Cantonese Sin 先 and the Question of Microvariation and Macrovariation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wu and Shaman Author(S): Gilles Boileau Source: Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol

Wu and Shaman Author(s): Gilles Boileau Source: Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Vol. 65, No. 2 (2002), pp. 350-378 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of School of Oriental and African Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4145619 Accessed: 08/12/2009 22:46 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=cup. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. School of Oriental and African Studies and Cambridge University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

The Emergence of Labour Camps in Shandong Province, 1942-1950 Author(S): Frank Dikötter Source: the China Quarterly, No

The Emergence of Labour Camps in Shandong Province, 1942-1950 Author(s): Frank Dikötter Source: The China Quarterly, No. 175 (Sep., 2003), pp. 803-817 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20059040 Accessed: 27/02/2009 19:32 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=cup. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press and School of Oriental and African Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The China Quarterly. -

Education Employment Publications

Tian CV 1 Xiaofei Tian Dept. of East Asian Languages and Civilizations Harvard University 2 Divinity Ave., Cambridge, MA 02138, USA http://scholar.harvard.edu/xtian/ Education PhD, Harvard University, 1998 MA, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 1991 BA, Beijing University, 1989 Employment 2006-present Professor of Chinese Literature, Harvard University 2005-2006 Associate Professor of Chinese Literature, Harvard University 2000-2005 Preceptor in Chinese, Harvard University 1999-2000 Assistant Professor of Chinese Literature, Cornell University 1998-1999 Visiting Assistant Professor of Chinese Literature, Colgate University Publications Books in English • The Halberd at Red Cliff: Jian’an and the Three Kingdoms. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2018. • The World of a Tiny Insect: A Memoir of the Taiping Rebellion and Its Aftermath by Zhang Daye. Translated with notes and a critical introduction. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2014. Awarded the inaugural Patrick D. Hanan Book Prize for Translation in 2016. • Visionary Journeys: Travel Writings from Early Medieval and Nineteenth-century China. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2011. Chinese edition: 神遊:中古時代與十九世紀中國行旅文學. Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing, 2015. • Beacon Fire and Shooting Star: The Literary Culture of the Liang (502-557). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2007. Edition in Traditional Chinese: 烽火與流星: 蕭梁文學與文化. Hsinchu: National Tsing Hua University Press, 2009. Edition in Simplified Chinese: Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2010. • Tao Yuanming (365?-427) and Manuscript Culture: The Record of a Dusty Table. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005. Named a Choice Outstanding Academic Title in 2006. o Expanded Chinese edition in Simplified Chinese: 塵几錄: 陶淵明與手抄本 文化研究. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2007. Tian CV 2 Books in Chinese (since 2000) • Empty Spaces 留白: 秋水堂論中西文學 [a collection of essays on literature]. -

Chapter One Introduction Chapter Two the 1920S, People and Weather

Notes Chapter One Introduction 1. Steve Tsang, ed., Government and Politics (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1995); David Faure, ed., Society (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 1997); David Faure and Lee Pui-tak, eds., Economy (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2004); and David Faure, Colonialism and the Hong Kong Mentality (Hong Kong: Centre of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong, 2003). 2. Cindy Yik-yi Chu, The Maryknoll Sisters in Hong Kong, 1921–1969: In Love with the Chinese (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), book jacket. Chapter Two The 1920s, People and Weather 1. R. L. Jarman, ed., Hong Kong Annual Administration Reports 1841–1941, Archive ed., Vol. 4: 1920–1930 (Farnham Common, 1996), p. 26. 2. Ibid., p. 27. 3. S. G. Davis, Hong Kong in Its Geographical Setting (London: Collins, 1949), p. 215. 4. Vicariatus Apostolicus Hongkong, Prospectus Generalis Operis Missionalis; Status Animarum, Folder 2, Box 10: Reports, Statistics and Related Correspondence (1969), Accumulative and Comparative Statistics (1842–1963), Section I, Hong Kong Catholic Diocesan Archives, Hong Kong. 5. Unless otherwise stated, quotations in this chapter are from Folders 1–5, Box 32 (Kowloon Diaries), Diaries, Maryknoll Mission Archives, Maryknoll, New York. 6. Cindy Yik-yi Chu, The Maryknoll Sisters in Hong Kong, 1921–1969: In Love with the Chinese (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), pp. 21, 28, 48 (Table 3.2). 210 / notes 7. Ibid., p. 163 (Appendix I: Statistics on Maryknoll Sisters Who Were in Hong Kong from 1921 to 2004). 8. Jean-Paul Wiest, Maryknoll in China: A History, 1918–1955 (Armonk: M.E. -

