Download Minsters and Valleys for FREE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Rail MHLSI Works.Pub

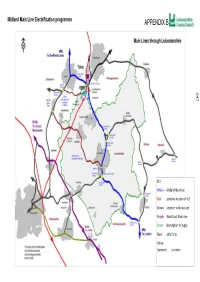

Midland Main Line Electrification programme 247 KEY MMLe — Midland Main Line Red potenal locaon of Hs2 Brown Leicester to Burton Line Purple West Coast Main Line Green Birmingham to ugby Black other lines Yellow diamonds %uncons POST HENDY REVIEW—UPDATE The Hendy Enhancements delivery plan update (Jan 2016) Electrification of the Midland Main Line has resumed under plans announced as part of Sir Peter Hendy’s work to reset Network Rail’s upgrade programme. Work on electrifying the Midland Main Line, the vital long-distance corridor that serves the UK’s industrial heartland, will continue alongside the line-speed and capacity improvement works that were already in hand. Electrification of the line north of Bedford to Kettering and Corby is scheduled to be completed by 2019, and the line north of Kettering to Leicester, Derby/Nottingham and Sheffield by 2023. Outputs The Midland Main line Electrification Programme known as the MMLe is split into two key output dates, the first running from 2014-2019 (known as CP5) and the second, 2019-2023 (CP6). There are a number of sub projects running under the main MMLe programme which are delivering various improvements in the Leicestershire area. Each sub project has dependencies with each other to enable the full ES001- Midland Main Line electrification programme to be achieved A number of interfaces and assumptions link to these programmes and their sub projects will affect Leicestershire. ES001A- Leicester Capacity The proposed 4 tracking between Syston and Wigston is located under sub project ES001A - Leicester Capacity which can be found on page 27 of Network Rails enhancements delivery plan . -

Memorials of Old Wiltshire I

M-L Gc 942.3101 D84m 1304191 GENEALOGY COLLECTION I 3 1833 00676 4861 Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 with funding from Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center http://www.archive.org/details/memorialsofoldwiOOdryd '^: Memorials OF Old Wiltshire I ^ .MEMORIALS DF OLD WILTSHIRE EDITED BY ALICE DRYDEN Editor of Meinoriah cf Old Northamptonshire ' With many Illustrations 1304191 PREFACE THE Series of the Memorials of the Counties of England is now so well known that a preface seems unnecessary to introduce the contributed papers, which have all been specially written for the book. It only remains for the Editor to gratefully thank the contributors for their most kind and voluntary assistance. Her thanks are also due to Lady Antrobus for kindly lending some blocks from her Guide to Amesbury and Stonekenge, and for allowing the reproduction of some of Miss C. Miles' unique photographs ; and to Mr. Sidney Brakspear, Mr. Britten, and Mr. Witcomb, for the loan of their photographs. Alice Dryden. CONTENTS Page Historic Wiltshire By M. Edwards I Three Notable Houses By J. Alfred Gotch, F.S.A., F.R.I.B.A. Prehistoric Circles By Sir Alexander Muir Mackenzie, Bart. 29 Lacock Abbey .... By the Rev. W. G. Clark- Maxwell, F.S.A. Lieut.-General Pitt-Rivers . By H. St. George Gray The Rising in the West, 1655 . The Royal Forests of Wiltshire and Cranborne Chase The Arundells of Wardour Salisbury PoHtics in the Reign of Queen Anne William Beckford of Fonthill Marlborough in Olden Times Malmesbury Literary Associations . Clarendon, the Historian . Salisbury .... CONTENTS Page Some Old Houses By the late Thomas Garner 197 Bradford-on-Avon By Alice Dryden 210 Ancient Barns in Wiltshire By Percy Mundy . -

