UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

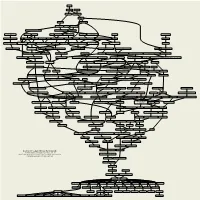

Academic Genealogy of George Em Karniadakis

Nilos Kabasilas Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università di Padova 1462 Università di Firenze Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano Università di Mantova 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova 1477 Università di Firenze Leo Outers Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas à Kempis Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Pelope Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia François Dubois Jean Tagault Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain Università di Padova Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe / Collège de Montaigu 1474 1406 Universität Wien Niccolò Leoniceno Jacobus (Jacques Masson) Latomus Desiderius Erasmus Petrus (Pieter de Corte) Curtius Pietro Pomponazzi Jacobus (Jacques -

H-Diplo JOURNAL WATCH, a to I H-Diplo Journal and Periodical Review Third Quarter 2015 20 July 2015

[jw] H-Diplo JOURNAL WATCH, A to I H-Diplo Journal and Periodical Review Third Quarter 2015 20 July 2015 Compiled by Erin Black, University of Toronto African Affairs, Vol.114, No. 456 (July 2015) http://afraf.oxfordjournals.org/content/vol114/issue456/ . “Rejecting Rights: Vigilantism and violence in post-apartheid South Africa,” by Nicholas Rush Smith, 341- . “Ethnicity, intra-elite differentiation and political stability in Kenya,” by Biniam E. Bedasso, 361- . “The political economy of grand corruption in Tanzania,” by Hazel S. Gray, 382- . The political economy of property tax in Africa: Explaining reform outcomes in Sierra Leone,” by Samuel S. Jibao and Wilson Prichard, 404- . “After restitution: Community, litigation and governance in South African land reform,” by Christiaan Beyers and Derick Fay, 432- Briefing . “Why Goodluck Jonathan lost the Nigerian presidential election of 2015,” by Olly Owen and Zainab Usmanm 455- African Historical Review, Vol. 46, No.2 (December 2014) http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rahr20/46/2 . “The Independence of Rhodesia in Salazar's Strategy for Southern Africa,” by Luís Fernando Machado Barroso, 1- This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- nd/3.0/us/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. H-Diplo Journal Watch [jw], A-I, Third Quarter 2015 . “‘The Rebellion From Below’ and the Origins of Early Zionist Christianity,” by Barry Morton, 25- . “The Stag of the Eastern Cape: Power, Status and Kudu Hunting in the Albany and Fort Beaufort Districts, 1890 to 1905,” by David Gess & Sandra Swart, 48- . -

A Study in the Berlin Haskalah 1975

ISAAC SA TANOW, THE MAN AND HIS WORK; A STUDY IN THE BERLIN HASKALAH By Nehama Rezler Bersohn Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Philosophy Columbia University 1975 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am very grateful to Professor I. Barzilay for his friendly advice and encouragement throughout the course of my studies and research. Thanks are also due to the Jewish Memorial Foundation for a grant. i Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ABSTRACT ISAAC SATANOW, THE MAN AND HIS WORK; A STUDY IN THE BERLIN HASKAIAH Nehama Rezler Bersohn Isaac Satanow, one of the most prolific writers of the Berlin Haskalah (Jewish enlightenment), typifies the maskil (an enlightened Jew) of his time. He was born and reared in Podolia, Poland at a time when Frankism and Cabbalah were reaching their peak influence. He subsequently moved to Berlin where the Jewish enlightenment movement was gaining momentum influenced by the general enlightenment and Prussia's changing economy. Satanow's way of life expressed the con fluence of these two worlds, Podolia and Berlin. Satanow adopted the goal of the moderate Haskalah to educate the Jewish masses, and by teaching them modern science, modern languages and contemporary ideas, to help them in improving their economic, social and political situation. To achieve this goal, he wrote numerous books and articles, sometimes imitating styles of and attributing the authorship to medieval and earlier writers so that his teaching would be respected and accepted. -

The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Edinburgh Research Explorer Edinburgh Research Explorer The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School Citation for published version: Cairns, JW 2007, 'The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School: The Union of 1707 and the Regius Chair' Edinburgh Law Review, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 300-48. DOI: 10.3366/elr.2007.11.3.300 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.3366/elr.2007.11.3.300 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Edinburgh Law Review Publisher Rights Statement: ©Cairns, J. (2007). The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School: The Union of 1707 and the Regius Chair. Edinburgh Law Review, 11, 300-48doi: 10.3366/elr.2007.11.3.300 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Apr. 2019 EdinLR Vol 11 pp 300-348 The Origins of the Edinburgh Law School: the Union of 1707 and the Regius Chair John W Cairns* A. -

