The Teaching of the Second Vatican Council on Jews and Judaism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catholicism HDT WHAT? INDEX

ST. BERNARD’S PARISH OF CONCORD “I know histhry isn’t thrue, Hinnissy, because it ain’t like what I see ivry day in Halsted Street. If any wan comes along with a histhry iv Greece or Rome that’ll show me th’ people fightin’, gettin’ dhrunk, makin’ love, gettin’ married, owin’ th’ grocery man an’ bein’ without hard coal, I’ll believe they was a Greece or Rome, but not befur.” — Dunne, Finley Peter, OBSERVATIONS BY MR. DOOLEY, New York, 1902 “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Roman Catholicism HDT WHAT? INDEX ROMAN CATHOLICISM CATHOLICISM 312 CE October 28: Our favorite pushy people, the Romans, met at Augusta Taurinorum in northern Italy some even pushier people, to wit the legions of Constantine the Great — and the outcome of this would be an entirely new Pax Romana. While about to do battle against the legions of Maxentius which outnumbered his own 4 to 1, Constantine had a vision in which he saw a compound symbol (chi and rho , the beginning of ) appearing in the cloudy heavens,1 and heard “Under this sign you will be victorious.” He placed the symbol on his helmet and on the shields of his soldiers, and Maxentius’s horse threw him into the water at Milvan (Mulvian) Bridge and the Roman commander was drowned (what more could one ask God for?). 1. In a timeframe in which no real distinction was being made between astrology and astronomy, you will note, seeing a sign like this in the heavens may be classed as astronomy quite as readily as it may be classed as astrology. -

The Day of Judaism in the Catholic Church of Poland

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs) Spring 5-18-2015 The aD y of Judaism in the Catholic Church of Poland Piotr Dudek Seton Hall University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Dudek, Piotr, "The aD y of Judaism in the Catholic Church of Poland" (2015). Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs). 2098. https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/2098 The Day of Judaism in the Catholic Church of Poland by Piotr Dudek Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Department of Religion Seton Hall University May 2015 © 2015 Piotr Dudek 2 SETON HALL UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION APPROVAL FOR SUCCESSFUL DEFENSE Master’s Candidate, Piotr Dudek , has successfully defended and made the required modifications to the text of the master’s thesis for the M.A. during this Spring Semester 2015 . DISSERTATION COMMITTEE (please sign and date beside you name) The mentor and any other committee members who wish to review revisions will sign and date this document only when revisions have been completed. Please return this form to the Office of Graduate Studies, where it will be placed in the candidate’s file and submit a copy with your final diss ertation. 3 Abstract: The Day of Judaism in the Catholic Church of Poland This master’s thesis discusses “The Day of Judaism in the Catholic Church of Poland,” a special time in the Polish Church calendar to rediscover her roots in Judaism. -

Evangelicals, Jews, and Anti-Catholicism in Britain, C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE 10.14324/111.444.jhs.2016v47.009 provided by Birkbeck Institutional Research Online Evangelicals, Jews, and anti-Catholicism in Britain, c. 1840–1900 david feldman Jews in the nineteenth century became entangled in a series of affairs. The term “affair” did not connote merely an injustice but the process through which a perceived wrong became the object of mobilized public opinion. Most famously, for the Jews, there were the Damascus, Mortara, and Dreyfus affairs. All three placed Jews in conflict with the Catholic Church. The emergence of these affairs was one facet of a new political culture constituted by the reformed franchise, by petitions, public meetings, and a press which together constituted “public opinion”.1 Evangelical Protestants offered Jews support in these struggles. The nature of this support has become the subject of growing but divergent interest among scholars. Nadia Valman has explored the figure of “the Jew” in the evangelical imagination. She highlights the gendered ambivalence of evangelical representations of “the Jew”. She draws attention to the repeated iteration of the dual images of the “good” (spiritual and feeling) Jewess and the “bad” (materialistic and legalistic) Jew.2 In contrast to this approach, which points to an irreducible ambivalence in evangelical attitudes, recent books by Donald Lewis and by Hilary and William Rubinstein, reach unreservedly positive conclusions. Lewis deprecates what he sees as “an article of faith” among scholars “that the professed love of Jews by Christians is in some way a form of antisemitism, in spite of all evidence to the contrary.” The Rubinsteins highlight what they regard as a powerful and neglected tradition of Christian philosemitism.3 The 1 Miles Taylor, “John Bull and the Iconography of Public Opinion in England c. -

