Leicester's Green Infrastructure Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OLDER PERSONS BOOKLET 2011AW.Indd

Older Persons’ Community Information Leicestershire and Rutland 2011/2012 Friendship Dignity Choice Independence Wellbeing Value Events planned in Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland in 2011. Recognition Directory of Information and Services for Older People. Leicestershire County and Rutland Thank you With thanks to all partner organisations involved in making September Older Persons’ Month 2011 a success: NHS Leicestershire County and Rutland – particularly for the major funding of the printing of this booklet Communities in Partnership (CiP) – for co-ordinating the project Leicestershire County Council – for co-funding the project Age Concern Leicester Shire and Rutland – particularly for acting as the host for the launch in Leicester NHS Leicester City and Leicester City Council - for close partnership working University Hospitals of Leicester Rutland County Council Blaby District Council Melton Borough Council Charnwood Borough Council North West Leicestershire District Council Harborough District Council Hinckley and Bosworth Borough Council Oadby and Wigston Borough Council Voluntary Actions in Blaby, Charnwood, North-West Leics, South Leicestershire, Hinckley and Bosworth, Melton, Oadby and Wigston and Rutland The Older People’s Engagement Network (OPEN) The Co-operative Group (Membership) The following for their generous support: Kibworth Harcourt Parish Council, Ashby Woulds Parish Council, Fleckney Parish Council, NHS Retirement Fellowship With special thanks to those who worked on the planning committee and the launch sub-group. -

East Midlands Derby

Archaeological Investigations Project 2007 Post-determination & Research Version 4.1 East Midlands Derby Derby UA (E.56.2242) SK39503370 AIP database ID: {5599D385-6067-4333-8E9E-46619CFE138A} Parish: Alvaston Ward Postal Code: DE24 0YZ GREEN LANE Archaeological Watching Brief on Geotechnical Trial Holes at Green Lane, Derbyshire McCoy, M Sheffield : ARCUS, 2007, 18pp, colour pls, figs, tabs, refs Work undertaken by: ARCUS There were no known earthworks or findspots within the vicinity of the site, but traces of medieval ridge and furrow survived in the woodlands bordering the northern limits of the proposed development area. Despite this, no archaeological remains were encountered during the watching brief. [Au(adp)] OASIS ID :no (E.56.2243) SK34733633 AIP database ID: {B93D02C0-8E2B-491C-8C5F-C19BD4C17BC7} Parish: Arboretum Ward Postal Code: DE1 1FH STAFFORD STREET, DERBY Stafford Street, Derby. Report on a Watching Brief Undertaken in Advance of Construction Works Marshall, B Bakewell : Archaeological Research Services, 2007, 16pp, colour pls, figs, refs Work undertaken by: Archaeological Research Services No archaeological remains were encountered during the watching brief. [Au(adp)] OASIS ID :no (E.56.2244) SK35503850 AIP database ID: {5F636C88-F246-4474-ABF7-6CB476918678} Parish: Darley Ward Postal Code: DE22 1EB DARLEY ABBEY PUMP HOUSE, DERBY Darley Abbey Pump House, Derby. Results of an Archaeological Watching Brief Shakarian, J Bakewell : Archaeological Research Services, 2007, 14pp, colour pls, figs, refs, CD Work undertaken -

River Soar & Grand Union Canal Partnership

) 5 1 0 2 . 1 1 B R ( m a e T t n e m e g a n a M d n a r B & g n i t e k r a M l i c n u o C y t i C r e t s e c i e L y b d e c u d o r P The River Soar and Grand Union Canal Partnership River Soar & Grand Union Canal Partnership If you would like to know more, go to http:/www.leics.gov.uk/index/environment/countryside/environment management/river soar strategy.htm 2016 / 2019 Action Plan 1 Executive Summary Members of the Partnership The River Soar and Grand Union Canal sustainability of the corridor, together with a Chaired by the City Mayor, River Soar and corridor is a fascinating, complex and vibrant strong commitment to partnership working. Grand Union Canal Corridor Partnership thread that weaves its way through the comprises representatives of public county. Its value as a strategic wildlife corridor By carefully protecting and enhancing its authorities, statutory bodies and charitable and its potential for economic regeneration historic environment, and the natural wild and voluntary organisations. It meets regularly has long been recognised, but remains to be habitats that make it special, the River Soar to consider how, by working together, it can fully realised. and Grand Union Canal Partnership can promote the long term regeneration and harness the potential of the waterway to make sustainability of the waterway corridor. Balancing the needs of this living and working it more attractive to visitors, for business landscape is key to the long term success and opportunities and as a place to work and live. -

Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge Review

Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge Review September 2020 2 Contents Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge Review .......................................................... 1 August 2020 .............................................................................................................. 1 Role of this Evidence Base study .......................................................................... 6 Evidence Base Overview ................................................................................... 6 1. Introduction ................................................................................................. 7 General Description of Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge........................... 7 Figure 1: Map showing the extent of the Rothley Brook Meadow Green Wedge 8 2. Policy background ....................................................................................... 9 Formulation of the Green Wedge ....................................................................... 9 Policy context .................................................................................................... 9 National Planning Policy Framework (2019) ...................................................... 9 Core Strategy (December 2009) ...................................................................... 10 Site Allocations and Development Management Policies Development Plan Document (2016) ............................................................................................. 10 Landscape Character Assessment (September 2017) .................................... -

Proposed Mineral Allocation Site on Land Off Pincet Lane, North Kilworth, Leicestershire

Landscape and Visual Appraisal for: Proposed Mineral Allocation Site on Land off Pincet Lane, North Kilworth, Leicestershire Report Reference: CE - NK-0945-RP01a- FINAL 26 August 2015 Produced by Crestwood Environmental Ltd. Crestwood Report Reference: CE - NK-0945-RP01a- FINAL: Issued Version Date Written / Updated by: Checked & Authorised by: Status Produced Katherine Webster Karl Jones Draft v1 17-08-15 (Landscape Architect) (Director) Katherine Webster Karl Jones Final 18-08-15 (Landscape Architect) (Director) Katherine Webster Karl Jones Final Rev A 26-08-15 (Landscape Architect) (Director) This report has been prepared in good faith, with all reasonable skill, care and diligence, based on information provided or known available at the time of its preparation and within the scope of work agreement with the client. We disclaim any responsibility to the client and others in respect of any matters outside the scope of the above. The report is provided for the sole use of the named client and is confidential to them and their professional advisors. No responsibility is accepted to others. Crestwood Environmental Ltd. Units 1 and 2 Nightingale Place Pendeford Business Park Wolverhampton West Midlands WV9 5HF Tel: 01902 824 037 Email: [email protected] Web: www.crestwoodenvironmental.co.uk Landscape and Visual Appraisal Proposed Quarry at Pincet Lane, North Kilworth CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 2 1.1 SITE -

Older Persons' Booklet 2011

Older Persons’ Community Information Leicestershire and Rutland 2011/2012 Friendship Dignity Choice Independence Wellbeing Value Events planned in Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland in 2011. Recognition Directory of Information and Services for Older People. Leicestershire County and Rutland Thank you Welcome to Older Persons’ Month 2011 With thanks to all partner organisations involved in making The first Older Persons’ Month was in September 2002 and proved to be such September Older Persons’ Month 2011 a success: a popular and productive initiative that it was agreed to establish this as an annual event. NHS Leicestershire County and Rutland – particularly for the major funding of The theme this year is ‘Independence, Wellbeing, Community’. All of the the printing of this booklet activities listed in this booklet aim to promote positive messages about later life, Communities in Partnership (CiP) – for co-ordinating the project to encourage everyone approaching and past retirement age to keep active and Leicestershire County Council – for co-funding the project healthy, and to give information about services and activities which are available. Age Concern Leicester Shire and Rutland – particularly for acting as the host for the launch in Leicester Activities and events include the involvement of a wide range of local NHS Leicester City and Leicester City Council - for close partnership working organisations working together – including the local NHS Primary Care Trusts, University Hospitals of Leicester Adults and Communities Department, Borough and District Councils, Voluntary Rutland County Council Sector Organisations, Adult Education, Library Services, Emergency Services, Blaby District Council Community Groups, local commercial interests and local older people. Melton Borough Council Charnwood Borough Council You are welcome to attend any of the events listed. -