Helmut Walser Smith, "Nation and Nationalism"

Smith, H. Nation and Nationalism pp. 230-255 Jonathan Sperber., (2004) Germany, 1800-1870, Oxford: Oxford University Press Staff and students of University of Warwick are reminded that copyright subsists in this extract and the work from which it was taken. This Digital Copy has been made under the terms of a CLA licence which allows you to: • access and download a copy; • print out a copy; Please note that this material is for use ONLY by students registered on the course of study as stated in the section below. All other staff and students are only entitled to browse the material and should not download and/or print out a copy. This Digital Copy and any digital or printed copy supplied to or made by you under the terms of this Licence are for use in connection with this Course of Study. You may retain such copies after the end of the course, but strictly for your own personal use. All copies (including electronic copies) shall include this Copyright Notice and shall be destroyed and/or deleted if and when required by University of Warwick. Except as provided for by copyright law, no further copying, storage or distribution (including by e-mail) is permitted without the consent of the copyright holder. The author (which term includes artists and other visual creators) has moral rights in the work and neither staff nor students may cause, or permit, the distortion, mutilation or other modification of the work, or any other derogatory treatment of it, which would be prejudicial to the honour or reputation of the author. -

Jegór Von Sivers' Herderian Cosmopolitanism

Ajalooline Ajakiri, 2012, 1/2 (139/140), 79–113 Humanität versus nationalism as the moral foundation of the Russian Empire: Jegór von Sivers’ Herderian cosmopolitanism* Eva Piirimäe No single author is more important for the development of nationalism in Central and Eastern Europe than Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803).1 Yet Herder’s own relationship to nationalism continues to be debated.2 This is partly owed to the ambivalence of the notion “nationalism” itself. There is no doubt Herder is a “nationalist”, if by this term we refer to someone who defends national diversity as valuable and cherishes and cultivates one’s own language and national customs. Yet, it is more common in the anglo- phone world to use the term “nationalist” for someone who supports one’s nation’s aggressive foreign policies. In this case, Herder is rather an oppo- nent of nationalism. There is also a third widely used notion of national- ism, known also as the “principle of nationality” according to which “the * Research for this article has been funded by the Estonian Science Foundation Grant No. 8887 and the Target Financed Program No. SF0180128s08. 1 See Peter Drews, Herder und die Slaven: Materialien zur Wirkungsgeschichte bis zur Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts (München: Sagner, 1990); Johann Gottfried Herder: zur Herder-Rezeption in Ost- und Südosteuropa, ed. by Gerhard Ziegengeist (Berlin-Ost: Akademie-Verlag, 1978); Holm Sundhaussen, Der Einfluß der Herderschen Ideen auf die Nationsbildung bei den Völkern der Habsburger Monarchie (München: Oldenburg, 1973); Konrad Bittner, “Herders ‘Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit’ und ihre Auswirkung bei den slavischen Hauptstämmen”, Germanoslavica, 2 (1932/33), 453–480; Konrad Bittner, Herders Geschichtsphilosophie und die Slawen (Reichenberg: Gebrüder Stiepel, 1929). -

The British Journal for the History of Science Mechanical Experiments As Moral Exercise in the Education of George

The British Journal for the History of Science http://journals.cambridge.org/BJH Additional services for The British Journal for the History of Science: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Mechanical experiments as moral exercise in the education of George III FLORENCE GRANT The British Journal for the History of Science / Volume 48 / Issue 02 / June 2015, pp 195 - 212 DOI: 10.1017/S0007087414000582, Published online: 01 August 2014 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0007087414000582 How to cite this article: FLORENCE GRANT (2015). Mechanical experiments as moral exercise in the education of George III. The British Journal for the History of Science, 48, pp 195-212 doi:10.1017/ S0007087414000582 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BJH, IP address: 130.132.173.207 on 07 Jul 2015 BJHS 48(2): 195–212, June 2015. © British Society for the History of Science 2014 doi:10.1017/S0007087414000582 First published online 1 August 2014 Mechanical experiments as moral exercise in the education of George III FLORENCE GRANT* Abstract. In 1761, George III commissioned a large group of philosophical instruments from the London instrument-maker George Adams. The purchase sprang from a complex plan of moral education devised for Prince George in the late 1750s by the third Earl of Bute. Bute’s plan applied the philosophy of Frances Hutcheson, who placed ‘the culture of the heart’ at the foundation of moral education. To complement this affective development, Bute also acted on seventeenth-century arguments for the value of experimental philosophy and geometry as exercises that habituated the student to recognizing truth, and to pursuing it through long and difficult chains of reasoning. -

