Uttar Pradesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Draft for Discussion Civil Services of Pakistan A

DRAFT FOR DISCUSSION CIVIL SERVICES OF PAKISTAN A PROPOSED FRAMEWORK RATIONALE FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE REFORM. A competent, effective and neutral Civil Service is the backbone of any country’s governance structure. Countries that do not have an Organized Civil Service system are at a relative disadvantage in executing their programs and policies. Pakistan was fortunate in having inherited a steel frame for its bureaucracy from the British. The purpose and motivation of the British in developing and supporting this steel frame were quite different from the requirements of an independent and sovereign country. This steel frame could, however, have been modified to suit and adapt to changed circumstances but there was not much point in dismantling the structure itself which had been built over a century. The major difficulty in the post independence period in Pakistan lay in the inability to replace the colonial practice of empowering the privileged class of executive/ bureaucratic system by a new democratic system of governance at local levels. The historical record of political institutional evolution in Pakistan is quite weak and that has had its toll on the quality of civil service overtime. The boundaries between policy making and execution got blurred, the equilibrium in working relationship between the Minister and Civil Servants remained shaky and uneasy and the sharing of decision making space remained contested and unsettled. The patrimonial state model with its attendant mai-bap culture and patronage dispensation mechanism remains intact in its essence although the form has changed many times over. The broadening of privileged class by the inclusion of military bureaucracy and political elites has only reinforced the patrimonial tendencies. -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

Federal Civil Service Commission (FCSC) Job Descriptions For

Federal Civil Service Commission (FCSC) Job Descriptions for Managerial Positions By- Rajeew Kumar Goel Sr. Civil Service Management Adviser USAID‐Tarabot, Iraq Administrative Reform Project February 2012 Federal Civil Service Commission (FCSC) Job Descriptions of Managerial Positions Sl. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. No. 1. Executive Summary 4‐5 2. Job Description of Directors General (Grade ‘B’) 6‐18 2.1 Finance and Administration Department 6 2.2 Legal Department 8 2.3 Administration Studies and Research Department 10 2.4 Public Administration Development Department 13 2.5 Coordination and Follow up with Ministries/ Agencies Department 16 3. Job Description of Director ‐15 posts (Grade‐2) 19‐ 51 3.1 Chairperson’s Office (1 post) I. Chairperson’s Office 19 3.2 Finance and Administration Department (4 posts) I. Planning, Finance & Budget Division 21 II. General Administration Division 23 III. Human Resource Division 26 IV. Information & Communications Technology (ICT) Division 28 3.3 Legal Department (3 posts) I. Legal Drafting Division 30 II. Legal Services and Litigation Division 32 III. Administrative Appeals Division 34 3.4 Administration Studies and Research Department (2 posts) I. Organization Research & Development Division 36 II. Monitoring and Evaluation Division 39 3.5 Public Administration Development Department (3 posts) I. Recruitment Division 41 II. Human Resource Policy Division 43 III. Training & Development Division 45 3.6 Coordination and Follow up with Ministries/ Agencies Department (2) I. Ministry, Government Agency & Provincial Relations Division 47 II. Communications & Public Relations Division 50 4. Job Description of Deputy Director ‐34 posts (Grade‐3) 52‐113 4.1 Chairperson’s Office (3 posts) 52 I. -

