Laboratory-Acquired Brucellosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ehrlichiosis

Ehrlichiosis What is ehrlichiosis and can also have a wide range of signs Who should I contact, if I what causes it? including loss of appetite, weight suspect ehrlichiosis? Ehrlichiosis (air-lick-ee-OH-sis) is a loss, prolonged fever, weakness, and In Animals – group of similar diseases caused by bleeding disorders. Contact your veterinarian. In Humans – several different bacteria that attack Can I get ehrlichiosis? the body’s white blood cells (cells Contact your physician. Yes. People can become infected involved in the immune system that with ehrlichiosis if they are bitten by How can I protect my animal help protect against disease). The an infected tick (vector). The disease organisms that cause ehrlichiosis are from ehrlichiosis? is not spread by direct contact with found throughout the world and are Ehrlichiosis is best prevented by infected animals. However, animals spread by infected ticks. Symptoms in controlling ticks. Inspect your pet can be carriers of ticks with the animals and humans can range from frequently for the presence of ticks bacteria and bring them into contact mild, flu-like illness (fever, body aches) and remove them promptly if found. with humans. Ehrlichiosis can also to severe, possibly fatal disease. Contact your veterinarian for effective be transmitted through blood tick control products to use on What animals get transfusions, but this is rare. your animal. ehrlichiosis? Disease in humans varies from How can I protect myself Many animals can be affected by mild infection to severe, possibly fatal ehrlichiosis, although the specific infection. Symptoms may include from ehrlichiosis? bacteria involved may vary with the flu-like signs (chills, body aches and The risk for infection is decreased animal species. -

Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis Are Tick-Borne Diseases Caused by Obligate Anaplasmosis: Intracellular Bacteria in the Genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma

Ehrlichiosis and Importance Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are tick-borne diseases caused by obligate Anaplasmosis: intracellular bacteria in the genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma. These organisms are widespread in nature; the reservoir hosts include numerous wild animals, as well as Zoonotic Species some domesticated species. For many years, Ehrlichia and Anaplasma species have been known to cause illness in pets and livestock. The consequences of exposure vary Canine Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, from asymptomatic infections to severe, potentially fatal illness. Some organisms Canine Hemorrhagic Fever, have also been recognized as human pathogens since the 1980s and 1990s. Tropical Canine Pancytopenia, Etiology Tracker Dog Disease, Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are caused by members of the genera Ehrlichia Canine Tick Typhus, and Anaplasma, respectively. Both genera contain small, pleomorphic, Gram negative, Nairobi Bleeding Disorder, obligate intracellular organisms, and belong to the family Anaplasmataceae, order Canine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, Rickettsiales. They are classified as α-proteobacteria. A number of Ehrlichia and Canine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Anaplasma species affect animals. A limited number of these organisms have also Equine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, been identified in people. Equine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Recent changes in taxonomy can make the nomenclature of the Anaplasmataceae Tick-borne Fever, and their diseases somewhat confusing. At one time, ehrlichiosis was a group of Pasture Fever, diseases caused by organisms that mostly replicated in membrane-bound cytoplasmic Human Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, vacuoles of leukocytes, and belonged to the genus Ehrlichia, tribe Ehrlichieae and Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, family Rickettsiaceae. The names of the diseases were often based on the host Human Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, species, together with type of leukocyte most often infected. -

