The Dublin Lockout, 1913 - John Dorney

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Failure of an Irish Political Party

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DCU Online Research Access Service 1 Journalism in Ireland: The Evolution of a Discipline Mark O’Brien While journalism in Ireland had a long gestation, the issues that today’s journalists grapple with are very much the same that their predecessors had to deal with. The pressures of deadlines and news gathering, the reliability and protection of sources, dealing with patronage and pressure from the State, advertisers and prominent personalities, and the fear of libel and State regulation were just as much a part of early journalism as they are today. What distinguished early journalism was the intermittent nature of publication and the rapidity with which newspaper titles appeared and disappeared. The Irish press had a faltering start but by the early 1800s some of the defining characteristics of contemporary journalism – specific skill sets, shared professional norms and professional solidarity – had emerged. In his pioneering work on the history of Irish newspapers, Robert Munter noted that, although the first newspaper printed in Ireland, The Irish Monthly Mercury (which carried accounts of Oliver Cromwell’s campaign in Ireland) appeared in December 1649 it was not until February 1659 that the first Irish newspaper appeared. An Account of the Chief Occurrences of Ireland, Together with some Particulars from England had a regular publication schedule (it was a weekly that published at least five editions), appeared under a constant name and was aimed at an Irish, rather than a British, readership. It, in turn, was followed in January 1663 by Mercurius Hibernicus, which carried such innovations as issue numbers and advertising. -

The Banshee's Kiss: Conciliation, Class and Conflict in Cork and The

The Banshee’s Kiss: Conciliation, Class and Conflict in Cork and the All for Ireland League. Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Patrick Joseph Murphy. August 2019 1 The Banshee’s Kiss: Conciliation, Class and Conflict in Cork and the All for Ireland League. ABSTRACT Historians have frequently portrayed constitutional nationalism as being homogeneous - ‘the Home Rule movement’- after the reunification of the Irish parliamentary party in 1900. Yet there were elements of nationalist heterodoxy all over the country, but it was only in Cork where dissent took an organised form in the only formal breakaway from the Irish party when the All for Ireland League (A.F.I.L.) was launched in 1910. The AFIL took eight of the nine parliamentary seats in Cork and gained control of local government in the city and county the following year. Existing historical accounts do not adequately explain why support for the Home Rule movement collapsed in Cork, but also why the AFIL flourished there but failed, despite the aspiration of its name, to expand beyond its regional base. The AFIL is chiefly remembered for its visionary policy of conciliation with unionists following the Damascene conversion of its leader William O’Brien, transformed from the enemy of the landed classes to an apostle of a new kind of bi- confessional politics. This would, he claimed, end the ‘Banshee’s Kiss’, a cycle of conflict in which each new generation attempts to achieve Irish freedom. However, conciliation was a policy which was unpopular with both nationalists and unionists and O’Brien therefore needed to develop an electoral base by other means with more popular policies. -

Contents PROOF

PROOF Contents Notes on the Contributors vii Introduction 1 1 The Men of Property: Politics and the Languages of Class in the 1790s 7 Jim Smyth 2 William Thompson, Class and His Irish Context, 1775–1833 21 Fintan Lane 3 The Rise of the Catholic Middle Class: O’Connellites in County Longford, 1820–50 48 Fergus O’Ferrall 4 ‘Carrying the War into the Walks of Commerce’: Exclusive Dealing and the Southern Protestant Middle Class during the Catholic Emancipation Campaign 65 Jacqueline Hill 5 The Decline of Duelling and the Emergence of the Middle Class in Ireland 89 James Kelly 6 ‘You’d be disgraced!’ Middle-Class Women and Respectability in Post-Famine Ireland 107 Maura Cronin 7 Middle-Class Attitudes to Poverty and Welfare in Post-Famine Ireland 130 Virginia Crossman 8 The Industrial Elite in Ireland from the Industrial Revolution to the First World War 148 Andy Bielenberg v October 9, 2009 17:15 MAC/PSMC Page-v 9780230_008267_01_prex PROOF vi Contents 9 ‘Another Class’? Women’s Higher Education in Ireland, 1870–1909 176 Senia Pašeta 10 Class, Nation, Gender and Self: Katharine Tynan and the Construction of Political Identities, 1880–1930 194 Aurelia L. S. Annat 11 Leadership, the Middle Classes and Ulster Unionism since the Late-Nineteenth Century 212 N. C. Fleming 12 William Martin Murphy, the Irish Independent and Middle-Class Politics, 1905–19 230 Patrick Maume 13 Planning and Philanthropy: Travellers and Class Boundaries in Urban Ireland, 1930–75 249 Aoife Bhreatnach 14 ‘The Stupid Propaganda of the Calamity Mongers’?: The Middle Class and Irish Politics, 1945–97 271 Diarmaid Ferriter Index 289 October 9, 2009 17:15 MAC/PSMC Page-vi 9780230_008267_01_prex PROOF 1 The Men of Property: Politics and the Languages of Class in the 1790s Jim Smyth Political rhetoric in Ireland in the 1790s – the sharply conflicting vocabularies of reform and disaffection, liberty, innovation. -