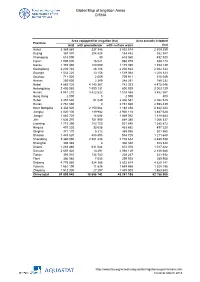

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

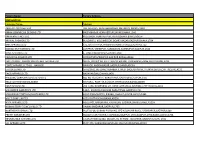

Booklist Email: [email protected] Tel: 020-6258330 Fax: 020-6205794 0821-1

MING YA BOOKS CO. www.mingyabooks.com Booklist Email: [email protected] Tel: 020-6258330 Fax: 020-6205794 0821-1 Cantonese Course Title Author Publisher Page EURO About Hong Kong-Intermediate Cantonese learners (Incl. 1 CD) Hung, Betty/Si C.M. Greenwood Press 106 36,90 Advanced Level Current Cantonese Collo- quialisms (Incl. 1 tape & 1 Audio-CD) Lee, Yin-ping Greenwood Press 140 54,90 Basic Cantonese-A Grammar & Workbook Routledge Grammars Yip, Virginia/Matthews S. Routledge 172 33,80 CantonEase-Practical guide to mastering Cantonese sounds & tones (Incl. 4 CDs) Lee, Yin-ping/Choi Ming-c Greenwood Press 212 79,50 Cantonese book, A Text & cassette-tapes Chan Kwok Kin/Hung B. Greenwood Press NO OR Cantonese Chin.phrase book & dictionary Travel & comm.in cantonese with ease & Berlitz Publishing Co. 224 9,95 Cantonese Colloquial Expressions Lo Tam Fee-yin Chinese University Press 346 39,50 Cantonese Phonetic Dictionary (Chin.Ed.) Xiao Joint Publishing Co. 494 22,60 Cantonese Phrasebook & Dictionary With 2000-word Two-way Dictionary Cheung Chiu-yee/Tao Li Lonely Planet 260 9,99 Cantonese: A comprehensive grammar Matthews, Stephen/Yip V. Routledge 430 48,90 Character Text For Speak Cantonese Book 1 Huang Po-fei/Kok G.P. Far Eastern Publications 298 36,95 Chin-Eng Dictionary-Cantonese in Yale Romanization/Mandarin in Pinyin Man Chik Hon/Ng Lam S.Y. Chinese University Press 522 29,95 Chinese in the marketplace Learn Chinese from advertising Brown, Semmi Greenwood Press 142 32,90 Colloquial Cantonese & Putonghua equiva- lents (with pinyin) Zeng Zifan/Lai S.K.(tr) Joint Publishing Co. -

