Censoring the Prophetic How Constantinian and Progressive Jews Censor Debate About the Future of the Jewish and Palestinian People Marc H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Day of Judaism in the Catholic Church of Poland

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs) Spring 5-18-2015 The aD y of Judaism in the Catholic Church of Poland Piotr Dudek Seton Hall University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Dudek, Piotr, "The aD y of Judaism in the Catholic Church of Poland" (2015). Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs). 2098. https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/2098 The Day of Judaism in the Catholic Church of Poland by Piotr Dudek Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Department of Religion Seton Hall University May 2015 © 2015 Piotr Dudek 2 SETON HALL UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION APPROVAL FOR SUCCESSFUL DEFENSE Master’s Candidate, Piotr Dudek , has successfully defended and made the required modifications to the text of the master’s thesis for the M.A. during this Spring Semester 2015 . DISSERTATION COMMITTEE (please sign and date beside you name) The mentor and any other committee members who wish to review revisions will sign and date this document only when revisions have been completed. Please return this form to the Office of Graduate Studies, where it will be placed in the candidate’s file and submit a copy with your final diss ertation. 3 Abstract: The Day of Judaism in the Catholic Church of Poland This master’s thesis discusses “The Day of Judaism in the Catholic Church of Poland,” a special time in the Polish Church calendar to rediscover her roots in Judaism. -

Glossary, Evaluations, Resources, and Bibliography. C/JEEP

GLOSSARY Aggadah. Rabbinic teaching which amplifies biblical narrative, history and ethics; found throughout Talmud; includes parables, allegories, theology Aliyah. Lit. "going up." (I) calling up a member of the congregation to read from the Torah; (II) term used to describe immigration of Jews to Israel Annunciation. The Christian celebration of the announcement of the incarna- tion (Luke 1:28-35) Anti-Semitism. Hatred of the Jewish people; term coined in 1879 to designate anti-Jewish campaigns in Europe; became a general term to denote all forms of hostility toward Jews through the centuries Apocrypha. Seven books included in the Roman Catholic Bible that constitute a separate section of the Protestant Bible Apostle. Member of authoritative New Testament group sent out to preach the gospel; especially refers to Jesus' twelve original disciples Ark. (Hebrew: awn kodesh); cabinet in the synagogue containing the Torah scrolls Ascension. Christian reference to Jesus' ascension into heaven Ashkenazim. One of two main divisions of Jewry in the Diaspora; originally referred to German Jewry, later came to designate Jews of France, Poland, Russia, and Scandinavia. Most American Jews are Ashkenazim Assumption. In Christianity, the taking up of a person to heaven; refers esp. to Mary Bar mitzvah. "Son of the Commandment"; special synagogue service at which Jewish boys (age 13) mark attainment of legal and religious maturity by reading from Torah and Haftorah Bat mitzvah. "Daughter of the Commandment"; ceremony for girls (age 12) corresponding to boys' bar mitzvah Bimah. "Elevated place"; platform in synagogue where Torah is read Breviary. A book containing the prayers, hymns, psalms, and readings for the Roman Catholic Church Brit milah. -

1 Beginning the Conversation

NOTES 1 Beginning the Conversation 1. Jacob Katz, Exclusiveness and Tolerance: Jewish-Gentile Relations in Medieval and Modern Times (New York: Schocken, 1969). 2. John Micklethwait, “In God’s Name: A Special Report on Religion and Public Life,” The Economist, London November 3–9, 2007. 3. Mark Lila, “Earthly Powers,” NYT, April 2, 2006. 4. When we mention the clash of civilizations, we think of either the Spengler battle, or a more benign interplay between cultures in individual lives. For the Spengler battle, see Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996). For a more benign interplay in individual lives, see Thomas L. Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1999). 5. Micklethwait, “In God’s Name.” 6. Robert Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). “Interview with Robert Wuthnow” Religion and Ethics Newsweekly April 26, 2002. Episode no. 534 http://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/week534/ rwuthnow.html 7. Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity, 291. 8. Eric Sharpe, “Dialogue,” in Mircea Eliade and Charles J. Adams, The Encyclopedia of Religion, first edition, volume 4 (New York: Macmillan, 1987), 345–8. 9. Archbishop Michael L. Fitzgerald and John Borelli, Interfaith Dialogue: A Catholic View (London: SPCK, 2006). 10. Lily Edelman, Face to Face: A Primer in Dialogue (Washington, DC: B’nai B’rith, Adult Jewish Education, 1967). 11. Ben Zion Bokser, Judaism and the Christian Predicament (New York: Knopf, 1967), 5, 11. 12. Ibid., 375. -

Elkin, Judith Laikin. "Jews and Non-Jews. " the Jews of Latin America. Rev. Ed. New York