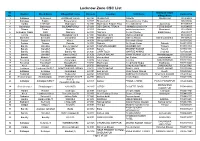

Lucknow Zone CSC List.Xlsx

Lucknow Zone CSC List Sl. Grampanchayat District Block Name Village/CSC name Pincode Location VLE Name Contact No No. Village Name 1 Sultanpur Sultanpur4 JAISINGHPUR(R) 228125 ISHAQPUR DINESH ISHAQPUR 730906408 2 Sultanpur Baldirai Bhawanighar 227815 Bhawanighar Sarvesh Kumar Yadav 896097886 3 Hardoi HARDOI1 Madhoganj 241301 Madhoganj Bilgram Road Devendra Singh Jujuvamau 912559307 4 Balrampur Balrampur BALRAMPUR(U) 271201 DEVI DAYAL TIRAHA HIMANSHU MISHRA TERHI BAZAR 912594555 5 Sitapur Sitapur Hargaon 261121 Hargaon ashok kumar singh Mumtazpur 919283496 6 Ambedkar Nagar Bhiti Naghara 224141 Naghara Gunjan Pandey Balal Paikauli 979214477 7 Gonda Nawabganj Nawabganj gird 271303 Nawabganj gird Mahmood ahmad 983850691 8 Shravasti Shravasti Jamunaha 271803 MaharooMurtiha Nafees Ahmad MaharooMurtiha 991941625 9 Badaun Budaun2 Kisrua 243601 Village KISRUA Shailendra Singh 5835005612 10 Badaun Gunnor Babrala 243751 Babrala Ajit Singh Yadav Babrala 5836237097 11 Bareilly Bareilly2 Bareilly Npp(U) 243201 TALPURA BAHERI JASVEER GIR Talpura 7037003700 12 Bareilly Bareilly3 Kyara(R) 243001 Kareilly BRIJESH KUMAR Kareilly 7037081113 13 Bareilly Bareilly5 Bareilly Nn 243003 CHIPI TOLA MAHFUZ AHMAD Chipi tola 7037260356 14 Bareilly Bareilly1 Bareilly Nn(U) 243006 DURGA NAGAR VINAY KUMAR GUPTA Nawada jogiyan 7037769541 15 Badaun Budaun1 shahavajpur 243638 shahavajpur Jay Kishan shahavajpur 7037970292 16 Faizabad Faizabad5 Askaranpur 224204 Askaranpur Kanchan ASKARANPUR 7052115061 17 Faizabad Faizabad2 Mosodha(R) 224201 Madhavpur Deepchand Gupta Madhavpur -

Raibareilly Dealers Of

Dealers of Raibareilly Sl.No TIN NO. UPTTNO FIRM - NAME FIRM-ADDRESS 1 09152400002 RB0012368 RAIBARALI GAN HOUSE KASARGANJ RAIBARALI 2 09152400016 RB0022220 S.VLAYAT ALI AND SONS KAISER GANJ,RAEBARELI 3 09152400021 RB0033437 SARARE PLASTIC PRV.LTD. SULTAN PUR ROAD,RAEBARELI 4 09152400040 RB0054810 SAHU MEDICAL STORE JAYAS RAIBARELI 5 09152400049 RB0035506 GARG INDUSTRISE SULTANPUR ROAD RAIBARELI 6 09152400054 RB0035025 BOMBAY TIMBER WORKS MANDI MANDI SAMITI ROAD RAIBARELI SAMITI 7 09152400068 RB0036205 GUPTA RADIOS HOSPITAL CHAURAHA RAEBARELI 8 09152400087 RB0013107 SHUKLA IORN TREDERS BACHHRAWAN,RAEBARELI 9 09152400092 RB0033312 TRIPATHI BROS. MEDI8CAL STORES HOSPITAL CHAURAHA,RAEBARELI 10 09152400101 RB0030556 RAIBARALI CYCLE INDUSTRIES SUPER MARKET RAIBARALI 11 09152400115 RB0038930 AGRAWAL AGENCY JAYAS RAIBARELI 12 09152400134 RB0040998 KRISHNA CHANDRA AGARWAL JAYAS RAEBARELI 13 09152400148 RB0044238 BOMBAY CYCLE MART KACHARI ROAD RBL 14 09152400153 RB0030657 JAIN MEDICAL STORE JAYAS RAIBARELI 15 09152400167 RB0046368 SUDHIR BHARGAWA PRABHU TOWN RAIBARELI 16 09152400172 RB0047787 RAJPOOT CONTRACTION COMP. SATYA NAGAR RAIBARELI 17 09152400186 RB0046607 VIVED STORES JAYAS RBL 18 09152400191 RB0046393 SHREE DHAR ENTERPRISES SULTANPUR ROAD RAIBARELI 19 09152400200 RB0048348 KAUSAL BRICK FIELD RAJA FATEHPUR RAEBARELI 20 09152400209 RB0048401 FANCY GENERAL STORES JAIS RAIBARELI 21 09152400214 RB0048599 RABI MOTER STORE CIVIL LINES RAIBARELI 22 09152400228 RB0049629 VIJAY MACH. STORES TILOI RBL 23 09152400233 RB0050009 KULVIR SINGH BACHARAWA -

B.A. (Public Administration)

