Luther's Lost Books and the Myth of the Memory Cult

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

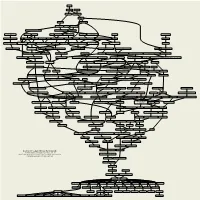

Academic Genealogy of George Em Karniadakis

Nilos Kabasilas Demetrios Kydones Elissaeus Judaeus Manuel Chrysoloras Georgios Plethon Gemistos 1380, 1393 Basilios Bessarion 1436 Mystras Guarino da Verona Johannes Argyropoulos 1408 1444 Università di Padova Vittorino da Feltre Cristoforo Landino Marsilio Ficino 1416 Università di Padova 1462 Università di Firenze Ognibene (Omnibonus Leonicenus) Bonisoli da Lonigo Theodoros Gazes Angelo Poliziano Università di Mantova 1433 Constantinople / Università di Mantova 1477 Università di Firenze Leo Outers Alessandro Sermoneta Gaetano da Thiene Moses Perez Scipione Fortiguerra Demetrios Chalcocondyles Jacob ben Jehiel Loans Rudolf Agricola Thomas à Kempis Heinrich von Langenstein 1485 Université Catholique de Louvain 1493 Università di Firenze 1452 Mystras / Accademia Romana 1478 Università degli Studi di Ferrara 1363, 1375 Université de Paris Maarten (Martinus Dorpius) van Dorp Pelope Pietro Roccabonella Nicoletto Vernia François Dubois Jean Tagault Girolamo (Hieronymus Aleander) Aleandro Janus Lascaris Matthaeus Adrianus Johann (Johannes Kapnion) Reuchlin Jan Standonck Alexander Hegius Johannes von Gmunden 1504, 1515 Université Catholique de Louvain Università di Padova Università di Padova 1516 Université de Paris 1499, 1508 Università di Padova 1472 Università di Padova 1477, 1481 Universität Basel / Université de Poitiers 1474, 1490 Collège Sainte-Barbe / Collège de Montaigu 1474 1406 Universität Wien Niccolò Leoniceno Jacobus (Jacques Masson) Latomus Desiderius Erasmus Petrus (Pieter de Corte) Curtius Pietro Pomponazzi Jacobus (Jacques -

Now Let Us Come Before Him Nun Laßt Uns Gehn Und Treten 8.8

Now Let Us Come Before Him Nun laßt uns gehn und treten 8.8. 8.8. Nun lasst uns Gott, dem Herren Paul Gerhardt, 1653 Nikolaus Selnecker, 1587 4 As mothers watch are keeping 9 To all who bow before Thee Tr. John Kelly, 1867, alt. Arr. Johann Crüger, alt. O’er children who are sleeping, And for Thy grace implore Thee, Their fear and grief assuaging, Oh, grant Thy benediction When angry storms are raging, And patience in affliction. 5 So God His own is shielding 10 With richest blessings crown us, And help to them is yielding. In all our ways, Lord, own us; When need and woe distress them, Give grace, who grace bestowest His loving arms caress them. To all, e’en to the lowest. 6 O Thou who dost not slumber, 11 Be Thou a Helper speedy Remove what would encumber To all the poor and needy, Our work, which prospers never To all forlorn a Father; Unless Thou bless it ever. Thine erring children gather. 7 Our song to Thee ascendeth, 12 Be with the sick and ailing, Whose mercy never endeth; Their Comforter unfailing; Our thanks to Thee we render, Dispelling grief and sadness, Who art our strong Defender. Oh, give them joy and gladness! 8 O God of mercy, hear us; 13 Above all else, Lord, send us Our Father, be Thou near us; Thy Spirit to attend us, Mid crosses and in sadness Within our hearts abiding, Be Thou our Fount of gladness. To heav’n our footsteps guiding. 14 All this Thy hand bestoweth, Thou Life, whence our life floweth. -

Philip Melanchthon and the Historical Luther by Ralph Keen 7 2 Philip Melanchthon’S History of the Life and Acts of Dr Martin Luther Translated by Thomas D