THE JEWS OF LATIN AMERICA Revised Edition JUDITH LAIKIN ELKIN HOLMES & MEIER NEW YORK / LONDON Published in the United Stutes of America 1998 b y ll olmes & Meier Publishers. Inc . 160 Broadway ew York, NY 10038 Copyr ight © 199 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, 1.nc. F'irst edition published und er th e title Jeics of the u1tl11A111erica11 lle1'11hlics copyright © 1980 The University of o rth Ca rolina Press . Chapel Hill , NC . All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any elec troni c o r mechanical means now known or to be invented, including photocopying , r co rdin g, and information storage and retrieval systems , without permission in writing from the publishers , exc·ept by a reviewe r who may quote brief passages in a review. The auth or acknow ledges with gra titud e the court esy of the American Jewish lli stori cal Society to reprint the follo,ving articl e which is published in somewhat different form in this book: "Goo dnight , Sweet Gaucho: A Revisio nist View of the Jewis h Agricultural Experiment in Argentina, " A111eric1111j etds h Historic(I/ Q11111terly67 (March 1978 ): 208 - 23. Most of the photographs in this boo k were includ d in the exhibit ion . "Voyages to F're dam: .500 Years of Je,vish Li~ in Latin America and the Caribbean ," and were ma de availab le throu ,I, the court esy of the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith . Th e two photographs of the AMIA on pages 266 - 267 we re s uppli ed by the AMIA -Co munidad Judfa de Buenos Aires. -

Jews and Christians, Fellow Travelers to the End of Days (Daniel 12)

Jew s and C hristians, Fellow T ravelers to the E nd of D ays JEWS AND CHRISTIANS UNITED FOR ISRAEL provides both Jews and Christians with an association through which, together, they can show their support for Israel and stand Jews and Christians, united against all forms of theological, cultural and political anti-Semitism. Anti-Semitism is an assault on God, as well as on the Jewish people. Fellow Travelers to Come let us go up to the Mountain of the Lord, to the Temple of the God of Jacob, and He will teach us of His Ways and we will walk in the End of Days His paths. For from Zion will the Torah come forth, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem. (Isaiah 2:3) Martin M. van Brauman, the president of Jews and Christians United For Israel, Inc., is also the Corporate Secretary, Treasurer, Senior Vice President and Director of Zion Oil & Gas, Inc. He is the managing director of e Abraham Foundation (Geneva, Switzerland) and the Bnei Joseph Foundation (Israeli Amuta). He is a Texas board member of the Bnai Zion Foundation, an Advisory Board Member on the Jewish and Israel Studies Program at the University of North Texas and an AIPAC B Capitol Club member. www.jewsandchristiansunitedforisrael.org M M. B JEWS AND CHRISTIANS, FELLOW TRAVELERS TO THE END OF DAYS (DANIEL 12) MARTIN M. VAN BRAUMAN Copyright © 2011 by Martin M. Van Brauman Second Edition 2020 Published in The United States of America by JEWS AND CHRISTIANS UNITED FOR ISRAEL, INC. 12655 North Central Expressway, Suite 1030 Dallas, Texas 75243 www.JewsandChristiansunitedforIsrael.org All rights reserved. -

The Catholic-Jewish and Polish-Jewish Dialogue in New Poland

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 13 Issue 6 Article 3 12-1993 The Catholic-Jewish and Polish-Jewish Dialogue in New Poland Waldemar Chrostowski Academy of Catholic Theology, Warsaw, Poland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chrostowski, Waldemar (1993) "The Catholic-Jewish and Polish-Jewish Dialogue in New Poland," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 13 : Iss. 6 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol13/iss6/3 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. •.. '··~ ~ .. -: .. I . ~'. 1: ,. .... ·. ·""- .... THE CATHOLIC-JEWISH AND POLISH-JEWISH DIALOGUE IN NEW, POLAND . "": .... ;. ,., _;· . ·;. ' ; ."· .. by Waldemar Chrostowski Dr. Waldemar Chrostowski is a Roman Catholic priest and lecturer of the Old Testament exegesis and theology at Academy of Catholic Theology (ACT) in Warsaw; since 1989 has been organizing Christian-Jewish theological symposia at ACT and is editor-in-chief of the series "The Church, Jews and Judaism"; coordinator and spokesman of the seminar at Spertus College of JudaiCa in Chicago (1989), member of the Polish Bishops' Commission for the Dialogue with Judaism, the Presidential Commission on Polish-Jewish Relations, the International Council of the State Museum in Oswiecim, the Council of the Foundation for the Commemoration of the Victim of Auschwitz-Birkenau Extermination Camp, initiated and co-chairs the Polish Council of Christians and Jews, a Board member of the Polish-Israeli Friendship Association. -

