Constitutional Adjudication by Parliaments: Experiences Across Time and Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bi-Cameralism Under the New Constitution the Legislature: Bi-Cameralism Under the New Constitution

Constitution Working Paper Series No. 8 The Legislature: Bi-Cameralism under the new Constitution The Legislature: Bi-Cameralism under the new Constitution The Legislature: Bi-Cameralism under the new Constitution Kipkemoi arap Kirui and Kipchumba Murkomen SID Constitution Working Paper No. 8 ii The Legislature: Bi-Cameralism under the new Constitution The Legislature: Bi-Cameralism under the new Constitution Constitution Working Paper No. 8 Published by: Society for International Development (SID) Regional Office for East & Southern Africa Britak Centre, First Floor Ragati/Mara Road P.O. Box 2404-00100 Nairobi, Kenya Tel. +254 20 273 7991 Fax + 254 20 273 7992 www.sidint.net © Society for International Development (SID), 2011 ISBN No. 978-9966-029-07-2 Printed by: The Regal Press Kenya Ltd. P.O. Box 46166 Nairobi, Kenya Design & Layout: Sunburst Communications Ltd. P.O. Box 43193-00100 Nairobi, Kenya Email: [email protected] SID Constitution Working Paper No. 8 The Legislature: Bi-Cameralism under the new Constitution iii Abstract The aims of this paper are threefold. First, the paper retraces the history of the Kenyan legislature before and after independence tracking the various transformations spanning a century of its existence. These transformations have been largely characterised by two competing forces: one epitomized by a strong executive seizing power from other arms of government, and the other by pro-reform forces pushing for an expanded democracy, better governance and accountability, and the promotion of rule of law. They agitated for electoral, legislative and constitutional reforms resulting in the reduction of the powers of the president, the re-introduction of multiparty democracy and the expansion of people’s democratic space and shifting power from the presidency back to other arms of the state, including parliament, and by extension to the people. -

The Jurisprudence and Approaches of Constitutional Interpretation by the House of Federation in Ethiopia

The Jurisprudence and Approaches of Constitutional Interpretation by the House of Federation in Ethiopia Anchinesh Shiferaw Mulu . Abstract This article examines the jurisprudence of the Council of Constitutional Inquiry (CCI) and the House of Federation (HoF) in resolving constitutional disputes with a view to identifying the principles/approaches utilized in their decisions and its human rights implication. These organs are entrusted with the power to interpret the Constitution upon application by private parties or court referral of cases. The article also examines patterns in the judiciary’s referral of cases for constitutional interpretation, and it discusses the methods and principles used by CCI/HoF in constitutional interpretation. Although the CCI/HoF has not expressly adopted distinct principles/approaches of constitutional interpretation, they can be inferred from the jurisprudence of the CCI and the HoF. I argue that there is inconsistent application of principles of constitutional interpretation. This is related with the incoherence observed in the constitutional interpretation of fundamental human rights recognized under the FDRE Constitution and ratified international human rights conventions. This shows that the HoF –which is a political body– has failed to protect basic human rights through its decisions that involve politically sensitive cases. There is thus the need to develop and adopt rules of procedure and principles of constitutional interpretation that can ensure predictability, consistency and coherence in HOF/CCI decisions towards the protection of human rights. Key terms Human rights · Constitutional interpretation · House of Federation · Council of Constitutional Inquiry DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/mlr.v13i3.4 This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) Suggested citation: Mulu, Anchinesh Shiferaw (2019), ‘The Jurisprudence and Approaches of Constitutional Interpretation by the House of Federation in Ethiopia’, Mizan Law Review, Vol. -

Between Secession and Federalism: the Independence of South Sudan and the Need for a Reconsidered Nigeria Obehi S

Global Business & Development Law Journal Volume 26 | Issue 2 Article 2 1-1-2013 Between Secession and Federalism: The Independence of South Sudan and the Need for a Reconsidered Nigeria Obehi S. Okojie Adeleke Adeyemo & Co., Lagos, Nigeria Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/globe Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Obehi S. Okojie, Between Secession and Federalism: The Independence of South Sudan and the Need for a Reconsidered Nigeria, 26 Pac. McGeorge Global Bus. & Dev. L.J. 415 (2013). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/globe/vol26/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Law Reviews at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Global Business & Development Law Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. [2] OBEHI.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 5/10/2013 11:16 AM Between Secession and Federalism: The Independence of South Sudan and the Need for a Reconsidered Nigeria Obehi S. Okojie* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 416 II. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................ 420 A. Nigeria and Sudan at a Glance ............................................................. 420 B. Similar Features -