The Capuchin Annual and the Irish Capuchin Publications Office

1 Irish Capuchin Archives Descriptive List Papers of The Capuchin Annual and the Irish Capuchin Publications Office Collection Code: IE/CA/CP A collection of records relating to The Capuchin Annual (1930-77) and The Father Mathew Record later Eirigh (1908-73) published by the Irish Capuchin Publications Office Compiled by Dr. Brian Kirby, MA, PhD. Provincial Archivist July 2019 No portion of this descriptive list may be reproduced without the written consent of the Provincial Archivist, Order of Friars Minor Capuchin, Ireland, Capuchin Friary, Church Street, Dublin 7. 2 Table of Contents Identity Statement.......................................................................................................................................... 5 Context................................................................................................................................................................ 5 History ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Archival History ................................................................................................................................. 8 Content and Structure ................................................................................................................................... 8 Scope and content ............................................................................................................................. 8 System of arrangement .................................................................................................................... -

St. Finbarr's Catholic Church, Bantry

Bantry Historical and Archaeological Society Journal article, Nov.-Dec. 2017 3,000-7,000 words inc. footnotes, up to 6-7 images St. Finbarr’s Catholic Church, Bantry: a history1 Richard J. Butler 11 Dec. 2017 St. Finbarr’s Catholic Church in Bantry has a long and rich history, and is widely regarded as one of the most important buildings in the town and surrounding area. It has recently undergone an extensive refurbishment, including the complete reconstruction of its historic pipe organ, the installation of a new floor and the repointing of much of the exterior stonework. Within the next decade will be the bicentenary of its construction. The purpose of this article is to offer a history of the church over the past two centuries, with particular focus on developments in the twentieth century. I will also comment on the church’s earlier history, about which there is some degree of uncertainty. The most comprehensive history of St. Finbarr’s to date is an article by one of Bantry’s most distinguished local historians, Donal Fitzgerald, a copy of which is kept in Bantry Museum. 2 In writing this history I am greatly indebted to his local knowledge and years of painstaking research. There are also some shorter histories – for example in the recent Bantry Historic Town Map, and in the tourist information boards placed around the town.3 There is also in preparation, and due for publication hopefully in 2018 or 2019, the Buildings of Ireland volume for Cork, which will include the most comprehensive architectural history to date of all of Bantry’s important buildings.4 The early nineteenth century – especially the years before and after Catholic Emancipation (1829) – was a rich period in the building of Catholic churches in Ireland. -

NUI MAYNOOTH Imperial Precedents in the Home Rule Debates, 1867

NUI MAYNOOTH Ollscoil na hÉlreann MA Nuad Imperial precedents in the Home Rule Debates, 1867-1914 by Conor Neville THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF MLITT DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH Supervisor of Research: Prof. Jacqueline Hill February, 2011 Imperial precedents in the Home Rule Debates, 1867-1914 by Conor Neville 2011 THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF MLITT DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH Contents Acknowledgements iii Abbreviations iv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Taking their cues from 1867: Isaac Butt and Home Rule in the 1870s 16 Chapter 2: Tailoring their arguments: The Home Rule party 1885-1893 60 Chapter 3: The Redmondite era: Colonial analogies during the Home Rule crisis 110 Conclusion 151 Bibliography 160 ii Acknowledgements I wish to thank both the staff and students of the NUI Maynooth History department. I would like, in particular, to record my gratitude to my supervisor Prof. Jacqueline Hill for her wise advice and her careful and forensic eye for detail at all times. I also wish to thank the courteous staff in the libraries which I frequented in NUI Maynooth, Trinity College Dublin, University College Dublin, the National Libraiy of Ireland, the National Archives, and the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland. I want to acknowledge in particular the help of Dr. Colin Reid, who alerted me to the especially revelatory Irish Press Agency pamphlets in the National Library of Ireland. Conor Neville, 27 Jan. 2011 iil Abbreviations A. F. I. L. All For Ireland League B. N. A. British North America F. J. Freeman’s Journal H. -

