The Ttab's Strict Standard for Fraud for Trademark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guía Profesional 2017 • 12€ Guía Profesional 2017 Profesional Guía

GUÍA PROFESIONAL 2017 • 12€ GUÍA PROFESIONAL 2017 PROFESIONAL GUÍA MAMADEDE F RFOM R OM RE RECYCCYCLELED D MAMADEDE F RFOM R OM RE RECYCCYCLELED D BEBEMAACHACHDE PLASTICF PLASTIC R OM RECYC LED BEBEACHACH PLASTIC PLASTIC BEACH PLASTIC O NEIO NEILL.COLL.COM/BM/BLUELUE O NEIO NEILL.COLL.COM/BM/BLUELUE O NEILL.CO M/BLUE GUÍA PROFesiOnal www.diffusionsport.com EDITA Peldaño 5 | 6 Direcciones de interés 5 Cadenas comerciales DIRECTOR DEL ÁREA 6 Grupos de compra DE DEPORTE Jordi Vilagut 7 Empresas [email protected] 69 Marcas colABORADOR José Mª Collazos índice de publicidad PUBLICIDAD Atmósfera Sport ........................................................................... 39 Pablo Prieto [email protected] Chiruca .............................................................................................. 43 Dare 2b ............................................................................................. 47 IMAGEN Y DISEÑO DS Multicanalidad ......................................................................... 63 Eneko Rojas DS Newsletter ............................................................................... 51 DS Suscripción ............................................................................... MAQUETACIÓN 68 Miguel Fariñas DS Web .............................................................................................. 59 Débora Martín FBO ...................................................................................................... 31 Verónica Gil Cristina Corchuelo Happy Dance ................................................................................. -

NIKE Inc. STRATEGIC AUDIT & CORPORATE

NIKE Inc. STRATEGIC AUDIT & CORPORATE A Paper Presented as a Final Requirement in STRAMA-18 -Strategic Management Prepared by: IGAMA, ERICA Q. LAPURGA, BIANCA CAMILLE M. PIMENTEL, YVAN YOULAZ A. Presented to: PROF. MARIO BRILLANTE WESLEY C. CABOTAGE, MBA Subject Professor TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. I. Executive Summary ……………………………………………………………………...……1 II. Introduction …………………………………………………………………………...………1 III. Company Overview ………………………………………………………………………….2 A. Company Name and Logo, Head Office, Website …………………………...……………2 B. Company Vision, Mission and Values……………………………………………….…….2 C. Objectives …………………………………………………………………………………4 D. Organizational Structure …………………………………………………….…………….4 E. Corporate Governance ……………………………………………………………….……6 1. Board of Directors …………………………………………………………….………6 2. CEO ………………………………………………………………….………….……6 3. Ownership and Control ………………………………………………….……………6 F. Corporate Resources ………………………………………………………………...……9 1. Marketing ……………………………………………………………………….….…9 2. Finance ………………………………………………………………………………10 3. Research and Development ………………………………………………….………11 4. Operations and Logistics ……………………………………………………….……13 5. Human Resources ……………………………………………………...……………14 6. Information Technology ……………………………………………………….……14 IV. Industry Analysis and Competition ...……………………………...………………………15 A. Market Share Analysis ………………………………………………………...…………15 B. Competitors’ Analysis ………………………………………………………...…………16 V. Company Situation.………… ………………………………………………………….……19 A. Financial Performance ………………………………………………………………...…19 B. Comparative Analysis……………………… -