Sub-National Second Chambers and Regional Representation: International Experiences Submission to Kelkar Committee on Maharashtra

Sub-national Second Chambers and regional representation: International Experiences Submission to Kelkar Committee on Maharashtra By Rupak Chattopadhyay October 2011 The principle of the upper house of the legislature being a house of legislative review is well established in federal and non-federal countries like. Historically from the 17th century onwards, upper houses were constituted to represent the legislative interests of conservative and corporative elements (House of Lords in the UK or Senate in Bavaria or Bundesrat in Imperial Germany) against those of the ‘people’ as represented by elected lower houses (e.g. House of Commons). The United States became the first to use the upper house as the federating chamber for the country. This second model of bicameralism is that associated with the influential ‘federal’ example of the US Constitution, in which the second chamber was conceived as a ‘house of the states’. It has been said in this regard that federal systems of government are highly conducive to bicameralism in which a senate serves as a federal house whose members are selected to represent the states or provinces, with each constituent state provided equal representation. The Australian Senate was conceived along similar lines, with the Constitution guaranteeing each state, again regardless of its population, an equal number of senators. At present, the Australian Senate consists of 76 senators, 12 from each of the six states and two from each of the mainland territories.60 The best contemporary example of a second chamber which does, in fact, operate as an effective ‘house of the states’ is the German Bundesrat, members of which are appointed by state governments from amongst their members, with each state having between three and six representatives, depending on population. -

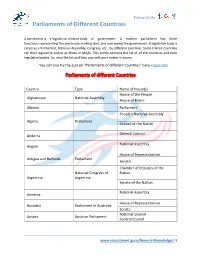

Parliaments of Different Countries

Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries A parliament is a legislative, elected body of government. A modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government. A legislative body is called as a Parliament, National Assembly, Congress, etc., by different countries. Some Islamic countries call their legislative bodies as Shora or Majlis. This article contains the list of all the countries and their legislative bodies. So, read the list and help yourself score better in exams. You can also try the quiz on “Parliaments of different Countries” here – Quiz Link Parliaments of different Countries Country Type Name of house(s) House of the People Afghanistan National Assembly House of Elders Albania Parliament People's National Assembly Algeria Parliament Council of the Nation General Council Andorra National Assembly Angola House of Representatives Antigua and Barbuda Parliament Senate Chamber of Deputies of the National Congress of Nation Argentina Argentina Senate of the Nation National Assembly Armenia House of Representatives Australia Parliament of Australia Senate National Council Austria Austrian Parliament Federal Council www.recruitment.guru/General-Knowledge/|1 Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries Azerbaijan National Assembly House of Assembly Bahamas, The Parliament Senate Council of Representatives Bahrain National Assembly Consultative Council National Parliament Bangladesh House of Assembly Barbados Parliament Senate House of Representatives National Assembly -

African Parliaments: Between Governance and Government

African Parliaments This page intentionally left blank 01_Mohamed_FM.qxd 20/9/05 5:21 PM Page iii African Parliaments Between Governance and Government Edited by M.A. Mohamed Salih 01_Mohamed_FM.qxd 21/9/05 3:49 PM Page iv AFRICAN PARLIAMENTS © M.A. Mohamed Salih, 2005. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published in 2005 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 1–4039–7122–6 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Design by Newgen Imaging Systems (P) Ltd., Chennai, India. First edition: December 2005 10987654321 Printed in the United States of America. 01_Mohamed_FM.qxd 20/9/05 5:21 PM Page v Contents List of Figures and Tables vii List of Abbreviations and Acronyms ix Notes on Contributors xiii Preface xvii PART I 1. Introduction: The Changing Governance Role of African Parliaments 3 M.A. Mohamed Salih 2. Parliaments, Politics, and Governance: African Democracies in Comparative Perspective 25 Wil Hout 3. -

Minority Rights Protection Under the Second House: the Ethiopian Federal Experience