Managing Challenging Behaviour in Meetings

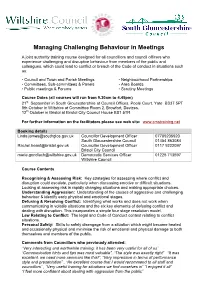

Managing Challenging Behaviour in Meetings A joint authority training course designed for all councillors and council officers who experience challenging and disruptive behaviour from members of the public and colleagues, which could lead to conflict or breach of the Code of conduct in situations such as: • Council and Town and Parish Meetings • Neighbourhood Partnerships • Committees, Sub-committees & Panels • Area Boards • Public meetings & Forums • Scrutiny Meetings Course Dates (all courses will run from 9.30am to 4.45pm) 21 st September in South Gloucestershire at Council Offices, Poole Court, Yate BS37 5PT 8th October in Wiltshire at Committee Room 2, Browfort, Devizes. 12 th October in Bristol at Bristol City Council House BS1 5TR For further information on the facilitators please see web site: www.cmstraining.net Booking details [email protected] Councillor Development Officer 07789205920 South Gloucestershire Council 01454 863084 [email protected] Councillor Development Officer 0117 9222097 Bristol City Council [email protected] Democratic Services Officer 01225 713597 Wiltshire Council Course Contents Recognising & Assessing Risk: Key strategies for assessing where conflict and disruption could escalate, particularly when discussing emotive or difficult situations. Looking at assessing risk in rapidly changing situations and making appropriate choices. Understanding Aggression: Understanding of the causes of aggressive and challenging behaviour & identify early physical and emotional stages. Defusing & Resolving Conflict: Identifying what works and does not work when communicating in volatile situations and the six key elements of defusing conflict and dealing with disruption. This incorporates a simple four stage resolution model. Law Relating to Conflict: The legal and Code of Conduct context relating to conflict situations. -

26 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

26 bus time schedule & line map 26 Leicester - Groby - Ratby - Thornton - Bagworth - View In Website Mode Ellistown - Coalville The 26 bus line (Leicester - Groby - Ratby - Thornton - Bagworth - Ellistown - Coalville) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bagworth: 6:28 PM (2) Coalville: 6:12 AM - 6:12 PM (3) Leicester: 6:19 AM - 5:03 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 26 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 26 bus arriving. Direction: Bagworth 26 bus Time Schedule 18 stops Bagworth Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 6:28 PM Marlborough Square, Coalville Marlborough Square, England Tuesday 6:28 PM Avenue Road, Coalville Wednesday 6:28 PM 185 Belvoir Road, England Thursday 6:28 PM North Avenue, Coalville Friday 6:28 PM 182 Central Road, Hugglescote And Donington Le Heath Civil Parish Saturday 6:28 PM Fairƒeld Road, Hugglescote 78 Central Road, Hugglescote And Donington Le Heath Civil Parish Post O∆ce, Hugglescote 26 bus Info Station Road, Hugglescote Direction: Bagworth Stops: 18 The Common, Hugglescote Trip Duration: 15 min Line Summary: Marlborough Square, Coalville, Sherwood Close, Ellistown Avenue Road, Coalville, North Avenue, Coalville, Fairƒeld Road, Hugglescote, Post O∆ce, Parkers Close, Ellistown Hugglescote, Station Road, Hugglescote, The Common, Hugglescote, Sherwood Close, Ellistown, Amazon, Bardon Parkers Close, Ellistown, Amazon, Bardon, Amazon, Bardon, Parkers Close, Ellistown, Working Mens Club, Amazon, Bardon Ellistown, Primary School, Ellistown, -

Leicester City Council Overview & Scrutiny Handbook

Leicester City Council Overview & Scrutiny Handbook Publication Agreed at Overview Select Committee of 22/09/12 Introduction by Chair of Overview Select Committee I want scrutiny to be as effective as possible in Leicester City Council and this Handbook will help to achieve that. It is designed to help all those involved in scrutiny. To do this we have tried to pull together in one place all of the current information about scrutiny. It contains advice, guidance, and the rules and regulations governing how scrutiny works. For me scrutiny has three main purposes: holding the City Mayor to account, holding the council and other organisations to account and generating ideas and policy. These functions are important in ensuring that the Council is run democratically by involving all members and providing the primary checks and balances on the power of the City Mayor and his cabinet. Scrutiny Commissions will look at the expenditure, administration and policy of the cabinet portfolio they cover. All members should be involved in scrutiny. Members of Scrutiny Committees will involve themselves and contribute to the work of their committee. Executive members will attend, answer questions, explain decisions and policy and the strategy they are pursuing. Officers will attend and be prepared to brief members and answer questions about finance, administration and policy. The spirit of scrutiny should be that of genuine enquiry in our efforts to improve the council and the city for all its citizens. Scrutiny should be conducted without fear of consequences or promise of favour. I hope this handbook will be useful in helping us in our scrutiny work Ross Willmott Chair Overview Select Committee “When the people fear the government, there is tyranny. -

