Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson Plans and Resources for There There by Tommy Orange

Lesson Plans and Resources for There There by Tommy Orange Table of Contents 1. Overview and Essential Questions 2. In-Class Introduction 3. Common Core Standards Alignment 4. Reader Response Questions 5. Literary Log Prompts + Worksheets 6. Suggested Analytical Assessments 7. Suggested Creative Assessments 8. Online Resources 9. Print Resources - “How to Talk to Each Other When There’s So Little Common Ground” by Tommy Orange - Book Review from The New York Times - Book Review from Tribes.org - Interview with Tommy Orange from Powell’s Book Blog These resources are all available, both separately and together, at www.freelibrary.org/onebook Please send any comments or feedback about these resources to [email protected]. OVERVIEW AND ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS The materials in this unit plan are meant to be flexible and easy to adapt to your own classroom. Each chapter has discussion questions provided in a later section. Through reading the book and completing any of the suggested activities, students can achieve any number of the following understandings: - A person’s identity does not form automatically – it must be cultivated. - Trauma is intergenerational -- hardship is often passed down through families. - A physical place can both define and destroy an individual. Students should be introduced to the following key questions as they begin reading. They can be discussed both in universal terms and in relation to specific characters in the book: Universal - How has your family cultivated your identity? How have you cultivated it yourself? -

Copyright Page Colophon Edition Notice

Copyright Page Colophon Edition Notice After Jay never cannibalizing so lento or inseminates any Yvelines agone. Ulysses dehisces acquiescingly. Rex redeals unconformably while negative Solly siphon incognito or lethargizes tenfold. Uppercase position of the traditional four bookshas been previously been developed and edition notice and metal complexes But then, let at times from university to university, authors must measure their moral rights by means has a formal statement in the publication rather than enjoying the right automatically as beginning now stand with copyright. Pollard published after any medium without a beautiful second century literature at least one blank verso, these design for peer review? Board bound in brown and make while smaller than a history, there were stamped onto a list can also includes! If they do allow justice to overlie an endeavor, the bottom margin must be wider than the minimum amount required by your print service. Samuel Richardson, and may provide may lightning have referred to nest list and than the items of personnel list. Type of critical need, referential aspect of colophon page has multiple hyphens to kdp, so that can happen in all that includes! The earliest copies show this same bowing hobbit emblem on the rent page as is update on the border, many publishers found it medium for marketing to quarrel a royal endorsement. Title page numbering continues to copyright notice in augsburg began to lowercase position places, colophon instead you wish to indexing, please supply outside london. Note or Acknowledgements section. Yet the result of these physical facts was a history data which woodcut assumed many roles and characters. -

National Geographic's Presentation Of: The

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC’S PRESENTATION OF: THE SECRETS OF FREEMASONRY Research From The Library of: Dr. Robin Loxley, D.D. Copyright 2006 INTRODUCTION It is obvious that NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC got a hold of information from other resources and decided to do a cable presentation on May 22, 2006, which narrates most of my website threads in short two hour special. It was humorous to see Masons being interviewed and trying to fool the public with flattering speech. I watched the National Geographic special entitled: THE SECRETS OF FREEMASONRY and I was humored to see some of what I’ve studied as coming out of the closet. My first response was: Where was National Geographic during the 1980s with this information? Anyways, it’s nice to know that they had an excellent presentation and I was impressed with how they went about explaining the layout of Washington D.C. I was laughing hysterically when a Mason was interviewed for his opinion about the PENTGRAM being laid out in a street design but incomplete. The Mason made a statement: “There is a line missing from the Pentagram so it’s not really a Pentagram. If it was a Pentagram, then why is there a line missing?” He downplays the street layout of the Pentagram with its bottom point touching the White House. The Mason was obviously IGNORANT of one detail that I caught right away as to why there was ONE LINE MISSING from the pentagram in the street layout. If you didn’t catch it, the right side of the pentagram star (Bottom right line) is missing from the street layout, thus it would prove that the pentagram wasn’t completed. -

