Indian Independence and the Question of Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pakistan Studies) Courses

PAKISTAN STUDY CENTRE, UNIVERSITY OF SINDH, JAMSHORO M.PHIL (PAKISTAN STUDIES) COURSES Course work required for M.Phil (Pakistan Studies) is consisted of the following six courses-two semester. The credit hours for each course are given below: Paper Course Title of the Course Credit Marks No. Hours 1ST SEMESTER I PSC-800 Studies on Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah 4 100 II PSC-801 Political Parties in Pakistan 4 100 III PSC-802 Pakistan and the World 4 100 IV PSC-803 Research Methodology 4 100 2ND SEMESTER V PSC-804 Studies on the Freedom Fighters 4 100 VI PSC-805 Studies on Subsidiary Movements of Indo-Pak 4 100 - 1 - PAKISTAN STUDY CENTRE, UNIVERSITY OF SINDH, JAMSHORO STUDIES ON QUAID-I-AZAM MOHAMMAD ALI JINNAH M.PHIL PAKISTAN STUDIES The course will focus on the life, career and his struggle for a separate homeland of Muslims with special reference to his role as a parliamentarian, politician, leader of masses, nation builder, ideologue and his vision for Pakistan. COURSE NO.PSC-800 PAPER-I 1ST SEMESTER Family Background & Early Lifep 1. Family background and Birth of Jinnah 2. Early Education 3. Karachi 4. Bombay 5. Karachi 6. Marriage Education in London 1. Lincoln's Inn, London 2. Life in England 3. Early Influences As A Barrister 1. As a Barrister and Advocate of Bombay High Court 1896 2. Entry into Politics 1897-1906 Emergence as an All-India Leader 1906-1913 1. His Role in the Congress 2. Pleads Muslim Waqf Issue 3. Joining All-India Muslim League Leader of Both Congress and the Muslim League 1913-1920 1. -

The Khilafat Movement in India 1919-1924

THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT IN INDIA 1919-1924 VERHANDELINGEN VAN HET KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR T AAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE 62 THE KHILAFAT MOVEMENT IN INDIA 1919-1924 A. C. NIEMEIJER THE HAGUE - MAR TINUS NIJHOFF 1972 I.S.B.N.90.247.1334.X PREFACE The first incentive to write this book originated from a post-graduate course in Asian history which the University of Amsterdam organized in 1966. I am happy to acknowledge that the university where I received my training in the period from 1933 to 1940 also provided the stimulus for its final completion. I am greatly indebted to the personal interest taken in my studies by professor Dr. W. F. Wertheim and Dr. J. M. Pluvier. Without their encouragement, their critical observations and their advice the result would certainly have been of less value than it may be now. The same applies to Mrs. Dr. S. C. L. Vreede-de Stuers, who was prevented only by ill-health from playing a more active role in the last phase of preparation of this thesis. I am also grateful to professor Dr. G. F. Pijper who was kind enough to read the second chapter of my book and gave me valuable advice. Beside this personal and scholarly help I am indebted for assistance of a more technical character to the staff of the India Office Library and the India Office Records, and also to the staff of the Public Record Office, who were invariably kind and helpful in guiding a foreigner through the intricacies of their libraries and archives. -

1 Draft for Discussion Civil Services of Pakistan A

DRAFT FOR DISCUSSION CIVIL SERVICES OF PAKISTAN A PROPOSED FRAMEWORK RATIONALE FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE REFORM. A competent, effective and neutral Civil Service is the backbone of any country’s governance structure. Countries that do not have an Organized Civil Service system are at a relative disadvantage in executing their programs and policies. Pakistan was fortunate in having inherited a steel frame for its bureaucracy from the British. The purpose and motivation of the British in developing and supporting this steel frame were quite different from the requirements of an independent and sovereign country. This steel frame could, however, have been modified to suit and adapt to changed circumstances but there was not much point in dismantling the structure itself which had been built over a century. The major difficulty in the post independence period in Pakistan lay in the inability to replace the colonial practice of empowering the privileged class of executive/ bureaucratic system by a new democratic system of governance at local levels. The historical record of political institutional evolution in Pakistan is quite weak and that has had its toll on the quality of civil service overtime. The boundaries between policy making and execution got blurred, the equilibrium in working relationship between the Minister and Civil Servants remained shaky and uneasy and the sharing of decision making space remained contested and unsettled. The patrimonial state model with its attendant mai-bap culture and patronage dispensation mechanism remains intact in its essence although the form has changed many times over. The broadening of privileged class by the inclusion of military bureaucracy and political elites has only reinforced the patrimonial tendencies. -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