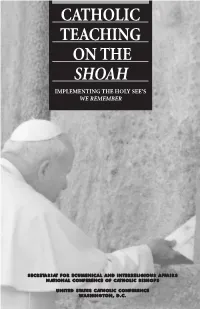

Catholic Teaching on the Shoah Implementing the Holy See’S We Remember

CATHOLIC TEACHING ON THE SHOAH IMPLEMENTING THE HOLY SEE’S WE REMEMBER S E C R E TA R I AT F O R E C U M E N I C A L A N D I N T E R R E L I G I O U S A F FA I R S N AT I ON AL CO NFE RENC E O F CAT H O L I C B I S H O P S U N I T E D S TAT E S C AT HO LI C CO NF ERE NCE WA S H I N G T O N , D . C . At its November 1999 meeting, the Bishops’ Committee for Ecumenical and Interreligious Relations discussed and approved the publication of these reflections as a resource for use on all levels of Catholic education. At its September 2000 meeting, the Administrative Committee of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops also dis- cussed and approved it for publication. It has been reviewed by Bishop Tod D. Brown, the chairman of the BCEIA and approved for publication by the undersigned. Msgr. Dennis M. Schnurr General Secretary, NCCB/USCC Cover: Pope John Paul II at Western Wall in Jerusalem, March 26, 2000. Photo by CNS/Reuters. List of resources based in part on a bibliography compiled by Ned Shulman, © 1990, for The Holocaust: A Guide for Pennsylvania Teachers, by Gary M. Grobman. Used with permission from the copyright holder. First Printing, February 2001 ISBN 1-57455-406-9 Copyright © 2001, United States Catholic Conference, Inc., Washington, D.C. -

Dead Jewish Other in Poland: Spectrality, Embodiment and Polish Holocaust Horror in Władysław Pasikowski’S Aftermath (2012)

genealogy Article Memorialising the (Un)Dead Jewish Other in Poland: Spectrality, Embodiment and Polish Holocaust Horror in Władysław Pasikowski’s Aftermath (2012) Emily-Rose Baker School of English, University of Sheffield, Sheffield S10 2TN, UK; erbaker1@sheffield.ac.uk Received: 4 September 2019; Accepted: 20 November 2019; Published: 29 November 2019 Abstract: This article analyses the function and symbolic currency of Poland’s recent literary and artistic motif of the returning Jew, which brings the nation’s Jewish Holocaust victims back to their homes as ghosts, spectres and reanimated corpses. It explores the ability of this trope—the defining feature of what I call ‘Polish Holocaust horror’—to cultivate the memory of complicitous and collaborative Polish behaviour during the Holocaust years, and to promote renewed Polish-Jewish relations based upon a working-through of this difficult history. In the article I explore Władysław Pasikowski’s 2012 film Aftermath as a self-reflexive product of this experimental genre, which has been considered ethically ambiguous for its necropolitical treatment of Jews and politically controversial for its depiction of Poles as perpetrators. My analysis examines haunting as central to these popular cultural constructions of Holocaust memory—a device that has been used within the genre to mourn but also expel guilt for the previously forgotten or supressed dispossession and murder of Jews by some of their Polish neighbours. Keywords: haunting; cultural memory; Holocaust fiction; Polish-Jewish relations; Jedwabne; spectrality; ghosts 1. Introduction During the 2010 performance of the first quasi-fictional1 International Congress of the Jewish Renaissance Movement in Poland (JRMiP), held at Berlin’s Hebbel am Ufer performance space, Israeli director and artist Yael Bartana issued a ‘manifesto’ pertaining to the group’s hypothetical mission. -

Immigrants of a Different Religion: Jewish Argentines

IMMIGRANTS OF A DIFFERENT RELIGION: JEWISH ARGENTINES AND THE BOUNDARIES OF ARGENTINIDAD, 1919-2009 By JOHN DIZGUN A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History written under the direction of Samuel L. Baily and approved by New Brunswick, New Jersey October, 2010 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Immigrants of a Different Religion: Jewish Argentines and the Boundaries of Argentinidad, 1919-2009 By JOHN DIZGUN Dissertation Director: Samuel L. Baily This study explores Jewish and non-Jewish Argentine reactions and responses to four pivotal events that unfolded in the twentieth century: the 1919 Semana Trágica, the Catholic education decrees of the 1940s, the 1962 Sirota Affair, and the 1976-1983 Dirty War. The methodological decision to focus on four physically and/or culturally violent acts is intentional: while the passionate and emotive reactions and responses to those events may not reflect everyday political, cultural, and social norms in twentieth-century Argentine society, they provide a compelling opportunity to test the ever-changing meaning, boundaries, and limitations of argentinidad over the past century. The four episodes help to reveal the challenges Argentines have faced in assimilating a religious minority and what those efforts suggest about how various groups have sought to define and control what it has meant to be “Argentine” over time. Scholars such as Samuel Baily, Fernando DeVoto, José Moya and others have done an excellent job highlighting how Italian and Spanish immigrants have negotiated and navigated the ii competing demands of ‘ethnic’ preservation and ‘national’ integration in Argentina. -