Location and History Setting

LOCATION AND HISTORY Great Bowden lies midway between Leicester and Northampton on the Leicestershire side of the county boundary, surrounded by the rich pastureland of the Welland Valley and located in hunting country. Although almost contiguous to the town of Market Harborough, Great Bowden retains its individuality and village character. The two settlements were formally separated in 1995 when Great Bowden was granted parish status. The village comprises approximately 449 houses and had a population of 1017 according to the 2011 census Aerial Photograph of Great Bowden and the surrounding hills Great Bowden, mentioned in the Domesday Book (1086), was once the centre of a Saxon royal estate. By royal charter (1203) its neighbour, Market Harborough, was established as a trading centre, which became the commercial staging post in the district. Although Market Harborough now dominates the area, Great Bowden still maintains its separate identity, with Agriculture continuing to be the main local economy. Towards the end of the 19th century until the l920's Great Bowden was well known for its horse breeding, which has since been replaced by its hunting interests,being the base for the Fernie Hunt. The construction of the Grand Union Canal in 1809 provided a fuel supply and transport system for the local brickyard, whose products are still in evidence in the village. The canal's brief period of importance was challenged by the construction of the local railway in 1850, which split the village in half, compromising its historic integrity. In recognition of its special character a large part of the settlement has been designated a Conservation Area, which includes most of the older buildings within the village. -

TRANSFORMING PURTON PARISH Foresight and Resilience (Threats and Opportunities) Ps and Qs January 2013

TRANSFORMING PURTON PARISH Foresight and Resilience (Threats and Opportunities) Ps and Qs January 2013 1 | P a g e CONTENTS ABOUT Ps and Qs ............................................................................................................................... 3 FOR CLARIFICATION ......................................................................................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 4 1. Sustainability ................................................................................................................................ 5 2. Key Parish Issues ........................................................................................................................ 9 3. Our Parish .................................................................................................................................. 11 3.1 Our Water ............................................................................................................................. 12 3.2 Our Food ............................................................................................................................... 19 3.3 Our Energy ............................................................................................................................ 26 3.4 Our Waste ............................................................................................................................ -

Accounting for National Nature Reserves

Natural England Research Report NERR078 Accounting for National Nature Reserves: A Natural Capital Account of the National Nature Reserves managed by Natural England www.gov.uk/naturalACCOUNTING FOR-england NATIONAL NATURE RESERVES Natural England Research Report NERR078 Accounting for National Nature Reserves: A Natural Capital Account of the National Nature Reserves managed by Natural England Tim Sunderland1, Ruth Waters1, Dan Marsh2, Cat Hudson1 and Jane Lusardi1 Published 21st February 2019 1 Natural England 2 University of Waikato, New Zealand This report is published by Natural England under the Open Government Licence - OGLv3.0 for public sector information. You are encouraged to use, and reuse, information subject to certain conditions. For details of the licence visit Copyright. Natural England photographs are only available for non commercial purposes. If any other information such as maps or data cannot be used commercially this will be made clear within the report. ISBN 978-1-78354-518-6 © Natural England 2018 ACCOUNTING FOR NATIONAL NATURE RESERVES Project details This report should be cited as: SUNDERLAND, T., WATERS, R.D., MARSH, D. V. K., HUDSON, C., AND LUSARDI, J. (2018). Accounting for National Nature Reserves: A natural capital account of the National Nature Reserves managed by Natural England. Natural England Research Report, Number 078 Project manager Tim Sunderland Principal Specialist in Economics Horizon House Bristol BS1 5TL [email protected] Acknowledgements We would like to thank everyone who contributed to this report both within Natural England and externally. ii Natural England Research Report 078 Foreword England’s National Nature Reserves (NNRs) are the crown jewels of our natural heritage. -

WILTSHIRE. F.AR 1111 Sharp Samuel, West End Mill, Donhead Smith Thomas, Everleigh, Marlborough Stride Mrs