Shiism and Sectarian Conflict in Pakistan Identity Politics, Iranian Influence, and Tit-For-Tat Violence

Combating Terrorism Center at West Point Occasional Paper Series Shiism and Sectarian Conflict in Pakistan Identity Politics, Iranian Influence, and Tit-for-Tat Violence Hassan Abbas September 22, 2010 1 2 Preface As the first decade of the 21st century nears its end, issues surrounding militancy among the Shi‛a community in the Shi‛a heartland and beyond continue to occupy scholars and policymakers. During the past year, Iran has continued its efforts to extend its influence abroad by strengthening strategic ties with key players in international affairs, including Brazil and Turkey. Iran also continues to defy the international community through its tenacious pursuit of a nuclear program. The Lebanese Shi‛a militant group Hizballah, meanwhile, persists in its efforts to expand its regional role while stockpiling ever more advanced weapons. Sectarian violence between Sunnis and Shi‛a has escalated in places like Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Bahrain, and not least, Pakistan. As a hotbed of violent extremism, Pakistan, along with its Afghan neighbor, has lately received unprecedented amounts of attention among academics and policymakers alike. While the vast majority of contemporary analysis on Pakistan focuses on Sunni extremist groups such as the Pakistani Taliban or the Haqqani Network—arguably the main threat to domestic and regional security emanating from within Pakistan’s border—sectarian tensions in this country have attracted relatively little scholarship to date. Mindful that activities involving Shi‛i state and non-state actors have the potential to affect U.S. national security interests, the Combating Terrorism Center is therefore proud to release this latest installment of its Occasional Paper Series, Shiism and Sectarian Conflict in Pakistan: Identity Politics, Iranian Influence, and Tit-for-Tat Violence, by Dr. -

Dawood Hercules Corporation Limited List of Unclaimed Dividend / Shares

Dawood Hercules Corporation Limited List of Unclaimed Dividend / Shares Unclaimed Unclaimed S.No FOLIO NAME CNIC / NTN Address Shares Dividend 22, BAHADURABADROAD NO.2, BLOCK-3KARACHI-5 1 38 MR. MOHAMMAD ASLAM 00000-0000000-0 5,063 558/5, MOORE STREETOUTRAM ROADKARACHI 2 39 MR. MOHAMMAD USMAN 00000-0000000-0 5,063 FLAT NO. 201, SAMAR CLASSIC,KANJI TULSI DAS 3 43 MR. ROSHAN ALI 42301-1105360-7 STREET,PAKISTAN CHOWK, KARACHI-74200.PH: 021- 870 35401984MOB: 0334-3997270 34, AMIL COLONY NO.1SHADHU HIRANAND 4 47 MR. AKBAR ALI BHIMJEE 00000-0000000-0 ROADKARACHI-5. 5,063 PAKISTAN PETROLEUM LIMITED3RD FLOOR, PIDC 5 48 MR. GHULAM FAREED 00000-0000000-0 HOUSEDR. ZIAUDDIN AHMED ROADKARACHI. 756 C-3, BLOCK TNORTH NAZIMABADKARACHI. 6 63 MR. FAZLUR RAHMAN 00000-0000000-0 7,823 C/O. MUMTAZ SONS11, SIRAJ CLOTH 7 68 MR. AIJAZUDDIN 00000-0000000-0 MARKETBOMBAY BAZARKARACHI. 5,063 517-B, BLOCK 13FEDERAL 'B' AREAKARACHI. 8 72 MR. S. MASOOD RAZA 00000-0000000-0 802 93/10-B, DRIGH ROADCANTT BAZARKARACHI-8. 9 81 MR. TAYMUR ALI KHAN 00000-0000000-0 955 BANK SQUARE BRANCHLAHORE. 10 84 THE BANK OF PUNJAB 00000-0000000-0 17,616 A-125, BLOCK-LNORTH NAZIMABADKARACHI-33. 11 127 MR. SAMIULLAHH 00000-0000000-0 5,063 3, LEILA BUILDING, ABOVE UBLARAMBAGH ROAD, 12 150 MR. MUQIMUDDIN 00000-0000000-0 PAKISTAN CHOWKKARACHI-74200. 5,063 ZAWWAR DISPENSARYOPP. GOVT. COLLEGE FOR 13 152 MRS. KARIMA ABDUL RAHIM 00000-0000000-0 WOMENFRERE ROADKARACHI. 5,063 ZAWWAR DISPENSARYOPP. GOVT COLLEGE FOR 14 153 DR. ABDUL RAHIM GANDHI 00000-0000000-0 WOMENFRERE ROADKARACHI. -