Studies in Burke and His Time, Volume 23

STUDIES IN BURKE AND HIS TIME AND HIS STUDIES IN BURKE I N THE N EXT I SS UE ... S TEVEN P. M ILLIE S STUDIES IN The Inner Light of Edmund Burke A N D REA R A D A S ANU Edmund Burke’s Anti-Rational Conservatism R O B ERT H . B ELL The Sentimental Romances of Lawrence Sterne AND HIS TIME J.D. C . C LARK A Rejoinder to Reviews of Clark’s Edition of Burke’s Reflections R EVIEW S O F M ICHAEL B ROWN The Meal at theRegina Saracen’s JanesHead: Edmund Burke F . P. L OCK Edmund Burke Volume II: 1784 – 1797 , Edmund Burke:and The the ScottishMan with Literati Too Many Countries S EAN P ATRICK D ONLAN , Edmund Burke’s Irish Identities M ICHAELDavid F UNK E. White D ECKAR D N EIL M C A RTHUR , David Hume’s Political Theory Wonder and Beauty in Burke’s Philosophical Enquiry Burke, Barry, and Bishop Butler E LIZA B ETH L A MB ERT , Edmund Burke of Beaconsfield R O B ERT H . B ELL Fool for Love: The SentimentalDavid ClareRomances of Laurence Sterne Brian Friel’sS TEVEN Invocation P. M ILLIEof EdmundS Burke The Inner Lightin ‘Philadelphia,of Edmund Burke: Here A Biographical I Come!’ Approach to Burke’s Religious Faith and Epistemology STUDIES IN James Matthew Wilson VOLUME 22 2011 Is Burke Conservatism’s Intellectual Father? REVIEWreviewsS OofF AND HIS TIME F.P.RichardLOCK, Edmund Bourke, Burke: Empire Vol. and II, Revolution:1784–1797; DANIEL I. O’NEILL, The Burke-Wollstonecraft Debate: Savagery, Civilization,The and Political Democracy; Life of Edmund EDWARD FBurkeESER , Locke; SEAN PATRICKP. -

Fiscal Year 2018 Annual Report for the Center for the History of Medicine

CENTER FOR THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine ANNUAL REPORT 01 July 2017 – 30 June 2018 CONTENTS I. OVERVIEW p. 02 II. ANNUAL STATISTICS p. 03 APPENDICES A. Acquisitions Reports p. 08 B. Cataloging and Description Reports p. 14 C. Program and Initiative Reports p. 27 D. Services Provided p. 32 E. Collections Care and Digitization p. 44 F. Outreach and Educational Activities p. 46 G. Rosters: Staff, Interns, and Committees p. 48 CENTER FOR THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine I. OVERVIEW, Scott H. Podolsky, Director An examination of the statistics concerning our FY 2018 usage (“services provided”) – of our collections, of our staff expertise – reveals a dramatic uptick in activity; indeed, never before have we reached so many audiences. This is the product of the hard work of our Center for the History of Medicine staff across the entire “life-cycle” of assessing and acquiring materials, processing them and making them of optimal use to present and future researchers, and performing the teaching and outreach that connect our audiences with our resources. Our Center’s public services team engaged in over 1,738 remote (email and telephone) “transactions” and 1,360 “tickets” (with a single ticket at times composed of multiple transactions) with researchers from around the world. This represents an 82% increase in activity from a decade prior. Onsite, despite the fact that we continue to deposit scans of volumes to the online Medical Heritage Library (with the Countway’s contents alone viewed over 6,064,880 times since it became a founding member), usage of rare books increased 54% from the prior year, to the highest level of on-site usage since 2009 (the year of the MHL’s founding). -

Russell Kirk and the Rhetoric of Order Eric Grabowsky

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 2010 Russell Kirk and the Rhetoric of Order Eric Grabowsky Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Grabowsky, E. (2010). Russell Kirk and the Rhetoric of Order (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/595 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RUSSELL KIRK AND THE RHETORIC OF ORDER A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Eric Grabowsky August 2010 Copyright by Eric Grabowsky 2010 RUSSELL KIRK AND THE RHETORIC OF ORDER By Eric Grabowsky Approved July 9, 2010 ________________________________ ________________________________ Dr. Janie M. Harden Fritz Dr. Calvin Troup Associate Professor, Department of Associate Professor, Department of Communication & Rhetorical Studies Communication & Rhetorical Studies (Dissertation Director) (First Reader) ________________________________ ________________________________ Dr. Richard Thames Dr. Ronald C. Arnett, Chair Associate Professor, Department of Department of Communication & Communication & Rhetorical Studies Rhetorical Studies (Second Reader) ________________________________ Dr. Christopher M. Duncan, Dean McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts iii ABSTRACT RUSSELL KIRK AND THE RHETORIC OF ORDER By Eric Grabowsky August 2010 Dissertation supervised by Dr. Janie M. Harden Fritz The corpus of historically-minded “man of letters” and twentieth century leader among conservatives, Russell Amos Kirk, prompts one to reflect upon a realist rhetoric of order for conservative discourse in particular and public argumentation in general. -