Indecision Apparent on City Income

HO AG- AND SJONS .BOOK BIDDERS 3 PAPERS 5PRINGPORT, MICH. 49284 Bond issue vitally affects elementary schools Forty members of a 110-member citizens committee used for blacktopping the play areas, providing fencing at all bond issue. School officials pointed out that higher-than- development, leaving little or nothing for 'landscaping and which worked on the 1966 school bond issue drive got a detailed schools and for seeding and landscaping. exppcted costs in the development of sewers (storm and finishing the lawn and play areas. look last week at the progress of the building program—and sanitary), street blacktop and curb and gutter and sidewalk, on The bus storage shelter would cost about $17,500, school why additional money is needed to finish it up. THE BALANCE OFTHE$250,000wouldbeusedfor several Sickles Street and the school sharing in the cost of renovation officials said. It would consist of two facing three-sided and The problem, school administrators pointed out, is that purposes, including site development at the high school, capital of a city sewer on Railroad Street has .already taken about covered shelters in which the school's 36-bus fleet would be building costs have run about $250,000 above what had been ized interest and bonding costs, contingenciesandabus storage $52,000 of the original $60,000. parked when not in use. The shelter buildings would be built anticipated in the original bond issue of $5.4 million; . shelter (which wasn't involved in the original bond issue). where the buses are presently parked.. The school board has scheduled a special election for The high school site development portion of the new bond If more money is notavailable,the $52,000will of necessity THE FURNITURE AND EQUIPMENT FOR the rural Nov. -

Adidas, Puma, Nike

The football marketing blog Subscribe to feed Home About Me My Football Lounge out there My blogroll IMAGE OF THE DAY adidas, Puma, Nike: a sport legacy September 15, 2010 in Sponsorship | Tags: Puma, adidas, Nike, Zidane, World Cup, Umbro, Major League Soccer, Usain Bolt, Herbert Hainer, LeBron James, Lance Armstrong, Tiger Woods, Michael Johnson, adidas-Salomon AG, Bill Bowerman, Hurley International, Converse, Ferrari, Phil Knight, Stella Mc Cartney, Reebok, Volvo Ocean race, September 21 day of peace Hi everyone, This sport chronological trilogy has triggered a massive traffic Anelka sent a message to and I thank every single one of you for stopping by. Today, the FFF the last chapter is called “adidas, Puma, Nike: a sport legacy”. These brands are fully established sports brands and have inspired other brands to tap into the sport industry. They left CATEGORIES a legacy or heritage not only to themselves but to other brands that have now models to get inspiration from. From 2010 FIFA World Cup (41) 1996 until today, adidas, Puma and Nike have grown significantly with fantastic 2018-2022 World Cup bid (9) athletes by their sides. Champions League (8) Clubs (12) Here we go: Do you know football? (3) General (9) adidas, Puma, Nike: a sport legacy Players (6) Sponsorship (29) 1996 - adidas outfits 33 nations & 600 participants during the Atlanta Olympic Games. Adidas supplies products for 21 of the 26 sports AND the official Karl Lusbec matchball and equips the referees and linesmen at UEFA European Championships. The German team wins fully outfitted with adidas. - adidas signs an exclusive sponsorship deal with the MLS - Nike signs Tiger Woods soon after he gives up his amateur golf status. -

IGP Park Council Ieyes Demolition of Old Landmark

Home 01 t,"e New, All the News of All the Pointes Every Thursday Morning rosse Pointe' ews Complete News Coverage of All the Pointes Vol. 3o-No. 24 thEnt~red ~sfsecond Class Matler at $5.00Per Year 28 P~ges-Two Sections-Section One, ___________ .:....-=e~..:.os:.:t~.f_I_Ce_.t __ D_ctr_O_It_,_M_lch_lg_all. GROSSE POINTE, MICHIGAN, Thursday, June 12, 1969 lllePerCOpy , j @ -- IIEADLINt:S Products of Teer:"1age Talent Put on Display 'Lead Field of the IGP Park Council Of Four for WEEK School Board As Compiled by the IEyes Demolition Grosse Pointe News Candidates Backed by Citizens for Education Thursday, June 5 Of Old Landmark Victorious as 5,690 A SERIES OF BLASTS sec. Cast Ballots onds apart, rjpped through a Authorizes Solicitation of Bids to Raze McMillan' gunpowder storage area Wed. Residence in Three Mile Drive Park Unless Alfred R. Glancy, Jr. and nesday at E. I. duPont de Ne- William J. Adams led a mours and Company explosives Practical Use is Found field of four candidates to works in Carneys Point, N,J. The Park council on Monday, June 9, authorized win. two four-year terms At least three persons were killed and dozens injured. Four City Manag~rRobert Slone to solicit bids for the pos- on.the Grosse Pointe Board other employes who worked in sible razing of the McMillanmansion, except .the garage of Education in the school the storage area were reported or carriage house, on the seven.acre property, now a district's trusteeship elec- missing and at least 56 persons part of the Three Mile Drive Park. -