Uttar Pradesh

Durham E-Theses Bureaucratic culture and new public management:: a case study of Indira Mahila Yojana in Uttar Pradesh Quirk, Alison Julia How to cite: Quirk, Alison Julia (2002) Bureaucratic culture and new public management:: a case study of Indira Mahila Yojana in Uttar Pradesh, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3760/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 BUREAUCRATIC CULTURE AND NEW PUBLIC MANAGEMENT: A CASE STUDY OF INDIRA MAHILA YOJANA IN UTIAR PRADESH Alison J ulia Quirk College of St. Hild and St. Bede Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2002 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author or the university to which it was submitted. No quotation from it, or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author or university, and any information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

Who Is Who in Pakistan & Who Is Who in the World Study Material

1 Who is Who in Pakistan Lists of Government Officials (former & current) Governor Generals of Pakistan: Sr. # Name Assumed Office Left Office 1 Muhammad Ali Jinnah 15 August 1947 11 September 1948 (died in office) 2 Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin September 1948 October 1951 3 Sir Ghulam Muhammad October 1951 August 1955 4 Iskander Mirza August 1955 (Acting) March 1956 October 1955 (full-time) First Cabinet of Pakistan: Pakistan came into being on August 14, 1947. Its first Governor General was Muhammad Ali Jinnah and First Prime Minister was Liaqat Ali Khan. Following is the list of the first cabinet of Pakistan. Sr. Name of Minister Ministry 1. Liaqat Ali Khan Prime Minister, Foreign Minister, Defence Minister, Minister for Commonwealth relations 2. Malik Ghulam Muhammad Finance Minister 3. Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar Minister of trade , Industries & Construction 4. *Raja Ghuzanfar Ali Minister for Food, Agriculture, and Health 5. Sardar Abdul Rab Nishtar Transport, Communication Minister 6. Fazal-ul-Rehman Minister Interior, Education, and Information 7. Jogendra Nath Mandal Minister for Law & Labour *Raja Ghuzanfar’s portfolio was changed to Minister of Evacuee and Refugee Rehabilitation and the ministry for food and agriculture was given to Abdul Satar Pirzada • The first Chief Minister of Punjab was Nawab Iftikhar. • The first Chief Minister of NWFP was Abdul Qayum Khan. • The First Chief Minister of Sindh was Muhamad Ayub Khuro. • The First Chief Minister of Balochistan was Ataullah Mengal (1 May 1972), Balochistan acquired the status of the province in 1970. List of Former Prime Ministers of Pakistan 1. Liaquat Ali Khan (1896 – 1951) In Office: 14 August 1947 – 16 October 1951 2. -

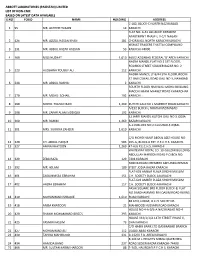

Abbott Laboratories (Pakistan) Limited List of Non-Cnic Based on Latest Data Available S.No Folio Name Holding Address 1 95

ABBOTT LABORATORIES (PAKISTAN) LIMITED LIST OF NON-CNIC BASED ON LATEST DATA AVAILABLE S.NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD 1 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 KARACHI FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN 2 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND 3 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KARACHI-74000. 4 169 MISS NUZHAT 1,610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 5 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 KARACHI NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD 6 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 KARACHI FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR 7 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 KARACHI 8 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1,269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD 9 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 KARACHI 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA 10 300 MR. RAHIM 1,269 BAZAR KARACHI A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL 11 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1,610 KARACHI C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 12 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. 13 327 AMNA KHATOON 1,269 47-A/6 P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI WHITEWAY ROYAL CO. 10-GULZAR BUILDING ABDULLAH HAROON ROAD P.O.BOX NO. 14 329 ZEBA RAZA 129 7494 KARACHI NO8 MARIAM CHEMBER AKHUNDA REMAN 15 392 MR. -