Benedict XVI and the Interpretation of Vatican II

Cr St 28 (2007) 323-337 Benedict XVI and the Interpretation of Vatican II As the fortieth anniversary of the close of the Second Vatican Council approached, rumors began to spread that Pope Benedict XVI would use the occasion to address the question of the interpretation of the Council. The rumor was particularly promoted by Sandro Ma- gister, columnist of L’Espresso and author of a widely read weekly newsletter on the Internet. For some time Magister had used this newsletter to criticize the five-volume History of Vatican II that had been published under the general editorship of Giuseppe Alberigo. When the last volume of this History appeared, Magister’s newsletter called it a «non-neutral history» (9 Nov. 2001). The role of Giuseppe Dossetti at the Council and the reform-proposals of the Istituto per le Scienze Religiose that he founded were the objects of three separate newsletters (1 Dec. 2003; 3 Jan 2005; 30 Aug. 2005). In a web-article on 22 June 2005, under the title: «Vatican II: The True History Not Yet Told», Magister gave great prominence to the launching of a book presented as a «counterweight» to the Alberigo History. For several years, its author, Agostino Marchetto, had been publishing severely critical reviews of the successive volumes of that History and of several auxiliary volumes generated in the course of the project sponsored by the Bologna Institute. Marchetto had now assembled these review-essays into a large volume entitled Il Conci- lio Ecumenico Vaticano II: Contrappunto per la sua storia and pub- lished by the Vatican Press.1 Magister’s account of the launch of the book gave a good deal of attention to an address by the head of the Italian Bishops’ Confer- 1 A. -

Glossary, Evaluations, Resources, and Bibliography. C/JEEP

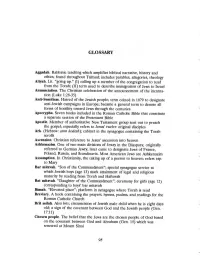

GLOSSARY Aggadah. Rabbinic teaching which amplifies biblical narrative, history and ethics; found throughout Talmud; includes parables, allegories, theology Aliyah. Lit. "going up." (I) calling up a member of the congregation to read from the Torah; (II) term used to describe immigration of Jews to Israel Annunciation. The Christian celebration of the announcement of the incarna- tion (Luke 1:28-35) Anti-Semitism. Hatred of the Jewish people; term coined in 1879 to designate anti-Jewish campaigns in Europe; became a general term to denote all forms of hostility toward Jews through the centuries Apocrypha. Seven books included in the Roman Catholic Bible that constitute a separate section of the Protestant Bible Apostle. Member of authoritative New Testament group sent out to preach the gospel; especially refers to Jesus' twelve original disciples Ark. (Hebrew: awn kodesh); cabinet in the synagogue containing the Torah scrolls Ascension. Christian reference to Jesus' ascension into heaven Ashkenazim. One of two main divisions of Jewry in the Diaspora; originally referred to German Jewry, later came to designate Jews of France, Poland, Russia, and Scandinavia. Most American Jews are Ashkenazim Assumption. In Christianity, the taking up of a person to heaven; refers esp. to Mary Bar mitzvah. "Son of the Commandment"; special synagogue service at which Jewish boys (age 13) mark attainment of legal and religious maturity by reading from Torah and Haftorah Bat mitzvah. "Daughter of the Commandment"; ceremony for girls (age 12) corresponding to boys' bar mitzvah Bimah. "Elevated place"; platform in synagogue where Torah is read Breviary. A book containing the prayers, hymns, psalms, and readings for the Roman Catholic Church Brit milah. -

Confronting Anti-Semitism in Catholic Theology After the Holocaust Carolyn Wesnousky Connecticut College, [email protected]

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College History Honors Papers History Department 2012 “Under the Very Windows of the Pope”: Confronting Anti-Semitism in Catholic Theology after the Holocaust Carolyn Wesnousky Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/histhp Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Wesnousky, Carolyn, "“Under the Very Windows of the Pope”: Confronting Anti-Semitism in Catholic Theology after the Holocaust" (2012). History Honors Papers. 15. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/histhp/15 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the History Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. “Under the Very Windows of the Pope”: Confronting Anti-Semitism in Catholic Theology after the Holocaust An Honors Thesis Presented by Carolyn Wesnousky To The Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major Field Connecticut College New London, Connecticut April 26, 2012 1 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………...…………..4 Chapter 1: Living in a Christian World......…………………….….……….15 Chapter 2: The Holocaust Comes to Rome…………………...…………….49 Chapter 3: Preparing the Ground for Change………………….…………...68 Chapter 4: Nostra Aetate before the Second Vatican Council……………..95 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………110 Appendix……………………………………………..……………………114 Bibliography………………………………………………………………..117 2 Acknowledgements As much as I would like to claim sole credit for the effort that went into creating this paper, I need to take a moment and thank the people without whom I never would have seen its creation. -

