Testimony of John Hicks Executive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digitalisation and Monetary Policy

Does the liquidity trap exist? Lhuissier, Mojon and Rubio-Ramirez AEA Congress, 4 January 2021 The views expressed here are mine and should not be attributed to the BIS Restricted “A liquidity trap may be defined as a situation in which conventional monetary policies have become impotent, because nominal interest rates are at or near zero: injecting monetary base into the economy has no effect, because base and bonds are viewed by the private sector as perfect substitutes” Paul Krugman (1998) Restricted 2 Outline 1. Motivation 2. Literature 3. Empirical analysis 4. Results 5. Discussion Restricted 3 1. Motivation: How low can long-term rates be? Central bank balance sheets1 Share of government bonds held by central banks2 % of GDP % of GDP % Restricted 4 1. Motivation: Is there a lack of monetary policy space? • Cutting down short rates and purchasing assets to cut long rates can go only so far and • the lack of “interest rate” space is very critical in several advanced economies • However, into the medium we still need to assess whether and how much MP can do when short-term rates are near the ZLB/ELB Restricted 5 Literature: The ZLB makes MP ineffective Japan . Krugman (1998) – Coenen and Wieland (2003) “John Hicks, in introducing both the IS-LM model and the liquidity trap, identified the assumption that monetary policy is ineffective, rather than the assumed downward inflexibility of prices, as the central difference between Mr. Keynes and the classics.” US and EA, before the facts . Early Fed attemps: Furher and Madigan (97); Orphanides and Williams & Reifschneider and Williams (2000) . -

Edward S. Shaw* Simon Kuznets Remarked in His Capital in The

Edward S. Shaw* Simon Kuznets remarked in his Capital in rate. There is physical wealth, its ownership The American Economy, " ... extrapolation of represented by an homogeneous financial asset inflationary pressures over the next thirty in the form of common stock or "equity," and years raises a specter of intolerable conse there is wealth in the form of real money bal quences.... "1 Fifteen of the thirty years are ances. Accumulation of physical and monetary over, and inflation has accelerated. The central wealth derives from a constant rate of saving concern of this paper is whether Kuznets' pre for the community. Inflation occurs because the diction of "intolerable consequences" for capital growth rate of nominal money exceeds the markets and capital accumulation is on track or growth rate of real money demanded. patently wrong. 2 The inflation is immaculate because its pace Monetary theory distinguishes between "im is constant and perfectly foreseen and because maculate" inflation, "clean" inflation, and the inflation tax on real money balances is com "dirty" inflation. It is the last of these that pensated precisely by a deposit-rate of interest Kuznets dreaded and that we have endured. The on money. It is fully anticipated, and it does not first section below deals very briefly with dif impose a relative penalty on the money form of ferences between the three styles of inflation. wealth. Money-wage rates rise faster than out The second section is a catalogue of ways in put prices in the degree that labor productivity which dirty inflation may obstruct and distort is growing. -

CR Traverse Analysis Progenitors & Pioneers

Traverse Analysis: Progenitors and Pioneers 14th History of Economic Thought Society of Australia Conference The University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia. 11th July 2001 Colin Richardson* School of Economics University of Tasmania ABSTRACT Traverse analysis has two progenitors (David Ricardo, Karl Marx) and five pioneers: Michal Kalecki, Adolph Lowe, Joan Robinson, J.R. Hicks, and John Hicks. Defined as the dynamic disequilibrium adjustment-path that connects an initial with a different terminal state of economic growth, the traverse comes in four “flavours”. There are neoclassical (J.R. Hicks), neo-Austrian (John Hicks), observed (Ricardo, Marx, Kalecki, Robinson), and instrumental (Lowe) traverses. These terms are explained and the seven seminal contributions are summarised and commented upon in this paper. * I am indebted to Dr Jerry Courvisanos for his supervision and comments in writing this paper. Scholarship support from The University of Tasmania is also gratefully acknowledged. 2 Introduction Nobel laureate economist Robert Solow once quipped: “The traverse is the easiest part of skiing but the most difficult part of economics”. Later, Joseph Halevi and Peter Kriesler (1992, p 225) complained that “The traverse is at the same time one of the most important concepts in economic theory, and also one of the most neglected.” This paper outlines briefly the history of economic thought between 1821 and 1973 concerning this difficult, important and neglected theoretical construct. Traverse analysis has two progenitors (David Ricardo, Karl Marx) and five pioneers: Michal Kalecki, Adolph Lowe, Joan Robinson, J.R. Hicks, and John Hicks. Defined as the dynamic disequilibrium adjustment-path that connects an initial with a different terminal state of economic growth, the traverse comes in four “flavours”. -