Private Sources at the National Archives

Private Sources at the National Archives Small Private Accessions 1972–1997 999/1–999/850 1 The attached finding-aid lists all those small collections received from private and institutional donors between the years 1972 and 1997. The accessioned records are of a miscellaneous nature covering testamentary collections, National School records, estate collections, private correspondence and much more. The accessioned records may range from one single item to a collection of many tens of documents. All are worthy of interest. The prefix 999 ceased to be used in 1997 and all accessions – whether large or small – are now given the relevant annual prefix. It is hoped that all users of this finding-aid will find something of interest in it. Paper print-outs of this finding-aid are to be found on the public shelves in the Niall McCarthy Reading Room of the National Archives. The records themselves are easily accessible. 2 999/1 DONATED 30 Nov. 1972 Dec. 1775 An alphabetical book or list of electors in the Queen’s County. 3 999/2 COPIED FROM A TEMPORARY DEPOSIT 6 Dec. 1972 19 century Three deeds Affecting the foundation of the Loreto Order of Nuns in Ireland. 4 999/3 DONATED 10 May 1973 Photocopies made in the Archivio del Ministerio de Estado, Spain Documents relating to the Wall family in Spain Particularly Santiago Wall, Conde de Armildez de Toledo died c. 1860 Son of General Santiago Wall, died 1835 Son of Edward Wall, died 1795 who left Carlow, 1793 5 999/4 DONATED 18 Jan. 1973 Vaughan Wills Photocopies of P.R.O.I. -

1913 Lockout When Tram Drivers Were Forbidden to Join the Union, and Were Forced to Sign Forms Promising They Wouldn’T Join

1913 LOCKOUT -1- Some hard stuff explained! Lockout: A lockout happens when the owner of a business has a disagreement with the company's employees, resulting in the business being locked up. As a result, the workers can't do their day’s work and don't get paid by their employer. Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP): In 1913 there were two police forces in Ireland. The DMP (Dublin Metropolitan Police) were located, as you would expect, in Dublin. The rest of the country was policed by the RIC (the Royal Irish Constabulary). The difference between the two forces is important – the Dublin police, like today’s Garda, were not armed. The RIC, throughout the rest of Ireland, were allowed to carry handguns and rifles. Money: In 1913, and all the way up until 1971, money was more complicated that it is today. Back then, there were Pounds, Shillings and Pence (Pennies). The symbol for pounds was “£”, for shillings, “s” and pence was “d” Today, we all know there are 100 cents in a Euro. Back then, there were 240 pence in a pound, and 12 pence in a shilling! So a label in a shop would read “£1-2-6d” which was “One pound, two shillings and sixpence”. To calculate the number of pennies: 240 + 12 + 12 + 6 = 270 pence. ITGWU (Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union): A union (or Trade Union) is a collection of people who come together to make sure their working conditions and pay are protected. The ITGWU was formed in 1909 by Jim Larkin and was at the centre of the events of the 1913 lockout when tram drivers were forbidden to join the union, and were forced to sign forms promising they wouldn’t join. -

United Irish League, and M.P

From: Redmond Enterprise Ronnie Redmond To: FOMC-Regs-Comments Subject: Emailing redmond.pdf Date: Wednesday, October 14, 2020 2:44:55 PM Attachments: redmond.pdf NONCONFIDENTIAL // EXTERNAL I want this cause im a Redmond and i want to purchase all undeveloped and the government buildings the Queen of England even if i have to use PROBATES LAW RONNIE JAMES REDMOND Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 118 PAPERS OF JOHN REDMOND MSS 3,667; 9,025-9,033; 15,164-15,280; 15,519-15,521; 15,523-15,524; 22,183- 22,189; 18,290-18,292 (Accessions 1154 and 2897) A collection of the correspondence and political papers of John Redmond (1856-1918). Compiled by Dr Brian Kirby holder of the Studentship in Irish History provided by the National Library of Ireland in association with the National Committee for History. 2005-2006. The Redmond Papers:...........................................................................................5 I Introduction..........................................................................................................5 I.i Scope and content: .....................................................................................................................5 I.ii Biographical history: .................................................................................................................5 I.iii Provenance and extent: .........................................................................................................7 I.iv Arrangement and structure: ..................................................................................................8 -