Rabbi León Klenicki (1930-2009 )

Contemporary Voices in Jewish-Christian Dialogue #5 Rabbi León Klenicki (1930-2009 ) Rabbi León Klenicki, one of the most passionate and prolific modern Jewish voices in interreligious dialogue, was born on September 7, 1930 in Buenos Aires, Argentina, to parents who had emigrated from Poland in the previous decade. In 1959, Léon received a scholarship to study in the United States, at Cincinnati’s Hebrew Union College. After initial studies in philosophy, he graduated with a Masters degree and received his rabbinic ordination in 1967 from Hebrew Union College, having intensively studied the field of interfaith dialogue. Returning to his native Argentina, he became the rabbi of Congregation Emanu-El in Buenos Aires, and director of the Latin American arm of the World Union for Progressive Judaism. It was in that second capacity that, in 1968, Klenicki took part in the first-ever formal gathering of Latin American Christian and Jewish leaders, held in Bogotá, Colombia, addressing the participants on the shared Scriptural bonds linking Jews and Christians, but also recalling the long Christian history of persecuting Jews; the Middle Ages, he said, were a time when “cathedrals were raised to the sky while Jews had to go underground”. And yet, with a nod to recent changes in Church teaching, he acknowledged: “The time of hope has arrived. The task is hard, but not impossible.” He would lecture widely in Latin American centres, inaugurated a study of attitudes toward Jews in Latin American religious textbooks, and began a magazine called Teshuvah (Hebrew for “repentance”) , to explore Jewish thought. Throughout his life, he remained a leading figure in the Reform movement of Judaism, especially in Spanish-speaking countries, editing and publishing numerous liturgical and educational texts aimed at meeting the needs of local communities. -

Cardinal Presents Papal Order of St. Gregory to Rabbi Leon Klenicki

March 22, 2007 - Cardinal Presents Papal Order Of St. Gregory To Rabbi Leon Klenicki Brighton, MA -- Cardinal Seán P. O’Malley announced that His Holiness, Pope Benedict XVI, has named Rabbi Leon Klenicki to the Papal Order of St. Gregory. The Cardinal made this announcement during the Anti-Defama- tion League’s “Nation of Immigrants” Community Seder on Thursday, March 22, 2007 at The Castle at Park Plaza. Cardinal Seán said, “Rabbi Klenicki has been a pioneer in Jewish-Catholic relations for decades. His own personal experiences of anti-Semitism led the Rabbi to be a passionate advocate for education as means of dispelling religious prejudice and promoting interreligious collaboration.” The Cardinal noted that, “On the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the arsawW ghetto uprising, Pope John Paul II said, ‘As Christians and Jews, following the example of the faith of Abraham, we are called to be a blessing to the world. This is the common task awaiting us. It is therefore necessary for us, Christians and Jews, to first be a blessing to one another.’ Rabbi Leon Klenicki’s life has been the source of blessings for all of us. We are deeply grateful for his witness and his work.” In naming Rabbi Leon Klenicki to the Papal Order of Saint Gregory, Pope Benedict XVI has bestowed the highest honor the Catholic Church confers on a layperson, in recognition of “Outstanding Services Rendered to the Welfare of Society and the Church”. This Pontifical Honor of Knighthood is conferred by the Holy Father on his own initiative and at the recommendation of diocesan bishops who present worthy candidates to the Holy Father. -

Joint Communiqué

International Catholic - Jewish Liaison Committee 17th Meeting New York City, May 1-3, 2001 Joint Communiqué Following the Second Vatican Council in 1965, the Catholic Church and international groups representing the Jewish People both in Israel and in the Diaspora determined to establish together a mechanism to follow through on the extraordinary moment in history represented by the Council's Declaration, Nostra Aetate ("In Our Time"). After nearly two millennia of polemical relations, a window was opened to allow dialogue to replace the disputations of the past. The result was the establishment of the International Catholic - Jewish Liaison Committee ("ILC") between the Holy See’s Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews and the International Jewish Committee for Interreligious Consultations ("IJCIC") IJCIC is comprised of the American Jewish Committee, the Anti-Defamation League, B'nai B'rith International, the Central Conference of American Rabbis, Israel Jewish Council for Interreligious Relations, the Rabbinical Assembly, the Rabbinical Council of America, the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America, the United Synagogue of America, and the World Jewish Congress. The 17th meeting occurred May 1-3, 2001 in New York City. In the years following the 16th meeting (which was held in Vatican City in March of 1998) tensions arose between the Holy See's Commission and IJCIC. The Catholic side was frustrated by the lack of theological dialogue. The Jewish side responded that it wanted to deepen the dialogue in a way Jews and Catholics could learn about each other and project our communities accurately without risking theological disputations.