251 Chapter IX Revolution And

251 Chapter IX Revolution and Law (1789 – 1856) The Collapse of the European States System The French Revolution of 1789 did not initialise the process leading to the collapse of the European states system but accelerated it. In the course of the revolution, demands became articulate that the ruled were not to be classed as subjects to rulers but ought to be recognised as citizens of states and members of nations and that, more fundamentally, the continuity of states was not a value in its own right but ought to be measured in terms of their usefulness for the making and the welfare of nations. The transformations of groups of subjects into nations of citizens took off in the political theory of the 1760s. Whereas Justus Lipsius and Thomas Hobbes1 had described the “state of nature” as a condition of human existence that might occur close to or even within their present time, during the later eighteenth century, theorists of politics and international relations started to position that condition further back in the past, thereby assuming that a long period of time had elapsed between the end of the “state of nature” and the making of states and societies, at least in some parts of the world. Moreover, these theorists regularly fused the theory of the hypothetical contract for the establishment of government, which had been assumed since the fourteenth century, with the theory of the social contract, which had only rarely been postulated before.2 In the view of later eighteenth-century theorists, the combination of both types of contract was to establish the nation as a society of citizens.3 Supporters of this novel theory of the combined government and social contract not merely considered human beings as capable of moving out from the “state of nature” into states, but also gave to humans the discretional mandate to first form their own nations as what came to be termed “civil societies”, before states could come into existence.4 Within states perceived in accordance with these theoretical suppositions, nationals remained bearers of sovereignty. -

Genealogical History of the House of Wishart

MEMOIR OF GEORGE WISHART. 329 GENEALOGICAL HISTORY OF THE HOUSE OF WISHART. NlSBET's statement as to the family of Wishart having derived descent from Robert, an illegitimate son of David, Earl of Huntingdon, who was styled Guishart on account of his heavy slaughter of the Saracens, is an evident fiction.* The name Guiscard, or Wiscard, a Norman epithet used to designate an adroit or cunning person, was conferred on Robert Guiscard, son of Tancrede de Hauterville of Nor- mandy, afterwards Duke of Calabria, who founded the king- dom of Sicily. This noted warrior died on the 27th July 1085. His surname was adopted by a branch of his House, and the name became common in Normandy and throughout France. Guiscard was the surname of the Norman kings of Apulia in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. John Wychard is mentioned as a small landowner in the Hundred de la Mewe, Buckinghamshire, in the reign of Henry III. (I2i6-i272)/1- During the same reign and that of Edward I. (1272-1307), are named as landowners, Baldwin Wyschard or Wistchart, in Shropshire; Nicholas Wychard, in Warwickshire ; Hugh Wischard, in Essex; and William Wischard, in Bucks.j In the reign of Edward I. Julian Wye- chard is named as occupier of a house in the county of Oxford.§ A branch of the House of Wischard obtained lands in Scotland some time prior to the thirteenth century. John Wischard was sheriff of Kincardineshire in the reign of Alexander II. (1214-1249). In an undated charter of this monarch, Walter of Lundyn, and Christian his wife, grant to the monks of Arbroath a chalder of grain, " pro sua frater- nitate," the witnesses being John Wischard, " vicecomes de • Nisbet's System of Heraldry, Edin., 1816, folio, vol. -