TRADES DIRECTORY. J WILTSHIRE. F.AR 1111 Sharp Samuel, West End mill, Donhead Smith Thomas, Everleigh, Marlborough Stride Mrs. Jas. Whiteparish, Salisbury St. Andrew, Salisbury Smith William, Broad Hinton, Swindon Strong George, Rowde, Devizes Sharpe Mrs. Henry, Ludwell, Salisbury Smith William, Winsley, Bradford Strong James, Everleigh, Marlborough Sharpe Hy. Samuel, Ludwell, Salisbury Smith William Hugh, Harpit, Wan- Strong Willialll, Draycot, Marlborough Sharps Frank, South Marston, Swindon borough, ShrivenhamR.S.O. (Berks) Strong William, Pewsey S.O Sharps Robert, South Marston, Swindon Snelgar John, Whiteparish, Salisbury Stubble George, Colerne, Chippenham Sharps W. H. South Marston, Swindon Snelgrove David, Chirton, De,·izes Sumbler John, Seend, Melksham Sheate James, Melksham Snook Brothers, Urchfont, Devizes SummersJ.&J. South Wraxhall,Bradfrd Shefford James, Wilton, Marlborough Snook Albert, South Marston, Swindon Summers Edwd. Wingfield rd. Trowbrdg ShepherdMrs.S.Sth.Burcombe,Salisbury Snook Mrs. Francis, Rowde, Devizes Sutton Edwd. Pry, Purton, Swindon Sheppard E.BarfordSt.Martin,Salisbury Snook George, South Marston, Swindon Sutton Fredk. Brinkworth, Chippenham Shergold John Hy. Chihnark, Salisbury EnookHerbert,Wick,Hannington,Swndn Sutton F. Packhorse, Purton, Swindon ·Sbewring George, Chippenham Snook Joseph, Sedghill, Shaftesbury Sutton Job, West Dean, Salisbury Sidford Frank, Wilsford & Lake farms, Snook Miss Mary, Urchfont, Devizes Sutton·John lllake, Winterbourne Gun- Wilsford, Salisbury Snook Thomas, Urchfont, Devizes ner, Salisbury "Sidford Fdk.Faulston,Bishopstn.Salisbry Snook Worthr, Urchfont, Devizes Sutton Josiah, Haydon, Swindon Sidford James, South Newton, Salisbury Somerset J. Milton Lilborne, Pewsey S.O Sutton Thomas Blake, Hurdcott, Winter Bimkins Job, Bentham, Purton, Swindon Spackman Edward, Axrord, Hungerford bourne Earls, Salisbury Simmons T. GreatSomerford, Chippenhm Spackman Ed. Tytherton, Chippenham Sutton William, West Ha.rnham,Salisbry .Simms Mrs. -

From 1 September 2020

from 1 September 2020 routes Calne • Marlborough via Avebury 42 Mondays to Fridays except public holidays these journeys operate via Heddington Wick, Heddington, Calne The Pippin, Sainsbury's 0910 1115 1303 1435 1532 1632 1740 Stockley and Rookery Park. They also serve Yatesbury to set Calne Post Office 0911 0933 1116 1304 1436 1533 1633 1741 down passengers only if requested and the 1532 and 1740 Calne The Strand, Bank House 0730 0913 0935 1118 1306 1438 1535 1635 1743 journey will also serve Blacklands on request Kingsbury Green Academy 1537 1637 these journeys operate via Kingsbury Quemerford Post Office 0733 0916 0938 1121 1309 1441 R R R Green Academy on schooldays only Lower Compton Turn (A4) 0735 0918 0940 1123 1313 1443 R R R Lower Compton Spreckley Road 0942 R 1315 R R R Compton Bassett Briar Leaze 0948 R 1321 R R Cherhill Black Horse 0737 0920 1125 1329 1445 R R R Beckhampton Stables 0742 0925 1130 1334 1450 R R R Avebury Trusloe 0743 0926 1131 1335 1451 R R R Avebury Red Lion arrive 0745 0928 1133 1337 1453 R R R Winterbourne Monkton 0932 R Berwick Bassett Village 0935 R Avebury Red Lion depart 0745 0940 1143 1343 1503 1615 1715 West Kennett Telephone Box 0748 0943 1146 1346 1506 1618 1718 East Kennett Church Lane End 0750 0945 1148 1348 R R West Overton Village Stores 0753 0948 1151 1351 R R Lockeridge Who'd A Thought It 0757 0952 1155 1355 R R Fyfield Bath Road 0759 0954 1157 1357 1507 1621 1726 Clatford Crossroads 0801 0957 1200 1400 R Manton High Street 0803 0959 1202 1402 R Barton Park Morris Road, Aubrey Close 0807 0925 1003 1205 1405 1510 R R Marlborough High Street 0812 0929 1007 1210 1410 1515 1630 1740 Marlborough St Johns School 0820 serves Marlborough operates via these journeys operate via Blacklands to St Johns School on Yatesbury to set set down passengers only if requested. -

Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge Review

Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge Review September 2020 2 Contents Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge Review .......................................................... 1 August 2020 .............................................................................................................. 1 Role of this Evidence Base study .......................................................................... 6 Evidence Base Overview ................................................................................... 6 1. Introduction ................................................................................................. 7 General Description of Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge........................... 7 Figure 1: Map showing the extent of the Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge 8 2. Policy background ....................................................................................... 9 Formulation of the Green Wedge ....................................................................... 9 Policy context .................................................................................................... 9 National Planning Policy Framework (2019) ...................................................... 9 Core Strategy (December 2009) ...................................................................... 10 Site Allocations and Development Management Policies Development Plan Document (2016) ............................................................................................. 10 Landscape Character Assessment (September 2017) .................................... -

Thames River Basin Management Plan, Including Local Development Documents and Sustainable Community Strategies ( Local Authorities)

River Basin Management Plan Thames River Basin District Contact us You can contact us in any of these ways: • email at [email protected] • phone on 08708 506506 • post to Environment Agency (Thames Region), Thames Regional Office, Kings Meadow House, Kings Meadow Road, Reading, Berkshire, RG1 8DQ The Environment Agency website holds the river basin management plans for England and Wales, and a range of other information about the environment, river basin management planning and the Water Framework Directive. www.environment-agency.gov.uk/wfd You can search maps for information related to this plan by using ‘What’s In Your Backyard’. http://www.environment-agency.gov.uk/maps. Published by: Environment Agency, Rio House, Waterside Drive, Aztec West, Almondsbury, Bristol, BS32 4UD tel: 08708 506506 email: [email protected] www.environment-agency.gov.uk © Environment Agency Some of the information used on the maps was created using information supplied by the Geological Survey and/or the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and/or the UK Hydrographic Office All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior permission of the Environment Agency. Environment Agency River Basin Management Plan, Thames River Basin District 2 December 2009 Contents This plan at a glance 5 1 About this plan 6 2 About the Thames River Basin District 8 3 Water bodies and how they are classified 11 4 The state of the water environment now 14 5 Actions to improve the water environment by 2015 19 6 The state of the water -