VANDIVER.cvr 29/9/03 11:44 am Page 1 HIS VOLUME brings By placing accurate new translations of these two ‘lives of Luther’ side by side, Vandiver together two important Luther’s T and her colleagues have allowed two very contemporary accounts of different perceptions of the significance of via free access the life of Martin Luther in a Luther to compete head to head. The result is as entertaining as it is informative, and a Luther’s confrontation that had been postponed for more than four powerful reminder of the need to ensure that secondary works about the Reformation are hundred and fifty years. The first never displaced by the primary sources. of these accounts was written imes iterary upplement after Luther’s death, when it was rumoured that demons had seized lives the Reformer on his deathbed and dragged him off to Hell. In response to these rumours, Luther’s friend and colleague, Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/25/2021 06:33:04PM Philip Melanchthon wrote and Elizabeth Vandiver, Ralph Keen, and Thomas D. Frazel - 9781526120649 published a brief encomium of the Reformer in . A completely new translation of this text appears in this book. It was in response to Melanchthon’s work that Johannes Cochlaeus completed and published his own monumental life of Luther in , which is translated and made available in English for the first time in this volume. After witnessing Luther’s declaration before Charles V at the Diet of Worms, Cochlaeus had sought out Luther and debated with him. However, the confrontation left him convinced that Luther was an impious and —Bust of Luther, Lutherhaus, Wittenberg. -

Bishop's Newsletter

Bishop’s Newsletter June 2016 North/ In this Issue: West Lower Michigan Synod 500 Years of Reformation Youth and Faith Formation 2900 N. Waverly Rd. Tables Lansing, MI 48906 Upcoming Events 517-321-5066 Congregations in Transition 500 Years of Reformation — 500 Trees for Wittenberg "Even if I knew that the world were to collapse Trees are planted in the Luthergarten by the Castle tomorrow, I would still plant my apple tree Church, along the drive, and by the new town hall. today" (ascribed to Martin Luther). The main garden is fashioned in the shape of the Luther Rose. The center trees, or the foundational As the opening paragraph trees of the garden were planted by The Roman on the Luthergarten Catholic Church – Pontifical Council Promoting webpage Christian Unity; The Orthodox Church; The (www.luthergarten.de) Anglican Communion; World Alliance of Reformed explains: Churches; World Methodist Council; and The Lutheran World Federation. In 2017, Lutheran churches will commemorate the On May 31, as part of a sabbatical trip to Germany, I 500th anniversary of the was privileged to “officially” plan our synod tree. As Reformation (Jubilee) that the sign indicates, our tree is # 282 and is located had its beginnings in along Hallesche Strasse, the southern boundary of Lutherstadt Wittenberg, the garden. Our Germany. As a means of giving expression to synod verse is commemoration, the Luthergarten has been John 12:32 "And I, established in Wittenberg on the grounds of the when I am lifted former town fortifications. In connection with this up from the earth, project, 500 trees will be planted at different places will draw all in the city region, giving a concrete sign of the people to myself." optimism so clearly expressed in Luther's apple tree quote. -

Xerox University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Prince of Peace News Volume LVII, Issue Ix OCTOBER 2018 Anno Domini for the Teachings of the Reformation

Prince of Peace News Volume LVII, Issue ix OCTOBER 2018 Anno Domini for the teachings of the reformation. We 3496 E. Morgan Street The Luther Rose focus our faith on Jesus and how He saved Martinsville, IN by Grace Alone, that we embrace by Faith Dear friends in Christ, Alone, as taught in Scripture Alone. The Church: 765-342-2004 As we enter the month of October, I am teachings of the Bible continue to be the School: 765-349-8873 once again reminded of the rich history that focus of our education at Prince of Peace. Daycare: 765-342-2220 has established the Lutheran Church. One of As we reflect on the Reformation, we also Fax: 765-813-0036 the symbols of the Lutheran Church is the remember the documents contained in the Luther Rose that Dr. Martin Luther put before Book of Concord: The Augsburg Confession, the people to teach the truths of Scripture in a 1530; the Apology of the Augsburg Confes- Meet our staff: visual way. sion, 1531; The Smalcald Articles, 1537; The Pastor: Rev. Nathan Janssen Here is how Martin Luther explained it: Power and Primacy of the Pope, 1537; The Vicar: Christian Schultz First, there is a black cross in a heart that Small Catechism, 1529; the Large remains its natural color. This is to remind Catechism, 1529; The Formula of Concord, Secretaries: Sharon Raney & Beth Wallis me that it is faith in the Crucified One that Epitome, 1577; and The Formula of Concord, Director of Youth Ministries: Sharon Raney saves us. Anyone who believes from the Solid Declaration, 1577. -

Confessio Im Konflikt Religiöse Selbst- Und Fremdwahrnehmung in Der Frühen Neuzeit

