John Creedy Department of Economics Working Paper Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digitalisation and Monetary Policy

Does the liquidity trap exist? Lhuissier, Mojon and Rubio-Ramirez AEA Congress, 4 January 2021 The views expressed here are mine and should not be attributed to the BIS Restricted “A liquidity trap may be defined as a situation in which conventional monetary policies have become impotent, because nominal interest rates are at or near zero: injecting monetary base into the economy has no effect, because base and bonds are viewed by the private sector as perfect substitutes” Paul Krugman (1998) Restricted 2 Outline 1. Motivation 2. Literature 3. Empirical analysis 4. Results 5. Discussion Restricted 3 1. Motivation: How low can long-term rates be? Central bank balance sheets1 Share of government bonds held by central banks2 % of GDP % of GDP % Restricted 4 1. Motivation: Is there a lack of monetary policy space? • Cutting down short rates and purchasing assets to cut long rates can go only so far and • the lack of “interest rate” space is very critical in several advanced economies • However, into the medium we still need to assess whether and how much MP can do when short-term rates are near the ZLB/ELB Restricted 5 Literature: The ZLB makes MP ineffective Japan . Krugman (1998) – Coenen and Wieland (2003) “John Hicks, in introducing both the IS-LM model and the liquidity trap, identified the assumption that monetary policy is ineffective, rather than the assumed downward inflexibility of prices, as the central difference between Mr. Keynes and the classics.” US and EA, before the facts . Early Fed attemps: Furher and Madigan (97); Orphanides and Williams & Reifschneider and Williams (2000) . -

Edward S. Shaw* Simon Kuznets Remarked in His Capital in The

Edward S. Shaw* Simon Kuznets remarked in his Capital in rate. There is physical wealth, its ownership The American Economy, " ... extrapolation of represented by an homogeneous financial asset inflationary pressures over the next thirty in the form of common stock or "equity," and years raises a specter of intolerable conse there is wealth in the form of real money bal quences.... "1 Fifteen of the thirty years are ances. Accumulation of physical and monetary over, and inflation has accelerated. The central wealth derives from a constant rate of saving concern of this paper is whether Kuznets' pre for the community. Inflation occurs because the diction of "intolerable consequences" for capital growth rate of nominal money exceeds the markets and capital accumulation is on track or growth rate of real money demanded. patently wrong. 2 The inflation is immaculate because its pace Monetary theory distinguishes between "im is constant and perfectly foreseen and because maculate" inflation, "clean" inflation, and the inflation tax on real money balances is com "dirty" inflation. It is the last of these that pensated precisely by a deposit-rate of interest Kuznets dreaded and that we have endured. The on money. It is fully anticipated, and it does not first section below deals very briefly with dif impose a relative penalty on the money form of ferences between the three styles of inflation. wealth. Money-wage rates rise faster than out The second section is a catalogue of ways in put prices in the degree that labor productivity which dirty inflation may obstruct and distort is growing. -

The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER , President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 4, 2016, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters GARY BURTON WENDY OXENHORN PHAROAH SANDERS ARCHIE SHEPP Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center’s Artistic Director for Jazz. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 2 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, pianist and Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, chairman of the NEA DEBORAH F. RUTTER, president of the Kennedy Center THE 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS Performances by NEA JAZZ MASTERS: CHICK COREA, piano JIMMY HEATH, saxophone RANDY WESTON, piano SPECIAL GUESTS AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE, trumpeter LAKECIA BENJAMIN, saxophonist BILLY HARPER, saxophonist STEFON HARRIS, vibraphonist JUSTIN KAUFLIN, pianist RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA, saxophonist PEDRITO MARTINEZ, percussionist JASON MORAN, pianist DAVID MURRAY, saxophonist LINDA OH, bassist KARRIEM RIGGINS, drummer and DJ ROSWELL RUDD, trombonist CATHERINE RUSSELL, vocalist 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS -

Rese4b Instituti

RESE4B INSTITUTI The International Food Policy Research Institute was established in 1975 to identify and analyze alternative national and international strategies and policies for meeting food needs of the developing world on a sustainable basis, with particular emphasis on low- income countries and on the poorer groups in those countries. While the research effort is geared to the precise objective of contributing to the reduction of hunger and malnutrition, the factors involved are many and wide-ranging, requiring analysis of under lying processes and extending beyond a narrowly defined food sector. The Institute's research program reflects worldwide collaboration with governments and private and public institutions interested in in creasing food production and improving the equity of its distribution. Research results are disseminated to policymakers, opinion formers, administrators, policy analysts, researchers, and others concerned with na tional and international food and agricultural policy. IFPRI is a member of the Consultative Group on Inter national Agricultural Research and receives support from a number of governments, multilateral organiza tions, foundations, and other sources. INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE IFPRI REPORT 1993 CONTENTS Introduction: The Year in Review Per Pinstrup-Andersen Research Results 1 1 Environment and Production Technology Division 15 Markets and Structural Studies Division 19 Food Consumption and Nutrition Division 23 Trade and Macroeconomics Division Outreach 25 Outreach Division 29 Collaboration 33 Publications and Papers 43 Personnel 47 Financial Statements BOARD OF TRUSTEES Gerry Helleiner, Chairman James Charles Ingram Professor of Economics Director University of Toronto The Australian Institute of Toronto, Canada International Affairs Canberra, Australia Sjarifuddin Baharsjah Junior Minister Dharma Kumar Ministry of Agriculture Professor of Economic History Jakarta, Indonesia Delhi School of Economics New Delhi, India David E. -

10-25-13 Jazz Ensemble

Williams College Department of Music Williams Jazz Ensemble Kris Allen, Director Introduction: Smile Please - Stevie Wonder, arranged by Kris Allen Young up- and -coming composers and arrangers of the New York scene: After the Morning - John Hicks, arranged by David Gibson Arabia - Curtis Fuller, arranged by Chris Casey Noctilucent Shift - Sara Jacovino Small Combo: Passion Dance - McCoy Tyner Jonathan Dely '15, trumpet; Taylor Halperin '14, piano; Greg Ferland '16, bass; Brian Levine '16, drums Coached by Avery Sharpe My Funny Valentine - Richard Rogers and Lorenz Hart, arranged by Max Seigel SKJ Blues - Milt Jackson, arranged by James Burton Going Somewhere - James Burton Saxophones Trumpets Rhythm Nikki Caravelli '16 Richard Whitney '16 Nathaniel Vilas '17 - piano Max Dietrick '16 Jonathan Dely '15 Austin Paul '16 - vibraphone Jackson Myers '17 Will Hayes '14 Jack Schweighauser '15 - guitar Samantha Polsky '17 Byron Perpetua '14 Greg Ferland '16 - bass Sammi Jo Stone '17 Paul Heggeseth Brian Levine '16 - drumset Trombones Hartley Greenwald '16 Jeff Sload '17 Allen Davis '14 Nico Ekasumara '14 Friday, October 25, 2013 8:00 p.m. Chapin Hall Williamstown, Massachusetts Please turn off cell phones. No photography or recording is permitted. Upcoming Events: See music.williams.edu for full details and additional happenings as well as to sign up for the weekly e-newsletters. 10/27 3:00pm Visiting Artists Freddie Bryant & Shubhendra Rao Brooks-Rogers Recital Hall 10/29 4:15pm Master Class with Visiting Artist Jonathan Biss, piano Chapin Hall -