Unemployment Did Not Rise During the Great Depression—Rather, People Took Long Vacations

Working Paper No. 652 The Dismal State of Macroeconomics and the Opportunity for a New Beginning by L. Randall Wray Levy Economics Institute of Bard College March 2011 The Levy Economics Institute Working Paper Collection presents research in progress by Levy Institute scholars and conference participants. The purpose of the series is to disseminate ideas to and elicit comments from academics and professionals. Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, founded in 1986, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, independently funded research organization devoted to public service. Through scholarship and economic research it generates viable, effective public policy responses to important economic problems that profoundly affect the quality of life in the United States and abroad. Levy Economics Institute P.O. Box 5000 Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504-5000 http://www.levyinstitute.org Copyright © Levy Economics Institute 2011 All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Queen of England famously asked her economic advisers why none of them had seen “it” (the global financial crisis) coming. Obviously, the answer is complex, but it must include reference to the evolution of macroeconomic theory over the postwar period— from the “Age of Keynes,” through the Friedmanian era and the return of Neoclassical economics in a particularly extreme form, and, finally, on to the New Monetary Consensus, with a new version of fine-tuning. The story cannot leave out the parallel developments in finance theory—with its efficient markets hypothesis—and in approaches to regulation and supervision of financial institutions. This paper critically examines these developments and returns to the earlier Keynesian tradition to see what was left out of postwar macro. -

The Neo-Chartalist Approach to Money by L. Randall Wray

The Neo-Chartalist Approach to Money by L. Randall Wray* Working Paper No. 10 July 2000 ∗ Senior Research Associate, Center for Full Employment and Price Stability, University of Missouri-Kansas City In his interesting and important chapter, Charles Goodhart makes three main contributions. First, he argues that there are two competing approaches to the study of money, with one dominating most research and policy formation to the virtual exclusion of the other. Second, he examines and rejects Mundel’s Optimal Currency Area approach, which is based on the dominant approach to money, leading to a criticism of the theoretical basis for European Monetary Union. Finally, he introduces some historical literature on the origins of coins and money that is not familiar to most economists, and that seems to conflict with the dominant approach to money. This chapter will focus primarily on what Goodhart identifies as the neglected “cartalist”, or “chartalist” approach to money, with a brief analysis of the historical evidence and only a passing reference to the critique of Mundel’s theory. I. The Orthodox, M-form, Approach Goodhart calls the orthodox approach the M-form, for Metalist. This is so dominant that it scarcely needs any exposition, however it will be useful to briefly outline its main features in order to contrast them with the “Chartalist” or C-form theory later. I still think the Metalist approach is best summarized in a quote from Samuelson I like to use. Inconvenient as barter obviously is, it represents a great step forward from a state of self-sufficiency in which every man had to be a jack-of-all-trades and master of none….If we were to construct history along hypothetical, logical lines, we should naturally follow the age of barter by the age of commodity money. -

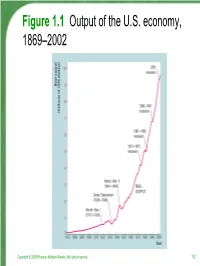

Figure 1.1 Output of the US Economy

Figure 1.1 Output of the U.S. economy, 1869–2002 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 1-2 Figure 1.2 Average labor productivity in the United States, 1900–2002 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 1-3 Figure 1.3 The U.S. unemployment rate, 1890–2002 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 1-4 Figure 1.4 Consumer prices in the United States Copyright © 2005 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 1-5 Figure 1.5 U.S. exports and imports, 1869– 2002 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 1-6 Figure 1.6 U.S. Federal government spending and tax collections, 1869–2002 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 1-7 THE BIG QUESTIONS • Thinking about the economy as a whole. General equilibrium. • What determines long-run economic growth? Can government policy help to change growth rates? “Half of the population of sub-Saharan Africa lives in absolute poverty. And, uniquely, Africa is getting poorer. Average income per head is lower now than it was 30 years ago.” Tony Blair, “A year of huge challenges”, The Economist, January 1, 2005. • Why does the unemployment rate fluctuate so much? What are the causes of business cy- cles? Can government policy help to stabilize the macroeconomy? Who benefits and who loses from such policy? • What causes inflation? Who benefits and who loses from inflation? Can central banks control inflation? • What are the effects of the current huge U.S. government budget deficits? Should Social Se- curity be reformed, and if so, how? Who bene- fits and who loses from reform? • What are the effects of the current large U.S. -