Mona Garloff / Christian Volkmar Witt (Hg.) Confessio im Konflikt Religiöse Selbst- und Fremdwahrnehmung in der Frühen Neuzeit. Ein Studienbuch © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666571428 | CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Europäische Geschichte Mainz Abteilung für Abendländische Religionsgeschichte Herausgegeben von Irene Dingel Beiheft 129 © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666571428 | CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Confessio im Konflikt Religiöse Selbst- und Fremdwahrnehmung in der Frühen Neuzeit Ein Studienbuch Herausgegeben von Mona Garloff und Christian Volkmar Witt Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666571428 | CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Die Publikation wurde gefördert durch die Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über https://dnb.de abrufbar. © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Theaterstraße 13, D-37073 Göttingen Dieses Material steht unter der Creative-Commons-Lizenz Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0 International. Um eine Kopie dieser Lizenz zu sehen, besuchen Sie http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- nc-nd/4.0/. Satz: Vanessa Weber, Mainz Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Verlage | www.vandenhoeck-ruprecht-verlage.com ISSN 2197-1056 ISBN (Print) 978-3-525-57142-2 ISBN (OA) 978-3-666-57142-8 https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666571428 © 2019, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666571428 | CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Inhalt Vorwort .............................................................................................................. 7 Christian V. Witt Wahrnehmung, Konflikt und Confessio. Eine Einleitung ........................ -

1 INHALT Grußwort Lutherlied Familientag in Eisleben Gruppenfoto Paul Luther

INHALT Grußwort Lutherlied Familientag in Eisleben Gruppenfoto Paul Luther - der Arzt Bibliothek Familiennachrichten Kinderseite HEFT 62 90. JAHRGANG Heft 215 seit 1926 Dezember 2015 Erscheint in zwangloser Folge Teinehmer des Familientages in Eisleben versammelten sich zum traditionellen Gruppenfoto auf den Stufen des Lutherdenkmals im Zentrum der Stadt. Liebe Lutherfamilie, Haustür offenbart mir, dass nicht nur der Sommer, es kommt mir zwar so vor, als ob ich noch gestern in sondern auch schon bald das Jahr 2015 vorüber ist. der Sonne auf der Terrasse gesessen hätte - aber ein 2015 ist ein ereignisreiches Jahr, mit zahlreichen Be- Blick auf den Kalender und das Wetter vor meiner gegnungen und Zeiten des Austausches, gewesen. 1 Nicht nur für mich persönlich, sondern auch für wie auch die Bundesrepublik, wiedervereint. Ein die Lutheriden-Vereinigung. So haben wir auf dem Verdienst unserer Ehrenvorsitzenden Irene Scholvin vergangenen Familientag in Eisleben es nicht nur und ein Grund für uns, dass wir 2019 den Familien- geschafft unseren Vorstand neu zu bilden, sondern tag in Coburg begehen wollen. durften auch das neue Ahnenbuch vorstellen. Ein Viel Arbeit liegt vor dem neuen Vorstand. Seien es langwieriger, spannender und interessanter Prozess nun Nachkommenbücher, Familienblätter, Genealo- war es, der allen daran beteiligten viel Zeit abfor- gie, Bibliothek, Wahrnehmung von Einladungen zu derte. Veranstaltungen oder Arbeit an den Familientreffen. Auch wenn noch nicht alles perfekt daran ist, so wie Langweilig wird es uns zukünftig sicherlich nicht es einige Mitglieder in den vergangenen Wochen werden, das haben wir auf unserer ersten gemein- anmerkten, so ist damit meines Erachtens dennoch samen Sitzung in Berlin bei Franziska Kühnemann ein Meilenstein geschaffen, auf den wir als Vereini- bereits festgestellt. -

Lutheran Spirituality and the Pastor

Lutheran Spirituality and the Pastor By Gaylin R. Schmeling I. The Devotional Writers and Lutheran Spirituality 2 A. History of Lutheran Spirituality 2 B. Baptism, the Foundation of Lutheran Spirituality 5 C. Mysticism and Mystical Union 9 D. Devotional Themes 11 E. Theology of the Cross 16 F. Comfort (Trost) of the Lord 17 II. The Aptitude of a Seelsorger and Spiritual Formation 19 A. Oratio: Prayer and Spiritual Formation 20 B. Meditatio: Meditation and Spiritual Formation 21 C. Tentatio: Affliction and Spiritual Formation 21 III. Proper Lutheran Meditation 22 A. Presuppositions of Meditation 22 B. False Views of Meditation 23 C. Outline of Lutheran Meditation 24 IV. Meditation on the Psalms 25 V. Conclusion 27 G.R. Schmeling Lutheran Spirituality 2 And the Pastor Lutheran Spirituality and the Pastor I. The Devotional Writers and Lutheran Spirituality The heart of Lutheran spirituality is found in Luther’s famous axiom Oratio, Meditatio, Tentatio (prayer, meditation, and affliction). The one who has been declared righteous through faith in Christ the crucified and who has died and rose in Baptism will, as the psalmist says, “delight … in the Law of the Lord and in His Law he meditates day and night” (Psalm 1:2). He will read, mark, learn, and take the Word to heart. Luther writes concerning meditation on the Biblical truths in the preface of the Large Catechism, “In such reading, conversation, and meditation the Holy Spirit is present and bestows ever new and greater light and devotion, so that it tastes better and better and is digested, as Christ also promises in Matthew 18[:20].”1 Through the Word and Sacraments the entire Trinity makes its dwelling in us and we have union and communion with the divine and are conformed to the image of Christ (Romans 8:29; Colossians 3:10). -