Foundations of Psychology by Herman Bavinck

Foundations of Psychology Herman Bavinck Translated by Jack Vanden Born, Nelson D. Kloosterman, and John Bolt Edited by John Bolt Author’s Preface to the Second Edition1 It is now many years since the Foundations of Psychology appeared and it is long out of print.2 I had intended to issue a second, enlarged edition but the pressures of other work prevented it. It would be too bad if this little book disappeared from the psychological literature. The foundations described in the book have had my lifelong acceptance and they remain powerful principles deserving use and expression alongside empirical psy- chology. Herman Bavinck, 1921 1 Ed. note: This text was dictated by Bavinck “on his sickbed” to Valentijn Hepp, and is the opening paragraph of Hepp’s own foreword to the second, revised edition of Beginselen der Psychologie [Foundations of Psychology] (Kampen: Kok, 1923), 5. The first edition contains no preface. 2 Ed. note: The first edition was published by Kok (Kampen) in 1897. Contents Editor’s Preface �����������������������������������������������������������������������ix Translator’s Introduction: Bavinck’s Motives �������������������������� xv § 1� The Definition of Psychology ���������������������������������������������1 § 2� The Method of Psychology �������������������������������������������������5 § 3� The History of Psychology �����������������������������������������������19 Greek Psychology .................................................................19 Historic Christian Psychology ..............................................22 -

Directory for the City of Aberdeen

ABERDEEN CITY LIBRARIES Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/directoryforcity185556uns mxUij €i% of ^krtimt \ 1855-56. TO WHICH tS AI)DEI< [THE NAMES OF THE PRINCIPAL INHABITAxnTs OLD ABERDEEN AND WOODSIDE. %httim : WILLIAM BENNETT, PRINTER, 42, Castle Street. 185 : <t A 2 8S. CONTENTS. PAGE. Kalendar for 1855-56 . 5 Agents.for Insurance Companies . 6 Section I.-- Municipal Institutions 9 Establishments 12 ,, II. — Commercial ,, III. — Revenue Department 24 . 42 ,, IV.—Legal Department Department ,, V.—Ecclesiastical 47 „ VI. — Educational Department . 49 „ VII.— Miscellaneous Registration of Births, Death?, and Marri 51 Billeting of Soldiers .... 51: The Northern Club .... Aberdeenshire Horticultural Society . Police Officers, &c Conveyances from Aberdeen Stamp Duties Aberdeen Shipping General Directory of the Inhabitants of the City of Aberd 1 Streets, Squares, Lanes, Courts, &c 124 Trades, Professions, &c 1.97 Cottages, Mansions, and Places in the Suburbs Append ix i Old Aberdeen x Woodside BANK HOLIDAYS. Prince Albert's Birthday, . Aug. 26 New Year's Day, Jan 1 | Friday, Prince of Birthday, Nov. 9 Good April 6 | Wales' Queen's Birthday, . Christmas Day, . Dec. 25 May 24 | Queen's Coronation, June 28 And the Sacramental Fasts. When a Holiday falls on a Sunday, the Monday following is leapt, AGENTS FOR INSURANCE COMPANIES. OFFICES. AGENTS Aberd. Mutual Assurance & Fiieudly Society Alexander Yeats, 47 Schoolhill Do Marine Insurance Association R. Connon, 58 Marischal Street Accidental Death Insurance Co.~~.~~., , A Masson, 4 Queen Street Insurance Age Co,^.^,^.^.—.^,.M, . Alex. Hunter, 61 St. Nicholas Street Agriculturist Cattle Insurance Co.-~,.,„..,,„ . A. -

Academic Genealogy of Tom Hendrik Koornwinder Simon Speijert Van Der Eyk Universiteit Leiden the Mathematics Genealogy Project Is a Service Of

Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī Kamal al Din Ibn Yunus Nasir al-Din al-Tusi Shams ad-Din Al-Bukhari Maragheh Observatory Gregory Chioniadis 1296 Ilkhans Court at Tabriz Manuel Bryennios Theodore Metochites 1315 Gregory Palamas Nilos Kabasilas 1363 Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università degli Studi di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università degli Studi di Padova 1462 Università degli Studi di Firenze Theodoros Gazes Paolo (Nicoletti) da Venezia Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Angelo Poliziano Geert Gerardus Magnus Groote Florens Florentius Radwyn Radewyns Nicole Oresme 1433 Università di Mantova Università di Mantova 1477 Università degli Studi di Firenze 1433 Constantinople Demetrios Chalcocondyles Heinrich von Langenstein Gaetano da Thiene Sigismondo Polcastro Leo Outers Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas von Kempen à Kempis 1452 Accademia Romana 1363 Université de Paris 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università degli Studi di Firenze 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1452 Mystras 1375 Université de Paris Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Georgius Hermonymus Janus Lascaris Nicoletto Vernia Pietro Roccabonella Pelope Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Jean Tagault François Dubois Matthaeus Adrianus Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden