) 1-6 7:22 Remix – Sasha Power Of Goodbay (Luke Slaters Filtered Mix) 1-7 6:09 Remix – Luke Slater 1-8 Candy Perfume Girl (Sasha Remix) 4:52 1-9 Frozen (Meltdown Mix - Long Version 8:09 1-10 Nothing Really Matters (Re-funk-k-mix) 4:23 Skin (Orbits Uv7 Remix) 1-11 8:00 Remix – Orbit* Frozen (Stereo Mcs Mix) 1-12 5:48 Remix – Stereo Mcs* 1-13 Bonus - What It Feels Like For A Girl (remix) 9:50 1-14 Bonus - Dont Tell Me (remix) 4:26 American Pie (Single) - 2000 1-15 American Pie (Album Version) 4:35 American Pie (Richard Humpty Vission Radio Mix) 1-16 4:30 Remix – Richard Humpty Vission* American Pie (Richard Humpty Vission Visits Madonna) 1-17 5:44 Remix – Richard Humpty Vission* Music - 2000 1-18 Music 3:45 1-19 Impressive Instant 3:38 1-20 Runaway Lover 4:47 1-21 I Deserve It 4:24 1-22 Amazing 3:43