Vol. 11(6), pp. 144-149, June 2017 DOI: 10.5897/AJPSIR2016.0969 Article Number: 2C7F74464310 African Journal of Political Science and ISSN 1996-0832 Copyright © 2017 International Relations Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJPSIR Review Minority rights protection under the second house: The Ethiopian federal experience Alene Agegnehu* and Worku Dibu Department of Civic and Ethical Studies, Adigrat University, P. O. Box 50, Adigrat, Ethiopia. Received 21 November, 2016; Accepted 20 March, 2017 Right after the overthrow of dictatorial military regime since 1991, Ethiopia underwent a remarkable change of political system. It has restructured the society based on federal state arrangement which creates nine self-administered regional government taking linguistic, settlement pattern, and consent of the governed into consideration. Addis Ababa and although not mentioned in the constitution, Dire Dawa become autonomous city administration outside regional sphere of competence but administered and responsible to the federal government. The federal arrangement further creates Bi-cameral federal institutions, House of People Representatives and House of Federation for the site of regional people representatives and minorities that are found within the regional government, respectively. Under the house of people representative, out of 548 seats, 20 are lefts and reserved for minority groups. Under house of federation, this is commonly understood as the house of minorities in which every nation, nationality and people of Ethiopia have representative that reflect the interests of their minority groups. Every nation, nationality and people has a minimum of one representative and possibly to have additional representative based on their population number. -

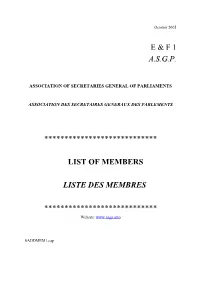

List of Members: October 2005 | Liste Des Membres: Octobre 2005

October 2005 E & F 1 AA..SS..GG..PP.. ASSOCIATION OF SECRETARIES GENERAL OF PARLIAMENTS ASSOCIATION DES SECRETAIRES GENERAUX DES PARLEMENTS **************************** LIST OF MEMBERS LISTE DES MEMBRES **************************** Website: www.asgp.info SADDMEM1.cap - 2 - I.- PRESIDENCY AND SECRETARIAT PRESIDENCE ET SECRETARIAT PRESIDENT: Mr Anders FORSBERG Secretary General of the Riksdagen, S-100 12 Stockholm Tel: (46) 8-786 40 00. Fax : (46) 8-786 6143. E-mail: [email protected] JOINT SECRETARIES/CO-SECRETAIRES Roger Phillips Frederic Slama Committee Office Administrateur House of Commons Services des Relations Internationales London SW1A 0AA Assemblée nationale United Kingdom 126 rue de l'Université 75355, Paris 07 SP Tel: (44) 20 7219 8195 Tél: (33) 1 4063 8441 Fax: (44) 20 7219 0843 Fax: (33) 1 4063 8949 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] II.- LIST OF MEMBERS/ LISTE DES MEMBRES This list is revised after each session of the Association. Please notify one of the joint secretaries of any changes. Cette liste est périodiquement révisée ; vous pouvez donc faire part au secrétariat de toutes les modifications qui interviennent en cours d'année. Albania **(E) Artan BANUSHI, Secretary General of the Parliament of Albania, Kuvendi 1 Rep Albanie Shqiperise, Tirana. Tel: (355) 423 4618. Fax (355) 422 8688. E-mail: [email protected] Website: www. parlament.al Algeria **(F) Boubeker ASSOUL , Secrétaire général de l Assemblée populaire nationale, Algérie 18, Boulevard Zirout Youcef, Alger. Tél: (213.21) 74 01 74. Fax: (213.21) 74 03 89. E-mail: [email protected] **(F) Dr Hafnaoui AMRANI, Secrétaire général du Conseil de la Nation, 07 Palais Zighout Youcef, Alger. -

The Forum of Federations Is Supported By

THE FORUM OF FEDERATIONS IS SUPPORTED BY: Switzerland: Brazil: European Union: Conference of Cantonal Presidency of the Republic European Development Fund Governments Canada: Germany: Switzerland: Global Affairs Canada Federal Ministry of the Interior, Federal Department of Building and Community Justice and Police Quebec: Ireland: Switzerland: Secrétariat du Québec aux relations Department of Foreign Affairs Swiss Development Cooperation canadiennes, GoQ Denmark: Netherlands: UK: Ministry of Foreign Affairs Ministry for Trade and Development Department for International Cooperation Development Ethiopia: House of Federation The Forum of Federations, the global network on federalism and TABLE OF CONTENTS multi-level governance, supports better governance through learning MESSAGE FROM THE FORUM OF FEDERATIONS ................................................. 4 among practitioners and experts. BOARD OF DIRECTORS ........................................................................................... 5 Active on six continents, it runs programs in over 20 countries, FORUM STAFF .......................................................................................................... 7 including established federations WHO WE ARE AND WHAT WE DO ........................................................................... 9 and countries transitioning to devolved and decentralized forms of POLICY PROGRAMS .............................................................................................. 13 governance. DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE PROGRAMS -