IS-LM: an Inquest

IS-LM: An Inquest William Darity Jr. and Warren Young Introduction Whether the IS-LM framework is to be vilified for its elusive, chameleon- like character or to be cherished for its flexibility remains an open question. What is not open to question is that its development and widespread adoption as the central mode of analytical expression for macroeconomists in the post-World War I1 era was linked intimately to the endeavor to give mathematical structure to Keynes’s General Theory (1936). In his book, Interpreting MKKeynes: The IS-LM Enigma (1987), one of the coauthors of this article, Warren Young, has examined the social and intellectual interactions among the principal figures involved in the creation of the IS-LM approach. The current essay has a different emphasis. Our focus here is on the tools rather than on the toolmakers. Therefore, we explore the content of the various models purporting to represent Keynes’s message below in comparative fashion, rather than the personalities who developed the models. There is surprising diversity in these early models. What places a macroeconomic model in the IS-LM tradition now seems to be its amenability to inclusion of equations that equate sav- Correspondence may be addressed to Professor William Darity, Department of Economics, CB ## 3305, Gardner Hall, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill NC 275 14 and Warren Young, Department of Economics, Bar-Ilan University, Israel. We are grateful to David Colander, Don Patinkin, and Thomas Rymes for valuable suggestions. Patinkin provided us with several valuable documents, including copies of Palander’s work. History of Political Economy 27: I @ 1995 by Duke University Press. -

PAUL A. SAMUELSON Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts Nobel Memorial Lecture, December 11, 1970

MAXIMUM PRINCIPLES IN ANALYTICAL ECONOMICS PAUL A. SAMUELSON Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts Nobel Memorial Lecture, December 11, 1970 The very name of my subject, economics, suggests economizing or maximizing. But Political Economy has gone a long way beyond home economics. Indeed, it is only in the last third of the century, within my own lifetime as a scholar, that economic theory has had many pretensions to being itself useful to the practical businessman or bureaucrat. I seem to recall that a great economist of the last generation, A. C. Pigou of Cambridge University, once asked the rhetorical question, “Who would ever think of employing an economist to run a brewery?” Well, today, under the guise of operational research and managerial economics, the fanciest of our economic tools are being utilized in enterprises both public and private. So at the very foundations of our subject maximization is involved. My old teacher, Joseph Schumpeter, went much farther. Instead of being content to say economics must borrow from logic and rational empirical enquiry, Schump- eter made the remarkable claim that man’s ability to operate as a logical animal capable of systematic empirical induction was itself the direct outcome of the Darwinian struggle for survival. Just as man’s thumb evolved in the struggle to make a living - to meet his economic problem - so did man’s brain evolve in response to the economic problem. Coming forty years before the latest findings in ethology by Konrad Lorenz and Nikolaas Tinbergen, this is a rather remarkable insight. It would take me away from my present subject to more than mention the further view enunciated by Schumpeter [1] in launching the new subject of econometrics. -

The Concentration of Unemployment Experience in Spells of Long Donation: an Analysis by Age and Sex Peter Brosnan T and John Hicks*

New Zealand journal of industrial relation..... 19X6. 11. 161-175 • The concentration of unemployment experience in spells of long donation: An analysis by age and sex Peter Brosnan t and John Hicks* ES'Iilnates of/he co1npleted duration of unen1plo.wnent are prepared by the generation life table n1ethod. lr ts found that the duration of unen1ployn1ent spells increases with age. llowever younger workers have a higher probability of beco1nin[!. unen1ployed. Thus their higher unetnployn1en1 rate is due to n1ore, but shorter spells of unen1ployn1ent. The dse 111 1he unenlploy1uent rate for n1ales in recent years is pritnari/y due to an increasing duration of unen1ploytnent. B'hen we decon1pose unetnploytnent by length ofspell. we find that spell'\ of 13 weeks and longer account for between 70 and 90 percent of all stgnijicant unen1ploytnent. These results call into quest ton the theoretical base of GO\'enunent's current en1ployn1ent polic.:v. Introduction In the late 1960s both Friedn1an (1968) and Phelp (1968) argued that there existed a ''natural" rate of unemployn1ent \vhich could not be reduced in the long run 'through an expansion of den1and without accelerating inflation. 'Further theoretical support for this proposition \\'as provided by the development of job search theory which auributed unernployJnent to rational, voluntary decisions on the part of the unemployed~ A familiar then1e to this literature is that the average durarion of con1pleted spells of une•nployment is quite short. In particular, conventional econo·mic wisdom holds that it is the youth group (15-25 y~ars) that \Viii n1ost clearly ~exhibit characteristics of this type (Trivedi and Baker, 1982). -