Human Babesiosis and Ehrlichiosis Current Status

IgeneX_v1_A4_A4_2011 27/04/2012 17:26 Page 49 Tick-borne Infectious Disease Human Babesiosis and Ehrlichiosis – Current Status Jyotsna S Shah,1 Richard Horowitz2 and Nick S Harris3 1. Vice President, IGeneX Inc., California; 2. Medical Director, Hudson Valley Healing Arts Center, New York; 3. CEO and President, IGeneX Inc., California, US Abstract Lyme disease (LD), caused by the Borrelia burgdorferi complex, is the most frequently reported arthropod-borne infection in North America and Europe. The ticks that transmit LD also carry other pathogens. The two most common co-infections in patients with LD are babesiosis and ehrlichiosis. Human babesiosis is caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Babesia including Babesia microti, Babesia duncani, Babesia divergens, Babesia divergens-like (also known as Babesia MOI), Babesia EU1 and Babesia KO1. Ehrlichiosis includes human sennetsu ehrlichiosis (HSE), human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA), human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME), human ewingii ehrlichiosis (HEE) and the recently discovered human ehrlichiosis Wisconsin–Minnesota (HWME). The resulting illnesses vary from asymptomatic to severe, leading to significant morbidity and mortality, particularly in immunocompromised patients. Clinical signs and symptoms are often non-specific and require the medical provider to have a high degree of suspicion of these infections in order to be recognised. In this article, the causative agents, geographical distribution, clinical findings, diagnosis and treatment protocols are discussed for both babesiosis and ehrlichiosis. Keywords Babesia, Ehrlichia, babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, human, Borrelia Disclosure: Jyotsna Shah and Nick Harris are employees of IGeneX. Richard Horowitz is an employee of Hudson Valley Healing Arts Center. Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Eddie Caoili, and Sohini Stone, for providing technical assistance. -

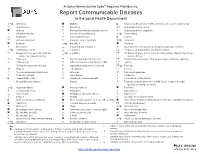

Report Communicable Diseases to the Local Health Department

Arizona Administrative Code Requires Providers to: Report Communicable Diseases to the Local Health Department *O Amebiasis Glanders O Respiratory disease in a health care institution or correctional facility Anaplasmosis Gonorrhea * Rubella (German measles) Anthrax Haemophilus influenzae, invasive disease Rubella syndrome, congenital Arboviral infection Hansen’s disease (Leprosy) *O Salmonellosis Babesiosis Hantavirus infection O Scabies Basidiobolomycosis Hemolytic uremic syndrome *O Shigellosis Botulism *O Hepatitis A Smallpox Brucellosis Hepatitis B and Hepatitis D Spotted fever rickettsiosis (e.g., Rocky Mountain spotted fever) *O Campylobacteriosis Hepatitis C Streptococcal group A infection, invasive disease Chagas infection and related disease *O Hepatitis E Streptococcal group B infection in an infant younger than 90 days of age, (American trypanosomiasis) invasive disease Chancroid HIV infection and related disease Streptococcus pneumoniae infection (pneumococcal invasive disease) Chikungunya Influenza-associated mortality in a child 1 Syphilis Chlamydia trachomatis infection Legionellosis (Legionnaires’ disease) *O Taeniasis * Cholera Leptospirosis Tetanus Coccidioidomycosis (Valley Fever) Listeriosis Toxic shock syndrome Colorado tick fever Lyme disease Trichinosis O Conjunctivitis, acute Lymphocytic choriomeningitis Tuberculosis, active disease Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease Malaria Tuberculosis latent infection in a child 5 years of age or younger (positive screening test result) *O Cryptosporidiosis -

Canine Ehrlichiosis: Update

Canine Ehrlichiosis: Update Barbara Qurollo, MS, DVM ([email protected]) Vector-Borne Disease Diagnostic Laboratory Dep. Clinical Sciences-College of Veterinary Medicine North Carolina State University Overview Ehrlichia species are tick-transmitted, obligate intracellular bacteria that can cause granulocytic or monocytic ehrlichiosis. Ehlrichia species that have been detected in the blood and tissues of clinically ill dogs in North America include Ehrlichia canis, E. chaffeenis, E. ewingii, E. muris and Panola Mountain Ehrlichia species (Table 1). Clinicopathologic abnormalities reported in dogs with ehrlichiosis vary depending on the species of Ehrlichia, strain variances and the immune or health status of the dog. The course of disease may present as subclinical, acute, chronic or even result in death (Table 1). E. canis and E. ewingii are the most prevalent and frequently described Ehrlichia infections in dogs. E. canis: Transmitted by Rhipicephalus sanguineus, E. canis is found world-wide. Within North America, the highest seroprevalence rates have been reported in the Southern U. S.2, 12 E. canis typically infects canine mononuclear cells. Canine monocytic ehrlichiosis (CME) is characterized by 3 stages: acute, subclinical and chronic. Following an incubation period of 1-3 weeks, infected dogs may remain subclinical or present with nonspecific signs including fever, lethargy, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, lameness, edema, bleeding disorders and mucopurulent ocular discharge. Less commonly reported nonspecific signs include vomiting, diarrhea, coughing and dyspnea. Bleeding disorders can include epistaxis, petechiae, ecchymoses, gingival bleeding and melena. Ocular abnormalities identified in E. canis infected dogs have included anterior uveitis, corneal opacity, retinal hemorrhage, hyphema, chorioretinal lesions and tortuous retinal vessels.8 Following an acute phase (2-4 weeks), clinical signs may resolve without treatment and the dog could remain subclinically infected indefinitely or naturally clear the pathogen. -