E & F 1 Asgp **************************** List Of

October 2016/octobre 2016 E & F 1 A.S.G.P. ASSOCIATION OF SECRETARIES GENERAL OF PARLIAMENTS ASSOCIATION DES SECRÉTAIRES GÉNÉRAUX DE PARLEMENT **************************** LIST OF MEMBERS LISTE DES MEMBRES **************************** Website: www.asgp.co I.- PRESIDENCY AND SECRETARIAT PRESIDENCE ET SECRETARIAT PRESIDENT: Mrs. Doris Katai Katebe MWINGA Clerk of the National Assembly Parliament Buildings P.O. Box 31299 Lusaka 10101, ZAMBIA Tel: (260) 211 292 425 / 293 352 Fax: (260) 211 292 252 E-mail: [email protected] Web : www.parliament.gov.zm JOINT SECRETARIES/CO-SECRETAIRES Mrs. Emily Commander Mme. Inés Fauconnier c/o Daniel Moeller Assemblée nationale Transport Committee 95, rue de l’Université House of Commons 75355, Paris 07 SP Palace of Westminster France London SW1A0AA United Kingdom. Tel: (44) 20 7219 3266 Tél: (33) 1 40 63 2535 Fax: (33) 1 40 63 5759 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Page 2 of 35 II.- LIST OF MEMBERS LISTE DES MEMBRES Afghanistan *# (E) Mr. Sayed Hafizullah HASHIMI, Secretary General of the House of Afghanistan Elders (Meshrano Jirga), Afghan National Assembly, Darul-Aman Avenue, Kabul. Tel.: (93) 708822222 / 0700290933. E-mail: [email protected] (E) N……………………, Deputy Secretary General of the House of Elders (Meshrano Jirga), National Assembly Building, Darul-Aman Avenue, Kabul City. Tel.: (93) 799 553 593. E-mail: [email protected] *# (E) Mr. Khudai Nazar NASRAT, Secretary General of the House of the People (Wolesi Jirga), National Assembly of Afghanistan, Darul-Aman Avenue, Parliament Complex, Kabul. Tel.: (93) 786 125 500. E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.parliament.af (E) Mr. -

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia)

Ethiopia (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia) TOM PÄTZ 1 history and development of federalism The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (appoximately 1,127,000 km2) is located at the Horn of Africa. It is bordered by Sudan on the west, Kenya on the south, Somalia and Djibouti on the east, and Eritrea on the north. It has a population of some 67 million inhabitants, about 90 per cent of whom earn their living from the land, mainly as subsis- tence farmers. Agriculture is the backbone of the national economy. The country has a Gross National Product (gnp) per capita of just us$90, making it the poorest country in the world in 2003, according to the World Bank. Life expectancy at birth is less than 45 years. Due to its 3,000-year history, Ethiopia is seen as the oldest “state” in Africa and one of the oldest in the world. Starting from the Da’amat State (ca. 500 bc-100 ad), followed by the advanced civilization of the Axumite Empire and finally the Era of the Princes, Ethiopia has existed within different patrimonial empires. Modern Ethiopia was created by Christian highland rulers largely through twin processes of political subjugation and economic exploitation in the late nine- teenth and early twentieth centuries. The Imperial Crown Prince and Regent, Haile Selassie, established ascendancy over regional feudal lords from 1916 to 1930, when he became Emperor. Haile Selassie was driven into exile during the Italian occupation of Ethiopia be- tween 1936 and 1941. Following the country’s liberation by Allied forces in 1941, he returned from Britain and ruled until his over- throw in 1974. -

Second Chambers

Library Note Second Chambers This Library Note looks at bicameral legislatures in other parts of the world and provides an overview of some of the features of other second chambers, and how these compare to the current House of Lords. The Note is intended as a short reference guide, and looks at the size of the second chambers; membership terms; and methods of selecting members. The Note concludes with a brief discussion of the powers of second chambers. Heather Evennett 10 March 2014 LLN 2014/010 House of Lords Library Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of the House of Lords and their personal staff, to provide impartial, politically balanced briefing on subjects likely to be of interest to Members of the Lords. Authors are available to discuss the contents of the Notes with the Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. Any comments on Library Notes should be sent to the Head of Research Services, House of Lords Library, London SW1A 0PW or emailed to [email protected]. Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Unicameral Compared to Bicameral Legislatures ................................................................................ 2 3. The Size of Second Chambers .................................................................................................................. 3 4. Membership Terms ....................................................................................................................................