NATIONAL EDUCATION POLICY-2020 COMMON MINIMUM SYLLABUS FOR ALL U.P. STATE UNIVERSITIES B.A. (PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION) NATIONAL EDUCATION POLICY-2020 COMMON MINIMUM SYLLABUS FOR ALL U.P. STATE UNIVERSTIES B.A. SYLLABUS SUBJECT: PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION NAME DESIGNTION AFFILIATION STEERING COMMITTEE Mrs. Monika S. Garg (I.A.S) Additional Chief Secretary Dept. of Higher Education U.P. Lucknow Chairperson Steering Committee Prof. Poonam Tandan Professor, Dept. of Physics Lucknow University, U.P. Prof. Hare Krishna Professor, Dept. of Statistics CCS University Meerut, U.P. Dr. Dinesh C. Sharma Associate Professor K.M. Govt. Girls P.G. College Badlapur, G.B. Nagar, U.P. Supervisory Committee- Arts and Humanities Stream Prof. Divya Nath Principal K.M. Govt. Girls P.G. College Badlapur, G.B. Nagar, U.P. Prof. Ajay Pratap Singh Dean, Faculty of Arts Ram Manohar Lohiya University, Ayodhya Dr. Nitu Singh Associate Professor HNB Govt. P.G. College ,Prayagraj Dr. Kishor Kumar Associate Professor K.M. Govt. Girls P.G. College ,Badlapur, G.B. Nagar, U.P. Dr. Shweta Pandey Assistant Professor Bundelkhand University, Jhansi Syllabus Developed by: S. No Name Designation Department College/ University 1- Professor Nandlal Bharti Professor Public University of Lucknow, LKO Administration 2- Dr. Sunita Tripathi Associate Public Siddharth University, Kapilvastu, Professor Administration Siddharthnagar 3- Dr. Ravi Kant Shukla Assistant Public Siddharth University, Kapilvastu, Professor Administration Siddharthnagar Department of Higher Education U.P. Government, -

Iasbaba 60 Day Plan 2020 – History Compilation Week 1 and 2

IASBABA 60 DAY PLAN 2020 – HISTORY COMPILATION WEEK 1 AND 2 IASBABA 1 IASBABA 60 DAY PLAN 2020 – HISTORY COMPILATION WEEK 1 AND 2 Q.1) Consider the following pairs: Land Revenue System Introduced by 1. Ryotwari Alexander Read 2. Mahalwari Thomas Munro 3. Permanent Settlement Lord Wellesley Which of the pairs given above are incorrectly matched? a) 1 and 2 only b) 3 only c) 2 and 3 only d) 1, 2 and 3 Q.1) Solution (c) Pair 1 Pair 2 Pair 3 Correct Incorrect Incorrect Ryotwari System was Mahalwari system was Zamindari System or introduced by Thomas Munro introduced by Holt Mackenzie Permanent Settlement was and Alexander Read in 1820. and Robert Merttins Bird in introduced by Lord Cornwallis Major areas of introduction 1833 in North-West Frontier, in 1793 through Permanent include Madras, Bombay, Agra, Central Province, Settlement Act. It was parts of Assam and Coorg Gangetic Valley, Punjab, etc. introduced in provinces of provinces of British India. It was introduced during the Bengal, Bihar, Orissa and period of William Bentick. Varanasi. Q.2) Factories at places like Bomlipatam, Chinsura, Balasore and Kasimbazar were established initially by? a) The Dutch b) The English c) The Portuguese d) The French Q.2) Solution (a) Portuguese Calicut (Kozhikode), Cochin, Cannanore (Kannur), Goa, Daman. factories IASBABA 2 IASBABA 60 DAY PLAN 2020 – HISTORY COMPILATION WEEK 1 AND 2 English Surat (1613), Agra, Ahmedabad and Broach, Bombay, Madras and Calcutta. factories French Surat, Masulipatnam, Pondicherry. factories Masulipatnam (1605), Pulicat (1610), Surat (1616), Bimlipatam (1641), Karikal Dutch (1645), Chinsurah (1653), Cassimbazar (Kasimbazar), Baranagore, Patna, factories Balasore, Nagapatam (1658) and Cochin (1663). -

Reforming Pakistan's Civil Service

REFORMING PAKISTAN’S CIVIL SERVICE Asia Report N°185 – 16 February 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE BUREAUCRACY................................................... 2 A. COLONIAL HERITAGE ..................................................................................................................2 B. CIVIL-MILITARY BUREAUCRATIC NEXUS (1947-1973)...............................................................3 C. BHUTTO’S ADMINISTRATIVE REFORMS........................................................................................5 D. THE CIVIL SERVICE UNDER ZIA-UL-HAQ .....................................................................................6 E. THE BUREAUCRACY UNDER CIVILIAN RULE ...............................................................................7 III. MILITARY RULE AND CIVIL SERVICE REFORM ................................................ 8 A. RESTRUCTURING DISTRICT ADMINISTRATION..............................................................................8 B. MILITARISING THE CIVIL SERVICES .............................................................................................9 C. REFORM ATTEMPTS ...................................................................................................................10 IV. CIVIL SERVICE STRUCTURE AND ORGANISATION........................................ -