State Budgeting and Lessons Learned from the Economic Downturn

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF STATE BUDGET OFFICERS I SUMMER 2013 STATE BUDGETING AND LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE ECONOMIC DOWNTURN ANALYSIS AND COMMENTARY FROM STATE BUDGET OFFICERS This report is based on research funded by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. We thank them for their support and note that the findings and conclusions contained within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the MacArthur Foundation. THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF STATE BUDGET OFFICERS, founded in 1945, is the instrument through which the states collectively advance state budget practices. The major functions of the organization consist of research, policy development, education, training, and technical assistance. These are achieved primarily through NASBO’s publications, membership meetings, and training sessions. Association membership is composed of the heads of state finance departments, the states’ chief budget officers, and their deputies. All other state budget office staff are associate members. 2011–2012 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 2012–2013 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE John Hicks, Kentucky, President Jason Dilges, South Dakota, President Jason Dilges, South Dakota, President-Elect George Naughton, Oregon, President-Elect and Chair, Critical John Nixon, Michigan, Past President Issue Committee on Lessons Learned from the Downturn John Hicks, Linda Luebbering, Missouri, Member-at-Large Kentucky, Past President Linda Luebbering, David Treasure, Maryland, Member-at-Large Missouri, Member-at-Large Gerry Oligmueller, Thomas -

Introduction: Seven Decades of the IS-LM Model Michel De Vroey and Kevin D

Introduction: Seven Decades of the IS-LM Model Michel De Vroey and Kevin D. Hoover For some twenty-five years after the end of World War II, the IS-LM model dominated macroeconomics. With the advent of the new clas- sical macroeconomics in the early 1970s, that dominance was at first challenged and then broken. Yet the IS-LM model lives on. While no longer central to the graduate training of most macroeconomists or to cutting-edge macroeconomic research, the IS-LM model continues to be a mainstay of undergraduate textbooks, finds wide application in ar- eas of applied macroeconomics away from the front lines of macroeco- nomic theory, and lies at the conceptual core of most government and commercial macroeconometric models. What explains the rise, the fall, and the persistence of the IS-LM model? This volume presents essays from the HOPE conference held 25–27 April 2003 at Duke University that provide partial answers to this question. In addition to the ten essays from the conference, we are fortunate to be able to reprint an address delivered by Robert Lucas in conjunction with the conference. Profes- sor Lucas made his remarks at a reception celebrating the commitment of his professional papers to Duke University’s Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, where they will be housed with the pa- pers of other distinguished economists received through the Economists’ Papers Project. As Lucas is one of the central players in the intellectual movement that ultimately dethroned the IS-LM model, his lecture stands We thank the editors of HOPE—Craufurd Goodwin, Neil De Marchi, and E. -

Nber Working Paper Series Recent Developments A

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN MACROECONOMICS: A VERY QUICK REFRESHER COURSE N. Gregory Mankiw Working Paper No. 2474 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 December 1987 This paper was prepared for a conference at the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, October 30-31, 1987. The research reported here is part of the NBER's research program in Economic Fluctuations. Any opinions expressed are those of the author and not those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER Working Paper #2474 December 1987 Recent Developments in Macroeconomics: A Very Quick Refresher Course ABSTRACT This paper outlines the major developments in macroeconomics over the past two decades. It examines the reasons for the breakdown in the consensus view of the l960s and how this breakdown has guided research in macroeconomics. The introduction and importance of "rational expectations" are discussed, as are recent advances within the new classical and new Keynesian paradigms. N. Gregory Mankiw NBER 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 Fifteen or twenty years ago, it was much easier being a student of macroeconomics. Macroeconomists felt more sure of the answers they gave to questions such as, "What causes output and employment to fluctuate?" and "What is the correct policy response to these fluctuations?" At the textbook level, the accepted model of the economy was the Is-LM model. It was little changed from John Hicks's (1937) interpretation of John Maynard Keynes's (1936) once revolutionary vision of the macroeconomy. The IS-LM model takes prices as given. To explain the adjustment of prices, a Phillips curve of some sort was appended.