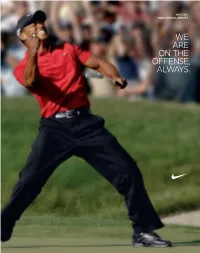

We Are on the Offense Always

NIKE, INC. 2008 ANNUAL REPORT WE ARE ON THE OFFENSE, ALWAYS. .)+%'/,&,/'/ &).!, NIKE BASKETBALL NIKE WOMEN’S TRAINING NIKE SPORTSWEAR NIKE MEN’S TRAINING NIKE FOOTBALL NIKE RUNNING I’m very pleased with how we have enhanced the position, performance, To Our Shareholders, and potential of all the When I stepped into the CEO role 2½ years ago, the leadership team reaffirmed a simple concept that I knew was true from my nearly brands and categories in 30 years of experience here – NIKE is a growth company. That fact shaped the long-term financial goals we outlined more than seven the NIKE, Inc. family. years ago. It also inspired our goal of reaching $23 billion in revenue by the end of fiscal 2011. Fiscal 2008 illustrated the power of that financial model, the strength of our team, and the ability of NIKE to bring innovative products and excitement to the marketplace. Our unique role as the innovator and leader in our industry enables us to drive consistent, long-term profitable growth. In 2008 we added $2.3 billion of incremental revenue to reach $18.6 billion – up 14 percent year over year with growth in every region and every business unit. Gross margins improved more than a percentage point to a record high of 45%, and earnings per share grew 28 percent. We increased our return on invested capital by 250 basis points1, increased dividends by 23%, and bought back $1.2 billion in stock. 2008 was a very good year. As we enter fiscal 2009 we are well-positioned for the future. -

NOTE 18 Operating Segments and Related Information

PART II Note 18 Operating Segments and Related Information counterparty, to post collateral should the fair value of outstanding derivatives of derivative instruments with credit risk related contingent features that are per counterparty be greater than $50 million. Additionally, a certain level of in a net liability position at May 31, 2011 was $160 million. The Company, or decline in credit rating of either the Company or the counterparty could trigger any counterparty, were not required to post any collateral as a result of these collateral requirements. As of May 31, 2011, the Company was in compliance contingent features. As a result of the above considerations, the Company with all such credit risk related contingent features. The aggregate fair value considers the impact of the risk of counterparty default to be immaterial. NOTE 18 Operating Segments and Related Information Operating Segments Effective June 1, 2009, the primary fi nancial measure used by the Company to evaluate performance of individual operating segments is Earnings Before The Company’s operating segments are evidence of the structure of the Interest and Taxes (commonly referred to as “EBIT”) which represents net income Company’s internal organization. The major segments are defi ned by geographic before interest expense (income), net and income taxes in the consolidated regions for operations participating in NIKE Brand sales activity excluding statements of income. Reconciling items for EBIT represent corporate expense NIKE Golf. Each NIKE Brand geographic segment operates predominantly in one items that are not allocated to the operating segments for management industry: the design, development, marketing and selling of athletic footwear, reporting. -