Unit 5 Civil Service in the Context of Modern Bureaucracy

I UNIT 5 CIVIL SERVICE IN THE CONTEXT OF MODERN BUREAUCRACY Structure 5.0 Objqtives i 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Meaning of Bureaucracy 5.3 Types of Bureaucracy 5.4 Features of Bureaucracy 5.5 Role of Bureaucracy 5.6 Growing Importance of Bureaucracy in Recent Years 5.7 Merits and Demerits of Bureaucracy 5.8 Let Us Sum Up 5.9 Key Words 5.10 Some Useful Books 5.11 Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 5.0 OBJECTIVES After reading this unit you should be able to : state the meaning of bureaucracy and its various types 0' explain the various features of bureaucracy discuss the growing importance of bureaucracy in recent years describe the merits and demerits of bureaucracy; and highlight the expanding functions of bureaucracy. 5.1 INTRODUCTION Bureaucracy is an essential part of an organisation. Every organisation, whether big or small adheres to bureaucratic structure in some form or the other. Lately, the bureaucracy has come under severe criticism. Most people refer to it only negatively. Yet, despite its manifest defeciencies or exposed vices, no organisation, whether it is in governmental, public or private sector, has been able to do away with bureaucracy. On the contrary, all big institutions or organisations, for example, educational institutions, service agencies, research bodies, charitable trusts etc., have made the bureaucratic structure a vital part of their existence. Thus it can be stated that bureaucracy has a strong staying and survival capacity. Even the critics and opponents admit that there is more to be gained by keeping or retaining bureaucracy than abandoning it. -

Application No Rank

Application No Rank Candidate Name DOB Category Gender Email Mobile Address CHATRIWALI DHANI,MAHESHWARA ROAD IMUCET1422876 9509 RAJKUMAR MEENA 12-Jul-97 ST Male [email protected] 9950227724 DAUSA,DIST - DAUSA,Dausa-303303,Rajasthan VPO - KODYAI,TEH - BONLI,DIST - SAWAI IMUCET1418796 9503 OMPRAKASH MEENA 01-Aug-97 ST Male [email protected] 8696182466 MADHOPUR,Sawai Madhopur-322030,Rajasthan GANESH PUR,RAHMANPUR,CHINHAT IMUCET1413647 9501 MANISH KUMAR 20-Jul-97 SC Male [email protected] 7897989249 LUCKNOW,Lucknow-226028,Uttar Pradesh C-10 AKASHVANI COLONY,SECTOR-8 IMUCET1414405 9493 ANIVEH KUMAR 04-Jan-98 ST Male [email protected] 7408050958 OBRA,SONEBHADRA,Sonbhadra-231219,Uttar Pradesh VILL- POWER GANJ,GANESH RICE MILL PO- ANAITH,PS- IMUCET1422429 9483 ABHYMANU KUMAR 10-Aug-96 SC Male [email protected] 8521670288 * ARA NAWADA,Bhojpur-802301,Bihar 171,PURWA DIN DAYAL,ROORKEE,Rorkee- IMUCET1420839 9467 SACHIN 07-Apr-98 SC Male [email protected] 8439150233 247667,Uttarakhand V.P.O. UPPER LAMBA GAON,TEH. JAISINGHPUR,DISTT. IMUCET1416967 9447 SHUBHAM SONI 04-Nov-96 SC Male [email protected] 9736872264 KANGRA H.P.,Kangra-176096,Himachal Pradesh 007/75-B,EDENWALA CHAWL,J B MARG ELPHINSTONE IMUCET1408099 9448 DASHANKIT DATTATRAY LONDHE 04-Jan-97 SC Male [email protected] 8097948424 ROAD,Mumbai City-400025,Maharashtra E-L 3, SICHAI VIBHAG,,GOMTI BAIRAJ COLONY,BALOO IMUCET1420036 9453 SAURABH KUMAR 31-Dec-96 SC Male [email protected] 8115783483 ADDA,Lucknow-226001,Uttar Pradesh AT-KALYANPUR,PO-KALYANPUR,PS-BIDUPUR,DIST- -