Ehrlichiosis Epidemiology

Ehrlichiosis Epidemiology A. Agent: Ehrlichiosis was not recognized in the U.S. until the late 1980’s and became a reportable disease in 19991,2. Ehrlichiosis is a general name used to describe several bacterial diseases in humans and animals. In the United States, ehrlichiosis can be caused by three different species of gram negative bacteria: Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Ehrlichia ewingii, and Ehrlichia muris-like (EML)1,2. B. Clinical Description: Ehrlichiosis usually presents with non-specific symptoms, including fever, headache, fatigue, and muscle aches1,2. Chills, malaise, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, confusion, and conjunctival infections can also occur1,2. Development of a skin rash is not a common feature of ehrlichiosis. About 60% of children and less than 30% of adults develop a rash1,2. The rash associated with Ehrlichia chaffeensis infection may range from maculopapular to petechial in nature, and is usually not itchy1,2. The combination of symptoms varies from person to person1,2. Severe illness can occur, including difficulty breathing or bleeding disorders1,2. Ehrlichiosis can be fatal if left untreated, and has a 1.8% case fatality rate. Immunocompromised individuals may experience a more severe clinical illness1,2. C. Vectors: The Ehrlichia bacteria are spread to humans by the bite of an infected tick. In the United States, Amblyomma americanum (lone star tick) is the primary vector of Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Ehrlichia ewingii1,2. The long star tick is often found in the southeastern and south central United States. Three states (Oklahoma, Missouri, and Arkansas) account for 30% of all reported E. chaffeensis infections1,2. A vector has not been established yet for Ehrlichia muris-like (EML), but human travel-associated cases have been identified in Minnesota and Wisconsin1,2. -

Zoonotic Diseases of Companion Animals – by Transmission

Zoonotic Diseases Direct Contact and Fomite These diseases may be spread by bites, scratches, or direct contact with of Companion animal tissues or fluids (e.g., urine, feces, saliva). Disease transmission Animals may also occur indirectly through contact with contaminated objects or surfaces (fomites), such as cages, aquaria, bowls, or bedding. Routes of Transmission • Acariasis (mange) • Lymphocytic • Pasteurellosis • Brucellosis Choriomeningitis • Plague This handout lists • Cat Scratch Disease • Melioidosis • Q Fever potential routes of • Dermatophytosis • Monkeypox • Rabies transmission of select zoonotic diseases • Glanders • Mycobacteriosis • Rat Bite Fever between animals and humans. • Influenza • Methicillin-Resistant • Salmonellosis • Leptospirosis Staphylococcus • Sporotrichosis aureus (MRSA) • Tularemia Additional routes may occur between animals. Oral These diseases can be transmitted by ingestion of food or water contaminated with a pathogen. This typically occurs from fecal contamination from unwashed hands or soil contact. • Baylisascariasis • Echinococcosis • Toxocariasis • Campylobacteriosis • Giardiasis • Toxoplasmosis • Cryptosporidiosis • Hookworm Infection • Trichuriasis • Escherichia coli • Leptospirosis • Tularemia O157:H7 • Salmonellosis • Yersiniosis Aerosol These diseases can be transmitted through the air by droplet transfer, fluids aerosolized from an animal to a person (e.g., sneezing or cough) or by aerosolized materials which are inhaled. • Bordetella Infection • Leptospirosis • Q Fever • Cryptococcosis • Melioidosis • Tularemia • Hantavirus • Plague • Influenza • Psittacosis Vector-borne These diseases are transmitted by an arthropod vector. FLEAS TICKS TRIATOMINE • Plague • Ehrlichiosis (“kissing bugs”) • Trypanosomiasis College of Veterinary Medicine MOSQUITOES • Lyme Disease Iowa State University • Rocky Mountain (Chagas disease) • West Nile Encephalitis Ames, Iowa 50011 Spotted Fever Phone: (515) 294–7189 SAND FLIES • Tularemia FAX: (515) 294–8259 • Leishmaniasis E–mail: [email protected] Web: www.cfsph.iastate.edu © 2013. -