Definiring Van De Sportindustrie

2e Licentiaat Academiejaar 2005-2006 De productieketen van de sportindustrie: Een analyse van de sportgoederenbedrijven Eindverhandeling voorgedragen door Mario Van Dyck tot het behalen van het diploma van licentiaat in de handelswetenschappen o.l.v. Prof. Dr. Trudo Dejonghe Voor Sofie 2e Licentiaat Academiejaar 2005-2006 De productieketen van de sportindustrie: Een analyse van de sportgoederenbedrijven Eindverhandeling voorgedragen door Mario Van Dyck tot het behalen van het diploma van licentiaat in de handelswetenschappen o.l.v. Prof. Dr. Trudo Dejonghe De productieketen van de sportindustrie: Een analyse van de sportgoederenbedrijven Abstract Sinds haar ontstaan staat de sportindustrie gelijk aan big business. De pioniers onder de sportgoederenproducenten pasten reeds aan het einde van de 19e eeuw diverse marketingtechnieken toe om hun producten te verkopen, waaronder het onderschrijven van professionele atleten. De opkomst van de tv, de toegenomen participatie en de opkomst van de consumentencultuur tijdens de tweede helft van de 20e eeuw hebben dit proces alleen maar versterkt. De huidige producenten onder wie Nike en Adidas zijn over het algemeen ‘ondernemers zonder ondernemingen’. Vanuit het globale productieketenconcept kan dit verklaard worden. De kerncompetenties zoals: onderzoek en ontwikkeling, ontwerp, financiën, verkoop en marketing blijven behouden. De productie wordt uitbesteed aan onderaannemers in lagelonenlanden in de periferie en/of semi-periferie binnen het huidige wereldsysteem. Nike was één van de eerste bedrijven binnen de industrie die deze uitbestedingstechniek op grote schaal ging toepassen. De economische ontwikkelingen en de intensifiëring van de internationale handel hebben ertoe geleid dat andere spelers deze strategie eveneens zijn gaan toepassen. Verder heeft de huidige economische context tot een verzadigde westerse sportgoederenmarkt geleid. -

Australian Official Journal Of

Vol: 22 , No. 16 24 April 2008 AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS Did you know a searchable version of this journal is now available online? It's FREE and EASY to SEARCH. Find it at http://pericles.ipaustralia.gov.au/ols/epublish/content/olsEpublications.jsp or using the "Online Journals" link on the IP Australia home page. The Australian Official Journal of Designs is part of the Official Journal issued by the Commissioner of Patents for the purposes of the Patents Act 1990, the Trade Marks Act 1995 and Designs Act 2003. This Page Left Intentionally Blank (ISSN 0819-1808) AUSTRALIAN OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF TRADE MARKS 24 April 2008 Contents General Information & Notices IR means "International Registration" Amendments and Changes Application/IRs Amended and Changes ...................... 6360 Registrations/Protected IRs Amended and Changed ................ 6362 Registrations Linked ............................... 6352 Applications for Extension of Time ...................... 6359 Applications for Amendment .......................... 6360 Applications/IRs Accepted for Registration/Protection .......... 5748 Applications/IRs Filed Nos 1229677 to 1230325 ............................. 5743 Applications/IRs Lapsed, Withdrawn and Refused Lapsed ...................................... 6365 Withdrawn..................................... 6366 Refused ...................................... 6366 Assignments,TransmittalsandTransfers.................. 6366 Cancellations of Entries in Register ...................... 6374 Corrigenda..................................... -