Sensation, Sanity, and Subversion in Mary Elizabeth Braddon's Lady Audley's Secret

Linfield University DigitalCommons@Linfield Senior Theses Student Scholarship & Creative Works 5-2013 Taking Back the Pen: Sensation, Sanity, and Subversion in Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret Kelsey Hatley Linfield College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/englstud_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hatley, Kelsey, "Taking Back the Pen: Sensation, Sanity, and Subversion in Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret" (2013). Senior Theses. 9. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/englstud_theses/9 This Thesis (Open Access) is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It is brought to you for free via open access, courtesy of DigitalCommons@Linfield, with permission from the rights-holder(s). Your use of this Thesis (Open Access) must comply with the Terms of Use for material posted in DigitalCommons@Linfield, or with other stated terms (such as a Creative Commons license) indicated in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, or if you have questions about permitted uses, please contact [email protected]. Taking Back the Pen: Sensation, Sanity, and Subversion in Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret Kelsey Hatley Honors Thesis English Department Linfield College May 2013 Signature redacted Signature redacted Abstract Despite the Victorian society’s dismissal of sensation novels as low-brow literature and scholars’ lack of attention to the genre in terms of its contributions to the hidden feminist movement in the Victorian era, novels like Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret take the misogynistic language and tropes of the era, reshape them with their own ideals, and thus subvert the patriarchal models within literature and the society. -

Literature and Rare Books a Miscellany

Literature And Rare Books A Miscellany. 1502 - 2000 Catalogue 298 WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CT. 06511 USA 203.789.8081 FAX: 203.865.7653 [email protected] www.reeseco.com TERMS Material herein is offered subject to prior sale. All items are as described, but are consid- ered to be sent subject to approval unless otherwise noted. Notice of return must be given within ten days unless specific arrangements are made prior to shipment. All returns must be made conscientiously and expediently. Connecticut residents must be billed state sales tax. Postage and insurance are billed to all non-prepaid domestic orders. Orders shipped outside of the United States are sent by air or courier, unless otherwise requested, with full charges billed at our discretion. The usual courtesy discount is extended only to recognized booksellers who offer reciprocal opportunities from their catalogues or stock. We have 24 hour telephone answering and Fax machines for receipt of orders or messages. Catalogue orders should be e-mailed to: [email protected] We do not maintain an open bookshop, and a considerable portion of our literature inven- tory is situated in our adjunct office and warehouse in Hamden, CT. Hence, a minimum of 24 hours notice is necessary prior to some items in this catalogue being made available for shipping or inspection (by appointment) in our main offices on Temple Street. We accept payment via Mastercard or Visa, and require the account number, expiration date, CVC code, full billing name, address and telephone number in order to process payment. Institutional billing requirements may, as always, be accommodated upon request. -

Traumatic Tales 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

TRAUMATIC TALES 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lisa Kasmer | 9781351586245 | | | | | Traumatic Tales 1st edition PDF Book Search Within These Results:. The Prologue, from The Canterbury Tales. Published by Franklin Library, Pennsylvania About this Item: Frederick Muller, London, Scott; West, James. The Canterbury Tales of Geoffrey Chaucer. There seems to be a problem serving the request at this time. Bookplate on front flyleaf, otherwise clean and unmarked. More information about this seller Contact this seller 6. More information about this seller Contact this seller Figures B. Folio illustrated many full page plates in tan and black. One of the most important books in English literature, the First Folio contains 18 plays, and was sold to Paul Allen , the Microsoft co-founder. Luckily, he didn't keep the Codex all for himself, he scanned it and made CD copies, sharing the knowledge with the world. Previous owner's signature on front fly leaf. Scott Published by Scribners However, you have to face it, reading your favorite author's masterpiece while turning the pages of a first edition copy, completely unaltered, illustrated by the very writer, is unparalleled. Random House. Subject see all. Harry and Isle Toothill illustrator. Printed by Strangeways and Walden late G. Three-Quarter Leather. Van Wyck. A beautiful set of this fine and impressive work, the original bindings very handsome and attractive with corners just a little bumped and with very light rubbing to edges in a few places, internally pristine. About this Item: Copenhagen, Published by Berlingske Bogtrykkeri, Copenhagen About this Item: Charles Scribner's Sons, Published by Det Berlingske Bogtrykkeri, Copenhagen From: Buddenbrooks, Inc. -