Federal Civil Service Commission (FCSC) Job Descriptions For

Federal Civil Service Commission (FCSC) Job Descriptions for Managerial Positions By- Rajeew Kumar Goel Sr. Civil Service Management Adviser USAID‐Tarabot, Iraq Administrative Reform Project February 2012 Federal Civil Service Commission (FCSC) Job Descriptions of Managerial Positions Sl. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. No. 1. Executive Summary 4‐5 2. Job Description of Directors General (Grade ‘B’) 6‐18 2.1 Finance and Administration Department 6 2.2 Legal Department 8 2.3 Administration Studies and Research Department 10 2.4 Public Administration Development Department 13 2.5 Coordination and Follow up with Ministries/ Agencies Department 16 3. Job Description of Director ‐15 posts (Grade‐2) 19‐ 51 3.1 Chairperson’s Office (1 post) I. Chairperson’s Office 19 3.2 Finance and Administration Department (4 posts) I. Planning, Finance & Budget Division 21 II. General Administration Division 23 III. Human Resource Division 26 IV. Information & Communications Technology (ICT) Division 28 3.3 Legal Department (3 posts) I. Legal Drafting Division 30 II. Legal Services and Litigation Division 32 III. Administrative Appeals Division 34 3.4 Administration Studies and Research Department (2 posts) I. Organization Research & Development Division 36 II. Monitoring and Evaluation Division 39 3.5 Public Administration Development Department (3 posts) I. Recruitment Division 41 II. Human Resource Policy Division 43 III. Training & Development Division 45 3.6 Coordination and Follow up with Ministries/ Agencies Department (2) I. Ministry, Government Agency & Provincial Relations Division 47 II. Communications & Public Relations Division 50 4. Job Description of Deputy Director ‐34 posts (Grade‐3) 52‐113 4.1 Chairperson’s Office (3 posts) 52 I. -

DC-3, Unit-11, Bi

Study Material for Sem-II , History(hons.) DC-3 ,Unit-II, b.i ARAB INVASION OF SIND Introduction Rise of Islam is an important incident in the history of Islam. Prophet Muhammad was not only the founder of a new religion, but he was also the head of a city-state. Muhammad left no male heir. On his death claims were made on behalf of his son-in-law and cousin Ali, but senior members of the community elected as their leader or caliph, the Prophet's companion, Abu Bakr, who was one of the earliest converts to Islam. Abu Bakr died after only two years in office, and was succeeded by Umar (r. 634-644 ), under whose leadership the Islamic community was transformed into a vast empire. Umar was succeeded by Usman (r. 644-656), who was followed by Ali (r. 656661), the last of the four "Righteous Caliphs." Owing to his relationship with the Prophet as well as to personal bravery, nobility of character, and intellectual and literary gifts, Caliph Ali occupies a special place in the history of Islam, but he was unable to control the tribal and personal quarrels of the Arabs. After his death, Muawiyah (r. 661- 680), the first of the Umayyad caliphs, seized power and transferred the seat of caliphate from Medina to Damascus. Three years later the succession passed from Muawiyah's grandson to another branch of the Umayyad dynasty, which continued in power until 750. During this period the Muslim armies overran Asia Minor, conquered the north coast of Africa, occupied Spain, and were halted only in the heart of France at Tours. -

From Exclusivism to Accommodation: Doctrinal and Legal Evolution of Wahhabism

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 79 MAY 2004 NUMBER 2 COMMENTARY FROM EXCLUSIVISM TO ACCOMMODATION: DOCTRINAL AND LEGAL EVOLUTION OF WAHHABISM ABDULAZIZ H. AL-FAHAD*t INTRODUCTION On August 2, 1990, Iraq attacked Kuwait. For several days there- after, the Saudi Arabian media was not allowed to report the invasion and occupation of Kuwait. When the Saudi government was satisfied with the U.S. commitment to defend the country, it lifted the gag on the Saudi press as American and other soldiers poured into Saudi Arabia. In retrospect, it seems obvious that the Saudis, aware of their vulnerabilities and fearful of provoking the Iraqis, were reluctant to take any public position on the invasion until it was ascertained * Copyright © 2004 by Abdulaziz H. AI-Fahad. B.A., 1979, Michigan State University; M.A., 1980, Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies; J.D., 1984, Yale Law School. Mr. Al-Fahad is a practicing attorney in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the Conference on Transnational Connec- tions: The Arab Gulf and Beyond, at St. John's College, Oxford University, September 2002, and at the Yale Middle East Legal Studies Seminar in Granada, Spain, January 10-13, 2003. t Editors' note: Many of the sources cited herein are available only in Arabic, and many of those are unavailable in the English-speaking world; we therefore have not been able to verify them in accordance with our normal cite-checking procedures. Because we believe that this Article represents a unique and valuable contribution to Western legal scholarship, we instead have relied on the author to provide translations or to verify the substance of particular sources where possible and appropriate.