Latin America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Redalyc.Recepção Lusófona De Hermann Broch – Período 1959-2015

Pandaemonium Germanicum. Revista de Estudos Germanísticos E-ISSN: 1982-8837 [email protected] Universidade de São Paulo Brasil Bonomo, Daniel Recepção lusófona de Hermann Broch – Período 1959-2015 Pandaemonium Germanicum. Revista de Estudos Germanísticos, vol. 19, núm. 28, septiembre-octubre, 2016, pp. 1-19 Universidade de São Paulo São Paulo, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=386646680001 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto 1 Bonomo, D. - Recepção lusófona de Broch Recepção lusófona de Hermann Broch – Período 1959-2015 [Hermann Broch’s reception in Brazil and Portugal between 1959 and 2015] http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/1982-88371928119 Daniel Bonomo1 Abstract: The response, in Brazil and Portugal, to recently published editions of the novels The Sleepwalkers and The Death of Vergil by Hermann Broch shows a growing interest in, or perhaps a rather late response to, the author. One might wonder what events have been shaping the history of his literary presence in the Portuguese speaking world. This paper takes an unprecedented look at how Broch’s fictional and theoretical works have been received, in Portuguese, from the 1950s to the present day and provides a framework of main events – inclusions in the literary historiography, translations, theoretical and artistic utilizations. The objective is to expand the map of Broch’s readings and to offer references which might promote further discussions and advance the research on the author and his work. -

The Day of Judaism in the Catholic Church of Poland

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs) Spring 5-18-2015 The aD y of Judaism in the Catholic Church of Poland Piotr Dudek Seton Hall University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Dudek, Piotr, "The aD y of Judaism in the Catholic Church of Poland" (2015). Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs). 2098. https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/2098 The Day of Judaism in the Catholic Church of Poland by Piotr Dudek Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Department of Religion Seton Hall University May 2015 © 2015 Piotr Dudek 2 SETON HALL UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION APPROVAL FOR SUCCESSFUL DEFENSE Master’s Candidate, Piotr Dudek , has successfully defended and made the required modifications to the text of the master’s thesis for the M.A. during this Spring Semester 2015 . DISSERTATION COMMITTEE (please sign and date beside you name) The mentor and any other committee members who wish to review revisions will sign and date this document only when revisions have been completed. Please return this form to the Office of Graduate Studies, where it will be placed in the candidate’s file and submit a copy with your final diss ertation. 3 Abstract: The Day of Judaism in the Catholic Church of Poland This master’s thesis discusses “The Day of Judaism in the Catholic Church of Poland,” a special time in the Polish Church calendar to rediscover her roots in Judaism. -

O Que Não Pôde Ser Dito 145 OTTO MARIA CARPEAUX

COLFFIELD, Carol. Otto Maria Carpeaux: O Que Não Pôde Ser Dito OTTO MARIA CARPEAUX: O QUE NÃO PÔDE SER DITO OTTO MARIA CARPEAUX: WHAT COULD NOT HAVE BEEN SAID Carol Colffield Resumo Reconstituir vidas na forma escrita é também navegar sobre os silêncios de seus protagonistas. Neste ensaio, que é parte de um universo de estudo maior focado nos intelectuais judeus perseguidos pelo nazifascismo e refugiados no Brasil, enveredamos pelos silêncios de um desses personagens, Otto Maria Carpeaux (Viena, 1908 – Rio de Janeiro, 1978) e pelas descobertas que resultaram da análise de documentos obtidos em arquivos na Áustria e em Israel, os quais revelam aspectos até então não registrados pela historiografia no que se refere tanto às origens do autor quanto ao seu passado de perseguições na Europa. Além do interesse intrínseco à própria trajetória de Carpeaux, tais descobertas confirmam que, em seu caso, o exílio não significou o fim da violência. Palavras-chave: Otto Maria Carpeaux, Otto Maria Karpfen, Carpeaux, Intelectuais Judeus, Refugiados Judeus. Abstract To reconstitute lives in written form is also to navigate the silences of the protagonists. In this essay, which is part of a larger universe of study focused on Jewish intellectuals who were persecuted by Nazism and took refuge in Brazil, we turn to the silence of one of those Doutoranda do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos Judaicos e Árabes (FFLCH-USP). Pesquisadora do Arqshoah-LEER-USP e bolsista do Projeto Vozes do Holocausto, ambos coordenados pela Profa. Dra. Maria Luiza Tucci Carneiro. 145 Cad. Líng. Lit. Hebr., n. 15, p. 145-154, 2017 characters, Otto Maria Carpeaux (Viena, 1908 – Rio de Janeiro, 1978), and to the discoveries that resulted from the analysis of documents obtained from archives in Austria and Israel, which reveal aspects not recorded by the historiography with regard both to the author’s origins and to his past of persecutions in Europe. -

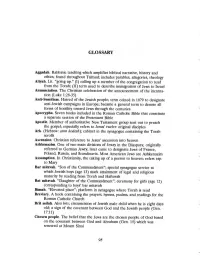

Glossary, Evaluations, Resources, and Bibliography. C/JEEP

GLOSSARY Aggadah. Rabbinic teaching which amplifies biblical narrative, history and ethics; found throughout Talmud; includes parables, allegories, theology Aliyah. Lit. "going up." (I) calling up a member of the congregation to read from the Torah; (II) term used to describe immigration of Jews to Israel Annunciation. The Christian celebration of the announcement of the incarna- tion (Luke 1:28-35) Anti-Semitism. Hatred of the Jewish people; term coined in 1879 to designate anti-Jewish campaigns in Europe; became a general term to denote all forms of hostility toward Jews through the centuries Apocrypha. Seven books included in the Roman Catholic Bible that constitute a separate section of the Protestant Bible Apostle. Member of authoritative New Testament group sent out to preach the gospel; especially refers to Jesus' twelve original disciples Ark. (Hebrew: awn kodesh); cabinet in the synagogue containing the Torah scrolls Ascension. Christian reference to Jesus' ascension into heaven Ashkenazim. One of two main divisions of Jewry in the Diaspora; originally referred to German Jewry, later came to designate Jews of France, Poland, Russia, and Scandinavia. Most American Jews are Ashkenazim Assumption. In Christianity, the taking up of a person to heaven; refers esp. to Mary Bar mitzvah. "Son of the Commandment"; special synagogue service at which Jewish boys (age 13) mark attainment of legal and religious maturity by reading from Torah and Haftorah Bat mitzvah. "Daughter of the Commandment"; ceremony for girls (age 12) corresponding to boys' bar mitzvah Bimah. "Elevated place"; platform in synagogue where Torah is read Breviary. A book containing the prayers, hymns, psalms, and readings for the Roman Catholic Church Brit milah. -

1 Beginning the Conversation

NOTES 1 Beginning the Conversation 1. Jacob Katz, Exclusiveness and Tolerance: Jewish-Gentile Relations in Medieval and Modern Times (New York: Schocken, 1969). 2. John Micklethwait, “In God’s Name: A Special Report on Religion and Public Life,” The Economist, London November 3–9, 2007. 3. Mark Lila, “Earthly Powers,” NYT, April 2, 2006. 4. When we mention the clash of civilizations, we think of either the Spengler battle, or a more benign interplay between cultures in individual lives. For the Spengler battle, see Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996). For a more benign interplay in individual lives, see Thomas L. Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1999). 5. Micklethwait, “In God’s Name.” 6. Robert Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). “Interview with Robert Wuthnow” Religion and Ethics Newsweekly April 26, 2002. Episode no. 534 http://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/week534/ rwuthnow.html 7. Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity, 291. 8. Eric Sharpe, “Dialogue,” in Mircea Eliade and Charles J. Adams, The Encyclopedia of Religion, first edition, volume 4 (New York: Macmillan, 1987), 345–8. 9. Archbishop Michael L. Fitzgerald and John Borelli, Interfaith Dialogue: A Catholic View (London: SPCK, 2006). 10. Lily Edelman, Face to Face: A Primer in Dialogue (Washington, DC: B’nai B’rith, Adult Jewish Education, 1967). 11. Ben Zion Bokser, Judaism and the Christian Predicament (New York: Knopf, 1967), 5, 11. 12. Ibid., 375. -

Forschungsprojekt Brasilianische Intellektuelle

Alemania-Brasil: dinámicas transculturales y ensayos transdisciplinarios. Otto María Carpeaux, la superación del exilio por la transculturación * Ligia Chiappini** Resumen El texto trata de Otto María Carpeaux, en el contexto de un proyecto más amplio sobre ensayistas brasileños y europeos, que tuvieron una relación importante de vida y trabajo con la cultura de lengua alemana o con la propia Alemania. El ensayo, género fundamental en Brasil y en toda América Latina, está en el corazón de ese proyecto. Para Carpeaux, como para Anatol Rosenfeld, el exilio fue el origen de una nueva vida personal y profesional, construida en Brasil. Ambos pertenecen a la generación de intelectuales de lengua alemana que, huyendo del Nacionalsocialismo, quedaron en América, en este caso, en Brasil, que era todavía un país subdesarrollado. Ellos aprendieron el portugués y muchas otras cosas en muy poco tiempo, no apenas para conseguir sobrevivir, sino también para conseguir vivir y trabajar plenamente. De cierto modo, tuvieron que morir un poco para renacer, simultáneamente iguales y diferentes. Palabras clave Carpeaux; ensayo; nazismo; exilio; literatura brasileña. Abstract This paper deals with Otto Maria Carpeaux in the context of a wider project on European and Brazilian essayists who had an important relationship to the culture of the German language or to Germany itself in their lives and work. The essay, a fundamental genre for Brazil and all of Latin America, is at the heart of this project. For Carpeaux, as for Anatol Rosenfeld, exile was the origin of the new life and work that they constructed in Brazil. Both belonged to the generation of intellectuals of the German language who, fleeing from National Socialism, would stay in America, that is, in Brazil in their cases, which was then still an underdeveloped country. -

Elkin, Judith Laikin. "Jews and Non-Jews. " the Jews of Latin America. Rev. Ed. New York

THE JEWS OF LATIN AMERICA Revised Edition JUDITH LAIKIN ELKIN HOLMES & MEIER NEW YORK / LONDON Published in the United Stutes of America 1998 b y ll olmes & Meier Publishers. Inc . 160 Broadway ew York, NY 10038 Copyr ight © 199 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, 1.nc. F'irst edition published und er th e title Jeics of the u1tl11A111erica11 lle1'11hlics copyright © 1980 The University of o rth Ca rolina Press . Chapel Hill , NC . All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any elec troni c o r mechanical means now known or to be invented, including photocopying , r co rdin g, and information storage and retrieval systems , without permission in writing from the publishers , exc·ept by a reviewe r who may quote brief passages in a review. The auth or acknow ledges with gra titud e the court esy of the American Jewish lli stori cal Society to reprint the follo,ving articl e which is published in somewhat different form in this book: "Goo dnight , Sweet Gaucho: A Revisio nist View of the Jewis h Agricultural Experiment in Argentina, " A111eric1111j etds h Historic(I/ Q11111terly67 (March 1978 ): 208 - 23. Most of the photographs in this boo k were includ d in the exhibit ion . "Voyages to F're dam: .500 Years of Je,vish Li~ in Latin America and the Caribbean ," and were ma de availab le throu ,I, the court esy of the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith . Th e two photographs of the AMIA on pages 266 - 267 we re s uppli ed by the AMIA -Co munidad Judfa de Buenos Aires. -

Os Escritos De Otto Maria Carpeaux Sobre Música Erudita1

VÍNCULOS TEÓRICOS E SONOROS: OS ESCRITOS DE OTTO MARIA CARPEAUX SOBRE MÚSICA ERUDITA1 THEORETICAL AND SOUND CONNECTIONS: THE OTTO MARIA CARPEAUX’S ESSAYS ABOUT CLASSIC MUSIC Mauro Souza Ventura2 Resumo Entre os anos de 1931 e 1934 o jornalista e crítico literário austríaco-brasileiro Otto Maria Carpeaux (1900-1978) publicou uma série de artigos sobre música na revista Signale für die Musikalische Welt, de Berlim. Esses artigos são parte de um conjunto maior de textos, que abordam temas como política, sociedade, cultura e religião. Todos foram escritos e publicados em periódicos da Áustria e da Alemanha, antes de sua vinda para o Brasil, em 1939. Neste relato, apresentamos os resultados parciais de uma pesquisa work in progress e cujos procedimentos metodológicos iniciam com uma abordagem de cunho histórico-social. Em seguida, os escritos sobre música de Otto Maria Carpeaux são estudados a partir dos vínculos entre a paisagem sonora presente na cultura musical vienense do fin-du-siècle e do início do século 20 e os marcos teóricos que informam a cultura do ouvir. (Menezes, 2012; 2016). Assim, interessa-nos identificar e descrever os enlaces possíveis entre essa escola do ouvir chamada Viena e a cosmovisão que surge dos escritos sobre música de Otto Maria Carpeaux. Como conclusão, propomos a hipótese de que a cultura musical vienense da Ringstrasse possibilitou a criação de um ambiente cultural-comunicacional que promoveu a eclosão de trocas simbólicas e de vínculos sonoros que se impregnaram por todos os aspectos da vida social naquele período. Palavras-chave: Cultura do ouvir. Vínculos sonoros; Viena fin-du-siècle. -

Ensaios Reunidos: As Contribuições De Otto Maria Carpeaux Para a Crítica Literária E O Jornalismo Cultural

MEMENTO - Revista de Linguagem, Cultura e Discurso Mestrado em Letras - UNINCOR - ISSN 1807-9717 V. 06, N. 2 (julho-dezembro de 2015) ENSAIOS REUNIDOS: AS CONTRIBUIÇÕES DE OTTO MARIA CARPEAUX PARA A CRÍTICA LITERÁRIA E O JORNALISMO CULTURAL Laio Monteiro Brandão1 Joelma Santana Siqueira2 RESUMO: Nas últimas décadas, a crítica literária jornalística vem encontrando alguns impasses, principalmente em relação à velocidade do mercado editorial e da informação, em detrimento do espaço físico cada vez menor, impedindo a possibilidade de aprofundamento nos temas abordados. A partir do debate sobre as funções, características e dificuldades da atividade crítica, o presente artigo busca apresentar algumas sugestões sobre as áreas do jornalismo crítico, jornalismo cultural e crítica literária baseado nas contribuições feitas por Otto Maria Carpeaux ao longo de sua atividade como crítico, historiador da literatura e jornalista. Sendo assim, buscar-se-á destacar as características fundamentais de Carpeaux em função de seu método a partir da obra Ensaios Reunidos. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Otto Maria Carpeaux; Jornalismo Crítico; Crítica Literária; Literatura Comparada. ABSTRACT: In recent decades, the journalistic literary criticism has found some dead ends, especially for the speed of publishing and information, to the detriment of the over and over small physical space, hindering the possibility of to get deep into the discussed topics. From the debate about the functions, characteristics and difficulties of the criticism activity, the current article intends to introduce some suggestions upon the critical and cultural journalism and the literary criticism based on the contributions done by Otto Maria Carpeaux along his activity as a critic, literature historian and journalist. -

Jews and Christians, Fellow Travelers to the End of Days (Daniel 12)

Jew s and C hristians, Fellow T ravelers to the E nd of D ays JEWS AND CHRISTIANS UNITED FOR ISRAEL provides both Jews and Christians with an association through which, together, they can show their support for Israel and stand Jews and Christians, united against all forms of theological, cultural and political anti-Semitism. Anti-Semitism is an assault on God, as well as on the Jewish people. Fellow Travelers to Come let us go up to the Mountain of the Lord, to the Temple of the God of Jacob, and He will teach us of His Ways and we will walk in the End of Days His paths. For from Zion will the Torah come forth, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem. (Isaiah 2:3) Martin M. van Brauman, the president of Jews and Christians United For Israel, Inc., is also the Corporate Secretary, Treasurer, Senior Vice President and Director of Zion Oil & Gas, Inc. He is the managing director of e Abraham Foundation (Geneva, Switzerland) and the Bnei Joseph Foundation (Israeli Amuta). He is a Texas board member of the Bnai Zion Foundation, an Advisory Board Member on the Jewish and Israel Studies Program at the University of North Texas and an AIPAC B Capitol Club member. www.jewsandchristiansunitedforisrael.org M M. B JEWS AND CHRISTIANS, FELLOW TRAVELERS TO THE END OF DAYS (DANIEL 12) MARTIN M. VAN BRAUMAN Copyright © 2011 by Martin M. Van Brauman Second Edition 2020 Published in The United States of America by JEWS AND CHRISTIANS UNITED FOR ISRAEL, INC. 12655 North Central Expressway, Suite 1030 Dallas, Texas 75243 www.JewsandChristiansunitedforIsrael.org All rights reserved. -

Censoring the Prophetic How Constantinian and Progressive Jews Censor Debate About the Future of the Jewish and Palestinian People Marc H

Censoring the Prophetic How Constantinian and Progressive Jews Censor Debate about the Future of the Jewish and Palestinian People Marc H. Ellis Marc H. Ellis is University Professor of Jewish Studies and Professor of History at Baylor University. He also directs the university’s Center for Jewish Studies. He is a board members of the Society of Jewish Ethics and a steering committee member of the Ethics Section of the American Academy of Religion. Ellis is the author of Judaism Does Not Equal Israel (New Press, 2009) and Toward a Jewish Theology of Liberation (Baylor University Press, 2004). In the mid 1980s I first encountered attempts to censor my thoughts on the question of Israel and Palestine. I was teaching at Maryknoll, the Catholic mission-sending society and the English language publisher of liberation theology. Though liberation theology mostly emanates from the third world and is primarily Christian, at the time I was also writing a Jewish theology of liberation.[1] I came to Maryknoll in 1980 where I was asked to found and direct a master’s program in Justice and Peace Studies. Each year we had an extensive and exciting month-long summer program that attracted activists, intellectuals, and missionaries from around the world. The program included courses and workshops that focused on foundational issues of justice and peace. Over the years we discussed the global economic system, apartheid South Africa, feminist struggles in a global perspective, and the tension between nonviolence and armed revolution. Our 1988 summer session was dedicated to the Peruvian father of liberation theology, Gustavo Gutierrez. -

Avant-Gardism and Latinity

Diversité et Identité Culturelle en Europe AVANT-GARDISM AND LATINITY Petre Gheorghe BÂRLEA „Ovidius” University Constanța [email protected] Abstract: The effects the Avant-garde had on the way of thinking of people belonging to various cultures and professions were bigger than expected. The fact that there were Dada promoters who belonged to nations of Latin origin, such as Tr. Tzara and G. M. Teles, led future theoreticians to advocate the idea of a Latin union which - through joint cultural actions - could change the entire political, economic, and spiritual life. Keywords: Avant-garde, Latinity, Latin union, economic progress, cultural reforms. The Dada extravagances and its permanent denial of any social conventions were expected to cause the rapid disintegration of an art movement whose central figures claimed they simply did not believe in progress. Nevertheless, according to the world history of this art movement1, their ideas decisively contributed to progress within some cultures that had never before experimented innovations in art. It is a fact that the ending signs of the Dada movement appeared just four years after its debut2, in spring 1920, when The First International Dada Fair, organized in Berlin, ended in a law suit which scattered its participants3. The misunderstandings continued later in Paris, although a 1This very fact, i.e. „the rapid international expansion”, was one of the characteristic features of the Avant-garde. 2Literary historians registered the debut of the Dada movement in Zürich, on February 2, 1916, cf. Marc Dachy, Archives dada – Chroniques, Éditions Hazan, Paris 2005, p. 20. 3 Roselee Goldberg, 2001, chapter 3.