The Mortara Affair and the Question of Thomas Aquinas's Teaching

SCJR 14, no. 1 (2019): 1-18 The Mortara Affair and the Question of Thomas Aquinas’s Teaching Against Forced Baptism MATTHEW TAPIE [email protected] Saint Leo University, Saint Leo, FL 33574 Introduction In January 2018, controversy over the Mortara affair remerged in the United States with the publication of Dominican theologian Romanus Cessario’s essay de- fending Pius IX’s decision to remove Edgardo Mortara, from his home, in Bologna.1 In order to forestall anti-Catholic sentiment in reaction to an upcoming film, Cessario argued that the separation of Edgardo from his Jewish parents is what the current Code of Canon Law, and Thomas Aquinas’s theology of baptism, required.2 For some, the essay damaged Catholic-Jewish relations. Writing in the Jewish Review of Books, the Archbishop of Philadelphia, Charles Chaput, lamented that Cessario’s defense of Pius revived a controversy that has “left a stain on Catholic- Jewish relations for 150 years.” “The Church,” wrote Chaput, “has worked hard for more than 60 years to heal such wounds and repent of past intolerance toward the Jewish community. This did damage to an already difficult effort.”3 In the 1 On June 23rd, 1858, Pope Pius IX ordered police of the Papal States to remove a six-year-old Jewish boy, Edgardo Mortara, from his home, in Bologna, because he had been secretly baptized by his Chris- tian housekeeper after allegedly falling ill. Since the law of the Papal States stipulated that a person baptized must be raised Catholic, Inquisition authorities forcibly removed Edgardo from his parents’ home, and transported him to Rome. -

Dignitatis Humanae and the Development of Moral Doctrine: Assessing Change in Catholic Social Teaching on Religious Liberty

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Dignitatis humanae and the Development of Moral Doctrine: Assessing Change in Catholic Social Teaching on Religious Liberty A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Religious Studies Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By Barrett Hamilton Turner Washington, D.C 2015 Dignitatis humanae and the Development of Moral Doctrine: Assessing Change in Catholic Social Teaching on Religious Liberty Barrett Hamilton Turner, Ph.D. Director: Joseph E. Capizzi, Ph.D. Vatican II’s Declaration on Religious Liberty, Dignitatis humanae (DH), poses the problem of development in Catholic moral and social doctrine. This problem is threefold, consisting in properly understanding the meaning of pre-conciliar magisterial teaching on religious liberty, the meaning of DH itself, and the Declaration’s implications for how social doctrine develops. A survey of recent scholarship reveals that scholars attend to the first two elements in contradictory ways, and that their accounts of doctrinal development are vague. The dissertation then proceeds to the threefold problematic. Chapter two outlines the general parameters of doctrinal development. The third chapter gives an interpretation of the pre- conciliar teaching from Pius IX to John XXIII. To better determine the meaning of DH, the fourth chapter examines the Declaration’s drafts and the official explanatory speeches (relationes) contained in Vatican II’s Acta synodalia. The fifth chapter discusses how experience may contribute to doctrinal development and proposes an explanation for how the doctrine on religious liberty changed, drawing upon the work of Jacques Maritain and Basile Valuet. -

1 Beginning the Conversation

NOTES 1 Beginning the Conversation 1. Jacob Katz, Exclusiveness and Tolerance: Jewish-Gentile Relations in Medieval and Modern Times (New York: Schocken, 1969). 2. John Micklethwait, “In God’s Name: A Special Report on Religion and Public Life,” The Economist, London November 3–9, 2007. 3. Mark Lila, “Earthly Powers,” NYT, April 2, 2006. 4. When we mention the clash of civilizations, we think of either the Spengler battle, or a more benign interplay between cultures in individual lives. For the Spengler battle, see Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996). For a more benign interplay in individual lives, see Thomas L. Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1999). 5. Micklethwait, “In God’s Name.” 6. Robert Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). “Interview with Robert Wuthnow” Religion and Ethics Newsweekly April 26, 2002. Episode no. 534 http://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/week534/ rwuthnow.html 7. Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity, 291. 8. Eric Sharpe, “Dialogue,” in Mircea Eliade and Charles J. Adams, The Encyclopedia of Religion, first edition, volume 4 (New York: Macmillan, 1987), 345–8. 9. Archbishop Michael L. Fitzgerald and John Borelli, Interfaith Dialogue: A Catholic View (London: SPCK, 2006). 10. Lily Edelman, Face to Face: A Primer in Dialogue (Washington, DC: B’nai B’rith, Adult Jewish Education, 1967). 11. Ben Zion Bokser, Judaism and the Christian Predicament (New York: Knopf, 1967), 5, 11. 12. Ibid., 375. -