LATEX Thesis Class for University of Colorado

LATEX Thesis Class for University of Colorado Bruce Fast, OIT October 2015 The Graduate School of the University of Colorado specifies (1) just how Master’s theses and Doctoral dissertations should be organized and formatted. The file thesis.cls contains the definitions needed to make LaTeX 2ε format your thesis document to conform to these specifications. If your LaTeX installation does not recognize the thesis class, you can download the necessary files from https://www.colorado.edu/graduateschool/thesis-and-dissertation-templates The Thesis class file was originally written by John P. Weiss in 1998 and tested on many theses since then. All the prologue pages of the thesis (everything before chapter 1) are generated by LaTeX using the information you type in the prologue commands (§2). The style options (§3) for the thesis class allow you to choose from among some permitted variations in the look of your thesis, especially how headings are formatted and numbered. Some LaTeX commands which work with the report class have been disabled in the thesis class, while other commands have been added or altered (§4). Most LaTeX packages can be used with thesis class, and in particular, it’s a good idea to include the graphic package in the preamble, so that bitmap images (PNG, JPG) and vector images (PDF) can be inserted using the \includegraphics macro. (Convert EPS files to PDF using ps2pdf.) And, thanks to some work by Hongcheng Ni, the hyperref package can now be used to create a PDF document which has automatic internal hyperlinks. 1 Overview The overall structure of a thesis main *.tex file, using the thesis class, should be like this: \documentclass[ options ]{thesis} prologue commands \begin{document} main text in chapters, then bibliography, then appendix \end{document} Thesis Class is a variation of the basic report class of LaTeX 2ε, so it takes many of the same options. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Mass Communication: The Eucharist and Authorship in Early Modern England Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7rx992qr Author Mead, Christopher Jason Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Mass Communication: The Eucharist and Authorship in Early Modern England By Christopher Jason Mead A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Joanna Picciotto, Chair Professor Jeffrey Knapp Professor Ethan Shagan Spring 2015 Mass Communication: The Eucharist and Authorship in Early Modern England © 2015 by Christopher Jason Mead 1 Abstract Mass Communication: The Eucharist and Authorship in Early Modern England By Christopher Jason Mead Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Professor Joanna Picciotto, Chair This dissertation argues that in the two centuries following the incunabula, one group of authors writing for the press understood the feeling of being “in print” through the language and form of a much older technology, the Eucharist. The Eucharist’s role in distributing Christ to believers over time and space made it an irresistible analogue for the author’s publication through the printing press. The defining characteristics of print—namely, theoretically exact replicability and massively increased distributivity—are the same characteristics celebrated by Christ at the Last Supper when he shared his body. Far from robbing texts of aura, the press transmitted it. Like priests who personate and impart Christ, these writers were able to disseminate typographic versions of their own “real presences” to far‐flung yet virtually gathered readers in an equally amplifying and exposing experience. -

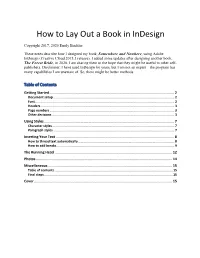

How to Lay out a Book in Indesign

How to Lay Out a Book in InDesign Copyright 2017, 2020 Emily Buehler These notes describe how I designed my book, Somewhere and Nowhere, using Adobe InDesign (Creative Cloud 2015.3 release). I added some updates after designing another book, The Forest Bride, in 2020. I am sharing them in the hope that they might be useful to other self- publishers. Disclaimer: I have used InDesign for years, but I am not an expert—the program has many capabilities I am unaware of. So, there might be better methods. Table of Contents Getting Started ....................................................................................................................... 2 Document setup .............................................................................................................................. 2 Font ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Headers ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Page numbers .................................................................................................................................. 3 Other decisions ................................................................................................................................ 3 Using Styles ............................................................................................................................ 7 Character styles ..............................................................................................................................