List of Common Service Centres Established in Uttar Pradesh

LIST OF COMMON SERVICE CENTRES ESTABLISHED IN UTTAR PRADESH S.No. VLE Name Contact Number Village Block District SCA 1 Aram singh 9458468112 Fathehabad Fathehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 2 Shiv Shankar Sharma 9528570704 Pentikhera Fathehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 3 Rajesh Singh 9058541589 Bhikanpur (Sarangpur) Fatehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 4 Ravindra Kumar Sharma 9758227711 Jarari (Rasoolpur) Fatehabad Agra Vayam Tech. 5 Satendra 9759965038 Bijoli Bah Agra Vayam Tech. 6 Mahesh Kumar 9412414296 Bara Khurd Akrabad Aligarh Vayam Tech. 7 Mohit Kumar Sharma 9410692572 Pali Mukimpur Bijoli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 8 Rakesh Kumur 9917177296 Pilkhunu Bijoli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 9 Vijay Pal Singh 9410256553 Quarsi Lodha Aligarh Vayam Tech. 10 Prasann Kumar 9759979754 Jirauli Dhoomsingh Atruli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 11 Rajkumar 9758978036 Kaliyanpur Rani Atruli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 12 Ravisankar 8006529997 Nagar Atruli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 13 Ajitendra Vijay 9917273495 Mahamudpur Jamalpur Dhanipur Aligarh Vayam Tech. 14 Divya Sharma 7830346821 Bankner Khair Aligarh Vayam Tech. 15 Ajay Pal Singh 9012148987 Kandli Iglas Aligarh Vayam Tech. 16 Puneet Agrawal 8410104219 Chota Jawan Jawan Aligarh Vayam Tech. 17 Upendra Singh 9568154697 Nagla Lochan Bijoli Aligarh Vayam Tech. 18 VIKAS 9719632620 CHAK VEERUMPUR JEWAR G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 19 MUSARRAT ALI 9015072930 JARCHA DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 20 SATYA BHAN SINGH 9818498799 KHATANA DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 21 SATYVIR SINGH 8979997811 NAGLA NAINSUKH DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 22 VIKRAM SINGH 9015758386 AKILPUR JAGER DADRI G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 23 Pushpendra Kumar 9412845804 Mohmadpur Jadon Dankaur G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. 24 Sandeep Tyagi 9810206799 Chhaprola Bisrakh G.B.Nagar Vayam Tech. -

NORTHERN RAILWAY ASSETS-ACQUISITION, CONSTRUCTION and REPLACEMENT for 2014-15 (Figures in Thousand of Rupees) Item Particulars Allocation RE 2014-15 No

3.1.1 NORTHERN RAILWAY ASSETS-ACQUISITION, CONSTRUCTION AND REPLACEMENT FOR 2014-15 (Figures in thousand of Rupees) Item Particulars Allocation RE 2014-15 No. NEW LINES (CONSTRUCTION) A - Works in Progress 1 Nangal Dam-Talwara (83.74 km) - New broad gauge line & taking over siding Cap. 30,00,16 Mukerian-Talwara (29.16 km) 2 Abohar-Fazilka (42.717 km) Cap. 1,00,00 3 Tarantaran-Goindwal (21.5 km) Cap. 30,00 4 Chandigarh-Ludhiana (112 km) Cap. 20,25,00 EBR 5,00,00 5 Rewari-Rohtak (81.26 km) incl. new material modification for shifting of Rohtak - Cap. 12,00,00 Gohana - Panipat through bypass line EBR 20,00,00 6 Jind-Sonepat (88.9 km) Cap. 117,49,78 EBR 45,00,00 7 Jawarhar Lal Nehru Port-Tughlakabad-Dadri via Ahmedabad & Palanpur - Dedicated Cap. 764,00,00 multimodal high axle load freight corridor - Land acquisition 8 Dankuni - Ludhiana - Dedicated multimodal high axle load freight corridor - Land Cap. 286,00,00 acquisition 9 Chandigarh-Baddi (33.23 km) Cap. 13,00 EBR 2,00,00 10 Deoband (Muzaffarnagar)-Roorkee (27.45 km) Cap. 1,00,00 EBR 5,00,00 11 Bhanupalli-Bilaspur-Beri (63.1 km) Cap. 2,00,00 EBR 5,00,00 12 Rishikesh-Karnaprayag (125.09 km) Cap. 20,00,00 13 Qadian-Beas (39.68 km) Cap. 1 14 Unchahar-Amethi (66.17 km) Cap. 56,00 15 Rohtak-Meham-Hansi (68.8 km) Cap. 1,00,00 EBR 10,00,00 16 Delhi - Sohna - Nuh - Firozpur Jhirka - Alwar (104 km) Cap.