Appendix 14.1 Archaeological Desk Based Assessment

APPENDIX 14.1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL DESK BASED ASSESSMENT ANDOVER BUSINESS PARK Andover County of Hampshire Archaeological desk–based assessment June 2007 Archaeology Service ANDOVER BUSINESS PARK Andover County of Hampshire Archaeological desk–based assessment National Grid Reference: 433000 145700 Project Manager Stewart Hoad Reviewed by Jon Chandler Author Helen Dawson Graphics Carlos Lemos Museum of London Archaeology Service © Museum of London 2007 Mortimer Wheeler House, 46 Eagle Wharf Road, London N1 7ED tel 020 7410 2200 fax 020 7410 2201 email [email protected] web www.molas.org.uk Archaeological desk-based assessment MoLAS 2007 Contents 1 Introduction 2 1.1 Origin and scope of the report 2 1.2 Site status 2 1.3 Aims and objectives 2 2 Methodology and sources consulted 4 3 Legislative and planning framework 6 3.1 National planning policy guidance 6 3.2 Regional guidance: 6 3.3 Local Planning Policy 7 4 Archaeological and historical background 9 4.1 Site location, topography and geology 9 4.2 Overview of past archaeological investigations 10 4.3 Chronological summary 11 5 Archaeological potential 20 5.1 Factors affecting archaeological survival 20 5.2 Archaeological potential 20 6 Impact of proposals 22 6.1 Proposals 22 6.2 Implications 22 7 Conclusions and recommendations 24 8 Acknowledgements 25 9 Gazetteer of known archaeological sites and finds 26 10 Bibliography 29 10.1 Published and documentary sources 29 10.2 Other Sources 30 10.3 Cartographic sources 30 i P:\HAMP\1021\na\Field\DBA_22-06-07.doc Archaeological desk-based assessment -

Berwick Bassett and Winterbourne Monkton Parish Council

Berwick Bassett and Winterbourne Monkton Parish Council Minutes of the meeting of the council held at Winterbourne Monkton Church on Wednesday 9th September 2015 at 7.30pm. Present: Cllr Bill Buxton (chair), Cllr Nick Burnet, Cllr Stephen Fulford, Cllr Tony Iles, Cllr Jill Petchey Mrs Janice Pattison (clerk) Mr Tim Pearce 1. Apologies for absence Cllr Lyn Bennett-Nutt 2. Declaration of Interests None of the councillors had interests in the items on the agenda 3. Questions from the public There were no questions from members of the public present 4. Minutes of meetings of 8th July 2015 and 14th August 2015 The minutes of the both meetings were accepted as a true reflection of the meeting 5. Matters Arising from meeting of 14th August 2015 The clerk had contacted Aster Housing regarding the availability of garage occupancy at the Beeches. Aster Housing will investigate 6. Reports a. Finance The clerk reported that no cheques have been presented since the last meeting The current spend is below budget. Current account balance is £2612.43 savings is £836 Planned spending for the remainder of the year is approximately £1000 The anticipated ‘savings’ (income over expenditure) this year is anticipated to be approximately £300 An invoice for church rental year to date was presented b. Planning 15/0080/ENF Christmas House, Winterbourne Monkton 15/00112/ENF New Inn, Winterbourne Monkton There has been no action yet on these issues. It was reported that there were people living in The New Inn. Cllr Buxton will follow up both enforcement issues to determine what if any progress had been made. -

Leicester's Green Infrastructure Strategy

LEICESTER GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE STRATEGY 2015-2025 EVIDENCE BASE, ACTIONS AND OPPORTUNITIES 1 | P a g e FOREWORD This framework sets out the strategic vision for our green sites in Leicester and the ways in which they can be created, managed and maintained to provide maximum benefits to the people who live, work or visit Leicester. The actions are supported by an evidence base of data and information which recognise and prioritise key areas where resources can be focussed to develop high quality green infrastructure (GI) into our new and existing communities. By placing the framework within the planning system it is possible to provide the key tools needed to secure these areas and design them to provide multi- functional green space. Improvements to established green space and creating new sites to surround built development will provide an accessible and natural green network. These areas will be capable of supporting a range of functions which include landscaping/public amenity, recreation, flood control, safer access routes, cooler areas to combat predicted climate change and places for wildlife. These functions give rise to a range of environmental and quality of life benefits which include providing attractive and distinctive places to live, work and play; improving public health, facilitating access and encouraging sustainable transport as well as offering an environment to support wildlife. Placing a monetary value on these benefits is difficult, but many have potential to deliver significant economic value by increasing the attractiveness of a neighbourhood for businesses and employers, encouraging tourism and associated revenue, reducing health care costs and maintenance or clean-up costs from flooding.