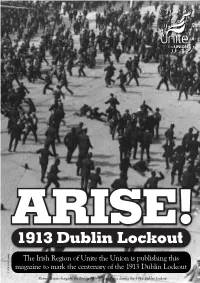

The Irish Region of Unite the Union Is Publishing This Magazine to Mark

5895-Irish_PolConf_Summer13_Final:Layout 1 19/06/2013 09:13 Page 1 The Irish Region of Unite the Union is publishing this magazine to mark the centenary of the 1913 Dublin Lockout © RTÉ Stills Library Picture: Baton charge by the Dublin Metropolitan Police during the 1913 Dublin Lockout 5895-Irish_PolConf_Summer13_Final:Layout 1 19/06/2013 09:13 Page 2 Page 2 June 2013 Larkininism and internationalism This is an edited version of a lecture delivered by Unite General Secretary Len McCluskey to a meeting organised by Unite with the support of the Dublin Council of Trade Unions and Dublin Community Television. The event took place in Dublin on May 29th 2013 A crowd awaits the arrival of the first food ship from England, 28 September 1913 (Irish Life magazine). Contents Page2: Len McCluskey – Larkinismandinternationalism Page7: Jimmy Kelly – 1913–2013:Forgingalliancesofthediscontented Page9: Theresa Moriarty – Womenattheheartofthestruggle Page11: Padraig Yeates – AveryBritishstrike 5895-Irish_PolConf_Summer13_Final:Layout 1 19/06/2013 09:13 Page 3 June 2013 Page 3 It is a privilege for me to have this opportunity workers,andgovernmentsunableorunwillingto IamproudthatUniteisleadingbyexample.Weare to speak about a man – from my own city – bringaboutthereformpeoplesodesperatelyneed. committedtobuildinganewsenseofoptimismfor who I consider a personal hero. ourmovement,whetherthatisathomethroughour Acrosstheworld,multilateralinstitutionsandthe communitymembershipbringingtheunemployed Iwanttotouchonanumberofthemesrelatingto agreementsthatemanatefromthemarelittle -

Lockout Chronology 1913-14

Lockout Chronology 1913-14 Historical background The Great Dublin Lockout was the first major urban based conflict in modern Ireland. For a time it overshadowed the Home Rule crisis. It evoked strong emotions on all sides and constituted a major challenge to the conservative middle class Catholic consensus which dominated nationalist politics. It did not emerge from a vacuum. Several attempts had been made since the 1880s to introduce the ‘new unionism’ to Ireland, aimed at organising unskilled and semi-skilled workers who had traditionally been excluded from the predominantly British based craft unions. It was 1907 when Jim Larkin arrived in Ireland as an organiser for the National Union of Dock Labourers, whose general secretary James Sexton was himself a former Fenian. However the Liverpool-Irishman’s fiery brand of trade unionism, characterised by militant industrial action combined with a syndicalist political outlook, was more than the NUDL could tolerate. After spectacular initial success in Belfast, where he succeeded briefly in uniting workers in a demand for better pay and conditions, Larkin proceeded to organise NUDL branches in most of Ireland’s ports. It was his handling of a Cork docks strike in 1908 that provided an opening for his dismissal. Sexton accused him of unauthorised use of union funds to issue strike pay before the NUDL executive had sanctioned it. Larkin was imprisoned for embezzlement in a case where Sexton was the main witness for the prosecution. Far from destroying Larkin’s reputation, his imprisonment made him the hero of a generation of young Irish socialists who campaigned successfully for his release. -

Murphy, William Martin by Patrick Maume

Murphy, William Martin by Patrick Maume Murphy, William Martin (1845–1919), businessman, was born on 6 January 1845 at Derrymihan, near Castletownbere, Co. Cork, son of Denis William Murphy, building contractor, and his wife, Mary Anne (née Martin). His solitary and austere personality was influenced by his status as an only child and his mother's death when he was four. He was educated at Bantry national school and Belvedere College in Dublin. He worked in the offices of the Irish Builder and the Nation, whose proprietor, A. M. Sullivan (qv), was a Bantry man and family friend. This drew Murphy into the ‘Bantry band’, the group formed round the family connection between Sullivan and T. M. Healy (qv), which dominated the conservative wing of late-Victorian Irish nationalism. In 1863 Murphy inherited the family business on the death of his father. In 1867 he moved to Cork, where in 1870 he married Mary Julia Lombard, daughter of a prominent Cork businessman, James Fitzgerald Lombard (qv). They had five sons and three daughters, whose marriages (notably with the Chance family) strengthened Murphy's political and business alliances. His success was based on building light railways in the south and west of Ireland; he also became involved in running these railways, sat on several boards, and facilitated the merger that created the Great Southern and Western Railway. On the back of his success in business, Murphy moved to Dublin in 1875, buying Dartry Hall, Upper Rathmines, his principal residence for the rest of his life. He prided himself on not moving to London, as many successful Irish businessmen did at that time.