Names of Chinese People in Singapore

101 Lodz Papers in Pragmatics 7.1 (2011): 101-133 DOI: 10.2478/v10016-011-0005-6 Lee Cher Leng Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore ETHNOGRAPHY OF SINGAPORE CHINESE NAMES: RACE, RELIGION, AND REPRESENTATION Abstract Singapore Chinese is part of the Chinese Diaspora.This research shows how Singapore Chinese names reflect the Chinese naming tradition of surnames and generation names, as well as Straits Chinese influence. The names also reflect the beliefs and religion of Singapore Chinese. More significantly, a change of identity and representation is reflected in the names of earlier settlers and Singapore Chinese today. This paper aims to show the general naming traditions of Chinese in Singapore as well as a change in ideology and trends due to globalization. Keywords Singapore, Chinese, names, identity, beliefs, globalization. 1. Introduction When parents choose a name for a child, the name necessarily reflects their thoughts and aspirations with regards to the child. These thoughts and aspirations are shaped by the historical, social, cultural or spiritual setting of the time and place they are living in whether or not they are aware of them. Thus, the study of names is an important window through which one could view how these parents prefer their children to be perceived by society at large, according to the identities, roles, values, hierarchies or expectations constructed within a social space. Goodenough explains this culturally driven context of names and naming practices: Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore The Shaw Foundation Building, Block AS7, Level 5 5 Arts Link, Singapore 117570 e-mail: [email protected] 102 Lee Cher Leng Ethnography of Singapore Chinese Names: Race, Religion, and Representation Different naming and address customs necessarily select different things about the self for communication and consequent emphasis. -

Transcript of Edited Interview 訪談文字節錄 蕭滋 訪談 Interview with Shaw Tze

香港藝術史研究──第二期 香港藝術館及亞洲藝術文獻庫 合作計劃 Hong Kong Art History Research – Phase II A Collaboration between Hong Kong Museum of Art and Asia Art Archive Transcript of Edited Interview 訪談文字節錄 蕭滋 訪談 Interview with Shaw Tze 訪問員: 李世莊 Interviewer: Jack Lee 2015 年 6 月 9 日 9 June, 2015 香港藝術館 Hong Kong Museum of Art 中資出版機構在 1960 - 1970 年代香港藝術生態中所扮演的角色 The role of mainland-funded publishing organisations in 1960s-1970s Hong Kong’s art ecology Shaw: I was primarily interested in art. But since I joined China International Book Trading Corporation in Beijing, I thought I would stay in publishing forever because the times advocated having a “life-long career” whether it was a life-long revolution or a life-long commitment to publishing. So I never thought about becoming an art practitioner then. I was relocated to Hong Kong from Beijing in 1951. At the time many countries and regions imposed embargo against China, which made it difficult for the bookstore to set stocks from the overseas. So we did it through Hong Kong. When I first arrived in Hong Kong, more of the city’s residents were pro-communist. It was right after mainland China’s liberation, and the nationalists were so corrupted that they were expelled from mainland China. The communists took over the power thanks to their initial integrity. They aspired to good governance. Although they were leftists, they were idealists who fought for national glory. Therefore, I think Hong Kong people at the time were sympathetic to them. This was beneficial to our publishing work. Apart from retail business, Sinminchu Publishing and Joint Publishing were also the general distributors of books published by the mainland, which included a great variety of illustration and picture books. -

Production and Perception of Tones in Cantonese Continuous Speech

Production and Perception of Tones in Cantonese Continuous Speech ,,:二 、 WONGT-¥ing Wai � ”j A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Linguistics •The Chinese University of Hong Kong January 2007 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this thesis. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in the thesis in a proposed publication must seek copyright release from the Dean of the Graduate School. 0 3 M 18 )|| ~UNIVERSITY N^bXjJBRAnY SYSTEMyy^ Thesis/Assessment Committee Prof. Wang Shi Yuan William (Chair) Prof. Lee Hun Tak Thomas (Thesis Supervisor) Prof. Jiang-King Ping (Committee Member) Prof. Zee Yun Yang Eric (External Examiner) ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This thesis topic would not exist without my thesis supervisor, Thomas Lee, who whole-heartedly provided guidance and invaluable advice throughout the whole duration of my research. With his knowledge in linguistics and many related fields, I was able to broaden my horizon of knowing about language from different perspectives. I am also grateful to William Wang and Eric Zee for generously allowing me to join their weekly research seminars. Through collaborative atmosphere from their research groups, I could have my knowledge foundation solidified and gain many insightful comments on my own study. For my migration to the field of linguistics, I thank Gladys Tang, my previous thesis supervisor when I was pursuing an MA degree in Linguistics. Only through interaction with her could I have an invaluable chance to be exposed to sign language: manifestation of communication ability of human beings in the visual-gestural modality. -