The Prevalence of the Q-Fever Agent Coxiella Burnetii in Ticks Collected from an Animal Shelter in Southeast Georgia

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Summer 2004 The Prevalence of the Q-fever Agent Coxiella burnetii in Ticks Collected from an Animal Shelter in Southeast Georgia John H. Smoyer III Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Immunology of Infectious Disease Commons, Other Animal Sciences Commons, and the Parasitology Commons Recommended Citation Smoyer, John H. III, "The Prevalence of the Q-fever Agent Coxiella burnetii in Ticks Collected from an Animal Shelter in Southeast Georgia" (2004). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1002. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/1002 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PREVALENCE OF THE Q-FEVER AGENT COXIELLA BURNETII IN TICKS COLLECTED FROM AN ANIMAL SHELTER IN SOUTHEAST GEORGIA by JOHN H. SMOYER, III (Under the Direction of Quentin Q. Fang) ABSTRACT Q-fever is a zoonosis caused by a worldwide-distributed bacterium Coxiella burnetii . Ticks are vectors of the Q-fever agent but play a secondary role in transmission because the agent is also transmitted via aerosols. Most Q-fever studies have focused on farm animals but not ticks collected from dogs in animal shelters. In order to detect the Q-fever agent in these ticks, a nested PCR technique targeting the 16S rDNA of Coxiella burnetii was used. -

Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis - in This Issue

Volume 35, No. 5 August 2015 Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis - In this issue... Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis— Connecticut, 2011-2014 17 Connecticut, 2011-2014 Human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA), Babesiosis Surveillance—Connecticut, 2014 19 formerly known as human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, is a tick-borne disease caused by the bacterium contained information that was insufficient for case Anaplasma phagocytophilum. In Connecticut, HGA classification (e.g. positive laboratory test only, lost is transmitted to humans through the bite of an to follow-up). Of the 2,146 positive IgG titers only, infected Ixodes scapularis (deer tick or black-legged 7 (0.3%) were classified as a confirmed case after tick), the same tick that transmits Lyme disease and follow-up. During the same period, of the 483 babesiosis (1). positive PCR results received, 231 (48%) were The Connecticut Department of Public Health classified as a confirmed case after follow-up. (DPH) used the anaplasmosis National Surveillance Of the confirmed cases, date of onset of illness Case Definition (NSDC), which was established in was reported for 190 patients; 158 (84%) occurred 2009, to determine case status. The NSCD defines a during April - July. The ages of patients ranged confirmed case as a patient with clinically from 1-92 years (mean = 57.4). The age specific compatible illness characterized by acute onset of rates for confirmed cases was highest among those fever, plus one or more of the following: headache, 70-79 years of age (6.3 cases per 100,000 myalgia, anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, or population), and lowest for children < 9 years (0.3 elevated hepatic transaminases; plus 1) a fourfold cases per 100,000 population). -

Health Alert Network Advisory: Tick-Borne Diseases in Nebraska

TO: Primary care providers, infectious disease, laboratories, infection control, and public health FROM Thomas J. Safranek, M.D. Jeff Hamik, MS State Epidemiologist Vector-borne Disease Epidemiologist 402-471-2937 PHONE 402-471-1374 PHONE 402-471-3601 FAX 402-471-3601 FAX RE: TICK-BORNE DISEASES IN NEBRASKA DATE: May 6, 2020 The arrival of spring marks the beginning of another tick season. In the interest of public health and prevention, our office seeks to inform Nebraska health care providers about the known tick- borne diseases in our state. Spotted fever rickettsia (SFR) including Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) SFR is a group of related bacteria that can cause spotted fevers including RMSF. Several of these SFR have similar signs and symptoms, including fever, headache, and rash, but are often less severe than RMSF. SFR are the most commonly reported tick-borne disease in Nebraska. Our office has reported a median of 26 cases (range 16-48) with SFR over the last 5 years (2015- 2019), an increase from 10 median cases (range 5-18) reported during 2010-2014. SFR, especially RMSF NEEDS TO BE A DIAGNOSTIC CONSIDERATION IN ANY PERSON WITH A FEVER AND A HISTORY OF EXPOSURE TO ENVIRONMENTS WHERE TICKS MIGHT BE PRESENT. The skin rash is not always present when the patient first presents to a physician. RMSF is frequently overlooked or misdiagnosed, with numerous reports of serious and sometimes fatal consequences. Nebraska experienced a fatal case of confirmed RMSF in 2015 where the diagnosis was missed and treatment was delayed until the disease was well advanced. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 24/Tuesday, February 5, 2019/Proposed Rules