The Oxfam Report

Labour rights and sportswear production in Asia Acknowledgements Any report of this size is a collaborative effort. The principal writers were Oxfam Australia Labour Rights Advocacy staff Tim Connor and Kelly Dent, but numerous Oxfam staff and representatives of other organisations made important contributions to the report’s development. Elena Williams, Mimmy Kowel, Sri Wulandari and other researchers conducted interviews with sportswear workers. Maureen Bathgate edited the report and arranged the design, and Martin Wurt arranged the pictures. Special thanks are particularly due to all the sportswear workers, trade union organisations, factory owners and representatives of sports brand owners who shared their experiences and perspectives through the research process. First published by Oxfam International. © Oxfam International 2006. All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holder requests that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for re-use in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the copyright holder, and a fee may be payable. Copies of this report and more information are available to download at; www.oxfam.org.au/campaigns/labour/06report. Oxfam International Suite 20, 266 Banbury Road, Oxford, OX2 7DL, UK E-mail: [email protected] Publication of this edition managed by Oxfam Australia. ISBN: 1-875 870-61-X Original language: English Authors: Tim Connor and Kelly Dent Editor: Maureen Bathgate Picture Editor: Martin Wurt Design: Paoli Smith Print: Work & Turner Make Trade Fair is a campaign by Oxfam International and its 12 affiliates, calling on governments, institutions, and multinational companies to change the rules so that trade can become part of the solution to poverty, not part of the problem. -

For Immediate Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MEDIA CONTACT: INVESTOR CONTACT: Alan Marks Pamela Catlett 503.671.4235 503.671.4589 NIKE, INC. REPORTS FISCAL 2007 EARNINGS PER SHARE OF $2.93 Revenue up 9 percent for the fiscal year and fourth quarter Fourth quarter earnings per share up 34 percent Worldwide futures orders up 12 percent BEAVERTON, Ore. (26 June, 2007) – NIKE, Inc. (NYSE:NKE) today reported financial results for the 2007 fiscal year, ended May 31, 2007. For the fiscal year, revenues grew 9 percent to $16.3 billion, compared to $15.0 billion last year. Net income increased 7 percent to $1.5 billion, compared to $1.4 billion last year, and diluted earnings per share increased 11 percent to $2.93 versus $2.64 last year. For the fourth quarter, revenues increased 9 percent to $4.4 billion, compared to $4.0 billion for the same period last year. Fourth quarter net income increased 32 percent to $437.9 million, compared to $332.8 million in the prior year, and diluted earnings per share increased 34 percent to $0.86, versus $0.64 last year. Changes in currency exchange rates increased revenue growth by 2 percentage points for the full year and fourth quarter. Commenting on results, Mark Parker, Nike, Inc. President and CEO said, “Nike is a growth company, and fiscal 2007 was no exception. We delivered another record year of revenue, earnings and cash flow. The Nike brand is extremely strong worldwide, and the Nike subsidiaries continue to increase their contribution to the performance of the company.” “Opportunities for growth at Nike have never been greater,” Parker added. -

Digital Transformation in the Sports Apparel Industry: the Case of Nike, Inc

Digital Transformation in the Sports Apparel Industry: The Case of Nike, Inc. Master Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the Degree Master of Science in Management (Entrepreneurship, Innovation & Leadership) Submitted to Prof. DDr. Arno Scharl Lukas J.M. Stangl 1521009 Vienna, 10th August 2020 I AFFIDAVIT I hereby affirm that this Master’s Thesis represents my own written work and that I have used no sources and aids other than those indicated. All passages quoted from publica- tions or paraphrased from these sources are properly cited and attributed. The thesis was not submitted in the same or in a substantially similar version, not even partially, to another examination board and was not published elsewhere. 10.08.2020 Date Signature I II ABSTRACT The global revenue of the sports apparel industry is larger than it has ever been before. Digital transformation has been a driver for the industry, leading to digital innovations within the industry. This has led to the fall of market leaders while creating opportunities for new market entrants by capturing market share through leveraging new technolo- gies. The company Nike, Inc. has been the market leader in the sports apparel industry for several decades and is known to be a forerunner in innovation. The purpose of this research is to examine how digital transformation has affected Nike, Inc. and the sports apparel industry and how it will shape the future. A secondary aim is to investigate how Nike’s customers perceive these changes and to scrutinize their digital needs and expec- tations. This research furthermore aims to conclude about the digital needs and expec- tations of Nike’s customers and if they align with Nike’s strategy.