CR Traverse Analysis Progenitors & Pioneers

Traverse Analysis: Progenitors and Pioneers 14th History of Economic Thought Society of Australia Conference The University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia. 11th July 2001 Colin Richardson* School of Economics University of Tasmania ABSTRACT Traverse analysis has two progenitors (David Ricardo, Karl Marx) and five pioneers: Michal Kalecki, Adolph Lowe, Joan Robinson, J.R. Hicks, and John Hicks. Defined as the dynamic disequilibrium adjustment-path that connects an initial with a different terminal state of economic growth, the traverse comes in four “flavours”. There are neoclassical (J.R. Hicks), neo-Austrian (John Hicks), observed (Ricardo, Marx, Kalecki, Robinson), and instrumental (Lowe) traverses. These terms are explained and the seven seminal contributions are summarised and commented upon in this paper. * I am indebted to Dr Jerry Courvisanos for his supervision and comments in writing this paper. Scholarship support from The University of Tasmania is also gratefully acknowledged. 2 Introduction Nobel laureate economist Robert Solow once quipped: “The traverse is the easiest part of skiing but the most difficult part of economics”. Later, Joseph Halevi and Peter Kriesler (1992, p 225) complained that “The traverse is at the same time one of the most important concepts in economic theory, and also one of the most neglected.” This paper outlines briefly the history of economic thought between 1821 and 1973 concerning this difficult, important and neglected theoretical construct. Traverse analysis has two progenitors (David Ricardo, Karl Marx) and five pioneers: Michal Kalecki, Adolph Lowe, Joan Robinson, J.R. Hicks, and John Hicks. Defined as the dynamic disequilibrium adjustment-path that connects an initial with a different terminal state of economic growth, the traverse comes in four “flavours”. -

Unemployment Did Not Rise During the Great Depression—Rather, People Took Long Vacations

Working Paper No. 652 The Dismal State of Macroeconomics and the Opportunity for a New Beginning by L. Randall Wray Levy Economics Institute of Bard College March 2011 The Levy Economics Institute Working Paper Collection presents research in progress by Levy Institute scholars and conference participants. The purpose of the series is to disseminate ideas to and elicit comments from academics and professionals. Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, founded in 1986, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, independently funded research organization devoted to public service. Through scholarship and economic research it generates viable, effective public policy responses to important economic problems that profoundly affect the quality of life in the United States and abroad. Levy Economics Institute P.O. Box 5000 Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 12504-5000 http://www.levyinstitute.org Copyright © Levy Economics Institute 2011 All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Queen of England famously asked her economic advisers why none of them had seen “it” (the global financial crisis) coming. Obviously, the answer is complex, but it must include reference to the evolution of macroeconomic theory over the postwar period— from the “Age of Keynes,” through the Friedmanian era and the return of Neoclassical economics in a particularly extreme form, and, finally, on to the New Monetary Consensus, with a new version of fine-tuning. The story cannot leave out the parallel developments in finance theory—with its efficient markets hypothesis—and in approaches to regulation and supervision of financial institutions. This paper critically examines these developments and returns to the earlier Keynesian tradition to see what was left out of postwar macro. -

The Neo-Chartalist Approach to Money by L. Randall Wray

The Neo-Chartalist Approach to Money by L. Randall Wray* Working Paper No. 10 July 2000 ∗ Senior Research Associate, Center for Full Employment and Price Stability, University of Missouri-Kansas City In his interesting and important chapter, Charles Goodhart makes three main contributions. First, he argues that there are two competing approaches to the study of money, with one dominating most research and policy formation to the virtual exclusion of the other. Second, he examines and rejects Mundel’s Optimal Currency Area approach, which is based on the dominant approach to money, leading to a criticism of the theoretical basis for European Monetary Union. Finally, he introduces some historical literature on the origins of coins and money that is not familiar to most economists, and that seems to conflict with the dominant approach to money. This chapter will focus primarily on what Goodhart identifies as the neglected “cartalist”, or “chartalist” approach to money, with a brief analysis of the historical evidence and only a passing reference to the critique of Mundel’s theory. I. The Orthodox, M-form, Approach Goodhart calls the orthodox approach the M-form, for Metalist. This is so dominant that it scarcely needs any exposition, however it will be useful to briefly outline its main features in order to contrast them with the “Chartalist” or C-form theory later. I still think the Metalist approach is best summarized in a quote from Samuelson I like to use. Inconvenient as barter obviously is, it represents a great step forward from a state of self-sufficiency in which every man had to be a jack-of-all-trades and master of none….If we were to construct history along hypothetical, logical lines, we should naturally follow the age of barter by the age of commodity money. -