Stories of Fourth Amendment Disrespect: from Elian to the Internment

Fordham Law Review Volume 70 Issue 6 Article 18 2002 Stories of Fourth Amendment Disrespect: From Elian to the Internment Andrew E. Taslitz Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Andrew E. Taslitz, Stories of Fourth Amendment Disrespect: From Elian to the Internment, 70 Fordham L. Rev. 2257 (2002). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol70/iss6/18 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stories of Fourth Amendment Disrespect: From Elian to the Internment Cover Page Footnote Visiting Professor, Duke University Law School, 2000-01; Professor of Law, Howard University School of Law; J.D., University of Pennsylvania School of Law, 1981, former Assistant District Attorney, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. I thank my wife, Patricia V. Sun, Esq., Professors Robert Mosteller, Sara Sun-Beale, Girardeau Spann, joseph Kennedy, Eric Muller, Ronald Wright, and many other members of the Triangle Criminal Law Working Group, for their comments on early drafts of this Article. I also thank my research assistants, Nicole Crawford, Eli Mazur, and Amy Pope, and my secretary, Ann McCloskey. Appreciation also goes to the Howard University School of Law for funding this project, and to the Duke University Law School for helping me see this effort through to its completion. -

Vatican II and the Calvary of the Church

Vatican II and the Calvary of the Church Editor’s Note: The interventions of Archbishop Viganò and Bishop Schneider have certainly ignited a debate about what the Church should do regarding the problem of Vatican II. Catholic Family News was honored to be asked to publish the English translation of a new intervention on this topic (originally published in Italian here) by Fr. Serafino Maria Lanzetta, a former member of the Franciscan Friars of the Immaculate who is now the Superior of a new community called the Family of Mary Immaculate and St. Francis (established in the Diocese of Portsmouth, England). Father discusses the failure of the “hermeneutic of continuity” offered by Benedict XVI as a solution to the crisis. Benedict’s proposal has always been seen as an ineffective remedy by CFN, but now new voices of critique are being raised around the globe. Archbishop Viganò has declared that it “shipwrecked miserably” and differing proposals to resolve this problem have been brought forward. Fr. Lanzetta provides a helpful explanation and critique of the proposals of Cardinal Brandmüller, Archbishop Viganò, and Bishop Schneider. We at CFN welcome this long-overdue debate and will continue to use our website and monthly paper to promote it and continue the discussion. — Brian M. McCall, Editor-in-Chief ***** Vatican II and the Calvary of the Church By Fr. Serafino M. Lanzetta Recently, the debate about the correct interpretation of the Second Vatican Council has been rekindled. It is true that every council has interpretative problems and very often opens new ones rather than resolving the ones that preceded it. -

Elkin, Judith Laikin. "Jews and Non-Jews. " the Jews of Latin America. Rev. Ed. New York

THE JEWS OF LATIN AMERICA Revised Edition JUDITH LAIKIN ELKIN HOLMES & MEIER NEW YORK / LONDON Published in the United Stutes of America 1998 b y ll olmes & Meier Publishers. Inc . 160 Broadway ew York, NY 10038 Copyr ight © 199 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, 1.nc. F'irst edition published und er th e title Jeics of the u1tl11A111erica11 lle1'11hlics copyright © 1980 The University of o rth Ca rolina Press . Chapel Hill , NC . All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any elec troni c o r mechanical means now known or to be invented, including photocopying , r co rdin g, and information storage and retrieval systems , without permission in writing from the publishers , exc·ept by a reviewe r who may quote brief passages in a review. The auth or acknow ledges with gra titud e the court esy of the American Jewish lli stori cal Society to reprint the follo,ving articl e which is published in somewhat different form in this book: "Goo dnight , Sweet Gaucho: A Revisio nist View of the Jewis h Agricultural Experiment in Argentina, " A111eric1111j etds h Historic(I/ Q11111terly67 (March 1978 ): 208 - 23. Most of the photographs in this boo k were includ d in the exhibit ion . "Voyages to F're dam: .500 Years of Je,vish Li~ in Latin America and the Caribbean ," and were ma de availab le throu ,I, the court esy of the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith . Th e two photographs of the AMIA on pages 266 - 267 we re s uppli ed by the AMIA -Co munidad Judfa de Buenos Aires.