Defending Faith

Spätmittelalter, Humanismus, Reformation Studies in the Late Middle Ages, Humanism and the Reformation herausgegeben von Volker Leppin (Tübingen) in Verbindung mit Amy Nelson Burnett (Lincoln, NE), Berndt Hamm (Erlangen) Johannes Helmrath (Berlin), Matthias Pohlig (Münster) Eva Schlotheuber (Düsseldorf) 65 Timothy J. Wengert Defending Faith Lutheran Responses to Andreas Osiander’s Doctrine of Justification, 1551– 1559 Mohr Siebeck Timothy J. Wengert, born 1950; studied at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor), Luther Seminary (St. Paul, MN), Duke University; 1984 received Ph. D. in Religion; since 1989 professor of Church History at The Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia. ISBN 978-3-16-151798-3 ISSN 1865-2840 (Spätmittelalter, Humanismus, Reformation) Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2012 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproduc- tions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by Martin Fischer in Tübingen using Minion typeface, printed by Gulde- Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. Acknowledgements Thanks is due especially to Bernd Hamm for accepting this manuscript into the series, “Spätmittelalter, Humanismus und Reformation.” A special debt of grati- tude is also owed to Robert Kolb, my dear friend and colleague, whose advice and corrections to the manuscript have made every aspect of it better and also to my doctoral student and Flacius expert, Luka Ilic, for help in tracking down every last publication by Matthias Flacius. -

Abuses Under Indictment at the Diet of Augsburg 1530 Jared Wicks, S.J

ABUSES UNDER INDICTMENT AT THE DIET OF AUGSBURG 1530 JARED WICKS, S.J. Gregorian University, Rome HE MOST recent historical scholarship on the religious dimensions of Tthe Diet of Augsburg in 1530 has heightened our awareness and understanding of the momentous negotiations toward unity conducted at the Diet.1 Beginning August 16, 1530, Lutheran and Catholic represent atives worked energetically, and with some substantial successes, to overcome the divergence between the Augsburg Confession, which had been presented on June 25, and the Confutation which was read on behalf of Emperor Charles V on August 3. Negotiations on doctrine, especially on August 16-17, narrowed the differences on sin, justification, good works, and repentance, but from this point on the discussions became more difficult and an impasse was reached by August 21 which further exchanges only confirmed. The Emperor's draft recess of September 22 declared that the Lutheran confession had been refuted and that its signers had six months to consider acceptance of the articles proposed to them at the point of impasse in late August. Also, no further doctrinal innovations nor any more changes in religious practice were to be intro duced in their domains.2 When the adherents of the Reformation dis sented from this recess, it became unmistakably clear that the religious unity of the German Empire and of Western Christendom was on the way to dissolution. But why did it come to this? Why was Charles V so severely frustrated in realizing the aims set for the Diet in his conciliatory summons of January 21, 1530? The Diet was to be a forum for a respectful hearing of the views and positions of the estates and for considerations on those steps that would lead to agreement and unity in one church under Christ.3 1 The most recent stage of research began with Gerhard Müller, "Johann Eck und die Confessio Augustana/' Quellen und Forschungen aus italienischen Archiven und Biblio theken 38 (1958) 205-42, and continued in works by Eugène Honèe and Vinzenz Pfhür, with further contributions of G. -

The German Military Entrepreneur Ernst Von Mansfeld and His Conduct of Asymmetrical Warfare in the Thirty Years War

UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI The German Military Entrepreneur Ernst von Mansfeld and His Conduct of Asymmetrical Warfare in the Thirty Years War Olli Bäckström 15.9.2011 Pro Gradu Yleinen historia Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................3 1.1 Ernst von Mansfeld ........................................................................................................................3 1.2 Theoretical Approach and Structure ..............................................................................................4 1.3 Primary Sources .............................................................................................................................7 1.4 Secondary Sources and Historiography .........................................................................................8 1.5 Previous Research on the Thirty Years War as an Asymmetrical Conflict .................................10 2. OPERATIONALLY ASYMMETRICAL WARFARE.................................................................12 2.1 Military Historiography and the Thirty Years War .....................................................................12 2.2 The Origins of Habsburg Warfare ...............................................................................................14 2.3 Mansfeld and Military Space .......................................................................................................16 2.4 Mansfeld and Mobile Warfare .....................................................................................................19