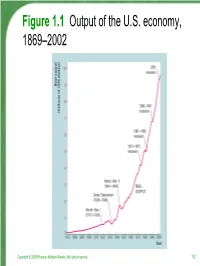

Figure 1.1 Output of the US Economy

Figure 1.1 Output of the U.S. economy, 1869–2002 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 1-2 Figure 1.2 Average labor productivity in the United States, 1900–2002 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 1-3 Figure 1.3 The U.S. unemployment rate, 1890–2002 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 1-4 Figure 1.4 Consumer prices in the United States Copyright © 2005 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 1-5 Figure 1.5 U.S. exports and imports, 1869– 2002 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 1-6 Figure 1.6 U.S. Federal government spending and tax collections, 1869–2002 Copyright © 2005 Pearson Addison-Wesley. All rights reserved. 1-7 THE BIG QUESTIONS • Thinking about the economy as a whole. General equilibrium. • What determines long-run economic growth? Can government policy help to change growth rates? “Half of the population of sub-Saharan Africa lives in absolute poverty. And, uniquely, Africa is getting poorer. Average income per head is lower now than it was 30 years ago.” Tony Blair, “A year of huge challenges”, The Economist, January 1, 2005. • Why does the unemployment rate fluctuate so much? What are the causes of business cy- cles? Can government policy help to stabilize the macroeconomy? Who benefits and who loses from such policy? • What causes inflation? Who benefits and who loses from inflation? Can central banks control inflation? • What are the effects of the current huge U.S. government budget deficits? Should Social Se- curity be reformed, and if so, how? Who bene- fits and who loses from reform? • What are the effects of the current large U.S. -

Sylvia Cuenca Long

SYLVIA CUENCA Sylvia is an active drummer on the New York jazz scene who is contributing outstanding performances in a variety of situations. She has had the honor of sharing the bandstand with saxophone legend Joe Henderson for 4 years and trumpet legend Clark Terry for 17 years. The Joe Henderson quartet toured frequently in European countries Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Austria, Belgium, England, Switzerland, France, Italy and Germany and venues across the U.S. In a trio setting she performed with Joe Henderson and Charlie Haden in 1989 and with George Mraz in 1994. She performed with the Clark Terry Quintet and Big Band at Village Vanguard, Birdland, Blue Note, Queen Elizabeth 2, Royal Viking, S.S. Norway jazz cruises and clubs, concerts and festivals in the U.S, Europe, the Caribbean and South America. While working with the Clark Terry quintet she had the opportunity to perform with guest artists Al Grey, Red Holloway, Jimmy Heath, Frank Wess, Marian McPartland, Dianne Reeves, Joe Williams and Lou Donaldson to name a few. Cuenca has also performed with such jazz luminaries as Billy Taylor, Frank Foster’s Loud Minority Big Band, Houston Person, Etta Jones, Helen Merrill, John Hicks, Valery Ponomarov, Lew Soloff, James Spaulding, Kenny Barron, Ray Drummond, Michael Brecker, Randy Brecker, George Cables, Hilton Ruiz, Jon Faddis, Eddie Henderson, Gary Bartz, Kenny Drew Jr., Emily Remler, Richie Cole, Dave Stryker, Jessie Davis, Ralph Bowen, Vincent Herring, Paul Bollenback, Geoffrey Keezer, Mark Whitfield, Ralph Moore, Catherine Russell, Dianne Reeves, Dianne Schuur, the European based Vienna Art Orchestra and many others. -

THE POETRY of JOHN V. HICKS a Thesis Submitted to The

“AWASH PERILOUSLY WITH SONG”: THE POETRY OF JOHN V. HICKS A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts In the Department of English University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Paula Jane Remlinger Keywords: John V. Hicks, poetry, music, Canadian, Saskatchewan © Copyright Paula Jane Remlinger, September, 2006. All rights reserved. Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of English University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan (S7N 5A5) ABSTRACT This thesis is the first scholarly study on the work of Saskatchewan poet John V. -

Monterey Jazz Festival

DECEMBER 2018 VOLUME 85 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael Weintrob;