Heritage Impact Assessment Report for Yau Ma Tei Theatre Phase 2 At

Heritage Impact Assessment Report for Yau Ma Tei Theatre Phase 2 at Yau Ma Tei , Kowloon, Hong Kong Heritage Impact Assessment Report for Yau Ma Tei Theatre Phase 2 at Yau Ma Tei, Kowloon, Hong Kong Feb 2020 Rev. C Jan 2020 Rev. B Dec 2019 Rev. A Author Mr. LO Ka Yu, Henry BSSc (AS), MArch, MPhil (Arch), HKICON Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge the permission given by the following organisations and person for the use of their records, maps and photos in the report: . Antiquities and Monuments Office . Architectural Services Department . Information Services Department . Public Records Office . Survey & Mapping Office, Lands Department Table of Contents Heritage Impact Assessment Report for Yau Ma Tei Theatre Phase 2 at Yau Ma Tei, Kowloon, Hong Kong ......... iii List of Figures ................................................................................................................................................ ii Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Site particulars ................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................... -

Factory Name

Factory Name Factory Address BANGLADESH Company Name Address AKH ECO APPARELS LTD 495, BALITHA, SHAH BELISHWER, DHAMRAI, DHAKA-1800 AMAN GRAPHICS & DESIGNS LTD NAZIMNAGAR HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,1340 AMAN KNITTINGS LTD KULASHUR, HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH ARRIVAL FASHION LTD BUILDING 1, KOLOMESSOR, BOARD BAZAR,GAZIPUR,DHAKA,1704 BHIS APPARELS LTD 671, DATTA PARA, HOSSAIN MARKET,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1712 BONIAN KNIT FASHION LTD LATIFPUR, SHREEPUR, SARDAGONI,KASHIMPUR,GAZIPUR,1346 BOVS APPARELS LTD BORKAN,1, JAMUR MONIPURMUCHIPARA,DHAKA,1340 HOTAPARA, MIRZAPUR UNION, PS : CASSIOPEA FASHION LTD JOYDEVPUR,MIRZAPUR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH CHITTAGONG FASHION SPECIALISED TEXTILES LTD NO 26, ROAD # 04, CHITTAGONG EXPORT PROCESSING ZONE,CHITTAGONG,4223 CORTZ APPARELS LTD (1) - NAWJOR NAWJOR, KADDA BAZAR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH ETTADE JEANS LTD A-127-131,135-138,142-145,B-501-503,1670/2091, BUILDING NUMBER 3, WEST BSCIC SHOLASHAHAR, HOSIERY IND. ATURAR ESTATE, DEPOT,CHITTAGONG,4211 SHASAN,FATULLAH, FAKIR APPARELS LTD NARAYANGANJ,DHAKA,1400 HAESONG CORPORATION LTD. UNIT-2 NO, NO HIZAL HATI, BAROI PARA, KALIAKOIR,GAZIPUR,1705 HELA CLOTHING BANGLADESH SECTOR:1, PLOT: 53,54,66,67,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH KDS FASHION LTD 253 / 254, NASIRABAD I/A, AMIN JUTE MILLS, BAYEZID, CHITTAGONG,4211 MAJUMDER GARMENTS LTD. 113/1, MUDAFA PASCHIM PARA,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1711 MILLENNIUM TEXTILES (SOUTHERN) LTD PLOTBARA #RANGAMATIA, 29-32, SECTOR ZIRABO, # 3, EXPORT ASHULIA,SAVAR,DHAKA,1341 PROCESSING ZONE, CHITTAGONG- MULTI SHAF LIMITED 4223,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH NAFA APPARELS LTD HIJOLHATI,