Annex F –List of Consultees

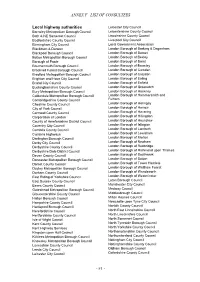

ANNEX F –LIST OF CONSULTEES Local highway authorities Leicester City Council Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council Leicestershire County Council Bath & NE Somerset Council Lincolnshire County Council Bedfordshire County Council Liverpool City Council Birmingham City Council Local Government Association Blackburn & Darwen London Borough of Barking & Dagenham Blackpool Borough Council London Borough of Barnet Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Bexley Borough of Poole London Borough of Brent Bournemouth Borough Council London Borough of Bromley Bracknell Forest Borough Council London Borough of Camden Bradford Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Croydon Brighton and Hove City Council London Borough of Ealing Bristol City Council London Borough of Enfield Buckinghamshire County Council London Borough of Greenwich Bury Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hackney Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hammersmith and Cambridgeshire County Council Fulham Cheshire County Council London Borough of Haringey City of York Council London Borough of Harrow Cornwall County Council London Borough of Havering Corporation of London London Borough of Hillingdon County of Herefordshire District Council London Borough of Hounslow Coventry City Council London Borough of Islington Cumbria County Council London Borough of Lambeth Cumbria Highways London Borough of Lewisham Darlington Borough Council London Borough of Merton Derby City Council London Borough of Newham Derbyshire County Council London -

Wi Speakers List

WI SPEAKERS LIST ART & LITERATURE Wet on Wet Oil Painting Demonstration * Landscape - Seascape - Floral Jayne Good Broughton Astley, Leicester 01455 282981/07968 495177 £45 [email protected] Available anytime Murder and Mayhem - Bestselling local crime novelist talks about the challenges of writing detective fiction in the modern age, including an insight into the research required and the workings of the publishing industry Jane Isaac Northamptonshire 07969 065479 £40 + 45p per mile over 10 mile radius from home [email protected] A Fun Oil Painting Demo with an unscripted, go with the flow approach – ideal for those with no particular interest in art! Humorous talk on Life as an Artist with the emphasis on entertainment – with audience participation! Mike Peachey Wellingborough, Northants. 07977 580429 £50 + 33p per mile travel [email protected] Available evenings, day talks subject to availability mikeartorguk.workpress.com My Life as an Artist * Cruising for the Uninitiated Michaela Kelly Thorpe Satchville, Leics. 01664 840731 £40 plus mileage [email protected] COUNTRYSIDE & NATURE Helping Hedgehogs Colleen Powell Leicester 0116 2207844 £60 including travel [email protected] Available daytime and evenings The Woodland Trust & National Forest Ian Retson Ashby de la Zouch, Leics. 01530 415682/07969 191493 Donation to charity [email protected] Available anytime My Life and Times in Farming and Hedge Laying Clive Matthew Desford, Leicester 01455 824055/07703 827548 £1.50 pp, donated to DCL Holidays -

Title 42 Point Poppins Semi Bold

Onstreet Residential Chargepoint Scheme Successful Applicants 18 / 19 Broadhembury Parish Council Buckinghamshire County Council Cardiff City Council Coventry City Council Cranbrook and Sissinghurst Parish Council Dundee City Council East Lindsey District Council East Lothian Council Lambeth Council Lancaster City Council Liverpool City Council London borough of Waltham Forest Luton Borough Council Nottingham City Council Portsmouth City Council South Norfolk Council South Tyneside Council ORCS resources 1 Stirling Council Tadley Town Council Welwyn Parish Council West Berkshire Council West Lindsey District Council West Suffolk Councils ORCS resources 2 19 / 20 Barnsley Council Boston Borough Council Breckland and South Holland Council Brent Council Brighton Council Calderdale Council Canterbury City Council Carmarthenshire County Council Cheshire West and Chester Borough Council Chichester District Council Coventry City Council Derbyshire County Council Dundee City Council East Lothian Council East Riding of Yorkshire Essex County Council Great Yarmouth Borough Council Gwent County Borough Council Halton Borough Council Hovingham Parish Council Isle of Wight ORCS resources 3 Kettering Borough Council Leicester City Council London Borough of Bexley London Borough of Camden London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham London Borough of Harrow London Borough of Islington North Norfolk Portsmouth City Council Powys County Council Reading Borough Council Richmond Council South Kesteven District Council South Tyneside Council Swansea Council