1678 Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 24 / Tuesday, February 5, 2019 / Proposed Rules and complete to the best of the DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS which pertains to chronic fatigue individual’s knowledge, information, AFFAIRS syndrome (CFS), and 38 CFR 4.88b, and belief, and is made in good faith. which pertains to the schedule of 38 CFR Part 4 (iii) Submission of an opt-out notice ratings for infectious diseases and immune disorders (we note that the does not constitute agreement by the RIN 2900–AQ43 proposed changes for § 4.88b exclude rights owner or the individual the schedule of ratings for nutritional submitting the opt-out notice that the Schedule for Rating Disabilities: Infectious Diseases, Immune deficiencies—diagnostic codes (DC) proposed use is in fact noncommercial. Disorders, and Nutritional Deficiencies 6313, 6314, and 6315). VA last updated The submitter may choose to comment the schedule of ratings in § 4.88b on July upon whether the rights owner agrees AGENCY: Department of Veterans Affairs. 31, 1996 (see 61 FR 39875) and updated that the proposed use is noncommercial ACTION: Proposed rule. § 4.88a on July 19, 1995 (see 60 FR use, but failure to do so does not 37012). constitute agreement that the proposed SUMMARY: The Department of Veterans VA proposes to: (1) Update the use is in fact noncommercial. Affairs (VA) proposes to amend the medical terminology and definition of section of the VA Schedule for Rating (3) Multiple rights owners. Where a certain infectious diseases and immune Disabilities (VASRD or Rating Schedule) disorders; (2) add medical conditions pre-1972 sound recording has multiple that addresses infectious diseases and rights owners, only one rights owner not currently in the Rating Schedule; (3) immune disorders. -

Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis

Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis The Diseases and Transmission • Ehrlichia and Anaplasma are related bacteria that are transmitted by ticks. These bacteria infect white blood cells in humans. • There are three main different bacteria that cause disease in humans: Ehrlichia Chaffeensis Ehrlichia ewingii Anaplasma Phagocytophilum Pathogen (formerly ehrlichichia phagocytophilia) Human moncytic Ehrlichiosis ewingii Human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA, Disease ehrlichiosis (HME) formerly HGE) Tick Amblyomma Americanum (lone start tick) Ixodes scapularis (black legged tick) Vector Location Southeast and south central US Northeast and upper Midwest US • Animal reservoirs for E. chaffeensis and E. ewingii are white-tailed deer and dogs. The reservoirs for A. phagocytophilum include cattle, deer, and rodents. You cannot get the diseases directly from animals. • The diseases are not spread between humans other than through blood transfusions. • Maryland is home to both the lone star tick and the black-legged tick. Symptoms and Treatment Disease Clinical Features • Symptoms appear 1 to 2 weeks after a tick bite. • Symptoms include fever, headache, muscle aches, nausea, vomiting, HME, diarrhea, confusion, chills and malaise. Ehrlichiosis ewingii • Conjunctival infection (red eyes) • Development of a rash may occur in up to 60% of children and <30% of adults. This may be confused with Rocky Mountain spotted fever. • Symptoms appear 1 to 2 weeks after a tick bite. • Symptoms include fever, headache, cough, nausea/abdominal pain, chills, HGA malaise, confusion and muscle aches. • Rash is rare • Most infections occur when tick activity is highest, in late spring and summer. • If left untreated, HME and HGA may be severe. • Co-infection with more than one tickborne disease is possible.